The Social Networks of Small Arms Proliferation Mapping an Aviation Enabled Supply Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Trafficking in Transnistria: The Role of Russia by Kent Harrel SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lubrano and Elizabeth Anderson Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with General University Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree May 2009 Abstract After declaring de facto independence from the Republic of Moldova in 1992, the breakaway region of Transnistria became increasingly isolated, and has emerged as a hotspot for weapons and human trafficking. Working from a Realist paradigm, this project assesses the extent to which the Russian government and military abet trafficking in Transnistria, and the way in which Russia uses trafficking as a means to adversely affect Moldova’s designs of broader integration within European spheres. This project proves necessary because the existing scholarship on the topic of Transnistrian trafficking failed to focus on the role of the Russian government and military, and in turn did not account for the ways in which trafficking hinders Moldova’s national interests. The research project utilizes sources such as trafficking policy centers, first-hand accounts, trade agreements, non-governmental organizations, and government documents. A review of the literature employs the use of secondary sources such as scholarly and newspaper articles. In short, this project develops a more comprehensive understanding of Russia’s role in Moldovan affairs and attempts to add a significant work to the existing literature. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

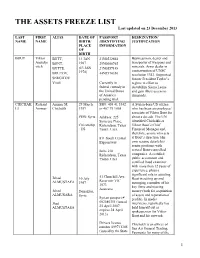

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network. -

Bout Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE May 6, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA GARRISON COURTNEY OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-7977 U.S. ANNOUNCES INDICTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER FOR CONSPIRACY TO KILL AMERICANS AND RELATED TERRORISM CHARGES MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," for, among other things, conspiring to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. BOUT was arrested by Thai authorities on a provisional arrest warrant on April 9, 2008, based on a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, charging conspiracy to provide material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. According to the Indictment unsealed today in Manhattan federal court: BOUT, an international weapons trafficker since the 1990s, has carried out his weapons-trafficking business by assembling a fleet of cargo airplanes capable of transporting weapons and military equipment to various parts of the world, including Africa, South America and the Middle East. -

Viktor Bout Arrested

VIKTOR BOUT ARRESTED Curious. The Thais just arrested the noted Russian arms dealer, Viktor Bout. For years, Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout has made millions of dollars allegedly delivering weapons and ammunition to warlords and militants. Officials believe many of his activities may be illegal, and on Thursday, Thai police announced his arrest. Bout, 41, has made his deliveries to Africa, Asia and the Mideast, using obsolete or surplus Soviet-era cargo planes. [snip] According to U.S. officials, Bout — a former Soviet air force officer who speaks multiple languages — has what is reputed to be the largest private fleet of Soviet-era cargo aircraft in the world. Bout acquired the planes shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the U.S. Department of Treasury said in 2005. At that time, the U.S. Treasury announced it was freezing the assets of Bout and his associates who are all tied to former Liberian President Charles Taylor. Taylor is currently on trial at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague. Intelligence officials said he shipped large quantities of small arms to civil wars across Africa and Asia, often taking diamonds in payment from West African fighters. I say, "curious," because I doubt this could have happened without US approval–as the promise of an "announcement" in NY later today suggests. A formal announcement on his arrest is expected later in the day in New York. And it appears that actual warrant came from our DEA–in connection with Columbia’s FARC. Bout, the target of an international arrest warrant and U.S. -

African Warrior Culture

African Warrior Culture: The Symbolism and Integration of the Avtomat Kalashnikova throughout Continental Africa By Kevin Andrew Laurell Senior Thesis in History California State Polytechnic University, Pomona June 10, 2014 Grade: Advisor: Dr. Amanda Podany Laurell 1 "I'm proud of my invention, but I'm sad that it is used by terrorists… I would prefer to have invented a machine that people could use and that would help farmers with their work - for example a lawnmower."- Mikhail Kalashnikov The Automatic Kalashnikov is undoubtedly the most recognizable and iconic of all weapon systems over the past sixty-seven years. Commonly referred to as the AK or AK-47, the rifle is a symbol of both oppression and revolution in war-torn parts of the world today. Most major conflicts over the past forty years throughout Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and South America have been fought with Kalashnikov rifles. The global saturation of Kalashnikov weaponry finds its roots in the Cold War mentalities of both the Soviet Union and Western powers vying for ideological footholds and powerful spheres of influence. Oftentimes the fiercest Cold War conflicts took place in continental Africa, with both Moscow and Washington interfering with local politics and providing assistance to one group or another. While Communist-Socialist and Western Capitalist ideologies proved unsuccessful in many regions in Africa, the AK-47 remained the surviving victor. From what we know of the Cold War, millions of Automatic Kalashnikovs (as well as the patents to the weapons) were sent to countries that were willing to discourage the threat of Western influence. -

Africa in Arms Taking Stock of Efforts for Improved Arms Control

This project is funded by the European Union Issue 03 | January 2018 Africa in arms Taking stock of efforts for improved arms control Nelson Alusala Summary The future of Africa’s development is intrinsically linked to the continent’s ability to take charge of its peace and security. The African Union (AU) Commission is best placed to lead this process. However, the organisation and its member states have continuously been challenged by the widespread and uncontrolled flow of arms and ammunition. The AU Commission and its affiliated sub-regional organisations have put into place a number of initiatives and mechanisms that align their efforts with global processes, but Africa is yet to fully enjoy the dividends of these measures. This paper reviews the achievements attained so far, explores some of the drivers of the demand for arms and identifies recommendations for bolstering existing efforts. Recommendations To strengthen current efforts, the AU, regional economic communities (RECs) and regional mechanisms (RMs) should consider the following: • Strengthening stockpile management systems within member states. This should include the construction of modern armouries and capacity building for relevant personnel. • Enforcing the implementation of arms embargoes, in collaboration with the UN sanctions committees and embargo monitoring groups. This paper focuses on: • Addressing terrorism comprehensively. Terrorism is increasingly becoming a major driver for illicit arms flows. There is an urgent need for the AU and its sub-regional organisations to coordinate efforts to eliminate this growing menace. • Regulating artisanal arms manufacturers. These manufacturers should be supported in a framework that allows them to operate in a more formalised way. -

UN Targeted Sanctions

UN Targeted Sanctions Qualitative Database June 2014 1 Al-Qaida/Taliban Overview Status: Ongoing Duration: 15 October 1999 – present (14 years +) Objective: Counter-terrorism Sanction types: Individual (asset freeze, travel ban), Diplomatic (limit diplomatic representation), Sectoral (arms embargo, aviation ban), Commodity (heroin processing chemical ban) - Territorial delimitation during EP2 (areas of Afghanistan under Taliban control) Non-UN sanctions: Regional (EU), Unilateral (US, UK, other) Other policy instruments: Diplomacy, legal tribunals, threat of force, use of force, covert measures Background In August 1998, the US embassies in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Nairobi, Kenya were bombed. Afghanistan under the Taliban was mentioned as a haven for terrorists in UNSCR 1193 in August 1998. In November of the same year, Usama bin Laden was indicted by the US for his involvement in the bombings. UNSCR 1214 (December 1998) included a long list of grievances against the Taliban in addition to its provision of sanctuary to terrorists. Episode 1 (15 October 1999 – 19 December 2000) Summary The UNSC imposed targeted sanctions on the Taliban regime (in control of Afghanistan at the time) for its refusal to turn over bin Laden for prosecution (UNSCR 1267). Purposes Coerce the Taliban to turn over bin Laden, constrain the Taliban from engaging in a variety of proscribed activities (particularly as haven for terrorism), and signal the Taliban for its violation of a large number of norms (on terrorism, the cultivation of drugs, the ongoing armed conflict, kidnapping of diplomatic personnel, and the treatment of women). Sanction type Aviation ban on aircraft owned, leased, or operated by the Taliban and asset freeze on the Taliban regime. -

A Rogue State Within the UAE?

Ras Al Khaimah: A Rogue State Within The UAE? February 8, 2010 This informational material is distributed by Mercury Public Affairs LLC, Registration Number 5953 under the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq, on behalf of its foreign principal His Highness Sheikh Khalid bin Saqr Al Qasimi. Additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. A Rogue State Within the UAE? CONTENTS Overview ........................................................................................................................3 Key Findings ..................................................................................................................4 Iran and Ras Al Khaimah ...............................................................................................5 Isfahan City Center ................................................................................................5 RAK Ceramics .........................................................................................................6 Iranian Activity in the RAK Free Trade Zone ...........................................................7 Gas, Oil and Pipeline Projects ..................................................................................8 Diamonds ....................................................................................................................14 Sunni Extremists and Al Qaeda ....................................................................................20 RAK Ofshore: the Cayman -

Most Wanted Arms Trafficker Arrested in Thailand – on World-Check Since

Release: Immediate World-Check Users warned of Suspected Arms Dealer Eight Years Ahead of his Arrest LONDON, 13 March, 2008: World-Check, the leading global provider of structured risk intelligence, is proud to announce that its researchers profiled Viktor Bout, suspected arms trafficker recently arrested in Thailand, as far back as 2000. World- Check has once again warned clients of the risks of doing business with an individual whose assets have also been frozen by various sanctions agencies. If convicted, Bout could face 10 years in prison on the Thai charge, and 15 years in the U.S., which is seeking Bout's extradition. On the 6th of March 2008 Bout was arrested by Thai officials in Bangkok on the suspicion of supplying weapons to the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and of supplying huge arms shipments into Africa’s civil wars with his own private air fleet. Bout has reportedly built a network of air cargo companies with at least sixty aircraft in the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe and the United States. He is also alleged to have supported the former president of Liberia, Charles Taylor’s regime in an effort to destabilize Sierra Leone and gain illicit access to diamonds. Bout has in the past been linked to various African leaders such as Jonas Savimbi (deceased), Mobutu Seko (deceased), and Mohammar Gadhafi among others. He also allegedly holds five passports, including two Russian and one Ukrainian. In December 2004 reports emerged of Bout’s business involvement in a Texas based charter firm that made repeated flights into Iraq, via a Pentagon contract allowing it to refuel at US military bases. -

Beyond Viktor Bout: Why the United States Needs an Arms Trade Treaty

156 Oxfam Briefing Paper 6 October 2011 Beyond Viktor Bout: Why the United States needs an Arms Trade Treaty www.oxfam.org A discarded military tank in Sierra Leone being used to dry washing. During the civil war of 1991–2002, the country was under a UN arms embargo, which arms brokers routinely broke. ©Jane Gibbs/Oxfam While the high profile trial of Viktor Bout in New York will show some of the threats the world continues to face from unscrupulous private arms brokers, it only provides a glimpse into a much larger problem. Skilled at operating in the shadows and exploiting weak national arms transfer controls, arms brokers have funneled arms to almost every country under a UN arms embargoes in the last 15 years, often fueling armed conflict and serious human rights violations. The US has worked on at least 70 US prosecutions in the last five years that have charged defendants with crimes related to illegal arms brokering. Yet, it continues to face difficulties in bringing arms brokers to justice and shutting down criminal networks. The lack of effective legal systems addressing the arms trade in many countries enables illicit arms dealers to exploit regulatory gaps and carry out their activities with impunity. The US and the world need an effective global Arms Trade Treaty to help close these gaps and stop the irresponsible trade in deadly weapons. Summary With the trial of Viktor Bout nearly underway and the UN negotiations on an Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) starting in the summer of 2012, this briefing paper seeks to provide the reader with a deeper understanding of the challenges the US government faces in tackling unscrupulous arms brokers abroad, and to show how the adoption of a strong and comprehensive ATT could help the United States and other governments in such efforts. -

Russian Strategic Intentions

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Russian Strategic Intentions A Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) White Paper May 2019 Contributing Authors: Dr. John Arquilla (Naval Postgraduate School), Ms. Anna Borshchevskaya (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.), Mr. Pavel Devyatkin (The Arctic Institute), MAJ Adam Dyet (U.S. Army, J5-Policy USCENTCOM), Dr. R. Evan Ellis (U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute), Mr. Daniel J. Flynn (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)), Dr. Daniel Goure (Lexington Institute), Ms. Abigail C. Kamp (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Roger Kangas (National Defense University), Dr. Mark N. Katz (George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government), Dr. Barnett S. Koven (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Jeremy W. Lamoreaux (Brigham Young University- Idaho), Dr. Marlene Laruelle (George Washington University), Dr. Christopher Marsh (Special Operations Research Association), Dr. Robert Person (United States Military Academy, West Point), Mr. Roman “Comrade” Pyatkov (HAF/A3K CHECKMATE), Dr. John Schindler (The Locarno Group), Ms. Malin Severin (UK Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC)), Dr. Thomas Sherlock (United States Military Academy, West Point), Dr. Joseph Siegle (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University), Dr. Robert Spalding III (U.S. Air Force), Dr. Richard Weitz (Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Prefaces Provided By: RDML Jeffrey J. Czerewko (Joint Staff, J39), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Editor: Ms.