The Merchant of Death ]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Groups: a Tier-One Security Priority

Armed Groups: A Tier-One Security Priority Richard H. Shultz Douglas Farah Itamara V. Lochard INSS Occasional Paper 57 September 2004 USAF Institute for National Security Studies USAF Academy, Colorado ii The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the US Government. The paper is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. The Consortium for the Study of Intelligence holds copyright to this paper; it is published here with their permission. ******* ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Richard H. Shultz, Jr. is director of the International Security Studies Program at the The Fletcher School and Professor of International Politics. At the Consortium for the Study of Intelligence he serves as research director. He has served as a consultant to US government agencies concerned with national security affairs. He has also written extensively on intelligence and security. He recently published “SHOWSTOPPERS: Nine Reasons Why We Never Sent Our Special Operations Forces after Al Qaeda Before 9/11,” Weekly Standard 9:19 (26 January 2004). His forthcoming book is Tribal Warfare: How Non-State Armed Groups Fight (Columbia University Press, 2005). Douglas Farah is senior fellow at the Consortium for the Study of Intelligence. For 19 years worked as a foreign correspondent and investigative reporter for the Washington Post, covering armed conflicts, insurgencies, and organized crime in Latin America and West Africa. He has also written on Middle Eastern terror finance, including Blood From Stones: The Secret Financial Network of Terror (2004). -

Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Trafficking in Transnistria: The Role of Russia by Kent Harrel SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lubrano and Elizabeth Anderson Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with General University Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree May 2009 Abstract After declaring de facto independence from the Republic of Moldova in 1992, the breakaway region of Transnistria became increasingly isolated, and has emerged as a hotspot for weapons and human trafficking. Working from a Realist paradigm, this project assesses the extent to which the Russian government and military abet trafficking in Transnistria, and the way in which Russia uses trafficking as a means to adversely affect Moldova’s designs of broader integration within European spheres. This project proves necessary because the existing scholarship on the topic of Transnistrian trafficking failed to focus on the role of the Russian government and military, and in turn did not account for the ways in which trafficking hinders Moldova’s national interests. The research project utilizes sources such as trafficking policy centers, first-hand accounts, trade agreements, non-governmental organizations, and government documents. A review of the literature employs the use of secondary sources such as scholarly and newspaper articles. In short, this project develops a more comprehensive understanding of Russia’s role in Moldovan affairs and attempts to add a significant work to the existing literature. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

Iran's Extending Influence in the Western Hemisphere

THREAT TO THE HOMELAND: IRAN’S EXTENDING INFLUENCE IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND MANAGEMENT EFFICIENCY OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 9, 2013 Serial No. 113–24 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 85–689 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi PETER T. KING, New York LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan, Vice Chair BRIAN HIGGINS, New York PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania RON BARBER, Arizona JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah DONDALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey STEVEN M. PALAZZO, Mississippi BETO O’ROURKE, Texas LOU BARLETTA, Pennsylvania TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii CHRIS STEWART, Utah FILEMON VELA, Texas RICHARD HUDSON, North Carolina STEVEN A. HORSFORD, Nevada STEVE DAINES, Montana ERIC SWALWELL, California SUSAN W. BROOKS, Indiana SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania MARK SANFORD, South Carolina GREG HILL, Chief of Staff MICHAEL GEFFROY, Deputy Chief of Staff/Chief Counsel MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND MANAGEMENT EFFICIENCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina, Chairman PAUL C. -

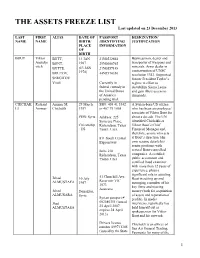

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network. -

Bout Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE May 6, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA GARRISON COURTNEY OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-7977 U.S. ANNOUNCES INDICTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER FOR CONSPIRACY TO KILL AMERICANS AND RELATED TERRORISM CHARGES MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," for, among other things, conspiring to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. BOUT was arrested by Thai authorities on a provisional arrest warrant on April 9, 2008, based on a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, charging conspiracy to provide material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. According to the Indictment unsealed today in Manhattan federal court: BOUT, an international weapons trafficker since the 1990s, has carried out his weapons-trafficking business by assembling a fleet of cargo airplanes capable of transporting weapons and military equipment to various parts of the world, including Africa, South America and the Middle East. -

Viktor Bout Arrested

VIKTOR BOUT ARRESTED Curious. The Thais just arrested the noted Russian arms dealer, Viktor Bout. For years, Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout has made millions of dollars allegedly delivering weapons and ammunition to warlords and militants. Officials believe many of his activities may be illegal, and on Thursday, Thai police announced his arrest. Bout, 41, has made his deliveries to Africa, Asia and the Mideast, using obsolete or surplus Soviet-era cargo planes. [snip] According to U.S. officials, Bout — a former Soviet air force officer who speaks multiple languages — has what is reputed to be the largest private fleet of Soviet-era cargo aircraft in the world. Bout acquired the planes shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the U.S. Department of Treasury said in 2005. At that time, the U.S. Treasury announced it was freezing the assets of Bout and his associates who are all tied to former Liberian President Charles Taylor. Taylor is currently on trial at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague. Intelligence officials said he shipped large quantities of small arms to civil wars across Africa and Asia, often taking diamonds in payment from West African fighters. I say, "curious," because I doubt this could have happened without US approval–as the promise of an "announcement" in NY later today suggests. A formal announcement on his arrest is expected later in the day in New York. And it appears that actual warrant came from our DEA–in connection with Columbia’s FARC. Bout, the target of an international arrest warrant and U.S. -

African Warrior Culture

African Warrior Culture: The Symbolism and Integration of the Avtomat Kalashnikova throughout Continental Africa By Kevin Andrew Laurell Senior Thesis in History California State Polytechnic University, Pomona June 10, 2014 Grade: Advisor: Dr. Amanda Podany Laurell 1 "I'm proud of my invention, but I'm sad that it is used by terrorists… I would prefer to have invented a machine that people could use and that would help farmers with their work - for example a lawnmower."- Mikhail Kalashnikov The Automatic Kalashnikov is undoubtedly the most recognizable and iconic of all weapon systems over the past sixty-seven years. Commonly referred to as the AK or AK-47, the rifle is a symbol of both oppression and revolution in war-torn parts of the world today. Most major conflicts over the past forty years throughout Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and South America have been fought with Kalashnikov rifles. The global saturation of Kalashnikov weaponry finds its roots in the Cold War mentalities of both the Soviet Union and Western powers vying for ideological footholds and powerful spheres of influence. Oftentimes the fiercest Cold War conflicts took place in continental Africa, with both Moscow and Washington interfering with local politics and providing assistance to one group or another. While Communist-Socialist and Western Capitalist ideologies proved unsuccessful in many regions in Africa, the AK-47 remained the surviving victor. From what we know of the Cold War, millions of Automatic Kalashnikovs (as well as the patents to the weapons) were sent to countries that were willing to discourage the threat of Western influence. -

Africa in Arms Taking Stock of Efforts for Improved Arms Control

This project is funded by the European Union Issue 03 | January 2018 Africa in arms Taking stock of efforts for improved arms control Nelson Alusala Summary The future of Africa’s development is intrinsically linked to the continent’s ability to take charge of its peace and security. The African Union (AU) Commission is best placed to lead this process. However, the organisation and its member states have continuously been challenged by the widespread and uncontrolled flow of arms and ammunition. The AU Commission and its affiliated sub-regional organisations have put into place a number of initiatives and mechanisms that align their efforts with global processes, but Africa is yet to fully enjoy the dividends of these measures. This paper reviews the achievements attained so far, explores some of the drivers of the demand for arms and identifies recommendations for bolstering existing efforts. Recommendations To strengthen current efforts, the AU, regional economic communities (RECs) and regional mechanisms (RMs) should consider the following: • Strengthening stockpile management systems within member states. This should include the construction of modern armouries and capacity building for relevant personnel. • Enforcing the implementation of arms embargoes, in collaboration with the UN sanctions committees and embargo monitoring groups. This paper focuses on: • Addressing terrorism comprehensively. Terrorism is increasingly becoming a major driver for illicit arms flows. There is an urgent need for the AU and its sub-regional organisations to coordinate efforts to eliminate this growing menace. • Regulating artisanal arms manufacturers. These manufacturers should be supported in a framework that allows them to operate in a more formalised way. -

Trump’S Business Interests

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

Alternative Governance in the Northern Triangle and Implications for U.S

1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301- 459- 3366 | www.rowman.com Alternative Governance in the Northern Triangle and Implications for U.S. Foreign Policy Finding Logic within Chaos AUTHORS Douglas Farah Carl Meacham ISBN 978-1-4422-5884-6 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington,Ë|xHSLEOCy258846z DC 20036v*:+:!:+:! 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org A Report of the CSIS Americas Program SEPTEMBER 2015 Blank Alternative Governance in the Northern Triangle and Implications for U.S. Foreign Policy Finding Logic within Chaos AUTHORS Douglas Farah Carl Meacham A Report of the CSIS Americas Program September 2015 Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-62534_ch00_3P.indd 1 9/11/15 10:35 AM hn hk io il sy SY eh ek About CSIS hn hk io il sy SY eh ek For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked hn hk io il sy SY eh ek to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are hn hk io il sy SY eh ek providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart hn hk io il sy SY eh ek a course toward a better world. hn hk io il sy SY eh ek CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. -

Foreign Aid and the Fight Against Terrorism and Proliferation: Leveraging Foreign Aid to Achieve U.S

FOREIGN AID AND THE FIGHT AGAINST TERRORISM AND PROLIFERATION: LEVERAGING FOREIGN AID TO ACHIEVE U.S. POLICY GOALS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TERRORISM, NONPROLIFERATION, AND TRADE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 31, 2008 Serial No. 110–225 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–840PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DAVID WU, Oregon TED POE, Texas BRAD MILLER, North Carolina BOB INGLIS, South Carolina LINDA T.