Niche Overlap Among Anglers, Fishers and Cormorants and Their Removals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verordnung Über Das Befahren Der Bundeswasserstraßen in Nationalparken Und Naturschutzgebieten Im Bereich Der Küste Von Meckl

Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Verordnung über das Befahren der Bundeswasserstraßen in Nationalparken und Naturschutzgebieten im Bereich der Küste von Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Befahrensregelungsverordnung Küstenbereich Mecklenburg-Vorpommern - NPBefVMVK) NPBefVMVK Ausfertigungsdatum: 24.06.1997 Vollzitat: "Befahrensregelungsverordnung Küstenbereich Mecklenburg-Vorpommern vom 24. Juni 1997 (BGBl. I S. 1542), die durch Artikel 30 der Verordnung vom 2. Juni 2016 (BGBl. I S. 1257) geändert worden ist" Stand: Geändert durch Art. 30 V v. 2.6.2016 I 1257 Fußnote (+++ Textnachweis ab: 10.7.1997 +++) Eingangsformel Auf Grund des § 5 Satz 3 des Bundeswasserstraßengesetzes in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 23. August 1990 (BGBl. I S. 1818) verordnet das Bundesministerium für Verkehr im Einvernehmen mit dem Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit: § 1 (1) Zum Schutz der Tier- und Pflanzenwelt wird das Befahren der Bundeswasserstraßen mit Wasserfahrzeugen, Sportfahrzeugen oder Wassersportgeräten und der Betrieb von ferngesteuerten Schiffsmodellen in dem 1. Nationalpark "Vorpommersche Boddenlandschaft" gemäß der Verordnung über die Festsetzung des Nationalparks Vorpommersche Boddenlandschaft vom 12. September 1990 (GBl. Sonderdruck Nr. 1466), die nach Artikel 3 Kapitel XII Nr. 30 Buchstabe a der Vereinbarung zum Einigungsvertrag vom 18. September 1990 in Verbindung mit Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 23. September 1990 (BGBl. 1990 II S. 885, 1239) mit den dort genannten Maßgaben fortgilt, 2. Nationalpark "Jasmund" gemäß der Verordnung über die Festsetzung des Nationalparks Jasmund vom 12. September 1990 (GBl. Sonderdruck Nr. 1467), die nach Artikel 3 Kapitel XII Nr. 30 Buchstabe b der Vereinbarung zum Einigungsvertrag vom 18. September 1990 in Verbindung mit Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 23. -

Bestandsaufnahme U. Bewertung Von Habitaten 2017 ... Boddengewässer

Verbundprojekt Schatz an der Küste Bestandsaufnahme und Bewertung von Habitaten und Wassernutzun- gen sowie räumliche Zonierungsempfehlungen zur Entwicklung einer Befahrensempfehlung für die Boddengewässer im Hotspot 29 Gefördert durch das Bundesamt für Naturschutz mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit. Diese Potenzialanalyse gibt die Auffassung und Meinung des Zuwendungsempfängers des Bundesprogramms wieder und muss nicht mit der Auffassung des Zuwendungsgebers übereinstimmen. Weitere Förderer: WWF Deutschland Projektbüro Ostsee Regionalplanung Verbundprojekt Schatz an der Küste Umweltplanung Bestandsaufnahme und Bewertung von Habitaten und Wassernutzungen sowie räumliche Zonierungs- Landschaftsarchitektur empfehlungen zur Entwicklung einer Befahrensempfehlung für die Boddengewässer im Hotspot 29 Landschaftsökologie Wasserbau Immissionsschutz Hydrogeologie Projekt-Nr.: 25427-00 Fertigstellung: November 2017 UmweltPlan GmbH Stralsund [email protected] www.umweltplan.de Hauptsitz Stralsund Postanschrift: Tribseer Damm 2 Geschäftsführerin: Dipl.-Geogr. Synke Ahlmeyer 18437 Stralsund Tel. +49 3831 6108-0 Fax +49 3831 6108-49 Niederlassung Rostock Majakowskistraße 58 18059 Rostock Tel. +49 381 877161-50 Außenstelle Greifswald Projektleiter: Dipl.-Landschaftsökol. Bahnhofstraße 43 Kristina Vogelsang 17489 Greifswald Tel. +49 3834 23111-91 Geschäftsführerin Mitarbeit: Dipl.-Biol. Dr. Jan Prinz Dipl.-Geogr. Synke Ahlmeyer Dipl.-Geogr. Ulrike Kerstan Zertifikate Dipl.-Kartogr. Ulrike Assmann Qualitätsmanagement -

Gewässergütebericht 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 Gewässergütebericht 2003 / 2004 2005 2006 Gewässergütebericht

Gewässergütebericht 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 Gewässergütebericht 2003 / 2004 2005 2006 Gewässergütebericht Ergebnisse der Güteüberwachung der Fließ-, Stand- und Küstengewässer und des Grundwassers in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Mecklenburg Vorpommern Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Landesamt für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Geologie Impressum Herausgeber: Landesamt für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Geologie Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Goldberger Straße 12, 18273 Güstrow Telefon 03843 - 777-0, Fax 03843 - 777-106 http://www.lung.mv-regierung.de, email: [email protected] Erarbeitet von: Bachor, Dr. Alexander; Federführung Kapitel 3 und 5 sowie Redaktion Carstens, Dr. Marina; Federführung Kapitel 3 Klitzsch, Stefan; Federführung Kapitel 2 Korczynski, Ilona Lemke, Gabriele; Federführung Kapitel 6 Mathes, Dr. Jürgen; Federführung Kapitel 4 Müller, Jörg Schenk, Marianne Seefeldt, Olaf; Federführung Kapitel 1 Schöppe, Christine Schumann, André Tonn, Bärbel Weber, Mario von; Federführung Kapitel 5 Der Gewässergütebericht 2003/2004/2005/2006 ist ein Gemeinschaftsprodukt der Abteilung Wasser und Boden des Landesamtes für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Geologie und des Seenreferates des Ministeriums für Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Gewässerkund- lichen Landesdienst der Staatlichen Ämter für Umwelt und Natur. Zu zitieren als: Gewässergütebericht Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2003/2004/2005/2006: Ergebnisse der Güteüberwachung der Fließ-, Stand- und Küstengewässer und des Grundwassers in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Herausgeber: Landesamt -

Kartenblattuebersicht TK10H.Pdf

Landesamt für innere Verwaltung Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Anlage zum Produktkatalog N-32 12° N-33 13° 14° Amt für Geoinformation, Vermessungs- und Katasterwesen Geobasisdaten amtlich flächendeckend aktuell Lübecker Straße 289, 19059 Schwerin 39 Telefon: 0385 588-56266,- 56268, Telefax: 0385 4773004-07 Ausgabe 2011 E-Mail: [email protected] 39-D-c-3 39-D-c-4 39-D-d-3 Übersicht der Topographischen Karte 1:10 000 Bakenberg Schwarbe Putgarten 51-A-b-2 51-B-a-1 51-B-a-2 51-B-b-1 Dranske Gramtitz Altenkirchen Vitt 51-A-a-4 51-A-b-3 51-A-b-4 51-B-a-3 51-B-a-4 51-B-b-3 52-A-a-4 52-A-b-3 Nomenklaturangabe für die Staatsgrenze Kloster Grieben Bug Wiek Breege Juliusruh Lohme Hankenufer Topographische Karte 1:10 000 Kartenblatt lieferbar 51-A-c-2 51-A-d-1 51-A-d-2 51-B-c-1 51-B-c-2 51-B-d-1 51-B-d-2 52-A-c-1 52-A-c-2 52-A-d-1 Insel Wittower Sassnitz- Landesgrenze Hiddensee Vitter BoddenFähre Fährhof Neuenkirchen Schaabe Glowe Bobbin Nipmerow Stubbenkammer 12 1 2 51-A-c-4 51-A-d-3 51-A-d-4 51-B-c-3 51-B-c-4 51-B-d-3 52-A-c-3 52-A-c-4 52-A-d-3 Sassnitz a b Kreisgrenze, Neuendorf Schaprode Granskevitz Trent Tribbevitz Rappin Sagard W Sassnitz Bearbeitungsgrenze der Grenze einer kreisfreien Stadt 3 4 34 49 50 51 52 Topographischen Karte 1:10 000 49-D-b-2 50-C-a-1 51-C-a-1 51-C-a-2 51-C-b-1 51-C-b-2 51-D-a-1 51-D-a-2 51-D-b-1 51-D-b-2 52-C-a-1 52-C-a-2 Teerbrenner- Bock, A des Amtes für Geoinformation see Darßer Ort Nordspitze Gellen Waase Freesen Kluis Gagern Patzig Ralswiek Lietzow Mukran Vermessungs- und Katasterwesen 1 2 1 2 49-D-b-4 50-C-a-3 -

Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in USDA National Wildlife Research Center the Midwest Symposia December 1997 Review of the Population Status and Management of Double- Crested Cormorants in Ontario C. Korfanty W.G. Miyasaki J.L. Harcus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants Part of the Ornithology Commons Korfanty, C. ; Miyasaki, W.G.; and Harcus, J.L., "Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997). Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center Symposia at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Symposium on Double- Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants 130 Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario By C. Korfanty, W. G. Miyasaki, and J. L. Harcus Abstract: We prepared this review of the status and pairs on the Canadian Great Lakes in 1997, with increasing management of double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax numbers found on inland water bodies. Double-crested auritus) in Ontario, with management options, in response to cormorants are protected in Ontario, and there are no concerns expressed about possible negative impacts of large population control programs. -

8. Ergänzung Des Flächennutzungsplans Der Gemeinde Wiek / Rügen

uhlig raith hertelt fuß | Partnerschaft für Stadt-, Landschafts- und Regionalplanung Freie Stadtplaner, Architekten, Landschaftsarchitektin Dipl. Ing. Kirsten Fuß Freie Landschaftsarchitektin Dipl. Ing. Lars Hertelt Freier Architekt Dr. Ing. Frank-Bertolt Raith Freier Stadtplaner und Architekt Prof. Dr. Ing. Günther Uhlig Freier Architekt und Stadtplaner Partnerschaftsgesellschaft Mannheim PR 100023 76133 Karlsruhe, Hirschstraße 53 Tel/Fax: 0721 378564 Tel: 0172 9683511 18439 Stralsund, Neuer Markt 5 Tel: 03831 203496 Fax: 03831 203498 www.stadt-landschaft-region.de [email protected] 8. Ergänzung des Flächennutzungsplans der Gemeinde Wiek / Rügen (Bereich Hafen Wiek) Genehmigungsexemplar 8. Ergänzung des Flächennutzungsplans Gemeinde Wiek / Rügen Begründung Inhaltsverzeichnis 1.) Ziele und Grundlagen der Planung 3 1.1.) Lage des Plangebietes / Notwendigkeit der Planung 3 1.2.) Landschaftsplan 3 1.3.) Bestandsaufnahme 3 1.3.1.) Aktuelle Flächennutzungen im bzw. angrenzend an das Plangebiet 3 1.3.2.) Schutzobjekte im bzw. angrenzend an das Plangebiet 3 1.3.3.) Laichschongebiet gemäß KüFVO M-V 4 1.3.4.) Bundeswasserstraße 4 1.3.5.) Sicherung gegenüber Naturgewalten 5 1.3.6.) Bodenverunreinigungen 5 2.) Städtebauliche Planung 5 2.1.) Nutzungskonzept 5 2.2.) Flächenbilanz 6 2.3.) Erschließung 6 2.3.1.) Verkehrliche Erschließung 6 2.3.2.) Ver- und Entsorgung 6 3.) Auswirkungen der Planung / Umweltbericht 6 3.1.) Abwägungsrelevante Belange 6 3.2.) Umweltbericht 7 3.2.1.) Allgemeines 7 3.2.2.) Gebiete von gemeinschaftlicher Bedeutung 7 3.2.3.) Naturhaushalt und Landschaftsbild 8 3.2.4.) Mensch und seine Gesundheit 11 3.2.5.) Kulturgüter und sonstige Sachgüter 11 3.2.6.) Wechselwirkungen zwischen umweltrelevanten Belangen 11 3.2.7.) Zusammenfassung 11 3.2.8.) Monitoring 12 8. -

Double-Crested Cormorant Conflict Management and Research on Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report

Double-crested Cormorant Conflict Management And Research On Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report Prepared by Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Division of Resources Management Minnesota Department of Natural Resources US Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services Photo by Steve Mortensen This report summarizes cormorant conflict management and research that occurred on Leech Lake during 2005. The overall goal of this project is to determine at what level cormorant numbers can be managed for on the lake without having a significant negative effect on gamefish and on other species of colonial waterbirds that nest alongside cormorants on Little Pelican Island. Work conducted this summer went much better than anticipated and we are well on the way towards resolving cormorant conflict issues on Leech Lake. Cormorant Management Environmental Assessment An environmental assessment (EA) was prepared that gathered and evaluated information on cormorants and their effects on fish and other resources. We compiled, considered, and incorporated input from all parties that have an interest or concern about the proposed controlling of cormorants on Leech Lake. This document could have been written specifically so the Leech Lake Band could address the Leech Lake cormorant colony, but it was decided to prepare it as a joint effort between LLBO Division of Resources Management (DRM) and USDA Wildlife Services (WS), MN Department of Natural Resources (MN DNR), and US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). WS served as lead agency in this effort. By preparing it in this manner, it could be utilized by other agencies elsewhere in Minnesota if resource damage was documented. The EA proposed to reduce the Leech Lake colony more than 10% so, under provisions of the Federal Depredation Order, the Leech Lake Band submitted a request to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to go to a higher population reduction limit (reduction to 500 nests). -

PIELC-2016-Broshure-For-Sure.Pdf

WelcOME! Welcome to the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference (PIELC), the premier annual gathering for environmen- talists in the world! Now in its 34th year, PIELC unites thousands of activists, attorneys, students, scientists, and commu- nity members from over 50 countries to share their ideas, experience, and expertise. With keynote addresses, workshops, films, celebrations, and over 130 panels, PIELC is world-renowned for its energy, innovation, and inspiration. In 2011, PIELC received the Program of the Year Award from the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources, and in 2013 PIELC received the American Bar Assoication Law Student Division’s Public Interest Award. PIELC 2016, A LEGacY WORTH LeaVING “A Legacy Worth Leaving” is a response to the drastic need of daily, direct action of individuals in their communities. Cohesive leadership models must acknowledge that individual participation directs society’s impact on interdependent community and global systems. Diversity of cultures, talents, and specialties must converge to guide community initiatives in a balanced system. Each has a unique role that can no longer be hindered by the complacent passive-participation models of traditional leadership schemes. Building community means being community. This year at PIELC, we will be exploring alternative methods of approaching current ecological, social, and cultural paradigms. First, by examining the past – let us not relive our mistakes. Then, by focusing on the present. Days to months, months to years, years to a lifetime; small acts compound to the life-story of a person, a place, a planet. What legacy are you leaving? WIFI GUEST ACCOUNT LOGIN INSTRUCTIONS 1) Connect to the “UOguest” wireless network (do NOT connect to the “UOwireless” network). -

Bug Peninsula/NW-Rügen

Quaternary Science Journal GEOZOn SCiEnCE MEDiA Volume 58 / number 2 / 2009 / 164–173 / DOi 10.3285/eg.58.2.05 iSSn 0424-7116 E&G www.quaternary-science.net Coastal evolution of a Holocene barrier spit (bug peninsula/NW- Rügen) deduced from geological structure and relative sea-level Michael naumann , Reinhard lampe, Gösta Hoffmann Abstract: The Bug peninsula/NW Rügen located at the south-western Baltic coast has been investigated to study coastal barrier evolution depending on Holocene sea-level rise. In this so far minor explored coastal section 25 sediment cores, seven ground-penetrating radar tracks and six sediment-echosounder tracks were collected from which six depositional facies types were derived. The data show that the recent peninsula consists of an about 10 m thick Holocene sediment sequence, underlain by Pleistocene till or (glaci-) fluviolimnic fine sand. Although no absolute age data could be gathered to estimate the chronostratigraphy of the sedimentary sequence the relation of the depositional facies to the local relative sea-level curve allow the reconstruction of the palaeogeographic evolution of the Bug barrier spit. The marine inundation of the area occurred around 7,000 BC during the Littorina transgression. In this stage the sea level rose rapidly and generated a fast increasing subaquatic accommodation space, where fine clastic material was deposited nearly or below the wave base and levelled the former relief. Accumulative coastal landforms grew to only minor extent because the accom- modation space increased faster than it was filled with material from neighbouring eroding cliffs. Since the time the sea-level rise decreased accumulation became more dominant and the main barrier was built up in only some two thousand years. -

Ein Vergleich Zwischen Küstenlagunen Der Südlichen Ostsee

Stoffflüsse in Makrophytensystemen: Ein Vergleich zwischen Küstenlagunen der südlichen Ostsee Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald vorgelegt von Jutta Meyer geboren am 03.05.1982 in Berlin Rostock, 8. Februar 2017 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Werner Weitschies 1. Gutachter: PD. Dr. habil. Irmgard Blindow 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. habil. Brigitte Nixdorf Tag der Promotion: 16.06.2017 Abstract In the past decades, Eutrophication led to an unsatisfying ecological state of several coastal lagoons around the Baltic Sea, resulting e. g. in extensive harmfull algae blooms. To regain a good ecological state of coastal waters was therefore a central aim of the EU-Water Framework Directive. For restoration of freshwater ecosystem submerged macrophytes, such as charophytes and angiosperms, are already used to improve water quality (Gulati et al., 2008; Hilt et al., 2006). Macrophytes directly reduce water turbidity as they promote sedimentation of suspended matter and limit resuspension of sediment. They also provide zooplankton a refuge against predators. As zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, macro- phytes indirectly promote reduction of phytoplankton biomass and therefore, reduce water turbidity. Additionally, they can successfully compete with phytoplankton for nutrients. It was stated by Jeppesen et al., (1994) that these feedback mechanisms are less effective in brackish waters, as e. g. zooplankton grazing on phytoplankton is less efficient due to a different species composition and a higher mortality of zooplankton caused by fishes and invertebrates within macrophyte stands. In the present thesis, interactions between submerged macrophytes and their biotic and abiotic environment were determined in two shallow brackish coastal lagoons of the southern Baltic Sea. -

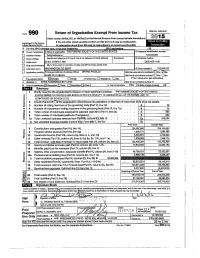

2015-Irs-Form-990.Pdf

Form 990 (2015) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . ✔ 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES’ (THE HSUS) MISSION IS TO CELEBRATE ANIMALS AND CONFRONT CRUELTY. MORE INFORMATION ON THE HSUS’S PROGRAM SERVICE ACCOMPLISHMENTS IS AVAILABLE AT HUMANESOCIETY.ORG. (SEE STATEMENT) 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 49,935,884 including grants of $ 5,456,871 ) (Revenue $ 440,435 ) EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT THE WORK OF EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT, WITH THE RELATED ACTIVITY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND COMMUNICATION TO A RANGE OF AUDIENCES, IS CONDUCTED THROUGH MANY SECTIONS INCLUDING DONOR CARE, COMPANION ANIMALS, WILDLIFE, FARM ANIMALS, COMMUNICATIONS, MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, CONFERENCES AND EVENTS, PUBLICATIONS AND CONTENT, THE HUMANE SOCIETY INSTITUTE FOR SCIENCE AND POLICY, FAITH OUTREACH, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND OUTREACH, HUMANE SOCIETY ACADEMY, CELEBRITY OUTREACH, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS. -

Reducing Bird Damage in the State of Vermont

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REDUCING BIRD DAMAGE IN THE STATE OF VERMONT In cooperation with: United States Department of Interior United States Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Program Region 5 The Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department Prepared by: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ANIMAL AND PLANT HEALTH INSPECTION SERVICE WILDLIFE SERVICES November 2015 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 NEED FOR ACTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 DECISIONS TO BE MADE ......................................................................................................... 21 1.5 SCOPE OF THIS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ............................................................. 21 1.6 RELATIONSHIP OF THIS DOCUMENT TO OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL DOCUMENTS . 24 1.7 AUTHORITY OF FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCIES ........................................................... 25 1.8 COMPLIANCE WITH LAWS AND STATUTES ....................................................................... 28 CHAPTER 2: