Considerations of Wildlife Resources and Land Use in Chad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kanem Rural Development Project (Proder-K) Project Completion Report Validation

IFAD - REPUBLIC OF CHAD KANEM RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (PRODER-K) PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT VALIDATION A. Basic Data A. Basic Project Approval (US$ Actual Data m) (US$ m) Region WCA Total project costs 14.3 Country Republic of IFAD Loan and % of 13.0 90.8% Chad total Loan Number 607-TD Borrower 1.0 7.1% Type of project Rural Co-financier 1 (sub-sector) development Financing Type Loan Co-financier 2 Lending Terms1 HI Co-financier 3 Date of Approval April 2003 Co-financier 4 Date of Loan 15 May 2003 From Beneficiaries 300,000 2.1% Signature Date of 15 May 2005 From Other Sources: Effectiveness Loan Amendments None Number of beneficiaries 90,000 – 8,560 (if appropriate, specify if 100,000 direct direct or indirect) beneficiaries Loan Closure Cooperating Institution UNOPS UNOPS Extensions Country L.L. Nsimpasi Loan Closing Date 31 December 30 June Programme U. Demirag 2013 2010 Managers M. Béavogui (ad interim) A. Lhommeau Regional M. Béavogui Mid-Term Review Mentioned in None Director(s) AR, without date PCR Reviewer Ernst IFAD Loan 26.2 Schaltegger Disbursement at project (consultant) completion (%) PCR Quality Felloni Control Panel Muthoo Please provide any comment if required Sources:Presidents Report 2003, PCR 2010 B. Project Outline 1. The project, laid out for a period of eight years, covered the region of Kanem, which comprised the departments of Kanem and Bahr-El-Ghzal, both located about 300 km North of Ndjamena. It built on experience gained through the a predecessor project, the Projet de 1 According to IFAD’s Lending Policies and Criteria, there are three types of lending terms: highly concessional (HI), intermediate (I) and ordinary (O). -

Some Hyphaene Species from the Botanic Gardens, Catrcutta

I9701 FURTADO: HYPHAENE SomeHyphaene Speciesfrom the Botanic Gardens,Catrcutta C. X. Funrllo Singapore From time to time Hyphaene theboica trations to show its habit, stated that "to is mentioned as a palm that has been H. thebaica was be seen in many a successfullygrown in India. The only gardenof India and Ceylon," (p. 165), Indian speciesthat was commonly mis- an opinion found reiteratedseveral times taken for H. thebaica was distinguished by other writers. by Beccari (1908) under the name of Nevertheless,I was unable to receive H. ind,ica Becc. Nevertheless,Blatter, a fruit from India or Ceylon of a genuine who in his monographicwork The Palms H. thebaica as typified by Martius ol British Ind,ia and Ceylon (1926) ad- (1838). However in the region of mitted 11. inilica as a good speciesand Thebes there seems to occur also a re-describedit with photographic illus- I. Hyphaene Bzssel growing at the Calcutta Ia. Hyphaene Bzssei. Portion of rachiila, part Botanic Garden under the name f1. thebaica. of petiole, hastula and base o{ leaf, {ruit in Photo by T. A. Davis. section. Photo bv Juraimi. PRINCIPES [Vol. 14 2. Hyphaene Bussei at Calcutta. Photo by T. A. Davis. species that is referable to the group "H. namedby Beccari (1924,p.32) as muhiformis" and Beccari's H. thebaica (1924, PL 20) seemsto be referablealso to the latter group, many forms of which are known from Kenya. Apparently, Blatter followed Beccari in identifying "H. H. thebaica with a form of multi- formis," and not with 1/. thebaica (L.) "the Martius; for while he noted that young plants are of slow and precarious growth" in India and Ceylon, older o'much plants were better developed" there than the trees in Egypt (p. -

Notes Courtes

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40114541 Birds of Waza new to Cameroon: corrigenda and addenda Article · January 2000 Source: OAI CITATIONS READS 3 36 2 authors: Paul Scholte Robert Dowsett Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit Private University Consortium Ltd 136 PUBLICATIONS 1,612 CITATIONS 62 PUBLICATIONS 771 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Works of dates of publication View project Dragon Tree Consortium View project All content following this page was uploaded by Paul Scholte on 05 June 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 2000 29 Short Notes — Notes Courtes Birds of Waza new to Cameroon: corrigenda and addenda In their annotated list of birds of the Waza area, northern Cameroon, Scholte et al. (1999) claimed 11 species for which there were no previous published records from Cameroon “mainly based on Louette (1981)”. In fact, their list included 14 such species, but there are previous published records for most, some missed by Louette (1981), some of which had been listed by Dowsett (1993). We here clarify these records and give additional notes on two other species of the area. Corrigenda Ciconia nigra Black Stork (Dowsett 1993, based on Robertson 1992). Waza. Not claimed as new by Scholte et al. (1999), but the previous record mentioned by them is unpublished (Vanpraet 1977). Platalea leucorodia European Spoonbill (new). Phoenicopterus ruber Greater Flamingo (new). Not claimed as new by Scholte et al. (1999), but the previous record mentioned by them is unidentifiable as to species (Louette 1981). -

FOOTPRINTS in the MUD of AGADEM Eastern Niger's Way

Tilman Musch: FOOTPRINTS IN THE MUD OF AGADEM … FOOTPRINTS IN THE MUD OF AGADEM Eastern Niger’s way towards the Anthropocene Tilman Musch Abstract: Petrified footprints of now extinct rhinos and those of humans in the mud of the former lake Agadem may symbolise the beginning of an epoch dominated by humans. How could such a “local” Anthropocene be defined? In eastern Niger, two aspects seem particularly important for answering this question. The first is the disappearance of the addax in the context of the megafauna extinction. The second is the question how the “natural” environment may be conceived by the local Teda where current Western discussions highlight the “hybridity” of space. Keywords: Anthropocene, Teda, Space, Conservation, addax Agadem is a small oasis in eastern Niger with hardly 200 inhabitants. Most of them are camel breeding nomadic Teda from the Guna clan. Some possess palm trees there. The oasis is situated inside a fossil lake and sometimes digging or even the wind uncovers carbonised fish skeletons, shells or other “things from another time” (yina ŋgoan), as locals call them. But when a traveler crosses the bed of the lake with locals, they make him discover more: Petrified tracks from cattle, from a rhinoceros1 and even from a human being who long ago walked in the lake’s mud.2 1 Locals presume the tracks to be those of a lion. Nevertheless, according to scholars, they are probably the tracks of a rhinoceros. Thanks for this information are due to Louis Liebenberg (Cybertracker) and Friedemann Schrenk (Palaeanthropology; Senckenberg Institute, Frankfurt am Main). -

History of Species Reviewed Under Resolution Conf

AC17 Inf. 3 (English only/ Solamente en inglés/ Seulement en anglais) HISTORY OF SPECIES REVIEWED UNDER RESOLUTION CONF. 8.9 (Rev.) PART 1: AVES Species Survival Network 2100 L Street NW Washington, DC 20037 July 2001 AC17 Inf. 3 – p. 1 SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW: PHASE 1 NR = none reported Agapornis canus: Madagascar Madagascar established an annual export quota of 3,500 in 1993, pending the results of a survey of the species in the wild (CITES Notification No. 744). Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Quota 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3200 Exports 4614 5495 5270 3500 6200 • Export quota exceeded in 1994, 1995, 1996 and 1998. From 1994 - 1998, export quota exceeded by a total of 7,579 specimens. • Field project completed in 2000: R. J. Dowsett. Le statut des Perroquets vasa et noir Coracopsis vasa et C. nigra et de l’Inséparable à tête grise Agapornis canus à Madagascar. IUCN. Agapornis fischeri: Tanzania Trade suspended in April 1993 (CITES Notification No. 737). Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Quota NR NR NR NR NR NR Exports 300 0 0 2 0 • Field project completed in 1995: Moyer, D. The Status of Fischer’s Lovebird Agapornis fischeri in the United Republic of Tanzania. IUCN. • Agapornis fischeri is classified a Lower Risk/Near Threatened by the IUCN. Amazona aestiva: Argentina 1992 status survey underway. Moratorium on exports 1996 preliminary survey results received quota of 600. Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Chick Quota 1036 2480 3150 Juvenile Quota 624 820 1050 Total Quota NR 600 NR 1000 Exports 19 24 130 188 765 AC17 Inf. -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

The First Complete Mitogenome of Red-Bellied Parrot (Poicephalus Rufiventris) Resolves Phylogenetic Status Within Psittacidae

Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resources ISSN: (Print) 2380-2359 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tmdn20 The first complete mitogenome of red-bellied parrot (Poicephalus rufiventris) resolves phylogenetic status within Psittacidae Subir Sarker, Shubhagata Das, Seyed A. Ghorashi, Jade K. Forwood, Karla Helbig & Shane R. Raidal To cite this article: Subir Sarker, Shubhagata Das, Seyed A. Ghorashi, Jade K. Forwood, Karla Helbig & Shane R. Raidal (2018) The first complete mitogenome of red-bellied parrot (Poicephalus rufiventris) resolves phylogenetic status within Psittacidae, Mitochondrial DNA Part B, 3:1, 195-197, DOI: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1437818 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2018.1437818 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 10 Feb 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 24 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tmdn20 MITOCHONDRIAL DNA PART B: RESOURCES, 2018 VOL. 3, NO. 3, 195–197 https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2018.1437818 MITOGENOME ANNOUNCEMENT The first complete mitogenome of red-bellied parrot (Poicephalus rufiventris) resolves phylogenetic status within Psittacidae Subir Sarkera , Shubhagata Dasb, Seyed A. Ghorashib, Jade K. Forwoodc, Karla Helbiga and Shane R. Raidalb aDepartment of Physiology, Anatomy and Microbiology, School of Life Sciences, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia; bSchool of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University, Albury, Australia; cSchool of Biomedical Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Albury, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper describes the genomic architecture of a complete mitogenome from a red-bellied parrot Received 18 January 2018 (Poicephalus rufiventris). -

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

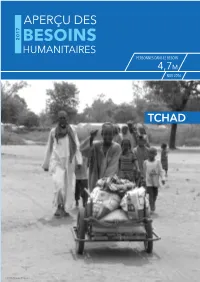

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

Antibacterial Activities of Hyphaene Thebaica (Doum Palm) Fruit Extracts Against Intestinal Microflora and Potential Constipatio

Tanzania Journal of Science 47(1): 104-111, 2021 ISSN 0856-1761, e-ISSN 2507-7961 © College of Natural and Applied Sciences, University of Dar es Salaam, 2021 Antibacterial Activities of Hyphaene thebaica (Doum Palm) Fruit Extracts against Intestinal Microflora and Potential Constipation Associated Pathogens in Yola Metropolis, Nigeria Joel Uyi Ewansiha 1*, Chidimma Elizabeth Ugo 1, Damaris Ibiwumi Kolawole 1, 2 and Lilian Sopuruchi Orji 3 1Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Technology, Yola, Nigeria. 2Department of Food Science and Technology, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. 3Bio-resources Development Centre, National Biotechnology Development Agency, Lugbe, Abuja Nigeria. Emails: [email protected]*; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] *Corresponding author Received 1 Nov 2020, Revised 25 Dec 2020, Accepted 28 Dec 2020, Published Feb 2021 Abstract This study aimed at determining the antibacterial activities of Hyphaene thebaica fruit extracts against some intestinal constipation associated bacteria. Qualitative analysis of some phytochemical constituents, agar well diffusion and broth dilution methods were used to determine the zones of inhibition and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the plant extracts. Phytochemical components viz flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids, tannins, phenols, alkaloids, glycosides and steroids were detected in the plant extracts, and the test organisms were susceptible to the plant extracts. The diameter zone of inhibition (DZI) obtained with n-hexane extract ranged from 15.10 ± 0.51 mm to 2.0 ± 0.55 mm against K. pneumoniae, 10.20 ± 0.57 mm to 2.00 ± 0.35 mm against P. aeruginosa and 8.00 ± 0.35 mm to 1.00 ± 0.55 mm against S. -

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

Tcd Map Borkoufr A1l 20210325.Pdf

TCHAD Province du Borkou Mars 2021 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 18°0'0"E 18°30'0"E 19°0'0"E 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E Goho Mademi Tomma Zizi Sano Diendaleme Madagala Mangara Dao Tiangala Louli Kossamanga Adi-Ougini Enneri Foditinga Massif de Nangara Dao Aorounga N I G E R Enneri Tougoui Yi- Gaalinga Baudrichi Agalea Madagada Enneri Maleouni Ehi Ooyi Tei Trama Aite Illoum Goa Yasko Daho-Mountou Kahor Doda Gerede Meskou Ounianga Tire Medimi Guerede Enneri Tougoul Ounianga-Kebir TIBESTI EST Moiri Achama Ehine Sata Tega Bezze Edring Tchige Kossamanga OmanKatam Garda-Goulji Ourede Ounianga-Kebir Fochimi Borkanga Nandara Enneri Tamou 19°0'0"N Sabka 19°0'0"N Chiede Ourti Tchigue Kossamanga Enneri Bomou Bellah Erde Bellah Koua Ehi Kourri Kidi Bania Motro Kouroud Bilinga Ehi Kouri Ounianga Serir Ouichi Kouroudi Ouassar Ehi Sao Doma Douhi Ihe Yaska Terbelli Tebendo Erkou T I B E S T I Soeka Latma Tougoumala Ehi Ouede-Ouede Saidanga Aragoua Nodi Tourkouyou Erichi Enneri Chica Chica Bibi Dobounga Ehi Guidaha Zohur Gouri Binem Arna Orori Ehi Gidaha Gouring TIBESTI OUEST Enneri Krema Enneri Erkoub Mayane An Kiehalla Sole Somma Maraho Rond-Point de Gaulle Siniga Dozza Lela Tohil Dian Erde Kourditi Eddeki Billi Chelle Tigui Arguei Bogarna Marfa Ache Forom Oye Yeska FADA Kazer Ehi Echinga Tangachinga Edri Boughi Loga Douourounga Karda Dourkou Bina Kossoumia Enneri Sao Doma Localités Enneri Akosmanoa Yarda Sol Sole Choudija Assoe Eberde Madadi Enneri Nei Tiouma Yarda Bedo Rou Abedake Oue-Oue Bidadi Chef-lieu de province 18°30'0"N -

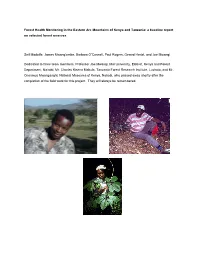

Forest Health Monitoring in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Kenya and Tanzania: a Baseline Report on Selected Forest Reserves

Forest Health Monitoring in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Kenya and Tanzania: a baseline report on selected forest reserves Seif Madoffe, James Mwang’ombe, Barbara O’Connell, Paul Rogers, Gerard Hertel, and Joe Mwangi Dedicated to three team members, Professor Joe Mwangi, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya and Forest Department, Nairobi; Mr. Charles Kisena Mabula, Tanzania Forest Research Institute, Lushoto, and Mr. Onesmus Mwanganghi, National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, who passed away shortly after the completion of the field work for this project. They will always be remembered. FHM EAM Baseline Report Acknowledgements Cooperating Agencies, Organizations, Institutions, and Individuals USDA Forest Service 1. Region 8, Forest Health Protection, Atlanta, GA – Denny Ward 2. Engineering (WO) – Chuck Dull 3. International Forestry (WO) – Marc Buccowich, Mellisa Othman, Cheryl Burlingame, Alex Moad 4. Remote Sensing Application Center, Salt Lake City, UT – Henry Lachowski, Vicky C. Johnson 5. Northeastern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA – Barbara O’Connell, Kathy Tillman 6. Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT – Paul Rogers 7. Northeastern Area, State & Private Forestry, Newtown Square, PA – Gerard Hertel US Agency for International Development 1. Washington Office – Mike Benge, Greg Booth, Carl Gallegos, Walter Knausenberger 2. Nairobi, Kenya – James Ndirangu 3. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – Dan Moore, Gilbert Kajuna Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania (Faculty of Forestry and Nature Conservation) – Seif Madoffe, R.C.