Monograph-Ana Catalina Ramirez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

University of Pittsburgh Winter 2012 • 71 Center for Latin American Studies

Winter 2012 • 71 CLASicos Center for Latin American Studies University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh 2 The Latin American CLASicos • Winter 2012 Archaeology Program Latin America has been the principal geographical focus of archaeology at the University of Pittsburgh over the last two decades. Administered by the Department of Anthropolo- gy, with the cooperation and support of CLAS, the Latin American Archaeology Pro- gram involves research, training, and publication. Its objective is to maintain an interna- tional community of archaeology graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. This objective is promoted in part through fellowships for outstanding graduate students to study any area of Latin American prehistory. Many of these fellowships are awarded to students from Latin America (nearly half of the students in the program). The commit- ment to Latin American archaeology also is illustrated by collaborative ties with numer- ous Latin American institutions and by the bilingual publication series, which makes the results of primary field research available to a worldwide audience. The Latin American Archaeology Publications Program publishes the bilingual From 1997—Left to right: Latin American Archaeology Fellows Hope Henderson (US), María Auxiliadora Cordero (Ecuador), Ana María Boada (Colombia), [Professor Dick Drennan], and Rafael Gassón (Venezuela). Memoirs in Latin American Archaeology and Latin American Archaeology Reports, co-publishes the collaborative series Arqueología de México, and distributes internationally volumes on Latin American archaeology and related subjects from more than eighteen publishers worldwide. The Latin American Archaeology Database is on line, with datasets that complement the Memoirs and Reports series as well as disserta- tions and other publications. -

TRAINED ABROAD: a HISTORY of MULTICULTURALISM in COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by I

Trained Abroad: A History of Multiculturalism in Costa Rican Vocal Music Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ortiz Castro, Ivette Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 10:27:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/621142 TRAINED ABROAD: A HISTORY OF MULTICULTURALISM IN COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by Ivette Ortiz Castro _______________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Ivette Ortiz-Castro, titled Trained abroad: a history of multiculturalism in Costa Rican vocal music and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Kristin Dauphinais ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Jay Rosenblatt ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 William Andrew Stuckey Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

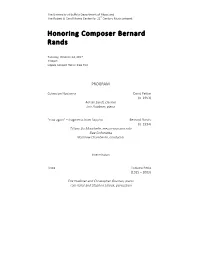

PRINTABLE PROGRAM Bernard Rands

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Honoring Composer Bernard Rands Tuesday, October 24, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Coleccion Nocturna David Felder (b. 1953) Adrián Sandí, clarinet Eric Huebner, piano "now again" – fragments from Sappho Bernard Rands (b. 1934) Tiffany Du Mouchelle, mezzo-soprano solo Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Intermission Linea Luciano Berio (1925 – 2003) Eric Huebner and Christopher Guzman, piano Tom Kolor and Stephen Solook, percussion Folk Songs Bernard Rands I. Missus Murphy’s Chowder II. The Water is Wide III. Mi Hamaca IV. Dafydd Y Garreg Wen V. On Ilkley Moor Baht ‘At VI. I Died for Love VII. Über d’ Alma VIII. Ar Hyd y Nos IX. La Vera Sorrentina Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Emlyn Johnson, flute Erin Lensing, oboe Adrián Sandí, clarinet Michael Tumiel, clarinet Jon Nelson, trumpet Kristen Theriault, harp Eric Huebner, piano Chris Guzman, piano Tom Kolor, percussion Steve Solook, percussion Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano (solo) Julia Cordani, soprano Minxin She, alto Hanna Hurwitz, violin Victor Lowrie, viola Katie Weissman, ‘cello About Bernard Rands Through a catalog of more than a hundred published works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure in contemporary music. His work Canti del Sole, premiered by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta, and the New York Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral suites Le Tambourin, won the 1986 Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. His work Canti d'Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy award in 2000. -

Costa Rica PR Country Landscape 2011

Costa Rica PR Country Landscape 2011 Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management ● ● ● ● Acknowledgements Produced by: Lauren E. Bonello, senior public relations student at the Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications, and master’s of science in Management student at the Hough Graduate School of Business, University of Florida (UF); Vanessa Bravo, doctoral candidate at the UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications, and Fulbright master’s of arts in Mass Communications, University of Florida; and Monica Morales, Fulbright master’s student at the UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications. Supervised and guided by: Juan-Carlos Molleda, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator, UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications and Coordinator of the GA Landscape Project. Read and approved by: John Paluszek, Senior Counsel of Ketchum and 2010-2012 Chair of the Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management. Revised & signed off by: Carmen Mayela Fallas, president of Comunicación Corporativa Ketchum. Date of completion: April 2011. Public Relations Industry Brief History Latin American Origins Latin American studies about the origins of public relations in the continent establish a common denominator as to the source of the practice in the region. Costa Rica is no exception, and this common denominator plays a relatively important goal in the development and establishment not only in the country, but also for Central America in particular. According to early registries, the genesis of public relations in Latin America is closely related to the introduction of foreign companies, which were used to having public relations as part of their businesses, into the local economies (Molleda & Moreno, 2008). -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 Online, Summer 2015

Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Summer 2015: Volume 31, Online Issue p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 In Memoriam Joseph de Pasquale Remembered p. 11 Recalling the AVS Newsletter: English Viola Music Before 1937 In recalling 30 years of this journal, we provide a nod to its predecessor with a reprint of a 1976 article by Thomas Tatton, followed by a brief reflection by the author. Feature Article p. 13 Concerto for Viola Sobre un Canto Bribri by Costa Rican composer Benjamín Gutiérrez Or quídea Guandique provides a detailed look at the first viola concerto of Costa Rica, and how the country’s history influenced its creation. Departments p. 25 In the Studio: Thought Multi-Tasking (or What I Learned about Painting from Playing the Viola) Katrin Meidell discussed the influence of viola technique and pedagogy in unexpected areas of life. p. 29 With Viola in Hand: Experiencing the Viola in Hindustani Classical Music: Gisa Jähnichen, Chinthaka P. Meddegoda, and Ruwin R. Dias experiment with finding a place for the viola in place of the violin in Hindustani classical music. On the Covers: 30 Years of JAVS Covers compiled by Andrew Filmer and David Bynog Editor: Andrew Filmer The Journal of the American Viola Society is Associate Editor: David M. Bynog published in spring and fall and as an online- only issue in summer. The American Viola Departmental Editors: Society is a nonprofit organization of viola At the Grassroots: Christine Rutledge enthusiasts, including students, performers, The Eclectic Violist: David Wallace teachers, scholars, composers, makers, and Fresh Faces: Lembi Veskimets friends, who seek to encourage excellence in In the Studio: Katherine Lewis performance, pedagogy, research, composition, New Music Reviews: Andrew Braddock and lutherie. -

Clarinet Lesson/Clinic Sheet

Clarinet Resources Jonathan Bouchard | jonbouchard.com Beginner Level and Second Level – Method Books Practice Tools - Clarinet Method (Galper) - Mirror - So You Want to Play The Clarinet (Paula Corley) - Tuner - Clarinet Basics (Paul Harris) - metronome - Clarinet For Beginners (Galper) - Essential Elements 2000: Bb clarinet Book Mouthpieces - Standard of Excellence (Bruce Pearson) - D'Addario Reserve As students advance here are some options to think about: - Selmer Concept Scale Books: - Vandoren B45 - Royal Conservatory of Music Clarient Technique - 24 Varied Scale Exercises for Clarinet (J.B. Albert) Reeds - Clarinet Scales and Arpeggios (Galper) Vandoren 2.5-3.5 D’Addario Reserve 2.5-3.5 Etudes - Starter Studies (Philip Sparke) Clarinets - Skillful Studies (Philip Sparke) Yamaha, Selmer Henri - 60 Rambles (Leon Lester) Paris, and Buffet are good - Duettist Folio (Voxmann) and reliable instrument - Royal Conservatory Preparatory – Grade 4 Etudes manufacturers - Starter Duets (Philip Sparke) - Skillful Duets (Philip Sparke) Classical Clarinetists Jazz Clarinetists - Improve Your Sight Reading (Paul Harris) Martin Frost Paquito D’rivera - Velocity Studies for the Clarinet (Opperman) Sabine Meyer Anat Cohen Suggested Repertoire Julian Bliss Benny Goodman Richard Stoltzman Artie Shaw - Clarinet Solos (Nylo Hovie) Sharon Kam Victor Goines - Solos for Clarinet Playing (Christmen) - Gypsy Moods - Clasical Album (Arthur Wilner) Recommended Listening - Rubank Book of Classical Solos Mozart: Clarinet Concerto in A major, K622 - Original Clarinet -

Clarinet Concertos Clarinet

Clarinet 14CD Concertos 95787 ClaRINet Concertos 14CD CD1 Molter Concertos Nos. 1–5 CD9 Mercadante Concertino Concertos Nos. 1 & 2 CD2 Spohr Concertos Nos. 1 & 4 Sinfonia concertante No.3 CD3 Spohr Concertos Nos. 2 & 3 CD10 Hoffmeister Concerto CD4 Mozart Concerto in A K622 Sinfonie concertanti Nos. 1 & 2 Bruch Clarinet & Viola Concerto CD11 Baermann Concertstück in G minor CD5 Weber Concertino Clarinet Concertinos Opp. 27 & 29 Concertos Nos. 1 & 2 Sonata No.3 in D minor/F Busoni Concertino CD12 Finzi Concerto CD6 Crusell Concertos Nos. 1–3 Stanford Concerto Copland Concerto (1948 version) CD7 Krommer Concerto Op.36 Double Concertos Opp. 35 & 91 CD13 Nielsen Concerto Tansman Concerto Stamitz CD8 Concerto No.1 Hindemith Concerto Double Concerto Clarinet & Bassoon Concerto CD14 Rietz Concerto Rossini Introduction, theme & variations Mendelssohn Concert Pieces Opp. 113 & 114 Performers include: Davide Bandieri · Kevin Banks · Kálmán Berkes · Per Billman Jean-Marc Fessard · Henk de Graaf · Sharon Kam · Dieter Klöcker · Sebastian Manz Oskar Michallik · Robert Plane · Giuseppe Porgo · Giovanni Punzi · David Singer Tomoko Takashima · Maria du Toit · Kaori Tsutsui · Eddy Vanoosthuyse C 2018 Brilliant Classics DDD/ADD STEMRA Manufactured and printed in the EU 95787 www.brilliantclassics.com Clarinet 14CD Concertos 95787 Clarinet Concertos historical interest. The solo writing – composed for a high clarinet in D – suggests the virtuosity of Most musical instruments in use today derive from very ancient ancestors. The oboe, for example, a coloratura soprano. may be traced back to the shawm, an instrument with a double-reed and wooden mouthpiece, Louis Spohr (1784–1859), born in Brunswick, established a reputation as a violinist and conductor, used from the 12th century onwards. -

Costa Rican MUSIC

Costa Rican MUSIC A small peek into the culture that fills the air of Costa Rica . By Trent Cronin During my time spent in the country of Costa Rica, I found a lot of PURA VIDA different sounds that catch your ear while you are in Costa Rica. After sorting This is a picture of a guy through the honking horns and barking dogs, you’ll find two types of music. I met named Jorge; he These two types of music are the traditional Latin American music and the more works at the airport in modern, or Mainstream, music that we are familiar with in the States. The Latin Heredia. He was telling American music includes some well-known instruments like the guitar, maracas, some me that music is in his veins. This is a good type of wind instrument (sometimes an ocarina) and the occasional xylophone. The example of how every music style tends to be very up beat and gives of a happy vibe, although there are Costa Rican holds some sad songs. Sometimes, in the larger, more populated, parts of the city, you can music near and dear to find one or more street performers playing this type of music. I don’t know what it is their heart. about hearing someone sing in a foreign language, but I like it. I will admit; I was a little surprised to walk passed a car and hear Beyonce’ being played. After further time spent I found out that other famous music artist like Metallica, The Beatles, Michael Jackson, and Credence Clear Water Revival (CCR) have diffused into the radio waves of Costa Rica. -

TRIO Kam Porat

TRIO KaM PORaT MI 13.11.2019 THEaTERfORuM PRoGRAMM MITTWocH 13. NoVEMBER 2019 DIE AUSFüHRENDEN WOlfGaNG aMaDEus MOZaRT [1756 – 1791] sHaRON KaM, Klarinette 1998 für ihre Weber-Aufnahme mit dem Gewandhausorchester Trio Es-Dur für Klarinette, Viola und Klavier KV 498, „Kegelstatt Trio“ (1786) Direkt nach der Sharon Kam gehört zu den weltweit führenden Klarinettistinnen Leipzig unter Kurt Masur sowie 2006 für ihre cD mit dem MDR Andante | Menuetto – Trio | Rondo. Allegretto Veranstaltung schreibt und arbeitet mit den bedeutendsten orchestern in den USA, Sinfonieorchester und Werken von Spohr, Weber, Rossini und der Musikjournalist Europa und Japan. Bereits mit 16 Jahren interpretierte sie Mendelssohn. Die Aufnahme „American classics“ mit dem Lon - ROBERT sCHuMaNN [1810 – 1856] Reinhard Palmer eine Mozarts Klarinettenkonzert in ihrem orchesterdebüt mit dem don Symphony orchestra unter der Leitung ihres Ehemannes „Märchenerzählungen“ für Klarinette, Viola und Klavier op. 132 (1853) Kritik zum Konzert. Israel Philharmonic orchestra unter Zubin Mehta, wenig später Gregor Bühl bekam den Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik. Lebhaft, nicht zu schnell | Lebhaft und sehr markiert | Ruhiges Tempo mit zartem Ausdruck | Sie können diese bereits Mozarts Klarinettenquintett mit dem Guarneri Quartet in New 2013 folgte ihre gefeierte „opera!“-cD für Klarinette und Lebhaft, sehr markiert am nächsten Mittag York. Zu Mozarts 250. Geburtstag spielte sie das Klarinetten - Kammerorchester mit Transkriptionen italienischer Arien. PAUSE unter konzert im Ständetheater in Prag, vom Fernsehen live in 33 Zum 100. Todestag von Max Reger veröffentlichte Sharon Kam www.theaterforum.de Länder übertragen. Beide Werke nahm sie mit der Bassett- die Klarinettenquintette von Reger und Brahms. In der Saison JOHaNNEs BRaHMs [1833 – 1897] bzw. -

Závěrečné Práce

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra dechových nástrojů Hra na klarinet Umělec pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy Diplomová práce Autor práce: Jakub Hrdlička Vedoucí práce: doc. Milan Polák Oponent práce: doc. Vít Spilka Brno 2015 Bibliografický záznam HRDLIČKA, Jakub. Umělec a pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy [Artist educator Charles Neidich and his influence on the American Clarinet school] Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra dechových nástrojů, 2015 doc. Milan Polák s. [69] Anotace Diplomová práce Umělec a pedagog Charles Neidich a jeho vliv na vývoj americké klarinetové školy pojednává o osobnosti Charlese Neidicha. Práce je rozdělena do několika částí, ve kterých se zaměřuji na americkou klarinetovou školu, Ch. N. jako umělce a pedagoga a v další fázi analýzu a popis jeho metodiky a rozhovor s nejúspěšnějšími žáky. Annotation Diploma thesis „Artist educator Charles Neidich and his influence on the American Clarinet school” deals with personality of Charles Neidich. The work is divided into several sections in which I focus on American Clarinet school, Ch. N. as an artist and educator and in the next phase analyze and description of his pedagogical methods and interview with the most renowned students. Klíčová slova Americká klarinetová škola, Charles Neidich, umělec, pedagog Keywords American clarinet school, Charles Neidich, artist, educator Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. Jakub Hrdlička V Brně dne 14. 8. 2015 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval docentu Milanu Polákovi za laskavou spolupráci při tvorbě této práce a také umělcům Mate Bekavac, Sharon Kam, Kari Kriikku za poskytnutí rozhovorů. -

Costa Rican Composer Benjamín Gutiérrez and His Piano Works

ANDRADE, JUAN PABLO, D.M.A. Costa Rican Composer Benjamín Gutiérrez and his Piano Works. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 158 pp. The purpose of this study is to research the life and work of Costa Rican composer Benjamín Gutiérrez (b.1937), with particular emphasis on his solo piano works. Although comprised of a small number of pieces, his piano output is an excellent representation of his musical style. Gutiérrez is regarded as one of Costa Rica’s most prominent composers, and has been the recipient of countless awards and distinctions. His works are known beyond Costa Rican borders only to a limited extent; thus one of the goals of this investigation is to make his music more readily known and accessible for those interested in studying it further. The specific works studied in this project are his Toccata y Fuga, his lengthiest work for the piano, written in 1959; then five shorter pieces written between 1981 and 1992, namely Ronda Enarmónica, Invención, Añoranza, Preludio para la Danza de la Pena Negra and Danza de la Pena Negra. The study examines Gutiérrez’s musical style in the piano works and explores several relevant issues, such as his relationship to nationalistic or indigenous sources, his individual use of musical borrowing, and his stance toward tonality/atonality. He emerges as a composer whose aesthetic roots are firmly planted in Europe, with strong influence from nineteenth-century Romantics such as Chopin and Tchaikovsky, but also the “modernists” Bartók, Prokofiev, Milhaud, and Ginastera, the last two of whom were Gutiérrez’s teachers. The research is divided into six chapters, comprising an introduction, an overview of the development of art music in Costa Rica, a biography of Gutiérrez, a brief account of piano music in the country before Gutiérrez and up to the present day, a detailed study of his solo piano compositions, and conclusions.