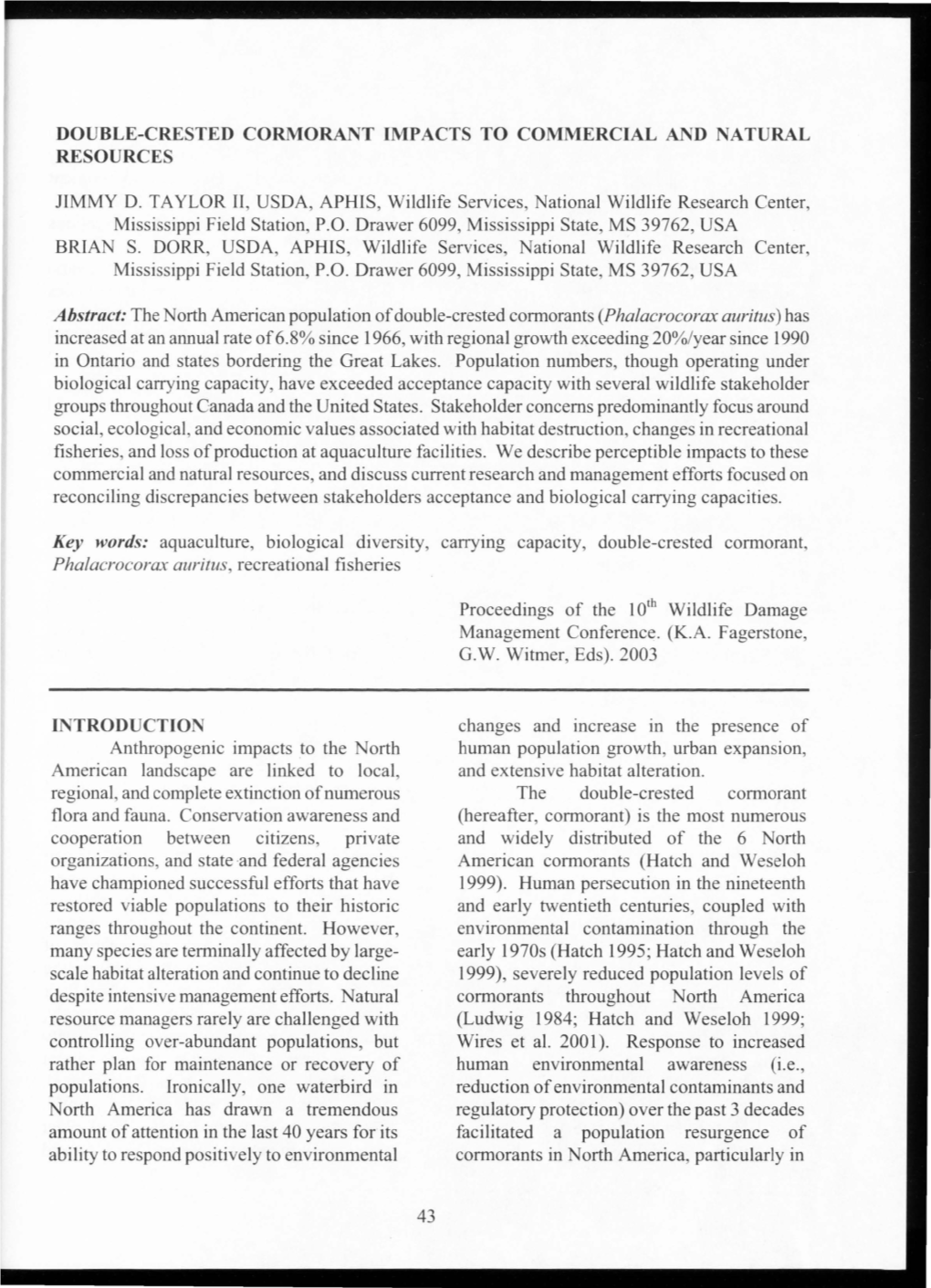

Double-Crested Cormorant Impacts to Commercial and Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niche Overlap Among Anglers, Fishers and Cormorants and Their Removals

Fisheries Research 238 (2021) 105894 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/®shres Niche overlap among anglers, fishersand cormorants and their removals of fish biomass: A case from brackish lagoon ecosystems in the southern Baltic Sea Robert Arlinghaus a,b,*, Jorrit Lucas b, Marc Simon Weltersbach c, Dieter Komle¨ a, Helmut M. Winkler d, Carsten Riepe a,c, Carsten Kühn e, Harry V. Strehlow c a Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587, Berlin, Germany b Division of Integrative Fisheries Management, Faculty of Life Sciences, Humboldt-Universitat¨ zu Berlin, Invalidenstrasse 42, 10115, Berlin, Germany c Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries, Alter Hafen Süd 2, 18069, Rostock, Germany d General and Specific Zoology, Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany e Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries, Institute of Fisheries, Fischerweg 408, 18069, Rostock, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Handled by Steven X. Cadrin We used time series, diet studies and angler surveys to examine the potential for conflict in brackish lagoon fisheries of the southern Baltic Sea in Germany, specifically focusing on interactions among commercial and Keywords: recreational fisheries as well as fisheries and cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis). For the time period Fish-eating wildlife between 2011 and 2015, commercial fisheries were responsible for the largest total fish biomass extraction Commercial fisheries (5,300 t per year), followed by cormorants (2,394 t per year) and recreational fishers (966 t per year). Com Human dimensions mercial fishing dominated the removals of most marine and diadromous fish, specifically herring (Clupea Conflicts Recreational fisheries harengus), while cormorants dominated the biomass extraction of smaller-bodied coastal freshwater fish, spe cifically perch (Perca fluviatilis) and roach (Rutilus rutilus). -

Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in USDA National Wildlife Research Center the Midwest Symposia December 1997 Review of the Population Status and Management of Double- Crested Cormorants in Ontario C. Korfanty W.G. Miyasaki J.L. Harcus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants Part of the Ornithology Commons Korfanty, C. ; Miyasaki, W.G.; and Harcus, J.L., "Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997). Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center Symposia at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Symposium on Double- Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants 130 Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario By C. Korfanty, W. G. Miyasaki, and J. L. Harcus Abstract: We prepared this review of the status and pairs on the Canadian Great Lakes in 1997, with increasing management of double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax numbers found on inland water bodies. Double-crested auritus) in Ontario, with management options, in response to cormorants are protected in Ontario, and there are no concerns expressed about possible negative impacts of large population control programs. -

Double-Crested Cormorant Conflict Management and Research on Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report

Double-crested Cormorant Conflict Management And Research On Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report Prepared by Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Division of Resources Management Minnesota Department of Natural Resources US Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services Photo by Steve Mortensen This report summarizes cormorant conflict management and research that occurred on Leech Lake during 2005. The overall goal of this project is to determine at what level cormorant numbers can be managed for on the lake without having a significant negative effect on gamefish and on other species of colonial waterbirds that nest alongside cormorants on Little Pelican Island. Work conducted this summer went much better than anticipated and we are well on the way towards resolving cormorant conflict issues on Leech Lake. Cormorant Management Environmental Assessment An environmental assessment (EA) was prepared that gathered and evaluated information on cormorants and their effects on fish and other resources. We compiled, considered, and incorporated input from all parties that have an interest or concern about the proposed controlling of cormorants on Leech Lake. This document could have been written specifically so the Leech Lake Band could address the Leech Lake cormorant colony, but it was decided to prepare it as a joint effort between LLBO Division of Resources Management (DRM) and USDA Wildlife Services (WS), MN Department of Natural Resources (MN DNR), and US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). WS served as lead agency in this effort. By preparing it in this manner, it could be utilized by other agencies elsewhere in Minnesota if resource damage was documented. The EA proposed to reduce the Leech Lake colony more than 10% so, under provisions of the Federal Depredation Order, the Leech Lake Band submitted a request to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to go to a higher population reduction limit (reduction to 500 nests). -

PIELC-2016-Broshure-For-Sure.Pdf

WelcOME! Welcome to the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference (PIELC), the premier annual gathering for environmen- talists in the world! Now in its 34th year, PIELC unites thousands of activists, attorneys, students, scientists, and commu- nity members from over 50 countries to share their ideas, experience, and expertise. With keynote addresses, workshops, films, celebrations, and over 130 panels, PIELC is world-renowned for its energy, innovation, and inspiration. In 2011, PIELC received the Program of the Year Award from the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources, and in 2013 PIELC received the American Bar Assoication Law Student Division’s Public Interest Award. PIELC 2016, A LEGacY WORTH LeaVING “A Legacy Worth Leaving” is a response to the drastic need of daily, direct action of individuals in their communities. Cohesive leadership models must acknowledge that individual participation directs society’s impact on interdependent community and global systems. Diversity of cultures, talents, and specialties must converge to guide community initiatives in a balanced system. Each has a unique role that can no longer be hindered by the complacent passive-participation models of traditional leadership schemes. Building community means being community. This year at PIELC, we will be exploring alternative methods of approaching current ecological, social, and cultural paradigms. First, by examining the past – let us not relive our mistakes. Then, by focusing on the present. Days to months, months to years, years to a lifetime; small acts compound to the life-story of a person, a place, a planet. What legacy are you leaving? WIFI GUEST ACCOUNT LOGIN INSTRUCTIONS 1) Connect to the “UOguest” wireless network (do NOT connect to the “UOwireless” network). -

2015-Irs-Form-990.Pdf

Form 990 (2015) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . ✔ 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES’ (THE HSUS) MISSION IS TO CELEBRATE ANIMALS AND CONFRONT CRUELTY. MORE INFORMATION ON THE HSUS’S PROGRAM SERVICE ACCOMPLISHMENTS IS AVAILABLE AT HUMANESOCIETY.ORG. (SEE STATEMENT) 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 49,935,884 including grants of $ 5,456,871 ) (Revenue $ 440,435 ) EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT THE WORK OF EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT, WITH THE RELATED ACTIVITY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND COMMUNICATION TO A RANGE OF AUDIENCES, IS CONDUCTED THROUGH MANY SECTIONS INCLUDING DONOR CARE, COMPANION ANIMALS, WILDLIFE, FARM ANIMALS, COMMUNICATIONS, MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, CONFERENCES AND EVENTS, PUBLICATIONS AND CONTENT, THE HUMANE SOCIETY INSTITUTE FOR SCIENCE AND POLICY, FAITH OUTREACH, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND OUTREACH, HUMANE SOCIETY ACADEMY, CELEBRITY OUTREACH, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS. -

Reducing Bird Damage in the State of Vermont

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REDUCING BIRD DAMAGE IN THE STATE OF VERMONT In cooperation with: United States Department of Interior United States Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Program Region 5 The Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department Prepared by: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ANIMAL AND PLANT HEALTH INSPECTION SERVICE WILDLIFE SERVICES November 2015 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 NEED FOR ACTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 DECISIONS TO BE MADE ......................................................................................................... 21 1.5 SCOPE OF THIS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ............................................................. 21 1.6 RELATIONSHIP OF THIS DOCUMENT TO OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL DOCUMENTS . 24 1.7 AUTHORITY OF FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCIES ........................................................... 25 1.8 COMPLIANCE WITH LAWS AND STATUTES ....................................................................... 28 CHAPTER 2: -

Environmental Assessment

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT SCIENTIFIC COLLECTION PERMIT FOR DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANT STUDIES ON LEECH LAKE, MINNESOTA Prepared By: United States Department of Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Final April 2019 CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION 1.0 INTRODUCTION Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (hereafter, USFWS) has prepared this Environmental Assessment (EA) to consider the potential impacts to the human environment that may result from the take of Double-crested Cormorants, Phalacrocorax auritus, (hereafter, “cormorants”) at Leech Lake, Minnesota. The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe (hereafter, Band) is proposing an increase in the number of cormorants they are collecting in 2019 as part of two ongoing scientific research projects evaluating 1) cormorant diet and 2) long-term fish-cormorant population dynamics in the lake. We considered two alternatives for issuing scientific collection permits (SCP) in accordance with 50 C.F.R. § 21.23 of the governing regulations under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, as amended (MBTA) (16 USC 703– 712). This EA assists our compliance with the NEPA and helps us make an informed management decision. It also aids us in making a determination as to whether the actions could “significantly” impact the human environment, which includes, “the natural and physical environment and the relationship of people with that environment” (40 C.F.R. § 1508.14). “Significantly” under NEPA is defined by regulation 40 C.F.R. § 1508.27, and requires short-term and long-term consideration of both the context of a proposal and its intensity, and whether the impacts are beneficial or adverse. -

Workshop on Fire, People and the Central Hardwoods Landscape

United States Department of Proceedings: Workshop on Agriculture Forest Service Fire, People, and the Central Northeastern Hardwoods Landscape Research Station General Technical Report NE-274 March 12-14, 2000 Richmond, Kentucky All articles were received in digital format and were edited for type and style; each author is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of contributors from outside the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Computer programs described in this publication are available on request with the understanding that the U.S. Department of Agriculture cannot assure its accuracy, completeness, reliability, or suitability for any other purpose than that reported. The recipient may not assert any proprietary rights thereto nor represent it to anyone as other than a Government-produced computer program. Published by: For additional copies: USDA FOREST SERVICE USDA Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073-3294 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 September 2000 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.fs.fed.us/ne Proceedings: Workshop on Fire, People, and the Central -

Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics

\a Managing Protected . Areas in the Tropics i National Parks, Conservation, and Development The Role of Protected Areas in Sustaining Society Edited by JEFFREYA. MCNEELEYand KENTONR. MILLER Marine and Coastal Protected Areas A Guide for Planners and Managers By RODNEYV. SALM Assisted by JOHN R. CLARK Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics Compiled by JOHNand KATHYMACKINNON, Environmental Conservationists, based in UK; GRAHAMCHILD, former Director of National Parks and Wildlife Management, Zimbabwe; and JIM THORSELL,Executive Officer, Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas, IUCN, Switzerland Based on the Workshops on Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics World Congress on National Parks, Bali, Indonesia, October I982 Organised by the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas INTERNATIONALUNION FORCONSERVA~ON OF NATUREAND NATURALRESOURCES and the UNITEDNATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME INTERNATIONALUNION FORCONSERVATION OF NATUREAND NATURALRESOURCES, GLAND, SWKZERLAND 1986 - J IUCN - THE WORLD CONSERVATION UNION Founded in 1948, IUCN - the World Conservation Union - is a membership organisation comprising governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), research institutions, and conservation agencies in 120 countries. The Union’s objective is to promote and encourage the protection and sustainable utilisation of living resources. Several thousand scientists and experts from all continents form part of a network supporting the work of its six Commissions: threatened species, protected areas, ecology, sustainable development, environmental law, and environmental education and training. Its thematic programmes include tropical forests, wetlands, marine ecosystems, plants, the Sahel, Antarctica, population and sustainable development, and women in conservation. These activities enable IUCN and its members to develop sound policies and programmes for the conservation of biological diversity and sustainable development of natural resources. -

Building on Nature: Area-Based Conservation As a Key Tool for Delivering Sdgs

Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs CITATION For the publication: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. For individual case studies: Case study authors. 2021. Case study name. In: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Nigel Dudley ([email protected]) and Marianne Kettunen ([email protected]) PARTNERS Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) The Nature Conservancy (TNC) The World Bank Group UN Development Programme (UNDP) Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) WWF DISCLAIMER The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official opinions of the institutions involved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report and the work underpinning it has benefitted from the support of the following people: Sophia Burke (AmbioTEK CIC), Andrea Egan (UNDP), Marie Fischborn (PANORAMA), Barney Long (Re-Wild), Melanie McField (Healthy Reefs), Mark Mulligan (King’s College, London), Caroline Snow (proofreading), Sue Stolton (Equilibrium Research), Lauren Wenzel (NOAA), and from the many case study authors named individually throughout the publication. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement Double-Crested Cormorant Management in the United States

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Final Environmental Impact Statement Double-crested Cormorant Management in the United States U.S. Department of Interior Fish and Wildlife Service “Working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people” in cooperation with U.S. Department of Agriculture APHIS Wildlife Services “Providing leadership in wildlife damage management in the protection of America’s agricultural, industrial and natural resources, and safeguarding public health and safety” 2003 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT: Double-crested Cormorant Management RESPONSIBLE AGENCY: Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service COOPERATING AGENCY: Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services RESPONSIBLE OFFICIAL: Steve Williams, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Main Interior Building 1849 C Street Washington, D.C. 20240 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Shauna Hanisch, EIS Project Manager Division of Migratory Bird Management U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive MS-MBSP-4107 Arlington, Virginia 22203 (703) 358-1714 Brian Millsap, Chief Division of Migratory Bird Management U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive MS-MBSP-4107 Arlington, Virginia 22203 (703) 358-1714 i SUMMARY Populations of Double-crested Cormorants have been increasing rapidly in many parts of the U.S. since the mid-1970s. This abundance has led to increased conflicts, both real and perceived, with various biological and socioeconomic resources, including recreational fisheries, other birds, vegetation, and hatchery and commercial aquaculture production. This document describes and evaluates six alternatives (including the proposed action) for the purposes of reducing conflicts associated with cormorants, enhancing the flexibility of natural resource agencies to deal with cormorant conflicts, and ensuring the long-term conservation of cormorant populations. -

The Great Chain of Life: Wildlife and Marine Mammals

115_144 Ch 5 1/11/06 3:02 PM Page 115 CHAPTER 5 The Great Chain of Life: Wildlife and Marine Mammals hen The HSUS formed, it had a philosophical commitment to wildlife and marine mammal protection, but it lacked the resources to pursue those issues with vigor. The main focus of The HSUS dur- ing its first decade was on animals used for food and in research. Still, it made some tentative steps toward incorporating wildlife and marine mammals into its range of concerns. Opposition to hunting, mismanagement of ani- Wmal populations by state wildlife agencies, lethal predator control in the interests of agricul- ture, the clubbing of seals, and the harpooning of whales all emerged as target issues once the organization acquired the resources to address them. By 1970, the year John Hoyt joined The HSUS, the era’s burgeoning environmental con- sciousness had brought the plight of some animals, including whales, seals, dolphins, bears, wolves, and numerous endangered species, to greater public attention. One of the first things Hoyt did after coming to The HSUS was to create a wildlife issues program. During the 1970s Hoyt hired a number of specialists to work on wildlife and marine mammal issues. Guy Hodge, Hal Perry, Sue Pressman, Michael Fox, Patricia Forkan, and Natasha Atkins all helped to advance the program in those years. They witnessed some stunning victories in the realm of wildlife protection: the ban on DDT in 1971; enactment of the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the ban on predator poisons in 1972; and the signing of the CITES treaty and the pas- sage of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1973.