Costa Rica PR Country Landscape 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Costa Rica: Coyuntura Electoral Y Medios De Comunicación Elecciones 2014 San José, Costa Rica 2015 MEMORIA

Costa Rica: Coyuntura electoral y medios de comunicación Elecciones 2014 San José, Costa Rica 2015 MEMORIA Libertad de expresión, derecho a la información y opinión pública 324.730.972.86 C837c Costa Rica : coyuntura electoral y medios de comunicación : elecciones 2014 : memoria. – San José, C.R. : CICOM, 2015. 1 recurso en línea (141 p.). : il., digital, archivo PDF; .1 MB Requisitos del sistema: Adobe digital editors—Forma de acceso: World Wide Web ISBN 978-9968-919-16-6 1. ELECCIONES – COSTA RICA – 2014. 2. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN DE MASAS – ASPECTOS POLÍTICOS – COSTA RICA. 3. COMUNICACIÓN EN POLÍTICA – COSTA RICA. 4. POLÍTICA Y MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN DE MASAS – COSTA RICA. 5. ANÁLISIS DEL DISCURSO – ASPECTOS POLÍTICOS – COSTA RICA. 6. PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA. CIP/2834 CC/SIBDI. UCR Universidad de Costa Rica © CICOM Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio. Costa Rica. Primera edición: 2015 Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial. Todos los derechos reservados. Hecho el depósito de ley. ÍNDICE ÍNDICE ........................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................................................... 3 DERECHOS COMUNICATIVOS Y ELECCIONES NACIONALES ......................................... 5 Licda Giselle Boza Solano PRODUCCIÓN Y REPRODUCCIÓN DE CONTENIDOS EN FACEBOOK COMO HERRAMIENTA DE CONSTRUCCIÓN DE IDENTIDAD, Y SUS APLICACIONES EN INVESTIGACIÓN, EN EL CONTEXTO -

Monograph-Ana Catalina Ramirez

COSTA RICAN COMPOSER CARLOS ESCALANTE MACAYA AND HIS CONCERTO FOR CLARINET AND STRINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Ana Catalina Ramírez Castrillo May, 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Cynthia Folio, Advisory Chair, Music Studies Department (Music Theory) Dr. Charles Abramovic, Piano Department, Keyboard Department (Piano) Dr. Emily Threinen, Instrumental Studies Department (Winds and Brass) Dr. Stephen Willier, Music Studies Department (Music History) ABSTRACT The purpose of this monograph is to promote Costa Rican academic music by focusing on Costa Rican composer Carlos Escalante Macaya and his Concerto for Clarinet and Strings (2012). I hope to contribute to the international view of Latin American composition and to promote Costa Rican artistic and cultural productions abroad with a study of the Concerto for Clarinet and Strings (Escalante’s first venture into the concerto genre), examining in close detail its melodic, rhythmic and harmonic treatment as well as influences from different genres and styles. The monograph will also include a historical context of Costa Rican musical history, a brief discussion of previous important Costa Rican composers for the clarinet, a short analysis of the composer’s own previous work for the instrument (Ricercare for Solo Clarinet) and performance notes. Also, in addition to the publication and audio/video recording of the clarinet concerto, this document will serve as a resource for clarinet soloists around the world. Carlos Escalante Macaya (b. 1968) is widely recognized in Costa Rica as a successful composer. His works are currently performed year-round in diverse performance venues in the country. -

University of Pittsburgh Winter 2012 • 71 Center for Latin American Studies

Winter 2012 • 71 CLASicos Center for Latin American Studies University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh 2 The Latin American CLASicos • Winter 2012 Archaeology Program Latin America has been the principal geographical focus of archaeology at the University of Pittsburgh over the last two decades. Administered by the Department of Anthropolo- gy, with the cooperation and support of CLAS, the Latin American Archaeology Pro- gram involves research, training, and publication. Its objective is to maintain an interna- tional community of archaeology graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. This objective is promoted in part through fellowships for outstanding graduate students to study any area of Latin American prehistory. Many of these fellowships are awarded to students from Latin America (nearly half of the students in the program). The commit- ment to Latin American archaeology also is illustrated by collaborative ties with numer- ous Latin American institutions and by the bilingual publication series, which makes the results of primary field research available to a worldwide audience. The Latin American Archaeology Publications Program publishes the bilingual From 1997—Left to right: Latin American Archaeology Fellows Hope Henderson (US), María Auxiliadora Cordero (Ecuador), Ana María Boada (Colombia), [Professor Dick Drennan], and Rafael Gassón (Venezuela). Memoirs in Latin American Archaeology and Latin American Archaeology Reports, co-publishes the collaborative series Arqueología de México, and distributes internationally volumes on Latin American archaeology and related subjects from more than eighteen publishers worldwide. The Latin American Archaeology Database is on line, with datasets that complement the Memoirs and Reports series as well as disserta- tions and other publications. -

TRAINED ABROAD: a HISTORY of MULTICULTURALISM in COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by I

Trained Abroad: A History of Multiculturalism in Costa Rican Vocal Music Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ortiz Castro, Ivette Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 10:27:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/621142 TRAINED ABROAD: A HISTORY OF MULTICULTURALISM IN COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by Ivette Ortiz Castro _______________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Ivette Ortiz-Castro, titled Trained abroad: a history of multiculturalism in Costa Rican vocal music and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Kristin Dauphinais ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Jay Rosenblatt ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 William Andrew Stuckey Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v. -

The Political Culture of Democracy in Costa Rica, 2004

The Political Culture of Democracy in Costa Rica, 2004 Jorge Vargas-Cullell, CCP Luis Rosero-Bixby, CCP With the collaboration of Auria Villalta Ericka Méndez Mitchell A. Seligson Scientific Coordinator and Editor of the Series Vanderbilt University This publication was made possible through support provided by the USAID Missions in Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama. Support was also provided by the Office of Regional Sustainable Development, Democracy and Human Rights Division, Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the Office of Democracy and Governance, Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance, U.S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of Task Order Contract No. AEP-I-12-99-00041-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... i List of Tables and Figures........................................................................................................... iii List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................iii List of Figures.......................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms.................................................................................................................................... -

Listado De Canales Tv Prime Plus

Listado de Canales Tv Prime Plus ARGENTINA AR | TELEFE *FHD BR | TELECINE CULT *HD BR | DISNEY JUNIOR *HD CA | PBS Buffalo (WNED) AR | AMERICA 24 *FHD AR | TELEFE *HD BR | TELECINE ACTION *HD BR | DISNEY CHANNEL *HD CA | OWN AR | AMERICA 24 *HD AR | TELEFE *HD BR | TCM *HD BR | DISCOVERY WORLD *HD CA | OMNI_2 AR | AMERICA TV *FHD AR | TELEMAX *HD BR | TBS *HD BR | DISCOVERY TURBO *HD CA | OMNI_1 AR | AMERICA TV *HD AR | TELESUR *HD BR | SYFY *HD BR | DISCOVERY THEATHER *HD CA | OLN AR | AMERICA TV *HD | op2 AR | TN *HD BR | STUDIO UNIVERSAL *HD BR | DISCOVERY SCIENCE *HD CA | CablePulse 24 AR | C5N *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *FHD BR | SPACE *HD BR | DISCOVERY KIDS *HD CA | NBA_TV AR | C5N *HD | op2 AR | TV PUBLICA *HD BR | SONY *HD BR | DISCOVERY ID *HD CA | NAT_GEO AR | CANAL 21 *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *HD | op2 BR | REDE VIDA *HD BR | DISCOVERY H&H *HD CA | MUCH_MUSIC AR | CANAL 26 *HD AR | TV5 *HD BR | REDE TV *HD BR | DISCOVERY CIVILIZATION *HD CA | MTV AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TVE *HD BR | REDE BRASIL *HD BR | DISCOVERY CH. *HD CA | Makeful AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | VOLVER *HD BR | RECORD NEWS *HD BR | COMEDY CENTRAL *HD CA | HLN AR | CANAL DE LA CIUDAD *HD BR | RECORD *HD BR | COMBATE *HD CA | History Channel AR | CANAL DE LA MUSICA *HD BOLIVIA BR | PLAY TV *HD BR | CINEMAX *HD CA | GOLF AR | CINE AR *HD BO | ATB BR | PARAMOUNT *HD BR | CARTOON NETWORK *HD CA | Global Toronto (CIII) AR | CINE AR *HD BO | BOLIVIA TV BR | NICKELODEON *HD BR | CANAL BRASIL *HD CA | Game TV AR | CIUDAD MAGAZINE *HD BO | BOLIVISION *HD BR | NICK JR -

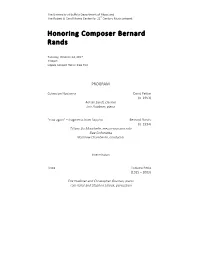

PRINTABLE PROGRAM Bernard Rands

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Honoring Composer Bernard Rands Tuesday, October 24, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Coleccion Nocturna David Felder (b. 1953) Adrián Sandí, clarinet Eric Huebner, piano "now again" – fragments from Sappho Bernard Rands (b. 1934) Tiffany Du Mouchelle, mezzo-soprano solo Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Intermission Linea Luciano Berio (1925 – 2003) Eric Huebner and Christopher Guzman, piano Tom Kolor and Stephen Solook, percussion Folk Songs Bernard Rands I. Missus Murphy’s Chowder II. The Water is Wide III. Mi Hamaca IV. Dafydd Y Garreg Wen V. On Ilkley Moor Baht ‘At VI. I Died for Love VII. Über d’ Alma VIII. Ar Hyd y Nos IX. La Vera Sorrentina Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Emlyn Johnson, flute Erin Lensing, oboe Adrián Sandí, clarinet Michael Tumiel, clarinet Jon Nelson, trumpet Kristen Theriault, harp Eric Huebner, piano Chris Guzman, piano Tom Kolor, percussion Steve Solook, percussion Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano (solo) Julia Cordani, soprano Minxin She, alto Hanna Hurwitz, violin Victor Lowrie, viola Katie Weissman, ‘cello About Bernard Rands Through a catalog of more than a hundred published works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure in contemporary music. His work Canti del Sole, premiered by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta, and the New York Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral suites Le Tambourin, won the 1986 Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. His work Canti d'Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy award in 2000. -

International Media and Communication Statistics 2010

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 1 2 A Sampler of International Media and Communication Statistics 2010 Compiled by Sara Leckner & Ulrika Facht N O R D I C O M Nordic Media Trends 12 A Sampler of International Media and Communication Statistics 2010 COMPILED BY: Sara LECKNER and Ulrika FACHT The Nordic Ministers of Culture have made globalization one of their top priorities, unified in the strategy Creativity – the Nordic Response to Globalization. The aim is to create a more prosperous Nordic Region. This publication is part of this strategy. ISSN 1401-0410 ISBN 978-91-86523-15-2 PUBLISHED BY: NORDICOM University of Gothenburg P O Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Sweden EDITOR NORDIC MEDIA TRENDS: Ulla CARLSSON COVER BY: Roger PALMQVIST Contents Abbrevations 6 Foreword 7 Introduction 9 List of tables & figures 11 Internet in the world 19 ICT 21 The Internet market 22 Computers 32 Internet sites & hosts 33 Languages 36 Internet access 37 Internet use 38 Fixed & mobile telephony 51 Internet by region 63 Africa 65 North & South America 75 Asia & the Pacific 85 Europe 95 Commonwealth of Independent States – CIS 110 Middle East 113 Television in the world 119 The TV market 121 TV access & distribution 127 TV viewing 139 Television by region 143 Africa 145 North & South America 149 Asia & the Pacific 157 Europe 163 Middle East 189 Radio in the world 197 Channels 199 Digital radio 202 Revenues 203 Access 206 Listening 207 Newspapers in the world 211 Top ten titles 213 Language 214 Free dailes 215 Paid-for newspapers 217 Paid-for dailies 218 Revenues & costs 230 Reading 233 References 235 5 Abbreviations General terms . -

Discover-Costa-Rica-At-ULACIT-1.Pdf

-1 -2 -3 In the heart of Central America, Costa Rica is a nation of inspiring people who have built the longest standing democracy in Latin America. This small territory that only encompasses 0.03% of the planet’s surface is home to nearly 5% of the Earth’s biodiversity. Costa Ricans, or Ticos, as they call themselves, have pro- tected over a quarter of their national territory creating national parks, wildlife refuges and biological reserves. Divided into 7 unique provinces: San José, Alajuela, Heredia, Cartago, Guanacaste, Puntarenas and Limón, Costa Rica offers visitors a wide range of experiences able to satisfy varying tastes and interests. Since the abolition of the army in 1948, Costa Rica has re- lied on democratic values and the strength of institutions as the founding pillars for progress and development, re- directing military spending to education and healthcare. Costa Ricans pride themselves in their healthy, peaceful and sustainable lifestyle, which they call “Pura Vida.” These words have become a true identifier for the nation’s vision and a welcoming message to all those ready to discover what Costa Rica has to offer. -4 COSTA RICANS PRIDE THEMSELVES IN THEIR HEALTHY, PEACEFUL AND SUSTAINABLE LIFE- STYLE, WHICH THEY CALL “PURA VIDA.” THESE WORDS HAVE BECOME A TRUE IDEN- TIFIER FOR THE NATION’S VISION AND A WEL- COMING MESSAGE TO ALL THOSE READY TO DISCOVER WHAT COSTA RICA HAS TO OFFER. -5 -6 -7 Happiness 1. comes first Costa Rica topped the Happy Planet Index in 2016, for the third time. This index ranks nations in their efforts to provide sustainable well-being for all. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 Online, Summer 2015

Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Summer 2015: Volume 31, Online Issue p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 In Memoriam Joseph de Pasquale Remembered p. 11 Recalling the AVS Newsletter: English Viola Music Before 1937 In recalling 30 years of this journal, we provide a nod to its predecessor with a reprint of a 1976 article by Thomas Tatton, followed by a brief reflection by the author. Feature Article p. 13 Concerto for Viola Sobre un Canto Bribri by Costa Rican composer Benjamín Gutiérrez Or quídea Guandique provides a detailed look at the first viola concerto of Costa Rica, and how the country’s history influenced its creation. Departments p. 25 In the Studio: Thought Multi-Tasking (or What I Learned about Painting from Playing the Viola) Katrin Meidell discussed the influence of viola technique and pedagogy in unexpected areas of life. p. 29 With Viola in Hand: Experiencing the Viola in Hindustani Classical Music: Gisa Jähnichen, Chinthaka P. Meddegoda, and Ruwin R. Dias experiment with finding a place for the viola in place of the violin in Hindustani classical music. On the Covers: 30 Years of JAVS Covers compiled by Andrew Filmer and David Bynog Editor: Andrew Filmer The Journal of the American Viola Society is Associate Editor: David M. Bynog published in spring and fall and as an online- only issue in summer. The American Viola Departmental Editors: Society is a nonprofit organization of viola At the Grassroots: Christine Rutledge enthusiasts, including students, performers, The Eclectic Violist: David Wallace teachers, scholars, composers, makers, and Fresh Faces: Lembi Veskimets friends, who seek to encourage excellence in In the Studio: Katherine Lewis performance, pedagogy, research, composition, New Music Reviews: Andrew Braddock and lutherie.