A Short History of at Penn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

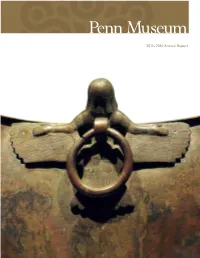

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3d5n99tn No online items Guide to the A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972 Processed by Xiuzhi Zhou Jane Bassett Lauren Lassleben Claora Styron; machine-readable finding aid created by James Lake The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History --History, University of California --History, UC BerkeleyGeographical (by Place) --University of California --University of California BerkeleySocial Sciences --AnthropologySocial Sciences --Area and Interdisciplinary Studies --Native American Studies Guide to the A. L. Kroeber BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 1 Papers, 1869-1972 Guide to the A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972 Collection number: BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Xiuzhi Zhou Jane Bassett Lauren Lassleben Claora Styron Date Completed: 1997 Encoded by: James Lake © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: A. L. Kroeber Papers, Date (inclusive): 1869-1972 Collection Number: BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 Creator: Kroeber, A. L. (Alfred Louis), 1876-1960 Extent: Originals: 40 boxes, 21 cartons, 14 volumes, 9 oversize folders (circa 45 linear feet)Copies: 187 microfilm reels: negative (Rich. -

Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: a Biographical and Contextual View Karen L

Andean Past Volume 7 Article 14 2005 Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View Karen L. Mohr Chavez deceased Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mohr Chavez, Karen L. (2005) "Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View," Andean Past: Vol. 7 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFRED KIDDER II IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CONTEXTUAL VIEW KAREN L. MOHR CHÁVEZ late of Central Michigan University (died August 25, 2001) Dedicated with love to my parents, Clifford F. L. Mohr and Grace R. Mohr, and to my mother-in-law, Martha Farfán de Chávez, and to the memory of my father-in-law, Manuel Chávez Ballón. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SERGIO J. CHÁVEZ1 corroborate crucial information with Karen’s notes and Kidder’s archive. Karen’s initial motivation to write this biography stemmed from the fact that she was one of Alfred INTRODUCTION Kidder II’s closest students at the University of Pennsylvania. He served as her main M.A. thesis This article is a biography of archaeologist Alfred and Ph.D. dissertation advisor and provided all Kidder II (1911-1984; Figure 1), a prominent necessary assistance, support, and guidance. -

Franz Boas's Legacy of “Useful Knowledge”: the APS Archives And

Franz Boas’s Legacy of “Useful Knowledge”: The APS Archives and the Future of Americanist Anthropology1 REGNA DARNELL Distinguished University Professor of Anthropology University of Western Ontario t is a pleasure and privilege, though also somewhat intimidating, to address the assembled membership of the American Philosophical ISociety. Like the august founders under whose portraits we assemble, Members come to hear their peers share the results of their inquiries across the full range of the sciences and arenas of public affairs to which they have contributed “useful knowledge.” Prior to the profes- sionalization of science in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the boundaries between disciplines were far less significant than they are today. Those who were not experts in particular topics could rest assured that their peers were capable of assessing both the state of knowledge in each other’s fields and the implications for society. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington were all polymaths, covering what we now separate into several kinds of science, humanities, and social science in ways that crosscut one another and illustrate the permeability of disciplinary boundaries. The study of the American Indian is a piece of that multidisciplinary heri- tage that constituted the APS and continues to characterize its public persona. The Founding Members of the Society all had direct and seminal experience with the Indians and with the conflict between their traditional ways of life and the infringing world of settler colonialism. On the one hand, they felt justified in exploiting Native resources, as surveyors, treaty negotiators, and land speculators. On the other hand, the Indians represented the uniqueness of the Americas, of the New World that defined itself apart from the decadence of old Europe. -

A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 3-14-2018 A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space Katelyn Elizabeth Braymer-Hayes Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Braymer-Hayes, Katelyn Elizabeth, "A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre- Contact Gendered Use of Space" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4357. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6250 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space by Katelyn Elizabeth Braymer-Hayes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Shelby L. Anderson, Chair Virginia L. Butler Douglas C. Wilson Portland State University 2018 Abstract Activities and production among ethnographic Arctic peoples were primarily divided by gender. This gendered division of labor also extended to a spatial segregated pattern of the household in some Arctic cultures. Other cultures had a more gender-integrated spatial pattern of the household. There have been very few archaeological studies of gender in the Arctic, and even fewer studies of gendered use of space. In this thesis, I evaluated the existence of this gendered use of space in pre-contact Northwest Alaska. -

The Cinchona Program (1940-1945): Science and Imperialism in the Exploitation of a Medicinal Plant

The Cinchona Program (1940-1945): science and imperialism in the exploitation of a medicinal plant Nicolás Cuvi (*) (*) Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO-Ecuador; Centre d’Història de la Ciència, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [email protected] Dynamis Fecha de recepción: 25 de enero de 2010 [0211-9536] 2011; 31 (1): 183-206 Fecha de aceptación: 27 de julio de 2010 SUMARIO: 1.—Introduction. 2.—Cinchona and its alkaloids. 3.—The War and the need for raw materials. 4.—The quest for Cinchona in the Andes. 5.—Extraction and sale of Cinchona. 6.—Nur- series, plantations and alkaloids factories. 7.—The end of the Cinchona Program. 8.—Epilogue. ABSTRACT: During World War II, the United States implemented programs to exploit hundreds of raw materials in Latin America, many of them botanical. This required the participation of the country’s scientific community and marked the beginning of intervention in Latin Ame- rican countries characterized by the active participation of the United States in negotiations (and not only by private firms supported by the United States). Many federal institutions and companies were created, others were adapted, and universities, research centers and pharma- ceutical companies were contracted. The programs undertaken by this coalition of institutions served to build and consolidate the dependence of Latin American countries on United States technology, to focus their economies on the extraction and development of resources that the United States could not obtain at home (known as «complementary») and to impede the development of competition. Latin American republics had been historically dependant on raw material exports (minerals and plants). -

De Laguna 1960:102

78 UNIVERSITY ANTHROPOLOGY: EARLY1DEPARTMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES John F. Freeman Paper read before the Kroeber Anthropological Society April 25, 1964, Berkeley, California I. The Conventional View Unlike other social sciences, anthropology prides itself on its youth, seeking its paternity in Morgan, Tylor, Broca, and Ratzel, its childhood in the museum and its maturity in the university. While the decades after 1850 do indeed suggest that a hasty marriage took place between Ethnology, or the study of the races of mankind conceived as divinely created, and Anthropology, or the study of man as part of the zoological world; the marriage only symbol- ized the joining of a few of the tendencies in anthropology and took place much too late to give the child an honest name. When George Grant MacCurdy claimed in 1899 that "Anthropology has matured late," he was in fact only echoing the sentiments of the founders of the Anthropological Societies of Paris (Paul Broca) and London (James Hunt), who in fostering the very name, anthropology, were urging that a science of man depended upon prior develop- ments of other sciences. MacCurdy stated it In evolutionary terms as "man is last and highest in the geological succession, so the science of man is the last and highest branch of human knowledge'" (MacCurdy 1899:917). Several disciples of Franz Boas have further shortened the history of American anthropology, arguing that about 1900 anthropology underwent a major conversion. Before that date, Frederica de Laguna tells us, "anthropologists [were] serious-minded amateurs or professionals in other disciplines who de- lighted in communicating-across the boundaries of the several natural sci- ences and the humanities, [because] museums, not universities, were the cen- ters of anthropological activities, sponsoring field work, research and publication, and making the major contributions to the education of profes- sional anthropologists, as well as serving the general public" (de Laguna 1960:91, 101). -

Art, Artifact, Anthropology: the Display and Interpretation of Native American Material Culture in North American Museums Laura Browarny Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) 2010 Art, Artifact, Anthropology: The Display and Interpretation of Native American Material Culture in North American Museums Laura Browarny Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Browarny, Laura, "Art, Artifact, Anthropology: The Display and Interpretation of Native American Material Culture in North American Museums" (2010). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 736. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/736 Art, Artifact, Anthropology: The Display and Interpretation of Native American Material Culture in North American Museums By Laura Browarny Advised by Dr. Charlotte Nichols, Ph.D Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Museum Professions Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ August 2010 Abstract Native American material culture appears in a wide variety of museum contexts across the United States. Historically, these artifacts have been misinterpreted, misrepresented, and ultimately disrespected. Today, many museums are making strides to reorganize and rejuvenate their American lndian collections, and these attempts are manifested differently in each museum genre. In this paper, I discuss the history of the display of lndian objects in different types of museums, the ways in which these methods of display have evolved over time, and how these early conventions still influence current museum practices. I analyze the theory and works of Franz Boas and relate his early methods to modern museum practices. Finally, I present a series of case studies on various museums that actively collect and exhibit lndian cultural material, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The American and Field Museums of Natural History, the Museum of lndian Arts and Culture, and the Navajo Nation Museum. -

Reminiscences of Anthropological Currents in America Half a Century Ago

UC Berkeley Anthropology Faculty Publications Title Reminiscences of Anthropological Currents in America Half a Century Ago Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2vk1833m Journal American Anthropologist, 58(6) Author Lowie, Robert H. Publication Date 1956-12-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Reminiscences of Anthropological Currents in America Half a Century Ago ROBERT H. LOWIE University of California HE Editor of the AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST has asked me to offer "some T discussion and analysis of the intellectual ferment, the various ideas and interests, and the important factual discoveries in their relationship to these ideas, that were current during the period of your early years as an anthropolo gist." In responding I shall have to go far afield. The task suggested implies nevertheless two noteworthy restrictions. Factual discoveries are irrelevant (except as they influenced ideas), as is administrative promotion of scientific interests. Accordingly, though sharing Sapir's judgment that as a field worker J. O. Dorsey was "ahead of his age," I must ignore him for present purposes. Again, there will be only brief references to Frederic Ward Putnam (1839-1915) and to Frederic Webb Hodge (1864-1956); as to Powell and McGee, only their thinking demands extended notice. It is well to recall that in 1904, when I began graduate work, only Columbia, Harvard, and California had full-fledged academic departments of anthropol ogy, but the Field Museum, a descendant of the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, had been fostering research, as had the Bureau of American Ethnology and the United States National Museum. -

January 1968

Luce, Harris Named Faculty, Administration Give University Professors Two faculty members were named $3 Million to University Professors by the Board of Capital Campaign Trustees during their meeting last A total of 1,630 faculty and staff the country couldn't ask for a more month. They are Dr. Robert Duncan members of the University of Pennsyl- heartwarming vote of encouragement." Luce, professor of psychology, and Dr. vania have given $3,288,682 anony- It is hoped that by the May Trustees Zellig Harris, professor of linguistics. mously to its Development Program, meeting, at least 75 percent of the faculty University professorships were estab- Wilfred D. Gillen, chairman of the and staff will have participated. lished at Pennsylvania in 1961 to honor University's trustees, announced in Leading the appeal among the aca- those faculty members who are particu- December. demic faculties is Dr. George 'W. Taylor, larly distinguished in scholarship and It is believed that this is the larg- Harnwell Professor of Industry and whose contributions to knowledge have est amount ever contributed by any noted labor mediator; among the medical been made in more than one discipline, faculty and administration to a campaign faculties, Dr. Richard H. Chamberlain, rather than in a narrow field of speciali- of this kind. Over 50 percent have con- chairman of the Radiology Department zation. Dr. Luce and Dr. Harris are the tributed to the campaign. in the School of Medicine; and among eighth and ninth scholars to be named Gillen said the faculty-staff gifts had the administrative staff, Dr. Donald S. -

Body of Pennsylvania, the Atwater-Kent Museum, the Museum

REVIEWS 239 Philadelphia and the Development of papers offers an important and coherent account Americanist Archaeology of one major American city’s contributions to Don D. Fowler and David R. Wilcox the intellectual development of archaeology as a learned profession in the Americas. (editors) Curtis M. Hinsley’s sweeping and finely University of Alabama Press, crafted contribution leads off the volume with Tuscaloosa, 2003. xx+246 pp., 13 an insightful analysis of Philadelphia’s late-19th illus. $65.00 cloth. century social milieu that set the city apart from Boston, New York, and other eastern cities as Being a native Philadelphian, I had the good a center of intellectual foment. Hinsley sagely fortune early on to come under the infl uence observes that it was Philadelphia’s late-19th- of the cultural opportunities offered by the city. century atmosphere of “business aristocracy” Many of Philadelphia’s venerable institutions and genteel wealth that ultimately created the were routinely on my family’s list of places climate that allowed for the leaders of the to visit when going “into town,” including the city’s institutions to become some of the coun- Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the try’s prime players in the developing fi eld of Philadelphia Academy of Music, the Franklin archaeology. Presaging some of the later chap- Institute, the Philadelphia Art Museum, and the ters in the volume, Hinsley identifi es these key University Museum of the University of Penn- players as Daniel G. Brinton, Sara Stevenson, sylvania. In my career, I soon became aware of Stewart Culin, Charles C. -

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES in the HISTORY of ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O. Murray Cultural Negotiations The Role of Women in the Founding of Americanist Archaeology DAVID L. BROWMAN University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London © 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Browman, David L. Cultural negotiations: the role of women in the founding of Americanist archaeology / David L. Browman. pages cm.— (Critical studies in the history of anthropology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8032-4381-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Women archaeologists—Biography. 2. Archaeology—United States—History. 3. Women archaeologists—History. 4. Archaeologists—Biography. I. Title. CC110.B76 2013 930.1092'2—dc23 2012049313 Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington. Designed by Nathan Putens. Contents Series Editors’ Introduction vii Introduction 1 1. Women of the Period 1865 to 1900 35 2. New Directions in the Period 1900 to 1920 73 3. Women Entering the Field during the “Roaring Twenties” 95 4. Women Entering Archaeology, 1930 to 1940 149 Concluding Remarks 251 References 277 Index 325 Series Editors’ Introduction REGNA DARNELL AND STEPHEN O. MURRAY David Browman has produced an invaluable reference work for prac- titioners of contemporary Americanist archaeology who are interested in documenting the largely unrecognized contribution of generations of women to its development. Meticulous examination of the archaeo- logical literature, especially footnotes and acknowledgments, and the archival records of major universities, museums, field school programs, expeditions, and general anthropological archives reveals a complex story of marginalization and professional invisibility, albeit one that will be surprising neither to feminist scholars nor to female archaeologists.