Vol 12 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1946, Volume 41, Issue No. 4

MHRYMnD CWAQAZIU^j MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE DECEMBER • 1946 t. IN 1900 Hutzler Brothers Co. annexed the building at 210 N. Howard Street. Most of the additional space was used for the expansion of existing de- partments, but a new shoe shop was installed on the third floor. It is interesting to note that the shoe department has now returned to its original location ... in a greatly expanded form. HUTZLER BPOTHERSe N\S/Vsc5S8M-lW MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE A Quarterly Volume XLI DECEMBER, 1946 Number 4 BALTIMORE AND THE CRISIS OF 1861 Introduction by CHARLES MCHENRY HOWARD » HE following letters, copies of letters, and other documents are from the papers of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (b. 1805, d. 1888). They are confined to a brief period of great excitement in Baltimore, viz, after the riot of April 19, 1861, when Federal troops were attacked by the mob while being marched through the City streets, up to May 13th of that year, when General Butler, with a large body of troops occupied Federal Hill, after which Baltimore was substantially under control of the 1 Some months before his death in 1942 the late Charles McHenry Howard (a grandson of Charles Howard, president of the Board of Police in 1861) placed the papers here printed in the Editor's hands for examination, and offered to write an introduction if the Committee on Publications found them acceptable for the Magazine. Owing to the extraordinary events related and the revelation of an episode unknown in Baltimore history, Mr. Howard's proposal was promptly accepted. -

Hong Kong Govt Ivory Sales Ban NGO Signon Letter 14

To: Hong Kong Chief Executive, Leung Chun-ying via Hong Kong Post & e-mail 14 May 2014 URGENT: Hong Kong Government Please Legislate a Permanent Ivory Sales Ban We are writing to you on behalf of a global coalition of international and local wildlife conservation and animal welfare groups, with regards to the continued sales of ivory and ivory products within the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. We are calling on the Hong Kong government to enact an urgent, comprehensive and permanent ban on ivory sales. We applaud the government for taking a brave step in January 2014 to commit to the destruction by incineration of 29.6 tonnes of confiscated elephant ivory seized in Hong Kong since 1976. However, we believe that this does not go far enough, and that more needs to be done to curb demand for ivory and effectively diminish illegal trade and elephant poaching. Hong Kong plays a key role in the global ivory trade. The city has been recognized as a major market and transit point for smuggled ivory by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), which considers Hong Kong one of nine countries / regions of priority concern. (1) The current catastrophic poaching crisis, the worst since the 1980s, is causing the killing of tens of thousands of elephants every year for the illegal ivory trade. Much of this ivory passes through Hong Kong illegally on the way to mainland China, where demand is surging. This demand is driven in large part by a new class of wealthy individuals, many of whom travel to Hong Kong as tourists to buy tax free luxury goods – including ivory and ivory products. -

Cop18 Documents

Original language: English CoP18 Com. II Rec. 4 (Rev. 1) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17 - 28 August 2019 Summary record of the fourth session for Committee II 19 August 2019: 14h10 - 16h50 Chairs: C. Hoover (United States of America) Secretariat: I. Higuero Y. Liu D. Morgan H. Okusu Rapporteurs: A. Caromel E. Jennings R. Mackenzie C. Stafford 17.2 Proposed amendments to Resolution Conf. 4.6 (Rev. CoP17) and Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17) (contd.) and 18.3 Proposed amendments to Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17) (contd.) South Africa noted its support for the proposed decisions contained in Annex 1 to document CoP18 Doc. 18.1 (Rev. 1) revised by the Secretariat to reflect recommendations found in documents CoP18 Doc. 17.2, 17.3, 18.2, and 18.3. Bangladesh and Eswatini supported additional engagement of local communities in CITES processes. China supported the creation of an in-session working group to discuss further amendments to both documents. New Zealand and Indonesia did not support the amendments suggested in either document CoP18 Doc. 17.2 or CoP18 Doc. 18.3. Though they recognised the importance of consulting rural communities, they echoed earlier comments by Burkina Faso, Colombia, Gabon, Israel, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger and Nigeria that socioeconomic impacts of proposed listings should best be determined at the national level. New Zealand and Indonesia instead supported the suggestion by the United States of America to create guidance to support the engagement processes outlined in Resolution Conf. -

1 Eighteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties / Dix

Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties / Dix-huitième session de la Conférence des Parties / Decimoctava reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019, Genève (Suisse), 17-28 août 2019, Ginebra (Suiza), 17-28 de Agosto de 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS / LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS / LISTA DE PARTICIPANTES [1,694 participant(e)s] PARTIES / PARTES Afghanistan Mr. Ezatullah SEDIQI Afghanistan Mr. Jalaludin NASERI Afghanistan Mr. Qais SAHAR Algeria H.E. Mr. Boudjemaa DELMI Algeria Ms. Ouahida BOUCEKKINE Algeria Mr. Ali MAHMOUDI Algeria Mr. Hichem AYADAT Angola H.E. Ms. Paula Cristina COELHO Angola H.E. Ms. Margarida IZATA Angola Ms. Albertina Nzuzi MATIAS Angola Ms. Esperanca Maria E Francisco DA COSTA Angola Mr. Lucas Marculino MIRANDA Angola Mr. Soki KUEDIKUENDA Angola Mr. Lucas Ramos Dos SANTOS Angola Mr. Velasco Cavaco CHIPALANGA Angola Ms. Violante Isilda de Azevedo PEREIRA Angola Ms. Custodia Canjimba SINELA Angola Ms. Tamar RON Angola Mr. Miguel Nvambanu KINAVUIDI Angola Mr. Olivio Afonso PANDA Angola Mr. Alberto Samy GUIMARAES Angola Mr. Antonio NASCIMENTO Antigua and Barbuda Ms. Tricia LOVELL Antigua and Barbuda Mr. Daven JOSEPH Argentina H.E. Mr. Carlos Mario FORADORI Argentina Ms. Vanesa Patricia TOSSENBERGER Argentina Mr. Germán PROFFEN Armenia Ms. Natalya SAHAKYAN Australia Ms. Sarah GOWLAND Australia Ms. Rhedyn OLLERENSHAW Australia Mr. Damian WRIGLEY Australia Mr. Nicholas BOYLE Australia Mr. Cameron KERR Australia Mr. John GIBBS Austria Mr. Maximilian ABENSPERG-TRAUN 1 Austria Mr. Martin ROSE Austria Ms. Gerald BENYR Austria Ms. Nadja ZIEGLER Azerbaijan Ms. Gunel MAMMADLI Bahamas Mr. Maurice ISAACS Bahamas Ms. Deandra DELANCEY-MILFORT Bahamas Mr. -

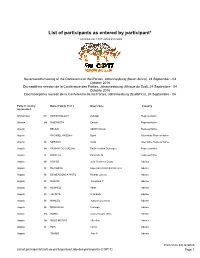

List of Participants As Entered by Participant* * Excludes Over 1,500 Visitors and Media

List of participants as entered by participant* * excludes over 1,500 visitors and media Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties, Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September - 04 October 2016 Dix-septième session de la Conférence des Parties, Johannesbourg (Afrique du Sud), 24 Septembre - 04 Octobre 2016 Decimoséptima reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes, Johannesburg (Sudáfrica), 24 Septiembre - 04 Party or country Name (Family, First ) Given name Category represented Afghanistan Mr KARIMI BALOCH Zolfaqar Representative Albania Ms RABDHISTA Eneida Representative Algeria BELAID Abd-El-Naceur Representative Algeria KACIMIEL HASSANI Djalal Alternative Representative Algeria Mr MESBAH Reda Alternative Representative Angola Ms FRANCISCO COELHO Paula Cristina Domingos Representative Angola Dr NICOLAU Benvindo M Representative Angola Mr BANGO Julio Cristóvao Diogo Adviser Angola Dr DA COSTA Esperanca Maria E Francisco Adviser Angola Mr DE MENDONCA PINTO Nivaldo Lukeny Adviser Angola Mr DIAKITE Josephina P Adviser Angola MrHUONGO Abias Adviser Angola MrJACINTO D Orlando Adviser Angola Mr MANUEL Joaquim Lourenzo Adviser Angola MrMIAKONGO Lusanga Adviser Angola Ms NOBRE Luana Nayole Silva Adviser Angola Ms NZUZI MATIAS Albertina Adviser Angola DrRON Tamar Adviser Angola SAMBO Jose A Adviser Printed on 12/12/2016 List of participants/Lista de participantes/Liste des participants (COP17) Page: 1 Antigua and Barbuda Mr JOSEPH Daven C Representative Argentina Mr FIGUEROA Javier Esteban Representative Argentina Ms HURTADO Patricia Edith -

The Nimitz Graybook: How the United States Naval War College Influenced the Pacific Campaign During World War II

THE NIMITZ GRAYBOOK: HOW THE UNITED STATES NAVAL WAR COLLEGE INFLUENCED THE PACIFIC CAMPAIGN DURING WORLD WAR II ___________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Sam Houston State University ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ___________ by Lisbeth A. Hargraves May, 2020 THE NIMITZ GRAYBOOK: HOW THE UNITED STATES NAVAL WAR COLLEGE INFLUENCED THE PACIFIC CAMPAIGN DURING WORLD WAR II by Lisbeth A. Hargraves ___________ APPROVED: Brian Jordan, PhD Committee Director Jeremiah Dancy, PhD Committee Co-Director Benjamin Park, PhD Committee Member Abbey Zink, PhD Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband who encouraged me to pursue my dreams. Thank you to my Academic Advisor who guided me through the process and kept me on track despite numerous hurdles both big and small. iii ABSTRACT Hargraves, Lisbeth A. The Nimitz Graybook: How the United States Naval War College Influenced the Pacific Campaign During World War II. Master of Arts (History), May, 2020, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. The Nimitz Graybook is an eight-volume collection of the command decisions of Fleet Admiral Nimitz. The collection covers the everyday tasking of commanders, communications and every major decision in the United States Naval Pacific Campaign from December 7, 1941 through August 31, 1945. The entire eight volume series was digitized in 2014 but scholarly research on the four-thousand-page collection has been limited to this date. While it is difficult to accurately link the effect of professional military education to the outcome of real-world battles there are some instances where this can be done. -

Historiogtl Review

Historiogtl Review The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA. MISSOURI The George Caleb Bingham portrait of Confederate jS General Joseph O. Shelby, an unlisted painting that had jg| been in the Shelby family for nearly three-quarters of a | century, is a recent gift to the State Historical Society of JS Missouri by General Shelby's grandson, J O Shelby Jersig, ffl Lt. Col. Ret., United States Marine Corps, Clovis, New gj Mexico. y A native Kentuckian, General Shelby is best remem- pi bered as a Missouri manufacturer, farmer and Confederate M cavalry general. Hailed by some authorities as the best cav alry general of the South, his Missouri forays were highlights of the Trans-Mississippi Army of the Confederacy. At the time of his death in 1897, General Shelby was United States Marshall for the western district of Missouri. m Shelby's portrait, along with fourteen other canvases, one miniature and drawings, engravings and lithographs by Bingham were prepared for display in the Art Gallery, at m the Society's Sesquicentennial Convention, October 3, 1970, and will remain on display until late summer, 1971. On exhibit in the Society's corridors are the tinted en- JU gravings of Karl Bodmer's illustrations, prepared in the field during 1833-34, for Prince Maximilians of Wied's Travels in j|j the Interior of North America, published in the 1840s. MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW Published Quarterly by THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI COLUMBIA, MISSOURI RICHARD S. BROWNLEE EDITOR DOROTHY CALDWELL ASSOCIATE EDITOR JAMES W. GOODRICH ASSOCIATE EDITOR The MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW is owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri and is published quarterly at 201 South Eighth Street, Columbia, Missouri 65201. -

Vision Document 2016 – 2025

AFRO-EURASIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, EDUCATION, DEVELOPMENT AND EMPOWERMENT (ACCEDE) Registered with the Government of Jammu and Kashmir as a Public Charitable Trust Dr. Ravi Jyee VISION DOCUMENT 2016 – 2025 AFRO-EURASIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, EDUCATION, DEVELOPMENT AND EMPOWERMENT Jammu 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION, PHILOSOPHY, ORIGINS AND ACTIVITIES The Afro-Eurasian Chamber of Commerce, Education, Development and Empowerment (ACCEDE) has been established with a view to conducting applied researches with benevolent philosophies with special reference to the functional areas related to, health, art, culture, education, literacy, labour, employability, skill development, micro, small and medium enterprises, rural development, poverty alleviation, science, technology, industrial development, management science, sports, urban development, vocationalisation, women’s empowerment, youth development etc. Established in the year 2015 as a Public Charitable Trust, the origins of this organization is based on the principles of benevolence as a non-political, non- governmental and non-profit making organizations dedicated for the cause of international development aimed at applied researches needed for ensuring the sustainable development of our society. Benevolence can be seen as optimism applied to other people and relationships. It does not consist of any particular set of actions, but a general good will towards others based on the benevolent universe premise: Successful trading relationships with others are the to be expected, so treat other people accordingly. For example, if you are optimistic about other people and relationships, then perhaps you will treat a stranger like you would normally treat an acquaintance and an acquaintance like a friend. This broadcasts a friendly, non-hostile, attitude and a willingness to trade which is a prerequisite for peaceful interaction. -

What Motivated Teachers to Teach About the Soviet Union After World War Ii

HOPE, HOSTILITY, AND INTEREST: WHAT MOTIVATED TEACHERS TO TEACH ABOUT THE SOVIET UNION AFTER WORLD WAR II ANATOLI RAPOPORT Historically, the cold war was a watershed that separated two epochs: the time of abnormal, although compelled, partnership of two political systems and the period of peaceful coexistence with barely hidden hostility. The peacefulness of the latter, however elusive and vulnerable it was from time to time, has to be credited to the cold war, a relatively short period of time in world history, when humankind, and most importantly its leaders, realized how close our world was to self-destruction. The importance of the cold war is hard to overestimate. Analyzing the origins of the cold war in history textbooks, J. Samuel Walker pointed out three distinctive periods in explaining its roots.1 For almost twenty years the American public held the conviction that postwar tensions were a result of the Soviet Union’s expansion and aggression. This opinion was also shared by the intellectual and political elite of the United States. Things started to change by the late 1960s, at the very height of the Vietnam War when historians sought to explain why Americans GI’s found themselves thousands of miles away from Chicago and Los Angeles. New Left scholars more and more often pointed at the economic expansion of American capitalism as the primary reason for the cold war. These revisionists were immediately and decisively repulsed by traditionalists. The dispute prompted a bitter scholarly debate. Observing the arising controversy, Cashman and Gilbert hailed the existing diversity but warned against the inflexibility of a priori assumptions made by revisionists and traditionalists. -

OSS Operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - the Botstiber Institute for Austrian…

17.6.2020 No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - The Botstiber Institute for Austrian… Search ... ABOUT FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES EVENTS PUBLICATIONS RESOURCES (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and Home / Blog, News / No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Liberation of the Tyrol in No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 By Peter Pirker The New York Times’ headline “Torture Endured by Brooklynite Made Innsbruck Entry Bloodless” informed the public why US troops didn’t have to fight when on May 3, 1945, they took the Austrian city of Innsbruck, the largest city in the so-called Alpine redoubt of Nazi Germany. The article featured the now famous Operation Greenup and its chief operator Frederick “Fred” Mayer. Operation Greenup was one of some thirty intelligence operations conducted by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) division for Germany and Austria from Bari, Italy, with the target region of the southern parts of Germany, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia. The OSS launched a series of other operations into the German Reich from Switzerland, France, Scandinavia and the Netherlands, but none achieved the success of Operation Greenup. Altogether, the American and British forces carried out more than 21,000 airborne and parachute operations in Europe, nearly half of which supported the partisan movement in Yugoslavia. Refugees from https://botstiberbiaas.org/no-sleep-till-brooklyn/ 1/10 17.6.2020 No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - The Botstiber Institute for Austrian… across the entire Nazi dominion in Europe, antifascists in exile and local members of the resistance were involved in this collaboration to the extent it could be referred to as a transnational resistance against the Axis Powers. -

Historical Review: "Justicia Para Todo" Judiciary History

Judiciary History - Historical Review: "Justicia para todo" War, diplomacy, social or economic pressure have been used throughout history to resolve disputes. They have literally shaped the world. Today’s court systems are a product of man’s desire to settle disputes in a more peaceful, equitable and socially acceptable manner. Method of justice continues to evolve in our land with every case or motion brought before the courts. Today’s Superior Court of Guam serves as a forum to resolve disputes locally. And though the system itself is not a product of Guam, the questions and conclusions most certainly are. This booklet is not so much a history of the courts as it is a story of the people of the island and type of justice that has prevailed on our shores. As we celebrate the opening of the new Guam Judicial Center, it is only fitting that we remember those who contributed to the growth of Guam’s courts system. Throughout the past century, the dedicated men and women who served the courts helped ensure that justice continued to prevail on our shores. It is to these fine people of yester year and those who will serve our courts in the future that this booklet is dedicated to. Thank you and Si Yuus Maase. Judiciary History - Justice on Guam: "The Chamorros" "Yanggen numa'piniti hao taotao, nangga ma na piniti-mu Mase ha apmaman na tiempo, un apasi sa' dibi-mu." Translated: When you hurt someone, wait for your turn to hurt. Even if it takes a while, you will pay because it's your debt.