What Motivated Teachers to Teach About the Soviet Union After World War Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1946, Volume 41, Issue No. 4

MHRYMnD CWAQAZIU^j MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE DECEMBER • 1946 t. IN 1900 Hutzler Brothers Co. annexed the building at 210 N. Howard Street. Most of the additional space was used for the expansion of existing de- partments, but a new shoe shop was installed on the third floor. It is interesting to note that the shoe department has now returned to its original location ... in a greatly expanded form. HUTZLER BPOTHERSe N\S/Vsc5S8M-lW MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE A Quarterly Volume XLI DECEMBER, 1946 Number 4 BALTIMORE AND THE CRISIS OF 1861 Introduction by CHARLES MCHENRY HOWARD » HE following letters, copies of letters, and other documents are from the papers of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (b. 1805, d. 1888). They are confined to a brief period of great excitement in Baltimore, viz, after the riot of April 19, 1861, when Federal troops were attacked by the mob while being marched through the City streets, up to May 13th of that year, when General Butler, with a large body of troops occupied Federal Hill, after which Baltimore was substantially under control of the 1 Some months before his death in 1942 the late Charles McHenry Howard (a grandson of Charles Howard, president of the Board of Police in 1861) placed the papers here printed in the Editor's hands for examination, and offered to write an introduction if the Committee on Publications found them acceptable for the Magazine. Owing to the extraordinary events related and the revelation of an episode unknown in Baltimore history, Mr. Howard's proposal was promptly accepted. -

Vision Document 2016 – 2025

AFRO-EURASIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, EDUCATION, DEVELOPMENT AND EMPOWERMENT (ACCEDE) Registered with the Government of Jammu and Kashmir as a Public Charitable Trust Dr. Ravi Jyee VISION DOCUMENT 2016 – 2025 AFRO-EURASIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, EDUCATION, DEVELOPMENT AND EMPOWERMENT Jammu 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION, PHILOSOPHY, ORIGINS AND ACTIVITIES The Afro-Eurasian Chamber of Commerce, Education, Development and Empowerment (ACCEDE) has been established with a view to conducting applied researches with benevolent philosophies with special reference to the functional areas related to, health, art, culture, education, literacy, labour, employability, skill development, micro, small and medium enterprises, rural development, poverty alleviation, science, technology, industrial development, management science, sports, urban development, vocationalisation, women’s empowerment, youth development etc. Established in the year 2015 as a Public Charitable Trust, the origins of this organization is based on the principles of benevolence as a non-political, non- governmental and non-profit making organizations dedicated for the cause of international development aimed at applied researches needed for ensuring the sustainable development of our society. Benevolence can be seen as optimism applied to other people and relationships. It does not consist of any particular set of actions, but a general good will towards others based on the benevolent universe premise: Successful trading relationships with others are the to be expected, so treat other people accordingly. For example, if you are optimistic about other people and relationships, then perhaps you will treat a stranger like you would normally treat an acquaintance and an acquaintance like a friend. This broadcasts a friendly, non-hostile, attitude and a willingness to trade which is a prerequisite for peaceful interaction. -

U.S. Senators: Vote YES on the Disability Treaty! © Nicolas Früh/Handicap International November 2013 Dear Senator

U.S. Senators: Vote YES on the Disability Treaty! © Nicolas Früh/Handicap International November 2013 Dear Senator, The United States of America has always been a leader of the rights of people with disabilities. Our country created the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), ensuring the rights of 57.8 million Americans with disabilities, including 5.5 million veterans. The ADA inspired the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) treaty. The CRPD ensures that the basic rights we enjoy, such as the right to work and be healthy, are extended to all people with disabilities. Last December, America’s leadership diminished when the Senate failed to ratify the CRPD by 5 votes. In the pages that follow, you will find the names of 67,050 Americans who want you to vote Yes on the CRPD. Their support is matched by more than 800 U.S. organizations, including disability, civil rights, veterans’ and faith-based organizations. These Americans know the truth: • Ratification furthers U.S. leadership in upholding, championing and protecting the rights of children and adults with disabilities • Ratification benefits all citizens working, studying, or traveling overseas • Ratification creates the opportunity for American businesses and innovations to reach international markets • Ratification does not require changes to any U.S. laws • Ratification does not jeopardize U.S. sovereignty The Senate has an opportunity that doesn’t come along often in Washington—a second chance to do the right thing and to ratify the CRPD. We urge you and your fellow Senators to support the disability treaty with a Yes vote when it comes to the floor.We must show the world that U.S. -

Bulletin 160501 (PDF)

RAO BULLETIN 1 May 2016 PDF Edition THIS BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject * DOD * . 04 == Stars and Stripes [01] -------------- (May Be Silenced by Funding Cuts) 05 == DoD Religious Expression [04] ---------- (U.S. Court of Appeals Case) 07 == Commissary Prices [04] ------- (Draft Bill Eliminates At-Cost Pricing) 08 == Selective Service System [17] --- (May be Headed for the Scrap Heap) 09 == Selective Service System [18] -------- (HASC | Women Must Register) 09 == BRAC [47] ------------ (DoD Sends Congress Excess Capacity Report) 10 == BRAC [48] -------------------- (Pentagon May Start Unilateral Closures) 11 == BRAC [49] --------------- (HASC Democrat Seeks Base Closures Law) 12 == Toxic Exposure | Wurtsmith AFB ------------------ (PFC Tainted Water) 15 == State Sponsored Terrorism ----------- (State Linked to Act can be Sued) 16 == Arlington National Cemetery [58] --- (38 Acre Expansion Assessment) 17 == POW/MIA [72] ----------------- (North Korea Hands Over 17 Remains) 18 == POW/MIA Recoveries ------------------ (Reported 16 thru 30 Apr 2016) * VA * . 21 == VA Prosthetics [14] -------- (A Giant Step for Veteran Amputees | POP) 22 == VA Appeals [23] ------------------ (COA Rules in Favor of Staab | $48k) 24 == VA Commission on Care [04] -- (VA Leadership Updates Commission) 25 == VA Commission on Care [05] ----- (MOAA | Fix, Don’t Dismantle VA) 26 == VA Privatization [03] ---------------- (Evidence Does Not Support Need) 27 == VA Medical Marijuana [19] --------------- (DEA Approves PTSD Study) 28 == VA Women -

Germany, Afghanistan, and the Process of Decision Making in German Foreign Policy: Constructing a Framework for Analysis

ABSTRACT Title of Document: GERMANY, AFGHANISTAN, AND THE PROCESS OF DECISION MAKING IN GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY: CONSTRUCTING A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS Karin L. Johnston, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor George Quester, Department of Government and Politics Germany’s emerging role as a supplier of security by contributing troops to out-of-area operations is a significant change in post-unification German foreign and security policy, and yet few studies have sought to explain how the process of decision making also has changed in order to accommodate the external and domestic factors that shape policy preferences and outcomes. The dissertation addresses these theoretical gaps in foreign policy analysis and in German foreign and security policy studies by examining the decision-making process in the case of Afghanistan from 2001–2008, emphasizing the importance of institutional structures that enable and constrain decision-makers and then gathering the empirical evidence to construct a framework for analyzing German foreign policy decision making. The dynamics of decision-making at the state level are examined by hypothesizing about the role of the chancellor in the decision-making process— whether there has been an expansion of chancellorial power relative to other actors— and about the role of coalition politics and the relative influence of the junior coalition partner in coalition governments. Results indicate that there are few signs that federal chancellors dominate or otherwise control decision-making outcomes, and that coalition politics remain a strong explanatory factor in the process that shapes the parameters of policy choices. The dissertation highlights the central role of the Bundestag, the German parliament. -

Die Befreiung Innsbrucks 1945.Pdf (0.9

Einen zweiten, den wir aufanden, führte ich auch zurück. Auf dem Weg warfen sie Koppel, Gasmaske und Stahlhelm weg, weinten und sagten, sie möchten heim, einer nach Klagenfurt, der andere nach Steiermark.«293 Die Kämpfe in Zirl und am Zirler Berg forderten den Tod von fünf deutschen Soldaten, drei felen einem Autounfall zum Opfer. Drei US-Soldaten starben am Zirler Berg, acht bis zehn weitere, als der Krieg praktisch bereits aus war. Am 7. Mai fuhren sie am Zirler Berg auf eine Mine.294 In den frühen Morgenstunden des 4. Mai verließ der Sonderverband »Task Force May« des 410. Regiments Telfs und rückte an der südlichen Tal- seite über die bisher noch unbesetzten Dörfer Oberhofen, Flaurling, Hatting usw. nach Innsbruck vor.295 INNSBRUCK Das Umfeld, um Widerstand zu leisten, war in Tirol während der gesam- ten Herrschaf des Nationalsozialismus mehr als ungünstig. Die Bevölke- rung stand ihm reserviert gegenüber, die katholische Kirche lehnte politi- schen Widerstand ab. Sie war die einzige große, vom Nationalsozialismus unabhängige Institution, die den März 1938 überstanden hatte. Und sie übte weiterhin beachtlichen Einfuss auf die Menschen aus. Ein großer Teil ernstzunehmender Konfikte zwischen Regime und Bevölkerung betraf den Kulturkampf der Nationalsozialisten gegen die katholische Kirche. In zwei Gauen waren die Gläubigen und ihre geistlichen Führer am nachhaltigsten bedrängt: in Kärnten, dem Osttirol angegliedert war, und Tirol-Vorarlberg. Die Gauleiter Rainer und Hofer fuhren den antiklerikalsten Kurs im Deut- schen Reich. Hofer pfegte noch dazu eine persönliche Feindschaf gegen den jungen Bischof Paulus Rusch, da er sich bei dessen Ernennung über- gangen gefühlt hatte. Der Gauleiter sah sich als Landesfürst und glaubte, in seinem Machtbereich ein Mitspracherecht bei der Bestellung eines Bischofs zu haben, zumindest wollte er in den Bestellungsprozess miteinbezogen wer- den. -

GSI Newsletter May 2016

[email protected] [email protected] www.genshoah.org Generations of the Shoah International Newsletter May, 2016 Dear Members and Friends, GSI mourns the passing of Frederick Mayer, the German-Jewish refugee-turned-spy. Mayer was the last surviving member of OSS Operation Greenup, one of the most successful American espionage operations during World War II. Impersonating a German officer in Austria, Mayer was able to gain critical information on the movement of 26 trains en route to the Italian front via the Brenner Pass. The Allies were able to destroy that entire transport and for this Eisenhower credited Mayer with shortening the war by six months. However, the Germans realized there was a spy and Mayer got picked up by the Gestapo. Despite being tortured he never disclosed the location of his team. While a prisoner, Mayer convinced the Gaulieter (leader) of Innsbruck to surrender and crossed battle lines to bring those terms to the Allies. No civilian lives were lost. For this Mayer was awarded the Order of the Tyrolean Eagle which honors people who are of particular political, economic or cultural importance for the Tyrolean state. For more on Fred Mayer, see the articles and video in the FYI section below. We have a list of Yom Hashoah V’Hagvurah commemorative events below. Please remember there are survivors in need and your financial support to your local Jewish Social Service agency can go a long way. Also, there are memorials and museums in your communities that could benefit from your donations. As always, if you feel well served by GSI please pass it forward and give generously to the institution of your choice. -

Vol 12 Issue 1

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Michael E. Ryan Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Lloyd W. Newton Commander, Air University Lt Gen Joseph J. Redden Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Robert M. Hylton Editor Lt Col James W. Spencer Senior Editor Maj Michael J. Petersen Associate Editor Dr. Doris Sartor Professional Staff Hugh Richardson, Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant Joan Hickey, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director o f Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Mary P. Ferguson, Prepress Production Manager The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strat egy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be con strued as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air Ed ucation and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If they are reproduced, the Airpower Journal requests a courtesy line. JOURNAL Spring 1998______________________Volume XII, No. 1__________________ AfRP 10-1 In Search of High Ground: The Airpower Trinity and the Decisive Potential of Airpower............... 4 Lt Col David K. Edmonds. USAF FEATURES Transformational Leaders and Doctrine in an Age of Peace: Searching for a Tamer Billy M itchell.............. -

Operation Greenup!

Cold Open: Operation Greenup! An operation carried out by a special group of men many have called the “real life Inglorious Basterds,” a reference to the 2009 Quentin Tarantino film in which a group of US Jewish soldiers plot to assassinate high-up Nazi leaders. Operation Greenup wasn’t EXACTLY like the Hollywood blockbuster. No one was catching Nazis and carving swastikas into their foreheads., Hitler doesn’t get sub-machine gunned down in a burning theater that also gets blown up - gotta love Tarantino’s over-the-top death sequences. There was no assassination plan. BUT - a lot of daring, cinematic, and incredibly courageous moments did go down. There WAS a cast of characters that feel more like Hollywood creations than real people. It WAS an amazing, high risk, high stakes operation that did truly involve some Jewish men risking their lives, parachuting in behind enemy lines to quote “Kill some nazis.” They may not have been pulling off executions in the woods, but they did help give the Allies valuable intel that saved a whole bunch of lives. The short version of their story is this: two Jewish refugees to the United States, living in Brooklyn - Frederick Mayer, 23, and Hans Wynberg, 22, end up in the Office of Strategic Services - the OSS - forerunner to the CIA, and parachute deep behind Nazi lines into the Austrian province of Tyrol [ ti-roll] in February of 1945. Their mission: to compile reports on German rail traffic over the Brenner Pass between Italy and Austria. And make sure the German’s don’t havea. -

Bulletin of Nicholas School of the Environment 2019-2020

Bulletin of Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment 2019-2020 Bulletin of Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment 2019-2020 Duke University Registrar Frank Blalark, Associate Vice Provost and University Registrar Academic Liaisons Cynthia A. Peters and Denise Haviland Coordinating Editor Bahar Rostami Publications Coordinator Keely Fagan Photographs Cover photo: Tianyu Wang, MEM’16 Courtesy of Nicholas School of the Environment and Duke University (Bill Snead, Megan Mendenhall, Les Todd, Jared Lazarus, Joseph Fader, SP Murray Photography, and Chris Hildreth) The information in this bulletin applies to the academic year 2019-2020 and is accurate and current, to the greatest extent possible, as of September 2019. The university reserves the right to change programs of study, academic requirements, teaching staff, the calendar, and other matters described herein without prior notice, in accordance with established procedures. Duke University does not tolerate discrimination or harassment of any kind. Duke University has designated the Vice President for Institutional Equity as the individual responsible for the coordination and administration of its nondiscrimination and harassment policies generally. The Office for Institutional Equity is located in Smith Warehouse, 114 S. Buchanan Blvd., Bay 8, Durham, NC 27708, (919) 684- 8222, [email protected]. Sexual harassment and sexual misconduct are forms of sex discrimination and prohibited by the university. Duke University has designated Jayne Grandes as its director of Title IX compliance and Age Discrimination Act coordinator. She is also with the Office for Institutional Equity and can be contacted at (919) 660-5766 or [email protected]. Questions or comments about discrimination, harassment, domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking can be directed to the Office for Institutional Equity, (919) 684-8222. -

Dropzone Issue 1

HARRIN GTON AVIAT ION MUSE UMS HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS THE DROP ZONE V OLUME 11 I SSUE 1 THE DROP ZONE S UMMER 2013 Editor/Publisher: Fred West INSIDE THIS ISSUE: American Hero 4 Welcome to the Birthday Edition of Obituary 5 The Drop Zone On the weekend of the 31st August 2013, there will be celebra- Modern Naviga- 5 tions to commemorate the opening in 1993 of the Carpetbagger tion museum. The opening ceremony was conducted by the late Colonel R.W. Fish. Editorial 7 During the weekend there will be various activities for visitors Awards from 7 and admission to the museum will be free. After the museum French Ambas- closes on Saturday 31st August, there will be a hog roast feast sador for all members of the museum society. Details have been sent Aviation Quiz 1 10 to members and associates. Aviation Quiz 2 11 SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: Awards for ‘forgotten heroes’ Flying without a pilot Aviation quiz To celebrate the museum’s 20th birthday and the 70th anniver- sary of the formation of The Carpetbaggers, we have commis- sioned a new tea towel that is on sale in the museum gift shop. P AGE 2 V OLUME 11 I SSUE 1 Photographs of former Commanding Officers and Squadron Commanders of the 801st/492nd Bomb Group are now displayed in the museum canteen. THE DROP ZONE P AGE 3 P AGE 4 V OLUME 11 I SSUE 1 Frederick Mayer is a True lost to history. American Hero It’s a thrilling tale. After parachuting into Austria in 1945, Fred spent months organizing By United States Senator Jay Rocke- elements of the anti-Nazi resistance; collecting feller vital intelligence about German troop move- ments; spying on war factories and infrastruc- A young boy is born to a Jewish fam- ture; and even tracking the whereabouts of Mus- ily in Germany. -

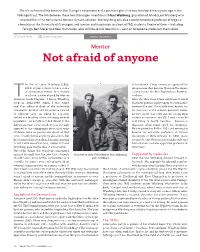

Not Afraid of Anyone

There’s a chemical link between Ben Feringa’s nanomotor and a puncture glue that was developed many years ago in the Folkingestraat. The link between these two Groningen inventions is Hans Wijnberg, grandson of Jehuda Levi Wijnberg who invented the in the Netherlands famous ‘Simson solution’. But Wijnberg was also a world-renowned professor of organic chemistry at the University of Groningen, and mentor and inspiration to a host of PhD students. Twelve of them – including Feringa, Bert Meijer and Kees Hummelen, who still like to talk about him – went on to become professors themselves. KIRSTEN OTTEN ELMER SPAARGAREN FERINGA AND MENTOR Mentor Not afraid of anyone he life of Hans Wijnberg (1922- of Innsbruck. These events so captured the 2011) seems to have been a series imagination that director Quentin Tarantino of spectacular events. It is worthy loosely based his film Inglourious Basterds T of a book, a view shared by History on them. alumnus Luuk Hajema: ‘I knew Wijnberg After the liberation, Hans and Louis learned back in 1984-1989, when I was editor that their parents and younger brother hadn’t and then editor-in-chief of the university survived the war. The family firm, known for newspaper. At that time he wrote a column its invention of the Simson puncture repair ‘A different view’, in which he regularly kit (see inset), was sold and the young men ruffled the feathers of the left-wing student decided to return to the US. Louis – now 94 population. As a right-minded liberal in the and living in North Carolina – became a American sense of the word, he was strongly physicist, while Hans opted for chemistry.