The Case of Hertel V. Switzerland and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Govt Ivory Sales Ban NGO Signon Letter 14

To: Hong Kong Chief Executive, Leung Chun-ying via Hong Kong Post & e-mail 14 May 2014 URGENT: Hong Kong Government Please Legislate a Permanent Ivory Sales Ban We are writing to you on behalf of a global coalition of international and local wildlife conservation and animal welfare groups, with regards to the continued sales of ivory and ivory products within the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. We are calling on the Hong Kong government to enact an urgent, comprehensive and permanent ban on ivory sales. We applaud the government for taking a brave step in January 2014 to commit to the destruction by incineration of 29.6 tonnes of confiscated elephant ivory seized in Hong Kong since 1976. However, we believe that this does not go far enough, and that more needs to be done to curb demand for ivory and effectively diminish illegal trade and elephant poaching. Hong Kong plays a key role in the global ivory trade. The city has been recognized as a major market and transit point for smuggled ivory by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), which considers Hong Kong one of nine countries / regions of priority concern. (1) The current catastrophic poaching crisis, the worst since the 1980s, is causing the killing of tens of thousands of elephants every year for the illegal ivory trade. Much of this ivory passes through Hong Kong illegally on the way to mainland China, where demand is surging. This demand is driven in large part by a new class of wealthy individuals, many of whom travel to Hong Kong as tourists to buy tax free luxury goods – including ivory and ivory products. -

Cop18 Documents

Original language: English CoP18 Com. II Rec. 4 (Rev. 1) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17 - 28 August 2019 Summary record of the fourth session for Committee II 19 August 2019: 14h10 - 16h50 Chairs: C. Hoover (United States of America) Secretariat: I. Higuero Y. Liu D. Morgan H. Okusu Rapporteurs: A. Caromel E. Jennings R. Mackenzie C. Stafford 17.2 Proposed amendments to Resolution Conf. 4.6 (Rev. CoP17) and Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17) (contd.) and 18.3 Proposed amendments to Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17) (contd.) South Africa noted its support for the proposed decisions contained in Annex 1 to document CoP18 Doc. 18.1 (Rev. 1) revised by the Secretariat to reflect recommendations found in documents CoP18 Doc. 17.2, 17.3, 18.2, and 18.3. Bangladesh and Eswatini supported additional engagement of local communities in CITES processes. China supported the creation of an in-session working group to discuss further amendments to both documents. New Zealand and Indonesia did not support the amendments suggested in either document CoP18 Doc. 17.2 or CoP18 Doc. 18.3. Though they recognised the importance of consulting rural communities, they echoed earlier comments by Burkina Faso, Colombia, Gabon, Israel, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger and Nigeria that socioeconomic impacts of proposed listings should best be determined at the national level. New Zealand and Indonesia instead supported the suggestion by the United States of America to create guidance to support the engagement processes outlined in Resolution Conf. -

1 Eighteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties / Dix

Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties / Dix-huitième session de la Conférence des Parties / Decimoctava reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019, Genève (Suisse), 17-28 août 2019, Ginebra (Suiza), 17-28 de Agosto de 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS / LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS / LISTA DE PARTICIPANTES [1,694 participant(e)s] PARTIES / PARTES Afghanistan Mr. Ezatullah SEDIQI Afghanistan Mr. Jalaludin NASERI Afghanistan Mr. Qais SAHAR Algeria H.E. Mr. Boudjemaa DELMI Algeria Ms. Ouahida BOUCEKKINE Algeria Mr. Ali MAHMOUDI Algeria Mr. Hichem AYADAT Angola H.E. Ms. Paula Cristina COELHO Angola H.E. Ms. Margarida IZATA Angola Ms. Albertina Nzuzi MATIAS Angola Ms. Esperanca Maria E Francisco DA COSTA Angola Mr. Lucas Marculino MIRANDA Angola Mr. Soki KUEDIKUENDA Angola Mr. Lucas Ramos Dos SANTOS Angola Mr. Velasco Cavaco CHIPALANGA Angola Ms. Violante Isilda de Azevedo PEREIRA Angola Ms. Custodia Canjimba SINELA Angola Ms. Tamar RON Angola Mr. Miguel Nvambanu KINAVUIDI Angola Mr. Olivio Afonso PANDA Angola Mr. Alberto Samy GUIMARAES Angola Mr. Antonio NASCIMENTO Antigua and Barbuda Ms. Tricia LOVELL Antigua and Barbuda Mr. Daven JOSEPH Argentina H.E. Mr. Carlos Mario FORADORI Argentina Ms. Vanesa Patricia TOSSENBERGER Argentina Mr. Germán PROFFEN Armenia Ms. Natalya SAHAKYAN Australia Ms. Sarah GOWLAND Australia Ms. Rhedyn OLLERENSHAW Australia Mr. Damian WRIGLEY Australia Mr. Nicholas BOYLE Australia Mr. Cameron KERR Australia Mr. John GIBBS Austria Mr. Maximilian ABENSPERG-TRAUN 1 Austria Mr. Martin ROSE Austria Ms. Gerald BENYR Austria Ms. Nadja ZIEGLER Azerbaijan Ms. Gunel MAMMADLI Bahamas Mr. Maurice ISAACS Bahamas Ms. Deandra DELANCEY-MILFORT Bahamas Mr. -

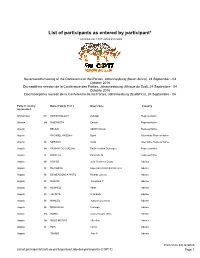

List of Participants As Entered by Participant* * Excludes Over 1,500 Visitors and Media

List of participants as entered by participant* * excludes over 1,500 visitors and media Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties, Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September - 04 October 2016 Dix-septième session de la Conférence des Parties, Johannesbourg (Afrique du Sud), 24 Septembre - 04 Octobre 2016 Decimoséptima reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes, Johannesburg (Sudáfrica), 24 Septiembre - 04 Party or country Name (Family, First ) Given name Category represented Afghanistan Mr KARIMI BALOCH Zolfaqar Representative Albania Ms RABDHISTA Eneida Representative Algeria BELAID Abd-El-Naceur Representative Algeria KACIMIEL HASSANI Djalal Alternative Representative Algeria Mr MESBAH Reda Alternative Representative Angola Ms FRANCISCO COELHO Paula Cristina Domingos Representative Angola Dr NICOLAU Benvindo M Representative Angola Mr BANGO Julio Cristóvao Diogo Adviser Angola Dr DA COSTA Esperanca Maria E Francisco Adviser Angola Mr DE MENDONCA PINTO Nivaldo Lukeny Adviser Angola Mr DIAKITE Josephina P Adviser Angola MrHUONGO Abias Adviser Angola MrJACINTO D Orlando Adviser Angola Mr MANUEL Joaquim Lourenzo Adviser Angola MrMIAKONGO Lusanga Adviser Angola Ms NOBRE Luana Nayole Silva Adviser Angola Ms NZUZI MATIAS Albertina Adviser Angola DrRON Tamar Adviser Angola SAMBO Jose A Adviser Printed on 12/12/2016 List of participants/Lista de participantes/Liste des participants (COP17) Page: 1 Antigua and Barbuda Mr JOSEPH Daven C Representative Argentina Mr FIGUEROA Javier Esteban Representative Argentina Ms HURTADO Patricia Edith -

OSS Operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - the Botstiber Institute for Austrian…

17.6.2020 No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - The Botstiber Institute for Austrian… Search ... ABOUT FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES EVENTS PUBLICATIONS RESOURCES (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and Home / Blog, News / No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Liberation of the Tyrol in No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 By Peter Pirker The New York Times’ headline “Torture Endured by Brooklynite Made Innsbruck Entry Bloodless” informed the public why US troops didn’t have to fight when on May 3, 1945, they took the Austrian city of Innsbruck, the largest city in the so-called Alpine redoubt of Nazi Germany. The article featured the now famous Operation Greenup and its chief operator Frederick “Fred” Mayer. Operation Greenup was one of some thirty intelligence operations conducted by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) division for Germany and Austria from Bari, Italy, with the target region of the southern parts of Germany, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia. The OSS launched a series of other operations into the German Reich from Switzerland, France, Scandinavia and the Netherlands, but none achieved the success of Operation Greenup. Altogether, the American and British forces carried out more than 21,000 airborne and parachute operations in Europe, nearly half of which supported the partisan movement in Yugoslavia. Refugees from https://botstiberbiaas.org/no-sleep-till-brooklyn/ 1/10 17.6.2020 No sleep till (Inns)Brooklyn: OSS operation Greenup and the Liberation of the Tyrol in May 1945 - The Botstiber Institute for Austrian… across the entire Nazi dominion in Europe, antifascists in exile and local members of the resistance were involved in this collaboration to the extent it could be referred to as a transnational resistance against the Axis Powers. -

Nation Prepares to Mark Christmas ’The Neighbors Have Been Concerned the Commission Was Also Shown the Final Plans for the Park

PAGE EIGHTEEN - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Manchester. Conn., Thurs., Dec. 23, 1976 Industrial nations Town officials About town (Continued from Page One) as that of the Hartford region, which to escape recession The weather Manchester Composite Squadron Inside today scaled by computer according to Manchester also did. Manchester unemployment level is of the Civil Air Patrol will meet PARIS (UPI) — ’The industrialized nations will escape Partly sunny, breezy, cold today, several factors, including unemploy high around 30. Clear, cold tonight, low manrijpatpr lEornittg Mrrali Area news ..1-2-B Week-Review .6B tonight from 7 to 9:30 at the recession in 1977 but Inflation will ease only slightly and ment in the area, the amount of jobs, slightly higher than the national in teens. Increasing cloudiness Satur Business.......14-A Editorial ......... 4-A average, but the region’s level is Manchester State Armory. unemployment will increase, an authoritative report said Churches .... 13-A Wings.......... 11-A created by the work, and the lasting Membership is open to all young peo day, a little warmer, high mid to upper ‘The Bright One” effect of the project on the communi slightly higher than Manchester. today. 30s, National weather forecast map on Classified ,. .610-B Family..........6A ple from Grade 7 through high The Organization for Economic Cooperation and TWENTY.EIGHT PAGES Comics........ ll-B Obituaries ... 14-A ty- Thus, it might have given the com Page 9-B. munity an ^ g e in consideration for school. More information may be ob Development, which guides the economies of the rich 'TWO SECTIONS MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, DECEMBER,24, 1976 - VOL. -

Skiing with Champions One Trip - Four Countries (Austria, Switzerland, Italy and France) and 20 Plus Villages!

Skiing with Champions One Trip - Four Countries (Austria, Switzerland, Italy and France) and 20 Plus Villages! Ischgl-Arlberg, Austria/Switzerland and Alta Badia, Italy Sunday, January 18 – Sunday 25, 2015 (Three Add-On Days) ~ Verbier, Switzerland / France Sunday, January 25 – Wednesday, January 28, 2015 Champion Ski Guides and Social Hosts Franz Klammer Franz Weber Olympic, World & World Cup Champion Olympian & 6x Consecutive 4x Hahnenkamm Winner DH World Speed Skiing Champion The Greatest Downhiller of All Time! Andre Arnold Stephan Keck 4x Overall World Pro Skiing Champion Extreme Mountain Climber, Nanga Parbat 8125m Nina Arnold (Andre’s daughter will also join) Shisha Pangma 8027m; GII 8045m Manaslu 8156m Christa Höllrigl Patrick Ortlieb World Champion – Powder Ski & Technical Skiing Olympic, World and World Cup DH Champion Karen Putzer Peter Runggaldier Olympian & World Champion Medallist Olympian, World & World Cup Champion Winner of 8 World Cup Races Heinz Holzer Ivo Rudiferia World Cup Super-G Champion Snowboard World & World Cup Champion Swiss Olympians and World Cup Champions & Hosts Martin Hangl, William Besse, Roland Colombin, Philippe Roux Planned Agenda Ischgl – Alta Badia 2015 with three add-on days in Verbier, Switzerland “Skiing with Champions” January 18 – 25, 2015 and January 25 – 28, 2015 Level of Ability Recommended: Low-Intermediate to Expert We can accommodate beginners with prior notice in order to hire qualified instructors. *Attire Recommendation: **T VIP Transportation *C: Casual, Warm Layers, Luxury Coach with Walk-In Humidor, Havana Room, Draft Outerwear, Gloves and Hats Beer and Fine Wines. Helicopter Transport. *S: Skiwear https://arlbergexpress.com/en/willkommen/ *ME: Mountain Elegant, Sports Coat, Business Casual Sunday Arrival at the Elizabeth Arthotel and Welcome Dinner January 18, 2015 Individual arrival to Ischgl from Zürich, Munich or Innsbruck. -

1 Doc. 8.4 (Rev.) CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN

Doc. 8.4 (Rev.) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Eighth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Kyoto (Japan), 2 to 13 March 1992 ADMISSION OF OBSERVERS Bodies and Agencies Applying for Observer Status 1. According to Article XI, paragraph 7, of the Convention, any body or agency technically qualified in protection, conservation or management of wild fauna and flora, in the following categories, which has informed the Secretariat of its desire to be represented at a meeting of the Conference by observers, shall be admitted unless at least one-third of the Parties present object: a) international agencies or bodies, either governmental or non-governmental, and national governmental agencies and bodies; and b) national non-governmental agencies or bodies which have been approved for this purpose by the State in which they are located. 2. Rule 2, paragraph 3, of the Rules of Procedure [Doc. 8.3 (Fin.)] requires that bodies and agencies desiring to be represented at the meeting by observers shall submit the names of these observers - and, in the case of bodies and agencies referred to in paragraph (2) (b) of this Rule, evidence of the approval of the State in which they are located - to the Secretariat of the Convention at least one month prior to the opening of the meeting. 3. These provisions apply to all agencies or bodies other than the United Nations and its Specialized Agencies (which are not subject to the admission procedure of Article XI, paragraph 7, of the Convention, according to paragraph 6 of the same Article, and Rule 2, paragraph 1, of the Rules of Procedure). -

The Octopus Mind and the Argument Against Farming It

Jacquet, Jennifer; Franks, Becca; and Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2019) The octopus mind and the argument against farming it. Animal Sentience 26(19) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1504 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2019.271: Jacquet, Franks & Godfrey-Smith on Mather on Octopus Mind The octopus mind and the argument against farming it Commentary on Mather on Octopus Mind Jennifer Jacquet Department of Environmental Studies New York University Becca Franks Department of Environmental Studies New York University Peter Godfrey-Smith Faculty of Science University of Sydney Abstract: Mather is convincing about octopuses having ‘a controlling mind, motivated to gather information,’ but stops short of asking what having that mind means for octopus moral standing. One consequence of understanding the octopus mind should be a refusal to subject octopuses to mass production. Octopus farming is in an experimental phase and supported by various countries. We argue that it is unethical because of concerns about animal welfare as well as environmental impacts. Jennifer Jacquet, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies at New York University and part of NYU Animal Studies, works on large-scale environmental problems, including overfishing, climate change, and the Internet wildlife trade. Website Becca Franks, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies at New York University, studies well-being and motivation, with a focus on aquatic animal welfare. -

Vol 12 Issue 1

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Michael E. Ryan Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Lloyd W. Newton Commander, Air University Lt Gen Joseph J. Redden Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Robert M. Hylton Editor Lt Col James W. Spencer Senior Editor Maj Michael J. Petersen Associate Editor Dr. Doris Sartor Professional Staff Hugh Richardson, Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant Joan Hickey, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director o f Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Mary P. Ferguson, Prepress Production Manager The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strat egy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be con strued as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air Ed ucation and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If they are reproduced, the Airpower Journal requests a courtesy line. JOURNAL Spring 1998______________________Volume XII, No. 1__________________ AfRP 10-1 In Search of High Ground: The Airpower Trinity and the Decisive Potential of Airpower............... 4 Lt Col David K. Edmonds. USAF FEATURES Transformational Leaders and Doctrine in an Age of Peace: Searching for a Tamer Billy M itchell.............. -

In Handbook for Decision Makers

ERS AK M ON ECISI D R O F ANDBOOK H Jochen Rehrl (ed.): Rehrl Jochen HANDBOOK FOR DECISION MAKERS THE COMMON SECURITY AND DEFENCE POLICY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION ISBN: 987-3-902275-35-6 HANDBOOK FOR DECISION MAKERS The COmmON SecUritY AND DefeNce POLicY OF the EUROpeAN UNION edited by Jochen Rehrl with forewords of H. E. Gerald Klug Federal Minister of Defence and Sports of the Republic of Austria H. E. Walter Stevens Chair of the Political and Security Committee General Patrick de Rousiers Chair of the European Union Military Committee Mika-Markus Leinonen Chair of the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management Disclaimer: Any views or opinions presented in this handbook are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the European Union or the Austrian Ministry of Defence and Sports. Imprint: Publication of the Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports of the Republic of Austria Editor: Jochen Rehrl Published by: Directorate for Security Policy of the Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports of the Republic of Austria Photos: Henny Ray Abrams, Etienne Ansotte, Austrian Armed Forces, Austrian Study Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution, Tashana Batista, Alexander Belousov, Thierry Chesnot, Council General Secretariat, Council of the EU, Council of the European Union, Fehim Demir, Christos Dogas, Earth Observatory of Singapore, EEAS, EEAS/EUBAM Moldova, EEAS/EUCAP NESTOR, EEAS/EULEX Kosovo, EEAS/EUNAVFOR Somalia, EEAS/EUTM Mali, Patricia Esteve, EU Council, EUFOR ALTHEA, EUFOR Tchad/ RCA, EULEX/Enisa Kasemi, European Communities, European Council, European External Action Service, European Space Agency, European Union, EUROPOL CORPS, EUROSUR HQ, Federal Ministry for European and Internnational Affairs of Austria, Frontex, Alain Grosclaude, ICC-CPI, Enisa Kassemi, Max Koot, Christian Lambiotte, Pedro Lareira, J.P. -

The Hundredth Anniversary of the Arrival in Detroit of the First Organized Immigration from Germany

The hundredth anniversary of the arrival in Detroit of the first organized immigration from Germany. [Detroit, Mich. : Neustadter Kirmess Committee, 1930]. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015071204260 Public Domain, Google-digitized http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-google We have determined this work to be in the public domain, meaning that it is not subject to copyright. Users are free to copy, use, and redistribute the work in part or in whole. It is possible that current copyright holders, heirs or the estate of the authors of individual portions of the work, such as illustrations or photographs, assert copyrights over these portions. Depending on the nature of subsequent use that is made, additional rights may need to be obtained independently of anything we can address. The digital images and OCR of this work were produced by Google, Inc. (indicated by a watermark on each page in the PageTurner). Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially. The images are provided for educational, scholarly, non-commercial purposes. 1830-/930 ilOCAlWIVEKSARV fiERMAM IMMWRATIOM TO DETROIT \J ^129 <s&$)®<s®®®®&s&^ 100th, Anniversary ®s®®®®®^s®®®<s^^ The Hundredth Anniversary of the arrival in Detroit of the First Organized Immigration from Germany Seal of Neustadt St. Martin dividing his garment with the poor man. The Mainzer Wheel denotes the rule of the Arch-Bishop Kurfuerst of Mainz, prior to 1802. Bentfey Historical Library IMv'<tpstv of Michigan ' ®®®?)®®®!sx£)®®®®®®®®®<s^ 1830 ' 1930 ®<s®®®®®®s®®s®®®&s&s^