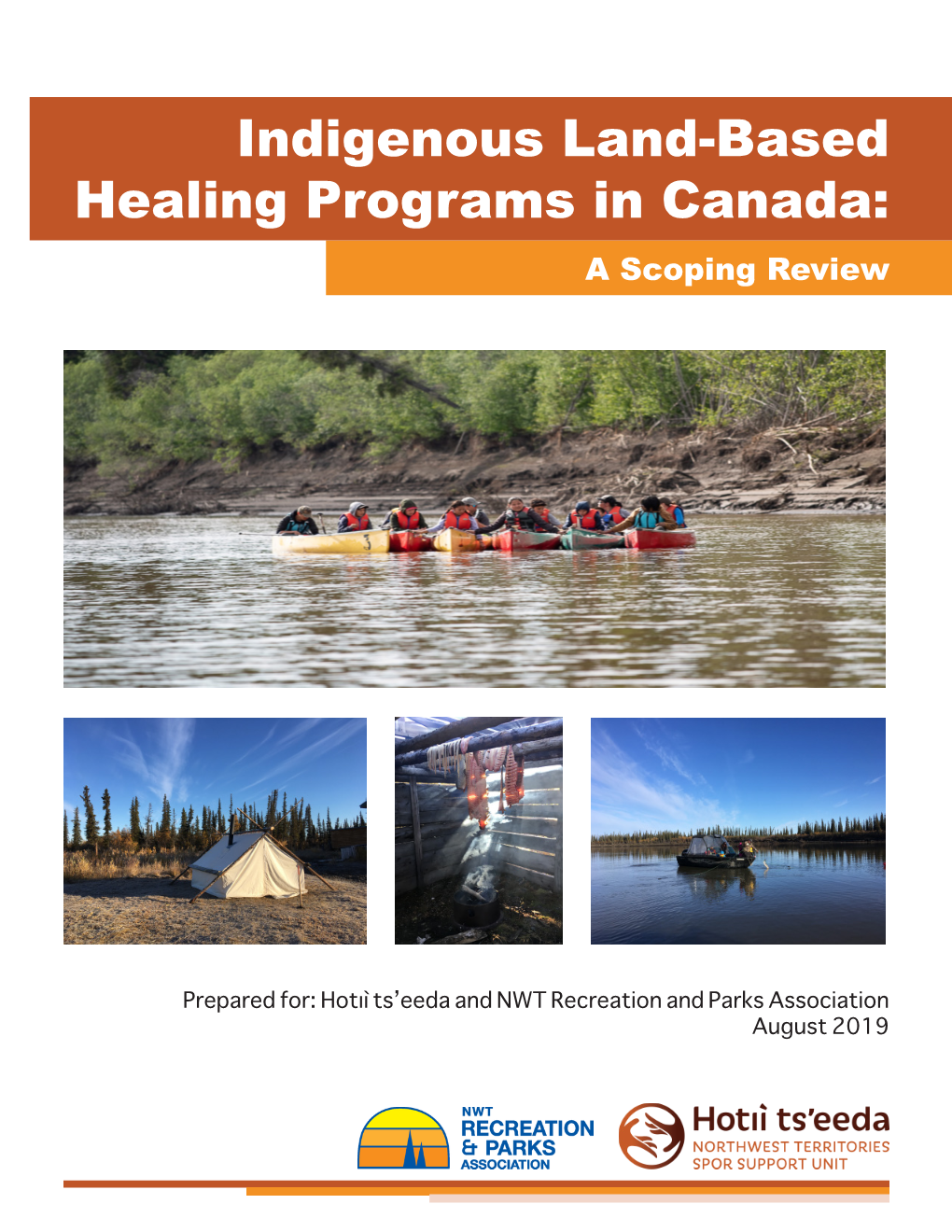

Indigenous Land-Based Healing Programs in Canada: a Scoping Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Native

To conduct a simple search of the many GENERAL records of Alaska’ Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog use the search term Alaska Native. To search specific areas or villages see indexes and information below. Alaska Native Villages by Name A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Alaska is home to 229 federally recognized Alaska Native Villages located across a wide geographic area, whose records are as diverse as the people themselves. Customs, culture, artwork, and native language often differ dramatically from one community to another. Some are nestled within large communities while others are small and remote. Some are urbanized while others practice subsistence living. Still, there are fundamental relationships that have endured for thousands of years. One approach to understanding links between Alaska Native communities is to group them by language. This helps the student or researcher to locate related communities in a way not possible by other means. It also helps to define geographic areas in the huge expanse that is Alaska. For a map of Alaska Native language areas, see the generalized map of Alaska Native Language Areas produced by the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. Click on a specific language below to see Alaska federally recognized communities identified with each language. Alaska Native Language Groups (click to access associated Alaska Native Villages) Athabascan Eyak Tlingit Aleut Eskimo Haida Tsimshian Communities Ahtna Inupiaq with Mixed Deg Hit’an Nanamiut Language Dena’ina (Tanaina) -

Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts

Indigenous Tongues: Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts A Policy Paper for the National Indian Health Board Authored by: Keixe Yaxti/Maka Monture Of the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe of Alaska & Six Nations Mohawk of Canada Image 1: “Dig your paddle Deep” by Maka Monture Contents Introduction 2 Background on Tlingit Language 2 Health in Indigenous Languages 2 How Language Efforts Can be Developed 3 Where The State is Now 3 Closing Statement 4 References 4 Appendix I: Supporting Document: Tlingit Human Diagram 5 Appendix II: Supporting Document: Yakutat Tlingit Tribe Resolution 6 Appendix III: Supporting Document: House Concurrent Resolution 19 8 1 Introduction There is a dire need for native language education for the preservation of the Southeastern Alaskan Tlingit language, and Alaskan Tlingit Tribes must prioritize language restoration as the a priority of the tribe for the purpose of revitalizing and perpetuating the aboriginal language of their ancestors. According to the Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council, not only are a majority of the 20 recognized Alaska Native languages in danger of being lost at the end of this century, direct action is needed at tribal levels in Alaska. The following policy paper states why Alaskan Tlingit Tribes and The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, a tribal government representing over 30,000 Tlingit and Haida Indians worldwide and a sovereign entity that has a government to government relationship with the United States, must take actions to declare a state of emergency for the Tlingit Language and allocate resources for saving the Tlingit language through education programs. -

104 Alaska Journal of Anthropology Volume 3, Number 1 Cabin Door At

Cabin door at Ft. Egbert, Eagle, Alaska, 1983. © R. Drozda. 104 Alaska Journal of Anthropology Volume 3, Number 1 LANGUAGE WORK IN A LASKAN A THABASCAN A ND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO ALASKAN ANTHROPOLOGY James Kari Professor of Linguistics Emeritus, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Dena’inaq’ Titaztunt, 1089 Bruhn Rd., Fairbanks AK 99709. [email protected] Abstract: This paper provides context on my 30-plus years of work with Alaska Athabascan languages. I discuss features of my research program in Athabascan that relate to anthropology, emphasizing the two languages I have spent the most time with, Dena’ina and Ahtna, and four research areas: lexicography, narrative, ethnogeography, and prehistory. I conclude with some observations on the prospects for Alaska Athabascan research. Keywords: Athabascan language research, Ethnogeography, Dena’ina prehistory INTRODUCTION I first came to Alaska in May of 1972 when I spent Language work, as I wrote in a 1991 article for the Tanana two weeks in Kenai doing linguistic field work on Chiefs Conference’s Council, embraces the array of goals Dena’ina. At the first meeting of the Alaska Anthropo- and methods that I employ, and the term is valid and un- logical Association (aaa) in March of 1974 I gave a pa- derstandable in communities where I have long-term re- per on Dena’ina dialects. I have been a regular partici- lationships with expert speakers. pant at aaa meetings, and this is my favorite annual con- ference. I first became interested in Athabascan research when I was a high school teacher on the Hoopa Reser- I have been engaged in long-term documentation on vation in Northern California in 1969-70. -

CURRICULUM VITAE for JAMES KARI September, 2018

1 CURRICULUM VITAE FOR JAMES KARI September, 2018 BIOGRAPHICAL James M. Kari Business address: Dena=inaq= Titaztunt 1089 Bruhn Rd. Fairbanks, AK 99709 E-mail: [email protected] Federal DUNS number: 189991792, Alaska Business License No. 982354 EDUCATION Ph.D., University of New Mexico (Curriculum & Instruction and Linguistics), 1973 Doctoral dissertation: Navajo Verb Prefix Phonology (diss. advisors: Stanley Newman, Bruce Rigsby, Robert Young, Ken Hale; 1976 Garland Press book, regularly used as text on Navajo linguistics at several universities) M.A.T., Reed College (Teaching English), 1969 U. S. Peace Corps, Teacher of English as a Foreign Language, Bafra Lisesi, Bafra, Turkey, 1966-68 B.A., University of California at Los Angeles (English), 1966 Professional certification: general secondary teaching credential (English) in California and Oregon Languages: Field work: Navajo (1970), Dena'ina (1972), Ahtna (1973), Deg Hit=an (Ingalik) (1974), Holikachuk (1975), Babine-Witsu Wit'en (1975), Koyukon (1977), Lower Tanana (1980), Tanacross (1983), Upper Tanana (1985), Middle Tanana (1990) Speaking: Dena’ina, Ahtna, Lower Tanana; some Turkish EMPLOYMENT Research consultant on Dene languages and resource materials, business name Dena’inaq’ Titaztunt, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1993-97 Associate Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1982-1993 Assistant Professor -

Ahtna Heritage Dancers Perform at the Quyana Alaska Annual Celebration of Dance

SHERMAN HOGUE / EXPLORE FAIRBANKS EXPLORE / HOGUE SHERMAN AHTNA HERITAGE DANCERS perform at the Quyana Alaska annual celebration of dance. Drum Beat Alaska Natives bring unique energy to performance arts BY ERIC LUCAS MES MISHLER MES A RK J RK A CL or many generations Iñupiaq mothers in at midwinter’s Festival of Native Arts in Fairbanks, thrum- Kaktovik, Alaska, have sung a calming lullaby to ming out a centuries-old song-tale about whale hunting. They might be Athabascan fiddlers whose reels and waltzes their babies that goes, roughly, añaŋa aa añaŋa reflect an art their ancestors adopted from Hudson’s Bay aa añaŋa aa aa aa. Such singing is called qunu, Company agents almost two centuries ago. They might be and it may be thousands of years old. Tlingit village residents showcasing a drum-and-spoken- word allegory about romance between disparate cultures. Allison Warden is an Anchorage-based performance f They might be Alutiiq performers whose guitar-led perfor- artist whose heritage traces back to Kaktovik, on Alaska’s mances meld Russian folk songs and ancient dances North Slope Arctic shore; she fondly remembers her grand- depicting seagull courtship. And they might be members of a modern recording group, Pamyua, performing at the mother singing qunu to her. So Warden has incorporated Anchorage Museum, whose danceable world music blends the line into one of her songs, Ancestor from the Future, an Yup'ik, Inuit, pop and African rhythms. engaging and thought-provoking piece that challenges The ingredients for these types of performances include young people to choose lives with purpose. -

March/April 2016

March-April 2016 Vol. XLVIII, No. 2 IN THIS ALASKA NATIVE LANGUAGES GO DIGITAL ISSUE How Digital Publishing Empowers Teachers, Connects Native Students Pg. 4 To Their Culture, and Supercharges Language Immersion Programs The Role of Digital by Steve Nelson Learning in a Modern School During the fi nal days of the 2014 session, the Alaska Leg- urgency has sparked statewide e orts to preserve Native System islature enacted House Bill 216, which designated twenty languages and make them more accessible to younger Alaska Native languages as o cial languages of the state. generations. In addition to English, Inupiaq, Siberian Yupik, Central Each of Alaska’s indigenous languages are direct refl ec- Pg. 5 Alaskan Yup'ik, Alutiiq, Unanga, Dena'ina, Deg Xinag, tions of the people who speak them, and serve as a kind of From the President: Holikachuk, Koyukon, Upper Kuskokwim, Gwich'in, Ta- verbal encyclopedia of regional information. Words, phras- nana, Upper Tanana, Tanacross, Hän, Ahtna, Eyak, Tlingit, ing and descriptive nuances convey a depth of knowledge Sharing Your Story Haida, and Tsimshian are now o cially recognized Alaska about the area where a language is spoken, as well as the languages. collective experiences of those who have inhabited it for many generations. is legislative action was profoundly signifi cant to the Pg. 5 Alaska Native population. As a Native elder once told me, “Our language IS our From the Executive culture.” Director: The Road Language Revitalization to Better Endings Regional stories and legends, passed orally from adults to All languages are fl uid and ever-changing, requiring new youth, were designed to teach important lessons about speakers to perpetuate their evolution. -

REGIONAL SUBSISTENCE BIBLIOGRAPHY Volume II Interior Alaska Number 1 ,, I Ii >$K,“‘,.! 1’ ‘R: :;’ ,‘;Si,‘!,L,L :J,~

,’ I I REGIONAL SUBSISTENCE BIBLIOGRAPHY Volume II Interior Alaska Number 1 ,, I ii >$k,“‘,.! 1’ ‘r: :;’ ,‘;Si,‘!,l,l :j,~,,,. I IIWAIY~ St ,; /#:!I ::,c:,.:;*: 1; i, $!‘I(p ,, ” 1.I I~,J/ ., .Lf, /:, ‘I! ,, 2.’ /’ , ‘,‘< ‘.: \fl:),,~q DIVISION OF SUBSISTENCE ALASKA DEPARTMENTOF FISH AND GAME TECHNICAL PAPER NO. 2 JUNEAU, ALASKA ANTHROPOLOGYAND HISTORIC PRESERVATION COOPERATIVE PARK STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS, ALASKA 1983 cover drawing by Tim Sczawinski CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS,,,..................................... V INTRODUCTION........................................... vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................. xvii INTERIOR REGIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................... ...3 KEYWORDINDEX .......................................... 133 AUTHOR INDEX ........................................... 151 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like first to extend sincere thanks to several members of the Division of Subsistence who have been instrumental in the ' establishment and perpetuation of the statewide subsistence bib1 iography project. They are Zorro Bradley, Richard Caulfield, Linda Ellanna, Dennis Kelso, and Sverre Pedersen. Each has contributed significantly with ideas, funding, and enthusiastic support for the project from its beginning. Second, special recognition is due to those who have worked with me to make this particular publication a reality. I would like to thank Elizabeth Andrews for her interest in the project, expert advice on reference sources and time spent reviewing publication drafts. Yer knowledge of northern Athabaskan literature was extremely helpful. The professional library of Richard Caulfield was a valuable source of reference material for this publication. I thank Rick also for his consistent support, helpful comments, and suggestions on publication drafts. Dr. Robert Wolfe provided organizational ideas and encouragement for which I am grateful. The University of Alaska Cooperative Park Studies Unit provided expert editorial and graphics support. -

Do Alaska Native People Get “Free” Medical Care?...78

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they paid in advance. Read more inside. UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY Holikachuk Unangax (Aleut) Han Inupiaq Alutiiq Tanacross Athabascan Haida (Lower) Tanana Siberian Yupik / St. Lawrence Island Upper Tanana Tsimshian Tlingit Yupik Deg Xinag (Deg Hit’an) Ahtna Central Yup’ik Koyukon Dena’ina (Tanaina) Eyak Gwich'in Upper Kuskokwim DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they traded land for it. See page 78. Libby Roderick, Editor UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 2008-09 BOOKS OF THE YEAR COMPANION READER Copyright © 2008 by the University of Alaska Anchorage and Alaska Pacific University Published by: University of Alaska Anchorage Fran Ulmer, Chancellor 3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, AK 99508 Alaska Pacific University Douglas North, President 4101 University Drive Anchorage, AK 99508 Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the editors, contributors, and publishers have made their best efforts in preparing this volume, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents. This book is intended as a basic introduction to some very complicated and highly charged questions. Many of the topics are controversial, and all views may not be represented. Interested readers are encouraged to access supplemental readings for a more complete picture. This project is supported in part by a grant from the Alaska Humanities Forum and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency. -

Download Date 05/10/2021 22:16:27

Deg Xinag Oral Traditions: Reconnecting Indigenous Language And Education Through Traditional Narratives Item Type Thesis Authors Leonard, Beth R. Download date 05/10/2021 22:16:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8930 DEG XINAG ORAL TRADITIONS: RECONNECTING INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION THROUGH TRADITIONAL NARRATIVES A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Beth R. Leonard, B.A., M.Ed. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3286620 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3286620 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. DEG XINAG ORAL TRADITIONS: RECONNECTING INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION THROUGH TRADITIONAL NARRATIVES by Beth R. Leonard RECOMMENDED: .. Advisory) Committee Chair <0> Chair, Cross-Cultural Studies APPROVED: Dean, College of Liberal Arts Dean of the Graduate School Date 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Dena'ina Noun Dictionary

Alaska Athabascan stellar astronomy Item Type Thesis Authors Cannon, Christopher M. Download date 28/09/2021 20:20:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/4817 ALASKA ATHABASCAN STELLAR ASTRONOMY A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Christopher M. Cannon, B.S. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2014 © 2014 Christopher M. Cannon Abstract Stellar astronomy is a fundamental component of Alaska Athabascan cultures that facilitates time-reckoning, navigation, weather forecasting, and cosmology. Evidence from the linguistic record suggests that a group of stars corresponding to the Big Dipper is the only widely attested constellation across the Northern Athabascan languages. However, instruction from expert Athabascan consultants shows that the correlation of these names with the Big Dipper is only partial. In Alaska Gwich’in, Ahtna, and Upper Tanana languages the Big Dipper is identified as one part of a much larger circumpolar humanoid constellation that spans more than 133 degrees across the sky. The Big Dipper is identified as a tail, while the other remaining asterisms within the humanoid constellation are named using other body part terms. The concept of a whole-sky humanoid constellation provides a single unifying system for mapping the night sky, and the reliance on body-part metaphors renders the system highly mnemonic. By recognizing one part of the constellation the stargazer is immediately able to identify the remaining parts based on an existing mental map of the human body. The circumpolar position of a whole-sky constellation yields a highly functional system that facilitates both navigation and time-reckoning in the subarctic. -

Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic Countries

Aleut previously Ainu Ainu previously Aleut Aleut Ainu previously Ainu Kamchadal Taz Even Orochi Udege Itelmen Orok Alutiiq Koryak Ulchi Nanai Nivkh Negi- Central Koryak dal Alaskan Kerek Yup'ik Chukchi Alyutor Haida Alutiiq Evenk Nootka Siberian Dena’ina Yup'ik Chuvan Eyak Tanacross Even Even Kwakiutl ALASKA Tlingit Ahtna Upper Tsimshian Kuskokwim Chukchi Yukagir Upper Tanana Iñupiat Tsetsaut Evenk Salish Carrier Tuchone Tanana Deg Tahltan Tlingit Hit'an Babine Holikachuk Sakha Tagish (Yakut) Sekani Hän Koyukon Iñupiat Yukagir R Sarsi Blackfoot Gwich'in Sakha Evenk Kaska Even (Yakut) U Southern Beaver Bear Northern Slavey Buryat A Atsina Lake Slavey S A Inuvialuit S Dogrib Assiniboine Buryat S Evenk I Yellowknife Evenk Soyot Cree D A Chip ewyan Buryat Inuit N Tofa Tuvinians U A Dolgan Tuvinian- Cree Todzhin Inuit Nga- Evenk nasan F N Tuvinians Khakas Chelkan Ket Ket E Chulym Cree Enets Shor Telengit Tuba A Teleut D Kuman- Altai NUNAVUT Selkup din Ojibwa Cree C Kalaallit SelE kup Nenets Nenets Inuit KhantR Haudeno- Algonkin Inuit saunee o Khant Huron Cree 80 A Nenets Mansi T Haudeno- Izhma- Komi I saunee Montagnais- GREENLAND Komi Naskapi Kalaallit O Kalaallit Komi- Naskapi Komi PermyaksN Abnaki Saami o Kalaallit 70 Karelians Saami Karelians Beothuk ICELAND FIN- Vepsians LAND FAROE Saami ISLANDS Faroese NORWAY 60o SWEDEN DENMARK 50o Indigenous peoples of the Arctic countries Subdivision according to language families Eskimo-Aleut family Notes: Na'Dene family Inuit group of Eskimo branch For the USA, only peoples in the State of Alaska are shown. For the Russian Federation, only peoples of the North, Siberia and Far East are shown. -

Upper Tanana Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Wrangell St. Elias National Park and Preserve

Technical Paper No. 325 Upper Tanana Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Wrangell St. Elias National Park and Preserve by Terry L. Haynes and William E. Simeone July 2007 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright © common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. correlation coefficient nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp.