Stealth and Secrecy: the Culper Spy Ring's Triumph Over the Tragedy Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spies That Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Lew, Masaki, "The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 19. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/19 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Humanities Western Civilization 102 March 16, 2020 1 Continental Spy Nathan Hale, standing below the gallows, spoke to his British captors with nothing less than unequivocal patriotism: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”1 American History idolizes Hale as a hero. His bravery as the first pioneer of American espionage willing to sacrifice his life for the growing colonial sentiment against a daunting global empire vindicates this. Yet, behind Hale’s success as an operative on -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge the Following Excerpts Were Prepared by Col

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge The following excerpts were prepared by Col. Benjamin Tallmadge THE SUBJECT OF THIS memoir was born at Brookhaven, on Long Island, in Suffolk county, State of New York, on the 25th of February, 1754. His father, the Rev. Benjamin Tallmadge, was the settle minister of that place, having married Miss Susannah Smith, the daughter of the Rev. John Smith, of White Plains, Westchester county, and State of New York, on the 16th of May, 1750. I remember my grandparents very well, having visited them often when I was young. Of their pedigree I know but little, but have heard my grandfather Tallmadge say that his father, with a brother, left England together, and came tot his country, one settling at East Hampton, on Long Island, and the other at Branford, in Connecticut. My father descended from the latter stock. My father was born at New Haven, in this State, January 1st, 1725, and graduated at Yale College, in the year 1747, and was ordained at Brookhaven, or Setauket, in the year 1753, where he remained during his life. He died at the same place on the 5th of February, 1786. My mother died April 21st, 1768, leaving the following children, viz.: William Tallmadge, born October 17, 1752, died in the British prison , 1776. Benjamin Tallmadge, born February 25, 1754, who writes this memoranda. Samuel Tallmadge, born November 23, 1755, died April 1, 1825. John Tallmadge, born September 19, 1757, died February 24, 1823. Isaac Tallmadge, born February 25, 1762. My honored father married, for his second wife, Miss Zipporah Strong, January 3rd, 1770, by whom he had no children. -

“Extracts from Some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing

1 “Extracts from some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing Joseph M. Adelman National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow American Antiquarian Society Presented to the Joint Seminar of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies And the Program in Early American Economy and Society, LCP Library Company of Philadelphia, 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia 24 February 2012 3-5 p.m. *** DRAFT: Please do not cite, quote, or distribute without permission of the author. *** 2 The eight years of the Revolutionary War were difficult for the printing trade. After over a decade of growth and increasing entanglement among printers as their networks evolved from commercial lifelines to the pathways of political protest, the fissures of the war dispersed printers geographically and cut them off from their peers. Maintaining commercial success became increasingly complicated as demand for printed matter dropped, except for government printing, and supply shortages crippled communications networks and hampered printers’ ability to produce and distribute anything that came off their presses. Yet even in their diminished state, printers and their networks remained central not only to keeping open lines of communication among governments, armies, and civilians, but also in shaping public opinion about the central ideological issues of the war, the outcomes of battles, and the meaning of events affecting the war in North America and throughout the Atlantic world. What happened to printers and their networks is of vital importance for understanding the Revolution. The texts that historians rely on, from Common Sense and The Crisis to rural newspapers, almanacs, and even diaries and correspondence, were shaped by the commercial and political forces that printers navigated as they produced printed matter that defined the scope of debate and the nature of the discussion about the war. -

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold Purpose By debating the legacy of Benedict Arnold, students will build reasoning and critical thinking skills and an understanding of the complexity of historical events and historical memory. Program Summary In this presentation, offered as a public program at the National Museum of American History from December 2010-April 2011, an actor portrays a fictionalized Benedict Arnold, hero and villain of the American Revolution. Arnold, in dialogue with an audience that is facilitated by an arbiter, discusses his notable actions at the Battle of Saratoga and at Valcour Island, as well as his decision to sell the plans for West Point to the British. At the conclusion of the program, audience members consider how history should remember Arnold, as a traitor, or as a hero. This set of materials is designed to provide you an opportunity to have a similar debate with your students. Included in this resource set are a full video of the program, to be used as preparation for the classroom activity, and Arnold’s conversation with the audience divided by theme, to be used with the resources offered below for your own Time Trial of Benedict Arnold. A full version of the program is available here. [https://vimeo.com/129257467] Grade levels 5-8 Time Three 45 minute periods National Standards National Center for History in the Schools: United States History Standards; Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s); Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society Common Core Standards for Literacy in History and Social Studies: Speaking and Listening Standards Comprehension and Collaboration, standard 1: Grades 6-8: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher- led) with diverse partners on grade level topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. -

Here, a Single Source Is the Only Witness

The Spy Who Never Was The Strange Case of John Honeyman and Revolutionary War Espionage Alexander Rose sion so gravely threaten the John Honeyman is famed as Revolution’s survival. the secret agent who saved George Washington and the The problem is, John Honey- Continental Army during the man was no spy—or at least, dismal winter of 1776/77. At a not one of Washington’s. In this time when Washington had suf- essay I will establish that the fered an agonizing succession of key parts of the story were defeats at the hands of the Brit- The problem is, John invented or plagiarized long “ ish, it was Honeyman who after the Revolution and, Honeyman was no brought the beleaguered com- through repetition, have spy.…Key parts of his mander precise details of the become accepted truth. I exam- story were invented…and Hessian enemy’s dispositions at ine our knowledge of the tale, through repetition have Trenton, New Jersey. assess the veracity of its compo- become accepted truth. nents, and trace its DNA to the Soon afterwards, acting his single story—a piece of family part as double agent, Honey- history published nearly 100 man informed the gullible Col. years after the battle. 1 These Johann Rall, the Hessian com- historical explorations addition- ” ally will remind modern intelli- mander, that the colonials were in no shape to attack. Washing- gence officers and analysts that ton’s men, he said, were suffer- the undeclared motives of ing dreadfully from the cold and human sources may be as many were unshod. -

The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty

1 Matt Gillespie 12/17/03 A&HW 4036 Unit: Colonial America and the American Revolution. Lesson: The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty. AIM: Why was the American victory at the Saratoga Campaign important for the American Revolution? Goals/Objectives: 1. Given factual data about the Battle of Saratoga and the Battle of Yorktown, students will be able to describe the particular events of the battles and how the Americans were able to win each battle. 2. Students will be able to recognize and explain why the battles were significant in the context of the entire war. (For example, the Battle of Saratoga indirectly leads to French assistance.) 3. Students will be able to read and interpret a key political document, The Paris peace Treaty of 1783. 4. Students will investigate key turning points in US history and explain why these events are significant. Students will be able to make arguments as to why these two battles were turning points in American history. (NYS 1.4) 5. Given the information, students will understand their historical roots and be able to reconstruct the past. Students will be able to realize how victory in these battles enabled the paris Peace Treaty to come about. (NCSS II) Main Ideas: • The campaign consists of three major conflicts. 1) The Battle of Freeman’s farm. 2) Battle of Bennington. 3) Battle of Bemis Heights. • Battle of Bennington took place on Aug. 16-17th, 1777. Burgoyne sent out Baum to take American stores at Bennington. General Stark won. • Freeman’s farm was on Sept. -

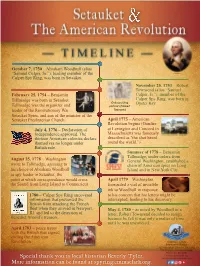

Special Thank You to Local Historian Beverly Tyler. More Information Can Be Found at Spyring.Emmaclark.Org

October 7, 1750 – Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper, Sr.”), leading member of the Culper Spy Ring, was born in Setauket. November 25, 1753 – Robert Townsend (alias “Samuel February 25, 1754 – Benjamin Culper, Jr.”), member of the Tallmadge was born in Setauket. Culper Spy Ring, was born in Only surviving Oyster Bay. Tallmadge was the organizer and portrait of Robert leader of the Revolutionary War Townsend Setauket Spies, and son of the minister of the Setauket Presbyterian Church. April 1775 – American Revolution begins (Gunfire July 4, 1776 – Declaration of at Lexington and Concord in Independence approved. The Massachusetts was famously thirteen American colonies declare described as "the shot heard themselves no longer under round the world.”) British rule. Summer of 1778 – Benjamin Tallmadge, under orders from August 25, 1778 – Washington General Washington, established a wrote to Tallmadge, agreeing to chain of American spies on Long his choice of Abraham Woodhull Island and in New York City. as spy leader in Setauket, the point at which correspondence would cross April 1779 – Washington the Sound from Long Island to Connecticut. forwarded a vial of invisible ink to Woodhull in response 1780 – Culper Spy Ring uncovered to his concern that his letters might be information that prevented the intercepted, leading to his discovery. British from attacking the French fleet when they arrived in Newport, May 4, 1780 – as noted by Woodhull in a RI. and led to the detection of letter, Robert Townsend decided to resign Benedict Arnold’s treason. because he felt it was only a matter of time until he was uncovered. -

Coventry Birthplace of Nathan Hale

Historic Coventry is the gateway to Northeast Connecti- In its aim to cherish history, This town is ideal for all ages. Patriots cut’s Quiet Corner. Spread over 37 square miles of Coventry honors its heroes. Park and Lake Wangumbaug are family Welcome woods and old farmlands, our town of 12,500 offers The Vietnam Veteran’s favorites. Patriot’s Park on Lake Street historic sites, farms, antique and specialty shops, public Memorial located on the is an excellent area for retreats and beaches, delicious restaurants, cozy bed-and-breakfast Veteran’s Memorial Green family events, with a guarded beach for to inns, a state boat launch, and an acclaimed farmers’ mar- on Lake Street, honors the swimming, playground, picnic area, ket. 612 Connecticut military personnel who gave their life Community Center and band shell for during the conflict. summer concerts. Lake Wangumbaug Coventry, incorporated in is a popular destination for fishing, Coventry 1712, boasts a wealth of his- History goes hand-in-hand boating, and water sports. Visitors and tory that is rooted in the hero- with agriculture in Coventry. residents can soak up the sunshine outdoors at Coventry’s ic life and death of Connecti- The plethora of farms and two 18-hole golf courses or the several walking trails cut’s state hero, Nathan Hale. local businesses highlight throughout town. His patriotism during the Coventry’s agricultural herit- American Revolution is cele- age. From the locally- brated at several events held throughout the year at Hale produced wines at Cassidy Homestead, the birthplace of Nathan Hale. The Hale For more information on Coventry Homestead, built in 1776, is now an operating museum Hill Vineyard to the organic herbs at Topmost Herb Farm, and its surrounding region, stop by educating visitors from near and far about the famous Coventry covers it all. -

Inquiry – Benedict Arnold

Inquiry – Benedict Arnold Hook discussion question: What is betrayal? The discussion must touch on themes of loyalty and trust. Other themes may include ethics and morality. Hook visual: Presentation formula Previous Unit: The Revolutionary War will be in progress. Saratoga (1777) should have been covered. This Unit: Narrative story to present a skeletal overview of the events. Then introduce the documents, to add “muscle” to the events. Next Unit: The Revolutionary War topic will continue and be brought to conclusion. Post-Lesson Discussion prompts 1. How should we go about weighing the good someone does against the bad? At what point is one (good/bad) not balanced by the other? 2. After the war, for what reasons might the British trust or not trust Benedict Arnold? 3. In the years following the war, America tried to get England to hand over Benedict Arnold to American authorities. Should the British give him up? Why yes/no? 4. One thing missing from the discussion of betrayal and loyalty is the concept of regret. How might this relate to Arnold, Washington and others, and by what means might it be expressed? 5. How likely (or not) would it be today for one of America’s top Generals to engage in a similar traitorous act? 6. To what extent would it matter if it is a General betraying the country or a civilian acting in a traitorous manner…should these be viewed in a similar light? 7. To what extent can a person be trusted again once they have already broken your trust? 8. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 21

K<^' ^ V*^'\^^^ '\'*'^^*/ \'^^-\^^^'^ V' ar* ^ ^^» "w^^^O^o a • <L^ (r> ***^^^>^^* '^ "h. ' ^./ ^^0^ Digitized by the internet Archive > ,/- in 2008 with funding from ' A^' ^^ *: '^^'& : The Library of Congress r^ .-?,'^ httpy/www.archive.org/details/pewyorkgepealog21 newy THE NEW YORK Genealogical\nd Biographical Record. DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XXL, 1890. 868; PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY, Berkeley Lyceuim, No. 23 West 44TH Street, NEW YORK CITY. 4125 PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Rev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS, Chairman. Dr. SAMUEL S. PURPLE.. Gen. JAS. GRANT WILSON. Mr. THOS. G. EVANS. Mr. EDWARD F. DE LANCEY. Mr. WILLL\M P. ROBINSON. Press of J. J. Little & Co., Astor Place, New York. INDEX OF SUBJECTS. Albany and New York Records, 170. Baird, Charles W., Sketch of, 147. Bidwell, Marshal] S., Memoir of, i. Brookhaven Epitaphs, 63. Cleveland, Edmund J. Captain Alexander Forbes and his Descendants, 159. Crispell Family, 83. De Lancey, Edward F. Memoir of Marshall S. Bidwell, i. De Witt Family, 185. Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Edsall, Thomas H. Inscriptions from the Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Evans, Thomas G. The Crispell Family, 83. The De Witt Family, 185. Fernow, Berlhold. Albany and New York Records, 170 Fishkill and its Ancient Church, 52. Forbes, Alexander, 159. Heermans Family, 58. Herbert and Morgan Records, 40. Hoes, R. R. The Negro Plot of 1712, 162. Hopkins, Woolsey R Two Old New York Houses, 168. Inscriptions from Morgan Manor, N. J. , 112. John Hart, the Signer, 36. John Patterson, by William Henry Lee, 99. Jones, William Alfred. The East in New York, 43. Kelby, William. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights.