University of Oklahoma Graduate College Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

THE GIVERS: EAU CLAIRE PHILANTHROPISTS in the CONTEXT of AMERICAN TRENDS Neil D. Bonham History 489 Professor James Oberly Marc

THE GIVERS: EAU CLAIRE PHILANTHROPISTS IN THE CONTEXT OF AMERICAN TRENDS Neil D. Bonham History 489 Professor James Oberly March 25, 2009 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author 1 Contents ABSTRACT 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The Coors Family 5 Philanthropy 8 Andrew Carnegie’s Beliefs 14 Rockefeller Ways 21 The Inheritance Tax 23 Givers of Eau Claire 27 CONCLUSION 36 WORKS CITED 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 39 2 Abstract “The Givers: Philanthropy in Eau Claire.” Neil D. Bonham Philanthropy is an important facet in communities around the world. It is a practice that provides many important services that may not exist if it were not for the generosity of others who donate their time and money. This paper will be focusing exclusively on monetary forms of philanthropy. Philanthropy exists in many different forms and is motivated in many different ways. It comes from the wealthiest of individuals to the most financially challenged of people. This paper explores what philanthropy is, the different types of philanthropy, and motivations for philanthropy. It will cover information about some of the most famous of givers. It then will make a local connection by talking about the Philanthropists for Eau Claire, their lives, and the benefits received by their donations. 3 Introduction The City of Eau Claire is filled with buildings and places dedicated to individuals. Those names often are put in honor of those who made their existence possible. Some examples are Carson Park, Randall Park, and L.E. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

BRIDGING THE GAP: DREW HAYDEN TAYLOR, NATIVE CANADIAN PLAYWRIGHT IN HIS TIMES Dale J. Young A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Committee: Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Dr. Lynda Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Jonathan Chambers Bradford Clark © 2005 Dale Joseph Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor In his relatively short career, Drew Hayden Taylor has amassed a significant level of popular and critical success, becoming the most widely produced Native playwright in the world. Despite nearly twenty years of successful works for the theatre, little extended academic discussion has emerged to contextualize Taylor’s work and career. This dissertation addresses this gap by focusing on Drew Hayden Taylor as a writer whose theatrical work strives to bridge the distance between Natives and Non-Natives. Taylor does so in part by humorously demystifying the perceptions of Native people. Taylor’s approaches to humor and demystification reflect his own approaches to cultural identity and his expressions of that identity. Initially this dissertation will focus briefly upon historical elements which served to silence Native peoples while initiating and enforcing the gap of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. Following this discussion, this dissertation examines significant moments which have shaped the re-emergence of the Native voice and encouraged the formation of the Contemporary Native Theatre in Canada. Finally, this dissertation will analyze Taylor’s methodology of humorous demystification of Native peoples and stories on the stage. -

Honga : the Leader, V. 02, No. 08 American Indian Center of Omaha, Inc

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Honga: the leader Digitized Series 8-1-1979 Honga : the leader, v. 02, no. 08 American Indian Center of Omaha, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/honga Recommended Citation of Omaha, Inc., American Indian Center, "Honga : the leader, v. 02, no. 08" (1979). Honga: the leader. 19. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/honga/19 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Series at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honga: the leader by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - I n~l.D PREMIERE" "FOOTPRINTS IN BLOOD" "NJG 31 - SEP 3, 1979n "~ CIVIC AUDIT0Rllt1" ' The Leader' ~ * * * * * VOL II - NO, ~ N-EP.ICAN INDIAN CENTER OF C1-WiA, INC. -- AUGUST 1979 * *;. • • * * * FOOTPRltITS IN BLOOD ·"My hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. ~ If you pierce your hand, you also feel ~ , pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours • • I am a man. The same God made us both." --Standing Bear One of the most important court decisions in American history was made in Om~ha 100 years ago. The trial of Standing Bear and the Ponca people is a powerful episode in the ~truggle for human rights. The American Indian Center of Omaha, Inc., will sponsor and present the penniere produ~ tion of FOOTPRINTS IN BLOOD, the new play based on the life of Standing Bear, at the Omaha Civic Auditorium August 31 - September 3, 1979, as a highlight of "Septemberfest." (This edition of the HONGA is dedicated in· memory of Chief Standing Bear of the Poncas.) Written and dramatizE!d 'by Christopher Sergel 1 playwright for "Black E~k ';Speaks'I snd ''.To Kil 1. -

•Œmake-Believe White-Menâ•Š and the Omaha Land Allotments of 1871-1900

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences Great Plains Studies, Center for August 1994 “Make-Believe White-Men” and the Omaha Land Allotments of 1871-1900 Mark J. Awakuni-Swetland University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Awakuni-Swetland, Mark J., "“Make-Believe White-Men” and the Omaha Land Allotments of 1871-1900" (1994). Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 232. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch/232 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Great Plains Research 4 (August 1994) 201-236 © Copyright by the Center for Great Plains Studies "MAKE-BELIEVE WHITE-MEN" AND THE OMAHA LAND ALLOTMENTS OF 1871-1900 Mark J. Swetland Center for Great Plains Studies and Department ofAnthropology University ofNebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588-0317 Abstract. The (Dawes) General Allotment Act of1887 was meant to fulfill the United States Government policy ofallotting individual parcels of Indian reservation lands in an effort to break up communal societies,Jorcing tribes to move towards the white man's ideal of civilized culture. Three decades earlier, Article 6 ofthe Treaty of1854 allowed for the survey and allotting of the Omaha's northeastern Nebraska reservation, placing the Omaha Nation at the leading edge offederal policy a generation before the Dawes Act. -

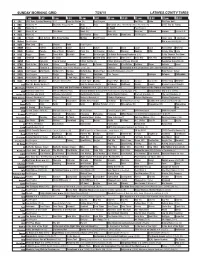

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Stable Isotopic Insights Into the Subsistence Patterns of Prehistoric Dogs (Canis Familiaris) and Their Human Counterparts in Northeastern North America

STABLE ISOTOPIC INSIGHTS INTO THE SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS OF PREHISTORIC DOGS (CANIS FAMILIARIS) AND THEIR HUMAN COUNTERPARTS IN NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Sharon Allitt May 2011 Examining Committee Members: R. Michael Stewart, Advisory Chair, Temple University Anthony Ranere, Temple University Charles Weitz, Temple University Mark Schurr, Notre Dame University M. Anne Katzenberg, External Member, University of Calgary © Copyright 2011 by Sharon Allitt All Rights Reserved ! ii ABSTRACT Title: STABLE ISOTOPIC INSIGHTS INTO THE SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS OF PREHISTORIC DOGS (CANIS FAMILIARIS) AND THEIR HUMAN COUNTERPARTS IN NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA Candidate's Name: Sharon Allitt Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2011 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: R. Michael Stewart, Phd There are four goals to this study. The first is to investigate the diet of prehistoric dogs (Canis familiaris) in the Northeast region of North America using stable isotope analysis. The second goal of this study is to generate independent data concerning the presence or absence of C4 resources, such as maize, in the diets of dogs. Third, this study investigates the use of dog bone as a proxy for human bone in studies assessing the presence of C4 resources at archaeological sites. The fourth goal of this study is to provide a check on existing interpretations of the material, macro- and micro- botanical records as it concerns the presence or absence of C4 resources at the sites involved in this study. Stable isotope analysis is a science that allows the measuring of the abundance ratio of two stable isotopes of a particular element. -

Cooperative Stewardship Plan Hamilton – Trenton

Cooperative Stewardship Plan Hamilton – Trenton – Bordentown Marsh 2010 Published by: Cooperative Stewardship Plan for the Hamilton –Trenton – Bordentown Marsh Committee For copies and information: Friends for the Marsh c/o D &R Greenway Land Trust One Preservation Place Princeton, NJ 08540 609.924.4646; [email protected] http://www.drgreenway.org/partners.htm www.marsh‐friends.org Acknowledgements: The Friends for the Marsh and D&R Greenway Land Trust gratefully acknowledge the following who made development of this plan possible: Sherry Peck, through the National Park Service’s Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance Program, guided the process and facilitated meetings; Jay Watson, NJDEP, and Linda Mead, D&R Greenway Land Trust, provided staff support; members of Friends for the Marsh provided financial support; D&R Greenway Land Trust, Divine Word Missionaries (Point BreeZe), Mercer County Parks Commission (Roebling Park nature center), PSEG (Mercer Generating Station), and the Ukrainian American Society (Bow Hill Mansion) hosted meetings. Rider University provided logistical support. Credits: Collation of subcommittee reports, writing, and editing: Diana Raichel and Mary Allessio Leck Maps: Herb Lord Cover photographs: Dorothy Cross, provided by Michael Stewart (from D. Cross. 1956, The Archaeology of New Jersey, Volume II, The Abbott Farm); great egret – Herb Lord; and swamp at Sturgeon Pond; winter along Crosswicks Creek, seining at Spring Lake with Ned Gilmore, his son Collin, and a field trip participant, and fisherman on -

Body of Pennsylvania, the Atwater-Kent Museum, the Museum

REVIEWS 239 Philadelphia and the Development of papers offers an important and coherent account Americanist Archaeology of one major American city’s contributions to Don D. Fowler and David R. Wilcox the intellectual development of archaeology as a learned profession in the Americas. (editors) Curtis M. Hinsley’s sweeping and finely University of Alabama Press, crafted contribution leads off the volume with Tuscaloosa, 2003. xx+246 pp., 13 an insightful analysis of Philadelphia’s late-19th illus. $65.00 cloth. century social milieu that set the city apart from Boston, New York, and other eastern cities as Being a native Philadelphian, I had the good a center of intellectual foment. Hinsley sagely fortune early on to come under the infl uence observes that it was Philadelphia’s late-19th- of the cultural opportunities offered by the city. century atmosphere of “business aristocracy” Many of Philadelphia’s venerable institutions and genteel wealth that ultimately created the were routinely on my family’s list of places climate that allowed for the leaders of the to visit when going “into town,” including the city’s institutions to become some of the coun- Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the try’s prime players in the developing fi eld of Philadelphia Academy of Music, the Franklin archaeology. Presaging some of the later chap- Institute, the Philadelphia Art Museum, and the ters in the volume, Hinsley identifi es these key University Museum of the University of Penn- players as Daniel G. Brinton, Sara Stevenson, sylvania. In my career, I soon became aware of Stewart Culin, Charles C. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Riverview Cemetery Mercer County, New Jersey Section Number 7 Page 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Riverview Cemetery other names/site number 2. Location street & number 870 Centre Street not for publication city or town Trenton City vicinity state New Jersey code NJ county Mercer code 021 zip code 08611 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. See continuation sheet for additional comments. -

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES in the HISTORY of ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O. Murray Cultural Negotiations The Role of Women in the Founding of Americanist Archaeology DAVID L. BROWMAN University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London © 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Browman, David L. Cultural negotiations: the role of women in the founding of Americanist archaeology / David L. Browman. pages cm.— (Critical studies in the history of anthropology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8032-4381-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Women archaeologists—Biography. 2. Archaeology—United States—History. 3. Women archaeologists—History. 4. Archaeologists—Biography. I. Title. CC110.B76 2013 930.1092'2—dc23 2012049313 Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington. Designed by Nathan Putens. Contents Series Editors’ Introduction vii Introduction 1 1. Women of the Period 1865 to 1900 35 2. New Directions in the Period 1900 to 1920 73 3. Women Entering the Field during the “Roaring Twenties” 95 4. Women Entering Archaeology, 1930 to 1940 149 Concluding Remarks 251 References 277 Index 325 Series Editors’ Introduction REGNA DARNELL AND STEPHEN O. MURRAY David Browman has produced an invaluable reference work for prac- titioners of contemporary Americanist archaeology who are interested in documenting the largely unrecognized contribution of generations of women to its development. Meticulous examination of the archaeo- logical literature, especially footnotes and acknowledgments, and the archival records of major universities, museums, field school programs, expeditions, and general anthropological archives reveals a complex story of marginalization and professional invisibility, albeit one that will be surprising neither to feminist scholars nor to female archaeologists.