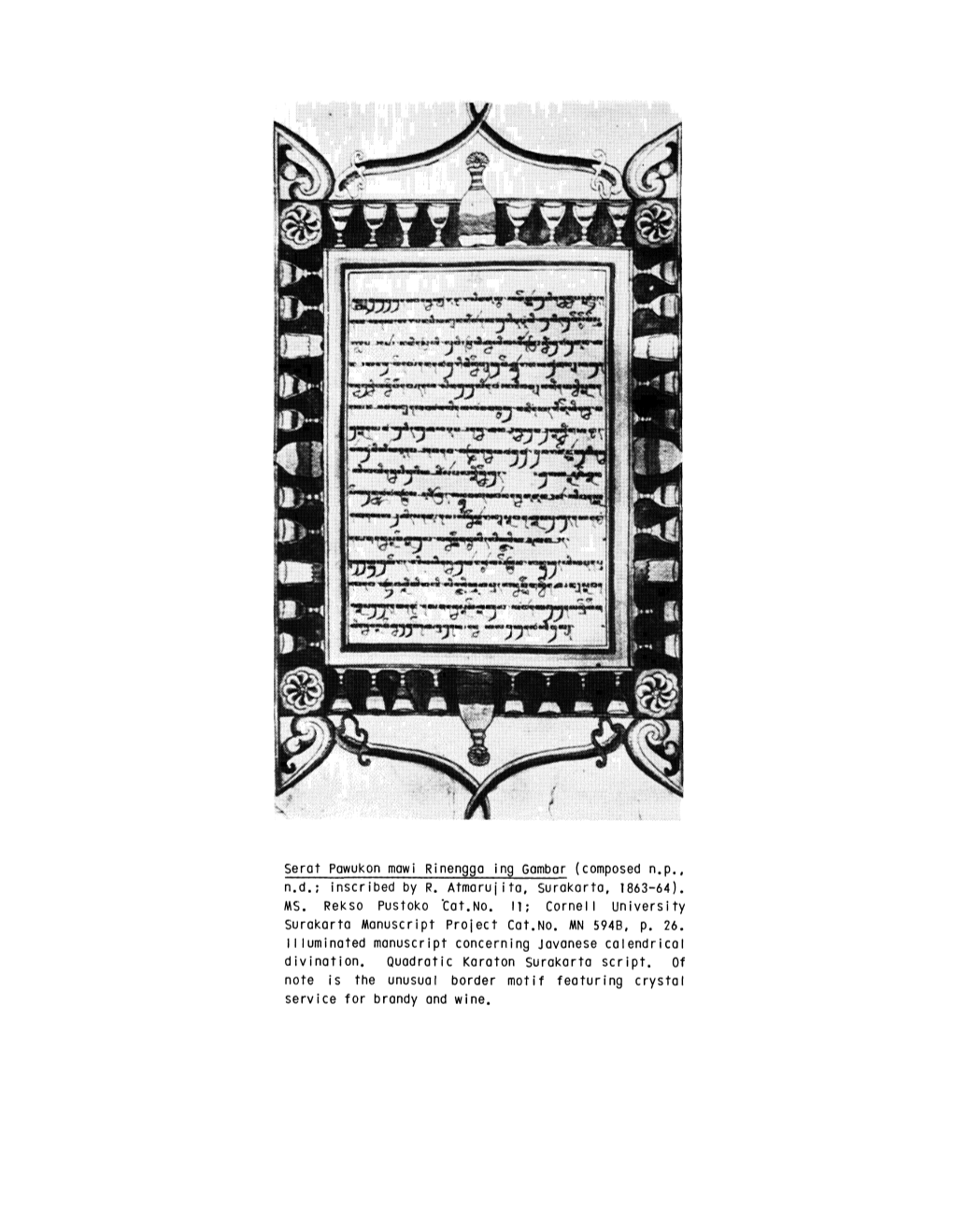

Serαt Pαwukon Mαwi Rinenggo Ing Gαmbαr (Composed N.P.. N.D.; Inscribed by R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Pos. KE QA GE GA Initial ᠬ ᠭ Medial Final

Proposal to encode two Mongolian letters Badral Sanlig [email protected] Jamiyansuren Togoobat [email protected] Munkh-Uchral Enkhtur [email protected] Bolorsoft LLC, Mongolia 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode two additional mongolian letters that are most actively used for writing texts in traditional Mongolian writing system. These letters are at the present partially implemented as variant forms of correspond- ingly QA, GA. The first letter is Mongolian KE, which is known as feminine form of QA and second letter is Mongolian GE, which is known as feminine form of GA. Pos. KE QA GE GA ᠬ ᠭ initial medial final - Table 1: Forms of KE(QA) and GE(GA). In current encoding scheme, only final and medial form of GE are encoded and all other forms of GE, KE (such as initial GE, KE, medial KE) can be illustrated only through open type font algorithms. On top of that, those cur- rently encoded forms of GE are only as variant of GA (medial form of GE is second variant by FVS1, whereas final form of GE is fourth variant by FVS3) implemented. QA, KE, GA, GE are most frequently used characters in Mongol script, as most of the heading words are started by these letters, all nominal forms of verb are built by these letters and all long vowels are illustrated by these letters. To back up our argument, we have done the frequency analysis of Mongol script letters in our lexical database, which contains 41808 non-inflected distinct words (lemma), result of our analysis are shown in Table 2. -

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

2016 Semi Finalists Medals

2016 US Physics Olympiad Semi Finalists Medal Rankings StudentMedal School City State Abbott, Ryan WHopkinsBronze Medal SchoolNew Haven CT Alton, James SLakesideHonorable Mention High SchoolEvans GA ALUMOOTIL, VARKEY TCanyonHonorable Mention Crest AcademySan Diego CA An, Seung HwanGold Medal Taft SchoolWatertown CT Ashary, Rafay AWilliamHonorable Mention P Clements High SchoolSugar Land TX Balaji, ShreyasSilver Medal John Foster Dulles High SchoolSugar Land TX Bao, MikeGold Medal Cambridge Educational InstituteChino Hills CA Beasley, NicholasGold Medal Stuyvesant High SchoolNew York NY BENABOU, JOSHUA N Gold Medal Plandome NY Bhattacharyya, MoinakSilver Medal Lynbrook High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhattaram, Krishnakumar SLynbrookBronze Medal High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhimnathwala, Tarung SBronze Medal Manalapan High SchoolManalapan NJ Boopathy, AkhilanGold Medal Lakeside Upper SchoolSeattle WA Cao, AntonSilver Medal Evergreen Valley High SchoolSan Jose CA Cen, Edward DBellaireHonorable Mention High SchoolBellaire TX Chadraa, Dalai BRedmondHonorable Mention High SchoolRedmond WA Chakrabarti, DarshanBronze Medal Northside College Preparatory HSChicago IL Chan, Clive ALexingtonSilver Medal High SchoolLexington MA Chang, Kevin YBellarmineSilver Medal Coll PrepSan Jose CA Cheerla, NikhilBronze Medal Monta Vista High SchoolSan Jose CA Chen, AlexanderSilver Medal Princeton High SchoolPrinceton NJ Chen, Andrew LMissionSilver Medal San Jose High SchoolFremont CA Chen, Benjamin YArdentSilver Medal Academy for Gifted YouthIrvine CA Chen, Bryan XMontaHonorable -

Java in Jerusalem : New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature and Culture

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 97 | 2019 Varia Java in Jerusalem : New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature and Culture Ronit Ricci and Willem van der Molen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/1004 DOI: 10.4000/archipel.1004 ISSN: 2104-3655 Publisher Association Archipel Printed version Date of publication: 11 June 2019 Number of pages: 13-18 ISBN: 978-2-910513-81-8 ISSN: 0044-8613 Electronic reference Ronit Ricci and Willem van der Molen, “Java in Jerusalem : New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature and Culture”, Archipel [Online], 97 | 2019, Online since 01 June 2019, connection on 15 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/1004 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ archipel.1004 Association Archipel Java in Jerusalem: New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature and Culture Introduction Although the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University on principle welcomes any interesting topic of research, Javanese literature must have been quite out of the ordinary even for this open-minded Institute. Nevertheless, it accepted the proposal that was submitted by Ronit Ricci under the title “New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature.” And so it came about that a group of seven Javanists from around the world are presently carrying out research on Javanese literature in Jerusalem. These are, besides Ronit herself (Jerusalem): Ben Arps (Leiden), Els Bogaerts (Leiden), Tony Day (Graz), Nancy Florida (Ann Arbor), Verena Meyer (New York) and Willem van der Molen (Leiden). During the year, several other researchers will join the group for a couple of weeks to a couple of months, i.e. -

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show As Visualization Media of Javanese Literature

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show as Visualization Media of Javanese Literature Trisno Santoso 1 and Bagus Wahyu Setyawan 2 {[email protected] 1, [email protected] 2} 1Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia Abstract. Puppet shows developing in Javanese culture is definitely various, including wayang kulit, wayang kancil, wayang suket, wayang krucil, wayang klithik, and wayang golek. This study was a developmental research, that developed Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo with using theatre and cinematography approaches. Its aims to develop and create the new form of wayang golek sentolo show, Yogyakarta. The stages included conducting the orientation of wayang golek sentolo show, perfecting the concept, conducting FGD on the development concept, conducting the stage orientation, making wayang puppet protoype, testing the developmental product, and disseminating it in the show. After doing these stages, Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo show gets developed from the original one, in terms of duration that become shorter, language using other languages than Javanese, show techniques that use theatre approach with modern blocking and lighting, voice acting of wayang figure with using dubbing techniques as in animation films, stage developed into portable to ease the movement as needed, as well as the form of wayang created differently from the original in terms of size and materials used. It is expected that the development and new form of wayang golek menak will get more acceptance from the modern community. Keywords: wayang golek menak, development, puppet show, visualization media, Javanese literature, serat menak. 1. INTRODUCTION Discussing about puppet shows in Java, there are two types of puppet shows, namely wayang golek and wayang krucil . -

The Usage of Javanese Literature on the Javanese Shade Shadow Show As the Islamic Proselytizing Medium

Penguatan Komunitas Lokal Menghadapi Era Global ____________________________________________Strengthening Local Communities Facing the Global Era THE USAGE OF JAVANESE LITERATURE ON THE JAVANESE SHADE SHADOW SHOW AS THE ISLAMIC PROSELYTIZING MEDIUM By: Ageng Soeharno, S.S., M.Pd. ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to describe the usage of javanese literature on the javanese shade shadow showas the islamic proselytizing medium. The conclution show that is the trailer of the song which tell us about the history of the Islamic Javanese Guardian. It can be concluded here that the song is including to the New Javanese Literature, because the touch of the Islam is felt very much here.Eventually, the writer hopes that this writing will be greatly useful to the reader. Keywords: usage, Javanese literature Introduction Indonesia is a big country which has so many cultures. One of them is Javanese Shade Shadow Show. This is the show, which combine several characters in it. On performing the show, narrator and puppeteer of the traditional shadow play usually uses old Javanese, or Kawi Language as the conducting language, or even the new one. They practiced the Javanese literature. The old Javanese Literature, consciously or not, was a mirror of the Javanese culture condition at the time (Karsono, 2006:25). The literature is not only used by the shades shadow puppet show player to attract their ability on narrating or just expressing the character of the puppets but also the medium to proselytize the Islamic religion. According to the statement above, the problem turn up now is: how is the role of Islam in influencing the Javanese Literature that is used by the puppeters on their show? Based on the problem stated above, of course, we have to observe intently to get the objective we use to answer the problem we have written before. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

Sacral Chakra

Tour of the Chakras Series: Sacral Chakra M a y 20 1 6 © 20 1 2 by Angelique M. Bouffiou V o lu me 1, Issue 3 MysticsAlchemy9. co m Mystic, Writer, Teacher Svadhishthana, the 2nd Chakra The sacral chakra is the second chakra dreams or plans can be made manifest counting from root to crown. This energy into reality. Therefore, it is ultimately center runs through the reproductive and sex important to keep this chakra in balance organs. The Sanskrit name is Svadhishthana. and harmonized. The element of this chakra is water, which is represented in the image, on the left, by the The root and sacral chakras are silver crescent moon. On each petal is a connected. Well, actually all the chakras are connected. However, an imbalance in syllable. The mantra Vam is written in the center. Chanting the syllables "Ba, Bha, Ma, the root can offset the sacral easily. You Ya, Ra La" or the mantra "Vam", can assist in will also learn how to recognize imbalance Svadhisthana chakra unfolding and balancing this chakra. and how to harmonize these energies for 2nd chakra your empowerment. The energy that runs through this chakra is If you are having trouble manifesting the sexual creative energy, not the sexual OR those dreams or plans, it may be that you creative energy. Sexual energy and creative are blocked by shame, doubt, guilt, fear or energy are one in the same. Whether you are a defunct story. Worry not! We will look Contents creating babies or a business, the focus is into some ways to clear these. -

Javanese Cosmology: Symbolic Transformation of Names in Javanese Novels

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 7 Original Research Javanese cosmology: Symbolic transformation of names in Javanese novels Authors: In the past, no research has been found on onomastics from a mystical perspective in literature. 1,2 Onok Y. Pamungkas This study investigated onomastics in the tetralogy of novels by Ki Padmasusastra (after this Sahid T. Widodo3 Suyitno Suyitno3 referred to as TNKP). The main point of view is the meaning of Javanese cosmology. Qualitative Suwardi Endraswara4 methods are used as research guidelines. The primary data are four Javanese novels. Hermeneutic techniques and content analysis are applied to analytical strategies. The results Affiliations: showed that the onomastics in TNKP are symbols of Javanese cosmology. This element of 1Study Program of Indonesian Javanese cosmology has transformed onomastics through three things: the novel title, figure’s Language Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and name and location name. The symbolisation of the onomastic is implicit because it is wrapped Education, Universitas Sebelas in the aesthetics of the literary language. The name structure of each onomastic subsection has Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia no clear meaning because the name element is intended for the sense of ‘the other’. Names have an explicit function, namely as hypertextual fragments of symbols that transcend the 2 Study Program of Indonesian narrative text structure. An important implication of this investigation is that onomastics can Language Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and promote the transdisciplinary aspects of religion in international theology in the study of Education, Universitas Ma’arif narrative texts. The cosmological transformation of Java can be reflected in various parts of Nahdlatul Ulama, Kebumen, culture, including in novels. -

M. Van Bruinessen Najmuddin Al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin Al-Akbar; Traces of Kubrawiyya Influence in Early Indonesian Islam

M. van Bruinessen Najmuddin al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin al-Akbar; Traces of Kubrawiyya influence in early Indonesian islam In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 150 (1994), no: 2, Leiden, 305-329 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 02:48:13PM via free access MARTIN VAN BRUINESSEN Najmuddin al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin al-Akbar Traces of Kubrawiyya Influence in Early Indonesian Islam The Javanese Sajarah Banten rante-rante (hereafter abbreviated as SBR) and its Malay translation Hikayat Hasanuddin, compiled in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century but incorporating much older material, consist of a number of disparate narratives, one of which tells of the alleged studies of Sunan Gunung Jati in Mecca.1 A very similar, though less detailed, account is contained in the Brandes-Rinkes recension of the Babad Cirebon. Sunan Gunung Jati, venerated as one of the nine saints of Java, is a historical person, who lived in the first half of the 16th century and founded the Muslim kingdoms of Banten and Cirebon. Present tradition gives his proper name as Syarif Hidayatullah; the babad literature names him variously as Sa'ad Kamil, Muhammad Nuruddin, Nurullah Ibrahim, and Maulana Shaikh Madhkur, and has him born either in Egypt or in Pasai, in north Sumatra. It appears that a number of different historical and legendary persons have merged into the Sunan Gunung Jati of the babad. Sunan Gunung Jati and the Kubrawiyya The historical Sunan Gunung Jati may or may not have actually visited Mecca and Medina.