Chad Econornic Situation and Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Development

Report No. 16567-CD Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Public Disclosure Authorized Development October 21, 1997 Human Development, Group IV Atrica Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AMTT Agricultural Marketing and Technology Transfer Project AV Association Villageoise BCA Bceufs de culture attelde BEAC Banque des Etats de l'Afrique Centrale BET Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti BIEP Bureau Interminist6rieI d'Etudes et des Projets BNF Bureau National de Frdt CAER Compte Autonome d'Entretien Routier CAR Central African Republic CFA Communautd Financiere Africaine CILSS Comite Inter-etats de Lutte Contre la Sdcheresse au Sahel DCPA Direction de la Commercialisation des Produits Agricoles DD Droit de Douane DPPASA Direction de la Promotion des Produits Agricoles et de la Sdcur DSA Direction de la Statistique Agricole EU European Union FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FEWS Famine Early Warning System FIR Fonds d'Investissement Rural GDP Gross Domestic Product GNP Gross National Product INSAH Institut du Sahel IRCT Institut de Recherche sur le Coton et le Textile LVO Lettre de Voiture Obligatoire MTPT Ministare des Travaux Publics et des Transports NGO Nongovernmental Organization ONDR Office National de Developpement Rural PASET Projet d'Ajustement Sectoriel des Transports PRISAS Programme Regional de Renforcement Institationnel en matie sur la Sdcuritd Alimentaire au Sahel PST Projet Sectoriel Transport RCA Republique Centrafrcaine -

Rabies Control in N'djamena, Chad

Rabies control in N’Djamena, Chad INAUGURALDISSERTATION zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Monique Sarah Léchenne Aus Sceut/Glovelier JU, Schweiz Basel, 2017 Original document stored on the publication server of the University of Basel edoc.unibas.ch This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Genehmigt von der Philosphisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Jakob Zinsstag und Prof. Dr. Louis Nel Basel, den 10. November 2015 Prof. Dr. J. Schibler Dekan der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät « Ce n’est pas une vie que de ne pas bouger !» Alexandre Yersin <What was life, if you don’t commit to something?> <Das ist doch kein Leben, wenn man nichts unternimmt> To the anonymous children with the puppy on my desktop picture - my daily motivation (Plate 1) Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Index of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Index of Figures ....................................................................................................................... v Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................ viii I. Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

Contrôle De La Peste Porcine Africaine (PPA) Dans Les Élevages Porcins Traditionnels Au Tchad

Journal of Animal &Plant Sciences, 2012. Vol.15, Issue 3: 2261-2266 Publication date 31/10/2012, http://www.m.elewa.org/JAPS ; ISSN 2071-7024 Contrôle de la Peste Porcine Africaine (PPA) dans les élevages porcins traditionnels au Tchad Ban-bo B.A*., Idriss O.A**. ; Squarzoni C.D*** * Faculté des Sciences exactes et appliqués - Université de N’Djaména ** Coordonnateur National des Projet et programme Grippe Aviaire ; *** Conseillère technique principale du projet grippe aviaire OSRO/CHD/602/EC *Auteur pour toute correspondance, Email: [email protected] Mots clés : peste porcine africaine, contrôle, porcs Tchad, abattage systématique. Keywords : African swine fever control, pigs, Chad, Culling. 1. RÉSUMÉ Le seul moyen de lutte contre la PPA semble être la prophylaxie sanitaire. Beaucoup des pays en Amérique du Sud comme en Europe sont parvenus à éradiquer cette maladie en procédant à l’abattage systématique des porcs dans les foyers (fermes, villages, district.) définis par les autorités administratives de la place. Cette prophylaxie sanitaire est souvent accompagnée d’une surveillance générale ou ciblée. Les approches et les méthodes d’abattage porcin ont été variées selon les moyens et la volonté dont disposent les services vétérinaires en charge de la question. L’expérience du Tchad est probante donnant lieu à des spéculations et favorisant la propagation de la maladie. Les textes administratifs (Loi, Arrêtés ministériels et Décisions) ont servi de bases de travail. Des mesures de police sanitaire ont été prises dès l’annonce officielle de la PPA à l’extrême Nord du Cameroun. Des missions de sensibilisations et de formations des producteurs ont été organisées. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD2408 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT PAPER ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED ADDITIONAL GRANT AND RESTRUCTURING IN THE AMOUNT OF (SDR 36.5) MILLION (US$50 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF CHAD FOR THE Public Disclosure Authorized EDUCATION SECTOR REFORM PROJECT PHASE 2 June 2, 2016 Education Global Practice Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the Public Disclosure Authorized performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective April 30, 2017) Currency Unit = SDR 0.72538389 SDR = US$1 US$1 = FCFA 602.20 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AF Additional Financing AFD French Development Agency / Agence Française de Développement AFDB African Development Bank APE Parents Association / Association des Parents d'Élèves APICED Agency for Promoting Community Initiatives in Education / Agence pour la Promotion des Initiatives Communautaires en Éducation CCT Contractualized Community Teacher CFC In-Service Training Center / Centre de Formation Continue CNC National Curriculum Center / Centre National des Curricula CPF Country Partnership Framework CT Community Teacher DA Designated Account DASNS School Feeding, Health, and Nutrition Directorate / Direction Alimentation, Santé, et Nutrition Scolaires DFE Teacher Training Department / -

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data Collected January – February 2016

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data collected January – February 2016 Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Stephanie Brunelin and Simon Renk. Primary data was collected in collaboration with ACF and other partners, under the overall supervision of Simon Renk. Acknowledgments go to Abdoulaye Ndiaye for the maps and to William Olander for cleaning the survey data. The mission wishes to acknowledge valuable contributions made by various colleagues in WFP country office Chad and WFP Regional Bureau Dakar. Special thanks to Cecile Barriere, Yannick Pouchalan, Maggie Holmesheoran, Patrick David, Barbara Frattaruolo, Ibrahim Laouali, Mohamed Sylla, Kewe Kane, Francis Njilie, Analee Pepper, Matthieu Tockert for their detailed and useful comments on earlier versions of the report. The report has also benefitted from the discussions with Marlies Lensink, Malick Ndiaye and Salifou Sanda Ousmane. Finally, sincere appreciation goes to the enumerators, traders and shop-owners for collecting and providing information during the survey. Acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FEWS NET Famine Early Warning System Network GDP Gross Domestic Product GPI Gender Parity Index IDP Internally Displaced People IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund IOM International Organization for Migration MT Metric Ton NAMIS Nigeria Agricultural Market Information Service OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

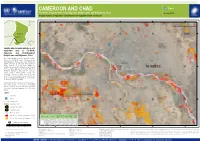

Cameroon and Chad

CAMEROON AND CHAD Flood Far-North, Cameroon and Chari-Baguirmi, Hadjer-Lamis and N'Djamena, Chad FL20200826TCD Imagery analysis: 9 September 2020 | Published 11 September 2020 | Version 1.0 14?57'0"E 15?0'0"E 15?3'0"E 15?6'0"E 15?9'0"E N N " " 0 0 ' ' 9 9 ? ? 2 2 C H A D 1 1 Ndjamena Map location Satellite detected water extents as of 9 September 2020 in Far-North, Cameroon and Chari-Baguirmi, Hadjer-Lamis and N'Djamena, Chad This map illustrates satellite-detected surface waters over Far-North region of Cameroon and Chari-Baguirmi, Hadjer-Lamis and N'Djamena regions of Chad as observed from Sentinel-1 N N " " 0 0 ' image acquired on 9 Sep 2020. Within the ' 6 6 ? ? 2 2 1 analyzed area of about 800 km2, a total of about 1 30 km2 of lands appear to be flooded. Based on Worldpop population data and the detected surface waters, about 28,000 people are potentially exposed or living close to flooded areas. This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Please send ground feedback to UNITAR - UNOSAT. Important Note: Flood analysis from radar images may underestimate the presence of standing waters in built-up areas and densely vegetated areas due to backscattering properties of the radar signal. Legend City/Town N N " " 0 0 ' ' 3 Airport 3 ? ? 2 2 1 1 Primary road Secondary road International boundary Region boundary Reference water Population Total District Total Population Flood Extent Potentially Satellite detected water [9 September 2020] Country Region District Area in AOI Population in Potentially (km2) Exposed -

French) (Arabic

Coor din ates: 1 5 °N 1 9 °E Chad Tashād; French: Tchad ﺗﺸﺎد :Chad (/tʃæd/ ( listen); Arabic Republic of Chad pronou nced [tʃad]), officially the Republic of Chad (Jumhūrīyat Tshād; French: République République du Tchad (French ﺟﻤﮭﻮرﯾﺔ ﺗﺸﺎد :Arabic) (Arabic) ﺟﻣﮫورﻳﺔ ﺗﺷﺎد du Tchad lit. "Republic of the Chad"), is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the Jumhūrīyat Tashād north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west. It is the fifth largest country in Africa and the second-largest in Central Africa in terms of area. Coat of arms Chad has several regions: a desert zone in the north, an arid Flag Sahelian belt in the centre and a more fertile Sudanian Motto: Savanna zone in the south. Lake Chad, after which the "Unité, Travail, Progrès" (French) country is named, is the largest wetland in Chad and the "Unity, Work, Progress" (Arabic) "اﻻﺗﺣﺎد، اﻟﻌﻣل، اﻟﺗﻘدم" second-largest in Africa. The capital N'Djamena is the largest city. Chad's official languages are Arabic and French. Anthem: Chad is home to over 200 different ethnic and linguistic La Tchadienne (French) groups. The most popular religion of Chad is Islam (at 55%), (Arabic) ﻧﺷﻳد ﺗﺷﺎد اﻟوطﻧﻲ followed by Christianity (at 40%). The Chadian Hymn Beginning in the 7 th millennium BC, human populations moved into the Chadian basin in great numbers. By the end of the 1st millennium AD, a series of states and empires had risen and fallen in Chad's Sahelian strip, each focused on controlling the trans-Saharan trade routes that passed through the region. -

2014-2016 Strategic Response Plan

2014-2016 STRATEGIC RESPONSE PLAN Republic of Chad January 2014 Prepared by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team PERIOD: SUMMARY January – December 2014 Strategic objectives 100% 1. Track and analyse risk and vulnerability, integrating findings into 12 million humanitarian and development programming. total population 2. Support vulnerable populations to better cope with shocks by responding earlier to warning signals, by reducing post-crisis recovery 24% of total population times and by building capacity of national actors. 2.87 million 3. Deliver coordinated and integrated life-saving assistance to people estimated number of people in affected by emergencies. need of humanitarian aid Priority actions 18% of total population The overarching aim of the Coordination cluster, in collaboration with all 2.1 million stakeholders, is to mobilize and coordinate appropriate principled and people targeted for humanitarian timely humanitarian assistance in response to assess needs. Priority aid in this plan activities for the cluster are to ensure robust and strategic coordination through the humanitarian architecture of the HCT, ICC and clusters and to Key categories of people in need: improve analysis and reporting on the humanitarian situation. Food insecure Furthermore, the Coordination cluster will facilitate contingency planning, 2.4 million inter-agency rapid needs assessments, needs analysis and response 135,533 Children <5 SAM while building the capacities of national authorities to respond to emergencies. 300,647 Children <5 MAM Malnourished Early recovery activities will be implemented in the Sahel-belt as well as 182,393 Pregnant and in West and South Chad benefiting 700,000 people. Planned activities Lactating Mothers include capacity building (disaster risk reduction, conflict management, etc.) of national authorities and communities to reduce vulnerabilities and 466,850 Refugees strengthening community resilience. -

Project/Programme Proposal to the Adaptation Fund

Amended in November 2013 PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL TO THE ADAPTATION FUND PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Project/Programme Category: Regular Country/ies: Chad Title of Project/Programme: STRENGTHENING THE RESILIENCE OF FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE COMMUNITIES TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAD (RECOPAT) Type of Implementing Entity: REGIONAL IMPLEMENTING ENTITY (RIE) Implementing Entity: Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS) Executing Entity/ies: Ministry of Environment and Fisheries/ General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture of Chad Amount of Financing Requested US$9,600,000 (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) I- Project / Programme Background and Context: General Introduction Chad is a Sahelian country extending over about 1800 km from North to South and 1000 km from East to West. This vast territory of 1 284 000 km is located between the 8th and 23rd northern parallels and the 14th and 24th eastern meridians., ², is. Chad is bordered by Sudan to the East, Cameroon, Nigeria and Niger to the West, Libya to the North, and the Central African Republic to the South. It has the shape of a semi-basin open towards the West and with turned up edges in the North. Chad’s population is estimated at 14 452 543 inhabitants (WB, 2016), with a sex ratio estimated at 0.93 (male(s)/female) in 2016 (CIA, The World Fact book). The population is predominantly rural with an estimated rate of 77,38% (WB, 2016). It is unevenly distributed due to contrasts in climate and physical geography; the highest density is found in the southwest, particularly around Lake Chad and points south. The anthropogenic pressure in this area is accentuated by the strong flow of refugees from Sudan and Central African Republic, which strains Chad’s limited resources and create tensions in host communities.