Of Foxes and Chickensof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012 Hansen's Northwest Native Plant Database www.nwplants.com Foreword Once upon a time, there was a very kind older gentleman who loved native plants. He lived in the Pacific northwest, so plants from this area were his focus. As a young lad, his grandfather showed him flowers and bushes and trees, the sweet taste of huckleberries and strawberries, the smell of Giant Sequoias, Incense Cedars, Junipers, pines and fir trees. He saw hummingbirds poking Honeysuckles and Columbines. He wandered the woods and discovered trillium. When he grew up, he still loved native plants--they were his passion. He built a garden of natives and then built a nursery so he could grow lots of plants and teach gardeners about them. He knew that alien plants and hybrids did not usually live peacefully with natives. In fact, most of them are fierce enemies, not well behaved, indeed, they crowd out and overtake natives. He wanted to share his information so he built a website. It had a front page, a page of plants on sale, and a page on how to plant natives. But he wanted more, lots more. So he asked for help. I volunteered and he began describing what he wanted his website to do, what it should look like, what it should say. He shared with me his dream of making his website so full of information, so inspiring, so educational that it would be the most important source of native plant lore on the internet, serving the entire world. -

Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Trafficking in Transnistria: The Role of Russia by Kent Harrel SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lubrano and Elizabeth Anderson Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with General University Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree May 2009 Abstract After declaring de facto independence from the Republic of Moldova in 1992, the breakaway region of Transnistria became increasingly isolated, and has emerged as a hotspot for weapons and human trafficking. Working from a Realist paradigm, this project assesses the extent to which the Russian government and military abet trafficking in Transnistria, and the way in which Russia uses trafficking as a means to adversely affect Moldova’s designs of broader integration within European spheres. This project proves necessary because the existing scholarship on the topic of Transnistrian trafficking failed to focus on the role of the Russian government and military, and in turn did not account for the ways in which trafficking hinders Moldova’s national interests. The research project utilizes sources such as trafficking policy centers, first-hand accounts, trade agreements, non-governmental organizations, and government documents. A review of the literature employs the use of secondary sources such as scholarly and newspaper articles. In short, this project develops a more comprehensive understanding of Russia’s role in Moldovan affairs and attempts to add a significant work to the existing literature. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

Targeting Spoilers the Role of United Nations Panels of Experts

Targeting Spoilers The Role of United Nations Panels of Experts Alix J. Boucher and Victoria K. Holt Report from the Project on Rule of Law in Post-Conflict Settings Future of Peace Operations January 2009 Stimson Center Report No. 64 2 | Alix J. Boucher and Victoria K. Holt Copyright © 2009 The Henry L. Stimson Center Report Number 64 Cover photo: United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI) peacekeepers conduct arms embargo inspections on government forces in western Côte d'Ivoire. Cover design by Shawn Woodley All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from the Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19 th Street, NW 12 th Floor Washington, DC 20036 telephone: 202.223.5956 fax: 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Targeting Spoilers: The Role of United Nations Panels of Experts | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................4 Preface ..............................................................................................................................................5 List of Acronyms ..............................................................................................................................8 List of Figures, Tables, and Sidebars ..............................................................................................10 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................11 -

October 15, 2013 5% DISCOUNT on New Release Items Through Oct 22

OCTOBER NEW RELEASE GUIDE STREET DATE: October 15, 2013 5% DISCOUNT on New Release Items through Oct 22 Burnside Distribution Corp, 6635 N. Baltimore Ave, Suite 285, Portland, OR, 97203 phone (503) 231-0876 / fax (503) 231-0420 / www.bdcdistribution.com BDC New Releases Oct 2013 (503) 231-0876 / www.bdcdistribution.com 2 Oct 2013 Welcome!!BDC Welcome!! New Releases Augie Meyers - often imitated; never duplicated. A legend whose 50+ year career has resulted in Sean Chambers has not been in a hurry - he knows that patience is a virtue, good things come to those who wait, you can’t hurry love and a half-dozen other aphorisms. He spent five years with Grammys, chart hits and 17 solo albums. Here is the latest; a Texas-centric Country album with Hubert Sumlin before going solo and has only now released his fifth album in a decade and a nods toward Harlan Howard and Lefty Frizell. He is one of a kind. half; a patient man who records music he wishes to instead of dropping some kind of a new Recess Monkey is from Seattle but known nationally with great press, exposure on SiriusXM Kids album every other year just to tour behind. The Rock House Sessions is more than worth the wait. Place Live due to member Jack Forman’s daily program and their tenth(!) release. And check out In the last couple of years, Burnside has reached an affinity with Minneapolis bands; be it The these new ones by Quiet Life (on tour with The Head and The Heart), Modern Kin, Vikesh Kapoor, Shouting Matches, Polica, Solid Gold, The Ocean Blue or Davina and the Vagabonds, we’ve been Field Study, Patrick Park and Son of Stan. -

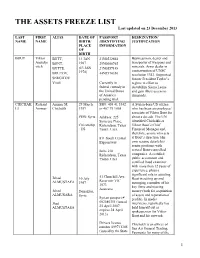

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network. -

Bout Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE May 6, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA GARRISON COURTNEY OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-7977 U.S. ANNOUNCES INDICTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER FOR CONSPIRACY TO KILL AMERICANS AND RELATED TERRORISM CHARGES MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," for, among other things, conspiring to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. BOUT was arrested by Thai authorities on a provisional arrest warrant on April 9, 2008, based on a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, charging conspiracy to provide material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. According to the Indictment unsealed today in Manhattan federal court: BOUT, an international weapons trafficker since the 1990s, has carried out his weapons-trafficking business by assembling a fleet of cargo airplanes capable of transporting weapons and military equipment to various parts of the world, including Africa, South America and the Middle East. -

Be Bold, Assume Good Faith, and There Are No Firm Rules

Wikipedia @ 20 Three links: Be bold, assume good faith, and there are no rm rules Amy Carleton, Rebecca Thorndike-Breeze, Cecelia A. Musselman Published on: Jun 26, 2019 Updated on: Aug 27, 2019 License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0) Wikipedia @ 20 Three links: Be bold, assume good faith, and there are no rm rules Three links in what? A chainmail mesh that protects against despair, fake news, and cynicism. Overstatement? Perhaps. Like all compelling utopias, Wikipedia and working in the Wikipedia community does have a dark underside. But let’s look at the light . The Working Wikipedia Collaborative is a group of scholars, teachers, archivists, and librarians working with Wikipedia in higher ed in the Boston area — all women, some rogues, and all convinced of the educational and societal value of the utopian Wikipedia project. Three of us share our stories in this chapter, but these are just a part of the work the Collaborative has done together — workshops local, national, and global, presentations, in-class orientations, cross-institutional visits, publications, edit-a-thons, mentoring circles, and elevator pitches. Collaborative members are active sharers in the participatory and collaborative knowledge creation movement that some have come to call Wikiworld. We always write as the Working Wikipedia Collaborative, but each of our origin stories is unique — and strongly shaped by working with and on Wikipedia. For us, working with the encyclopedia and its community has been a valuable forging ground, shaping each of us into links in a wide-reaching mesh of personal and professional connections. -

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

CMS/StC32/Inf.4 Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme REPORT OF THE FOURTEENTH MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS Bonn, Germany, 14-17 March 2007 1. Opening remarks 1. Prof. Colin Galbraith (Vice-Chairman) called the meeting to order at 09:10 of Thursday, 15 March 2007, and welcomed delegates to Bonn and to the 14 th meeting of the Scientific Council, particularly mentioning the councillors from Yemen and Madagascar attending their first Scientific Council since their countries’ accession. As Mr. John Mshelbwala (Chairman) had been unexpectedly delayed, Prof. Galbraith announced that he would deputise until such time as Mr. Mshelbwala could take over the chairmanship of the meeting. 1 2. COP8 in Nairobi, 20-25 November 2005, had been a successful meeting and now nearly one and half years on, it was necessary to review progress and focus on the key issues identified at the COP as well as some new ones which had arisen since. 3. It was important for the Scientific Council to maintain its deserved reputation for scientific integrity, to address the issue of climate change and its effect on migratory species and to maximise the opportunities presented by greater political interest in CMS’s core work. As a result of that greater interest the Scientific Council had to ensure the utmost accuracy of its work as its advice would come under greater scrutiny. Prof. Galbraith urged delegates to participate fully in the meeting. -

Monitoring UN Sanctions in Africa: the Role of Panels of Experts

14 Monitoring UN sanctions in Africa: the role of panels of experts Alex Vines ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ The early 1990s saw a dramatic increase in the number of sanctions imposed on countries by the United Nations Security Council. Until then sanctions had only been imposed on two countries: Rhodesia in 1966 and South Africa in 1977. During the 1990s and up to 2003 the Council imposed sanctions on: Iraq in 1990; the former Yugoslavia in 1991, 1992 and 1998; Libya in 1992; Liberia in 1992 and 2001; Somalia in 1992; Haiti in 1993; parts of Angola in 1993, 1997 and 1998; Rwanda in 1994; Sudan in 1996, Sierra Leone in 1997; Afghanistan in 1999; Ethiopia and Eritrea in 2000; and parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo () from July 2003.1 Instruments vested in the Council as part of the peace and security mechanisms envisioned in Chapter of the Charter provide the basis for the imposition of sanctions by the Council. Such sanctions have been the cause of significant debate and controversy, not least because of the humanitarian crisis in Iraq during the 1990s, which was related to, if not directly caused by, the imposition of sanctions. Sanctions have been a particular tool used in response to crises in Africa in recent years. Secretary-General Kofi Annan noted in his 1998 report that ‘sanctions, as preventive or punitive measures, have the potential to encourage political dialogue, while the application of rigorous economic and political sanctions can diminish the capacity of the protagonists to sustain a prolonged fight’.2 The most widespread type of sanction used in Africa is the arms embargo, such as those imposed on Angola, Ethiopia/Eritrea, Liberia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Somalia, and in 2003 on parts of the . -

Viktor Bout Arrested

VIKTOR BOUT ARRESTED Curious. The Thais just arrested the noted Russian arms dealer, Viktor Bout. For years, Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout has made millions of dollars allegedly delivering weapons and ammunition to warlords and militants. Officials believe many of his activities may be illegal, and on Thursday, Thai police announced his arrest. Bout, 41, has made his deliveries to Africa, Asia and the Mideast, using obsolete or surplus Soviet-era cargo planes. [snip] According to U.S. officials, Bout — a former Soviet air force officer who speaks multiple languages — has what is reputed to be the largest private fleet of Soviet-era cargo aircraft in the world. Bout acquired the planes shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the U.S. Department of Treasury said in 2005. At that time, the U.S. Treasury announced it was freezing the assets of Bout and his associates who are all tied to former Liberian President Charles Taylor. Taylor is currently on trial at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague. Intelligence officials said he shipped large quantities of small arms to civil wars across Africa and Asia, often taking diamonds in payment from West African fighters. I say, "curious," because I doubt this could have happened without US approval–as the promise of an "announcement" in NY later today suggests. A formal announcement on his arrest is expected later in the day in New York. And it appears that actual warrant came from our DEA–in connection with Columbia’s FARC. Bout, the target of an international arrest warrant and U.S. -

Portlandia: Season 2 IFC's Hit Sketch Comedy Series Created, Written By, and Starring Fred Armisen (SNL) and Carrie Brownstein

Portlandia: Season 2 IFC's hit sketch comedy series created, written by, and starring Fred Armisen (SNL) and Carrie Brownstein Description Portlandia is IFC's hit sketch comedy series created, written by, and starring Fred Armisen (SNL) and Carrie Brownstein (WILD FLAG, Sleater-Kinney vocalist/guitarist). The show is driven by a series of hilarious character-based shorts all of which take place in "Portlandia", the creators' dreamy and absurd rendering of Portland, Oregon where 90s culture reigns supreme and political correctness is all the rage. Bonus Materials Brunch Village Special 9 Behind the Scenes Videos Intro to Portlandia Special Portlandia the Tour: Seattle - Behind the scenes footage and highlights from the Portlandia Tour in Seattle with appearances by Kyle McLaughlin and Dan Savage COMMENTARY TRACK - TWO EPISODES Deleted Scene Sales Points Second season of the hit show Airs on IFC - season three starting in 2013 National publicity and advertising campaign Press: “a funhouse mirror reflection of Portland, Ore., a city that takes its progressivism - and its diet - very seriously. The satire is fresh, organic and cage-free.” —The Washington Post “endearingly hilarious” —Rob Perez, Just Press Play SKU# BRO1911 Street Date: 09/25/12 Box Lot: 30 Audio: STEREO UPC: 778854191198 Pre-Book Date: 08/21/12 Run Time: 220 min. Genre: Comedy Format: Blu-ray Disc SRP: $24.95 # of Discs: 2 disc(s) Label: VIDEO SERV Year of Production: 2011 Rating: NR Actors: Fred Armisen, Carrie Brownstein P 800.888.0486 F 610.650.9102 PO Box 280, Oaks, PA 19456 www.MVDb2b.com Publicity: Clint Weiler 610.650.8200 x115 [email protected].