George Washington's Development As an Espionae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adversaries in a Cauldron

c01.qxd 09/29/03 11:15 AM Page 1 One Adversaries in a Cauldron On Broadway across from Bowling Green in New York City, Benedict Arnold, American turncoat and now a brigadier general in His Majesty’s Royal British Army, limped into British army headquarters. It was late November 1780. Arnold had been summoned by Sir Henry Clinton, fifty, command- ing general of the British forces in North America, to get his marching orders for a new attack on the rebels. This was to be Arnold’s first action against his former compatriots, and he had been urging Clinton to let him attack Philadelphia, a storehouse for vast quantities of military sup- plies and also the seat of the Continental Congress—those dozens of gallows-bait revolutionists whom Arnold hated so passionately. Such a military strike could entomb the revolution. Clinton had declined. Arnold then urged an attack in one of the southern states. Clinton had taken time to think it over. General Clinton was squirming in a military and political cauldron. Nearly six years after the American Revolution had begun, the British army seemed no closer to defeating the rebels. In fact, for two and a half years, since the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey, George Washington and his ragged band of starvelings had been waiting a few miles north on the Hudson highlands for Sir Henry to come out of his New York fortress to challenge them again on the battlefield. The two men sitting here across from each other were the very yin and yang of personalities: phlegmatic Sir Henry, the ever-planning, cau- tious, slow-to-move British career soldier; and mercurial Arnold, the ever- dangerous, explosive, militarily gifted Connecticut soldier, a legend even among British officers. -

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

CHAINING the HUDSON the Fight for the River in the American Revolution

CHAINING THE HUDSON The fight for the river in the American Revolution COLN DI Chaining the Hudson Relic of the Great Chain, 1863. Look back into History & you 11 find the Newe improvers in the art of War has allways had the advantage of their Enemys. —Captain Daniel Joy to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, January 16, 1776 Preserve the Materials necessary to a particular and clear History of the American Revolution. They will yield uncommon Entertainment to the inquisitive and curious, and at the same time afford the most useful! and important Lessons not only to our own posterity, but to all succeeding Generations. Governor John Hancock to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, September 28, 1781. Chaining the Hudson The Fight for the River in the American Revolution LINCOLN DIAMANT Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ii retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation: printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson : the fight for the river in the American Revolution / Lincoln Diamant.—Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Carol Pub. Group, 1994. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 (pbk.) 1. New York (State)—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 2. United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 3. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park. -

Jonathan Dayton: Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 301 516 SO 019 492 TITLE Jonathan Dayton: Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution. A Bicentennial Series No. 19. INSTITUTION Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO CNH- Pub -71 -19 Fip DATE 87 -NOTE 9p.; For other documents in this series, see ED 300 319-334 and SO 019 486-491. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; Colonial History (United States); Legislators; *Military Service; *Public Service; *Revolutionary War (United States) IDENTIFIERS Bicentenial; *Dayton (Jonathan); New Jersey; *Signers of the United States Constitution; United States Constitution ABSTRACT Jonathan Dayton's practical approach to government evolved out of his military experiences during the Revolutionary War, and he became a supporter for the equal representation of the small states. This booklet on Dayton is one in a series on Revolutionary War soldiers who signed the United States Constitution. It covers his early life, his military service from 1776 to 1783, and his public service to New Jersey as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and as a U.S. legislator. Personal data about Dayton and suggestions for further readings are also included. (DJC) *************************************************************k********* * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT Of EDUCATION Mk/ d EducationN Research and Improvisment:-, -

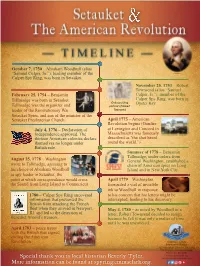

Special Thank You to Local Historian Beverly Tyler. More Information Can Be Found at Spyring.Emmaclark.Org

October 7, 1750 – Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper, Sr.”), leading member of the Culper Spy Ring, was born in Setauket. November 25, 1753 – Robert Townsend (alias “Samuel February 25, 1754 – Benjamin Culper, Jr.”), member of the Tallmadge was born in Setauket. Culper Spy Ring, was born in Only surviving Oyster Bay. Tallmadge was the organizer and portrait of Robert leader of the Revolutionary War Townsend Setauket Spies, and son of the minister of the Setauket Presbyterian Church. April 1775 – American Revolution begins (Gunfire July 4, 1776 – Declaration of at Lexington and Concord in Independence approved. The Massachusetts was famously thirteen American colonies declare described as "the shot heard themselves no longer under round the world.”) British rule. Summer of 1778 – Benjamin Tallmadge, under orders from August 25, 1778 – Washington General Washington, established a wrote to Tallmadge, agreeing to chain of American spies on Long his choice of Abraham Woodhull Island and in New York City. as spy leader in Setauket, the point at which correspondence would cross April 1779 – Washington the Sound from Long Island to Connecticut. forwarded a vial of invisible ink to Woodhull in response 1780 – Culper Spy Ring uncovered to his concern that his letters might be information that prevented the intercepted, leading to his discovery. British from attacking the French fleet when they arrived in Newport, May 4, 1780 – as noted by Woodhull in a RI. and led to the detection of letter, Robert Townsend decided to resign Benedict Arnold’s treason. because he felt it was only a matter of time until he was uncovered. -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

Draft Chapter

Ocean Special Area Management Plan Chapter 4: Cultural and Historic Resources Table of Contents 400 Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 410 Historic Contexts and Cultural Landscapes of the Ocean SAMP Area .......................4 410.1 Pre-Contact Geological History............................................................................5 410.2 Narragansett Tribal History.................................................................................6 410.3 European Exploration and Colonial Settlement Landscape Context .............16 410.4 Post-Colonial Cultural Landscape Context.......................................................18 410.5 Military Landscape Context ...............................................................................21 410.6 Fisheries Landscape Context ..............................................................................31 410.6.1 Rhode Island Fisheries.............................................................................31 410.6.2 Fishing and Subsistence on Block Island.................................................33 410.6.3 Historic Shipwrecks of Fishing Vessels ..................................................34 410.6.4 Historic Harbor Features..........................................................................35 410.7 Marine Transportation and Commercial Landscape Context ........................35 410.8 Recreation and Tourism Landscape Context....................................................38 -

The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 12 Number 3 Article 5 The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington. By Brad Meltzer and Josh Mensch, New York, N.Y.: Flatiron Books, 2019. Millard E. Moon Ed.D., Colonel (ret.) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 170-174 Recommended Citation Moon, Millard E. Ed.D., Colonel (ret.). "The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington. By Brad Meltzer and Josh Mensch, New York, N.Y.: Flatiron Books, 2019.." Journal of Strategic Security 12, no. 3 (2019) : 170-174. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.12.3.1767 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol12/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington. By Brad Meltzer and Josh Mensch, New York, N.Y.: Flatiron Books, 2019. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol12/iss3/5 Moon: The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington. B The First Conspiracy the Secret Plot to Kill George Washington. By Brad Meltzer and Josh Mensch, New York, N.Y.: Flatiron Books, 2019. ISBN: 978-1-250-13033-4, ISBN: 978-1-250-23122-2 (signed edition), ISBN: 978-1-250-13034-1 9 (ebook), Author’s Note, Notes on text, Cast of Characters, Notes, Selected Bibliography, Index, Pp. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 1, Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1 The American Revolution and the Post-Revolutionary Era: A Historical Legacy Introduction From 1774 to 1783, the British government and its upstart American colony became locked in an increasingly bitter struggle as the Americans moved from violent protest over British colonial policies to independence As this scenario developed, intelligence and counterintelligence played important roles in Americas fight for freedom and British efforts to save its empire It is apparent that British General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America since 1763, had good intelligence on the growing rebel movement in the Massachusetts colony prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concord His highest paid spy, Dr Benjamin Church, sat in the inner circle of the small group of men plotting against the British Gage failed miserably, however, in the covert action and counterintelligence fields Gages successor, General Howe, shunned the use of intelligence assets, which impacted significantly on the British efforts General Clinton, who replaced Howe, built an admirable espionage network but by then it was too late to prevent the American colonies from achieving their independence On the other hand, George Washington was a first class intelligence officer who placed great reliance on intelligence and kept a very personal hand on his intelligence operations Washington also made excellent use of offensive counterintelligence operations but never created a unit or organization to conduct defensive counterintelligence or to coordinate its -

Report To: Captain Carl I

THE TRUE BIRTHPLACE OF THE NAVY Page 1 By Bruce Campbell MacGunnigle Captain, RI Naval Militia; Colonel, RI Militia Preface In his 1974 book: Sea of Glory, A Naval History of the American Revolution, Nathan Miller writes in the preface: “Historians have lingered over the American Revolution, examining in exhaustive detail its military and political aspects, its diplomatic and social overtones. Yet the naval side of the conflict has been almost completely neglected… From the very beginning, the American War of Independence was a maritime conflict. The high-handed manner adopted by the Royal Navy in enforcing the laws against smuggling helped bring on the war… Britain had undisputed control of American waters and should have had no difficulty in snuffing out the rebellion by choking off the tools of war destined for the rebels from abroad. That this was not done was the result of muddled planning and the courage and skill of Yankee seamen.”1 Intent The intent of this study is to identify and examine all the claims made by various towns and regions to be the “Birthplace of the Navy” or the “First American Navy.” Definitions2 To identify and examine all the claims made by various towns and regions, we need to set parameters and exactly define what we‟re looking for. Since we‟re studying the “Birthplace of the Navy” or the “First American Navy” we need to define what a Navy is. Webster‟s definition of the word “Navy” is “A group of ships…” Just to be sure there is no confusion, Webster‟s definition of the word Group is: “Two or more…” 1 Miller, Nathan, Sea of Glory, A Naval History of the American Revolution, Charleston, SC, 1974, Preface, pp. -

Quartering, Disciplining, and Supplying the Army at Morristown

537/ / ^ ? ? ? QUARTERING, DISCIPLINING ,AND SUPPLYING THE ARMY AT MORRISTOWN, 1T79-1780 FEBRUARY 23, 1970 1VDRR 5 Cop, 2 1 1 ’ QUARTERING, DISCIPLINING, AND SUPPLYING THE ARMY FEBRUARY 23, 1970 U.S. DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR national park service WASHINGTON, D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................... i I. CIRCUMSTANCES LEADING TO THE MORRISTOWN ENCAMPMENT 1779-1780 .............................................. 1 II. QUARTERING OF THE ARMY AT MORRISTOWN,1779-1780 ......... 7 1. PREPARATION OF THE C A M P ............................. 7 2. COMPOSITION AND STRENGTH OF THE ARMY AT MORRISTOWN . 9 III. DAILY LIFE AT THE ENCAMPMENT............................... 32 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE ARMY OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.............................................. 32 2. ORGANIZATION OF THE CONTINENTAL A R M Y ................... 36 3. HEADQUARTERS: FORD MA NS IO N......................... 38 4. CONSTRUCTION OF THE C A M P ............................... 40 5. LIFE AT THE WINTER QUARTERS......................... 48 6. SOCIAL ACTIVITIES AT THE MORRISTOWN ENCAMPMENT .... 64 7. A MILITARY ENCOUNTER WITH THE E N E M Y ................ 84 IV. DISCIPLINE OF THE TROOPS AT MORRISTOWN.................... 95 1. NATURE OF MILITARY DISCIPLINE ....................... 95 2. LAXITY IN DISCIPLINE IN THE CONTINENTAL AR M Y ............ 99 3. OFFENSES COMMITTED DURING THE ENCAMPMENT ........... 102 V. SUPPLY OF THE ARMY AT MORRISTOWN.......................... 136 1. SUPPLY CONDITIONS PRIOR TO THE MORRISTOWN