3 Relativity Beta Decay.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay

REPORT TO THE NUCLEAR SCIENCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay NOVEMBER 18, 2015 NLDBD Report November 18, 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In March 2015, DOE and NSF charged NSAC Subcommittee on neutrinoless double beta decay (NLDBD) to provide additional guidance related to the development of next generation experimentation for this field. The new charge (Appendix A) requests a status report on the existing efforts in this subfield, along with an assessment of the necessary R&D required for each candidate technology before a future downselect. The Subcommittee membership was augmented to replace several members who were not able to continue in this phase (the present Subcommittee membership is attached as Appendix B). The Subcommittee solicited additional written input from the present worldwide collaborative efforts on double beta decay projects in order to collect the information necessary to address the new charge. An open meeting was held where these collaborations were invited to present material related to their current projects, conceptual designs for next generation experiments, and the critical R&D required before a potential down-select. We also heard presentations related to nuclear theory and the impact of future cosmological data on the subject of NLDBD. The Subcommittee presented its principal findings and comments in response to the March 2015 charge at the NSAC meeting in October 2015. The March 2015 charge requested the Subcommittee to: Assess the status of ongoing R&D for NLDBD candidate technology demonstrations for a possible future ton-scale NLDBD experiment. For each candidate technology demonstration, identify the major remaining R&D tasks needed ONLY to demonstrate downselect criteria, including the sensitivity goals, outlined in the NSAC report of May 2014. -

RIB Production by Photofission in the Framework of the ALTO Project

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com NIM B Beam Interactions with Materials & Atoms Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B 266 (2008) 4092–4096 www.elsevier.com/locate/nimb RIB production by photofission in the framework of the ALTO project: First experimental measurements and Monte-Carlo simulations M. Cheikh Mhamed *, S. Essabaa, C. Lau, M. Lebois, B. Roussie`re, M. Ducourtieux, S. Franchoo, D. Guillemaud Mueller, F. Ibrahim, J.F. LeDu, J. Lesrel, A.C. Mueller, M. Raynaud, A. Said, D. Verney, S. Wurth Institut de Physique Nucle´aire, IN2P3-CNRS/Universite´ Paris-Sud, F-91406 Orsay Cedex, France Available online 11 June 2008 Abstract The ALTO facility (Acce´le´rateur Line´aire aupre`s du Tandem d’Orsay) has been built and is now under commissioning. The facility is intended for the production of low energy neutron-rich ion-beams by ISOL technique. This will open new perspectives in the study of nuclei very far from the valley of stability. Neutron-rich nuclei are produced by photofission in a thick uranium carbide target (UCx) using a 10 lA, 50 MeV electron beam. The target is the same as that already had been used on the previous deuteron based fission ISOL setup (PARRNE [F. Clapier et al., Phys. Rev. ST-AB (1998) 013501.]). The intended nominal fission rate is about 1011 fissions/s. We have studied the adequacy of a thick carbide uranium target to produce neutron-rich nuclei by photofission by means of Monte-Carlo simulations. We present the production rates in the target and after extraction and mass separation steps. -

Chapter 3 the Fundamentals of Nuclear Physics Outline Natural

Outline Chapter 3 The Fundamentals of Nuclear • Terms: activity, half life, average life • Nuclear disintegration schemes Physics • Parent-daughter relationships Radiation Dosimetry I • Activation of isotopes Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The physics of radiology, 4th ed. http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Natural radioactivity Activity • Activity – number of disintegrations per unit time; • Particles inside a nucleus are in constant motion; directly proportional to the number of atoms can escape if acquire enough energy present • Most lighter atoms with Z<82 (lead) have at least N Average one stable isotope t / ta A N N0e lifetime • All atoms with Z > 82 are radioactive and t disintegrate until a stable isotope is formed ta= 1.44 th • Artificial radioactivity: nucleus can be made A N e0.693t / th A 2t / th unstable upon bombardment with neutrons, high 0 0 Half-life energy protons, etc. • Units: Bq = 1/s, Ci=3.7x 1010 Bq Activity Activity Emitted radiation 1 Example 1 Example 1A • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. If the What percent of the dose is delivered in the first initial dose rate is 10cGy/h, what is the total dose day? N N delivered? t /th t 2 or e Dtotal D0tavg N0 N0 A. 0.5 A. 9 0.693t 0.693t B. 2 t /th 1/17 t 2 2 0.96 B. 29 D D e th dt D h e th C. 4 total 0 0 0.693 0.693t /th 0.6931/17 C. -

Radioactive Decay

North Berwick High School Department of Physics Higher Physics Unit 2 Particles and Waves Section 3 Fission and Fusion Section 3 Fission and Fusion Note Making Make a dictionary with the meanings of any new words. Einstein and nuclear energy 1. Write down Einstein’s famous equation along with units. 2. Explain the importance of this equation and its relevance to nuclear power. A basic model of the atom 1. Copy the components of the atom diagram and state the meanings of A and Z. 2. Copy the table on page 5 and state the difference between elements and isotopes. Radioactive decay 1. Explain what is meant by radioactive decay and copy the summary table for the three types of nuclear radiation. 2. Describe an alpha particle, including the reason for its short range and copy the panel showing Plutonium decay. 3. Describe a beta particle, including its range and copy the panel showing Tritium decay. 4. Describe a gamma ray, including its range. Fission: spontaneous decay and nuclear bombardment 1. Describe the differences between the two methods of decay and copy the equation on page 10. Nuclear fission and E = mc2 1. Explain what is meant by the terms ‘mass difference’ and ‘chain reaction’. 2. Copy the example showing the energy released during a fission reaction. 3. Briefly describe controlled fission in a nuclear reactor. Nuclear fusion: energy of the future? 1. Explain why nuclear fusion might be a preferred source of energy in the future. 2. Describe some of the difficulties associated with maintaining a controlled fusion reaction. -

![Arxiv:1901.01410V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 Mental Information Is Available, and One Has to Rely Strongly on Theoretical Predictions for Nuclear Properties](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8159/arxiv-1901-01410v3-astro-ph-he-1-feb-2021-mental-information-is-available-and-one-has-to-rely-strongly-on-theoretical-predictions-for-nuclear-properties-508159.webp)

Arxiv:1901.01410V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 Mental Information Is Available, and One Has to Rely Strongly on Theoretical Predictions for Nuclear Properties

Origin of the heaviest elements: The rapid neutron-capture process John J. Cowan∗ HLD Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, 440 W. Brooks St., Norman, OK 73019, USA Christopher Snedeny Department of Astronomy, University of Texas, 2515 Speedway, Austin, TX 78712-1205, USA James E. Lawlerz Physics Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1150 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706-1390, USA Ani Aprahamianx and Michael Wiescher{ Department of Physics and Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics, University of Notre Dame, 225 Nieuwland Science Hall, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA Karlheinz Langanke∗∗ GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany and Institut f¨urKernphysik (Theoriezentrum), Fachbereich Physik, Technische Universit¨atDarmstadt, Schlossgartenstraße 2, 64298 Darmstadt, Germany Gabriel Mart´ınez-Pinedoyy GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany; Institut f¨urKernphysik (Theoriezentrum), Fachbereich Physik, Technische Universit¨atDarmstadt, Schlossgartenstraße 2, 64298 Darmstadt, Germany; and Helmholtz Forschungsakademie Hessen f¨urFAIR, GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany Friedrich-Karl Thielemannzz Department of Physics, University of Basel, Klingelbergstrasse 82, 4056 Basel, Switzerland and GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany (Dated: February 2, 2021) The production of about half of the heavy elements found in nature is assigned to a spe- cific astrophysical nucleosynthesis process: the rapid neutron capture process (r-process). Although this idea has been postulated more than six decades ago, the full understand- ing faces two types of uncertainties/open questions: (a) The nucleosynthesis path in the nuclear chart runs close to the neutron-drip line, where presently only limited experi- arXiv:1901.01410v3 [astro-ph.HE] 1 Feb 2021 mental information is available, and one has to rely strongly on theoretical predictions for nuclear properties. -

Two-Proton Radioactivity 2

Two-proton radioactivity Bertram Blank ‡ and Marek P loszajczak † ‡ Centre d’Etudes Nucl´eaires de Bordeaux-Gradignan - Universit´eBordeaux I - CNRS/IN2P3, Chemin du Solarium, B.P. 120, 33175 Gradignan Cedex, France † Grand Acc´el´erateur National d’Ions Lourds (GANIL), CEA/DSM-CNRS/IN2P3, BP 55027, 14076 Caen Cedex 05, France Abstract. In the first part of this review, experimental results which lead to the discovery of two-proton radioactivity are examined. Beyond two-proton emission from nuclear ground states, we also discuss experimental studies of two-proton emission from excited states populated either by nuclear β decay or by inelastic reactions. In the second part, we review the modern theory of two-proton radioactivity. An outlook to future experimental studies and theoretical developments will conclude this review. PACS numbers: 23.50.+z, 21.10.Tg, 21.60.-n, 24.10.-i Submitted to: Rep. Prog. Phys. Version: 17 December 2013 arXiv:0709.3797v2 [nucl-ex] 23 Apr 2008 Two-proton radioactivity 2 1. Introduction Atomic nuclei are made of two distinct particles, the protons and the neutrons. These nucleons constitute more than 99.95% of the mass of an atom. In order to form a stable atomic nucleus, a subtle equilibrium between the number of protons and neutrons has to be respected. This condition is fulfilled for 259 different combinations of protons and neutrons. These nuclei can be found on Earth. In addition, 26 nuclei form a quasi stable configuration, i.e. they decay with a half-life comparable or longer than the age of the Earth and are therefore still present on Earth. -

Heavy Element Nucleosynthesis

Heavy Element Nucleosynthesis A summary of the nucleosynthesis of light elements is as follows 4He Hydrogen burning 3He Incomplete PP chain (H burning) 2H, Li, Be, B Non-thermal processes (spallation) 14N, 13C, 15N, 17O CNO processing 12C, 16O Helium burning 18O, 22Ne α captures on 14N (He burning) 20Ne, Na, Mg, Al, 28Si Partly from carbon burning Mg, Al, Si, P, S Partly from oxygen burning Ar, Ca, Ti, Cr, Fe, Ni Partly from silicon burning Isotopes heavier than iron (as well as some intermediate weight iso- topes) are made through neutron captures. Recall that the prob- ability for a non-resonant reaction contained two components: an exponential reflective of the quantum tunneling needed to overcome electrostatic repulsion, and an inverse energy dependence arising from the de Broglie wavelength of the particles. For neutron cap- tures, there is no electrostatic repulsion, and, in complex nuclei, virtually all particle encounters involve resonances. As a result, neutron capture cross-sections are large, and are very nearly inde- pendent of energy. To appreciate how heavy elements can be built up, we must first consider the lifetime of an isotope against neutron capture. If the cross-section for neutron capture is independent of energy, then the lifetime of the species will be ( )1=2 1 1 1 µn τn = ≈ = Nnhσvi NnhσivT Nnhσi 2kT For a typical neutron cross-section of hσi ∼ 10−25 cm2 and a tem- 8 9 perature of 5 × 10 K, τn ∼ 10 =Nn years. Next consider the stability of a neutron rich isotope. If the ratio of of neutrons to protons in an atomic nucleus becomes too large, the nucleus becomes unstable to beta-decay, and a neutron is changed into a proton via − (Z; A+1) −! (Z+1;A+1) + e +ν ¯e (27:1) The timescale for this decay is typically on the order of hours, or ∼ 10−3 years (with a factor of ∼ 103 scatter). -

2.3 Neutrino-Less Double Electron Capture - Potential Tool to Determine the Majorana Neutrino Mass by Z.Sujkowski, S Wycech

DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SPECTROSCOPY AND TECHNIQUE 39 The above conservatively large systematic hypothesis. TIle quoted uncertainties will be soon uncertainty reflects the fact that we did not finish reduced as our analysis progresses. evaluating the corrections fully in the current analysis We are simultaneously recording a large set of at the time of this writing, a situation that will soon radiative decay events for the processes t e'v y change. This result is to be compared with 1he and pi-+eN v y. The former will be used to extract previous most accurate measurement of McFarlane the ratio FA/Fv of the axial and vector form factors, a et al. (Phys. Rev. D 1984): quantity of great and longstanding interest to low BR = (1.026 ± 0.039)'1 I 0 energy effective QCD theory. Both processes are as well as with the Standard Model (SM) furthermore very sensitive to non- (V-A) admixtures in prediction (Particle Data Group - PDG 2000): the electroweak lagLangian, and thus can reveal BR = (I 038 - 1.041 )*1 0-s (90%C.L.) information on physics beyond the SM. We are currently analyzing these data and expect results soon. (1.005 - 1.008)* 1W') - excl. rad. corr. Tale 1 We see that even working result strongly confirms Current P1IBETA event sxpelilnentstatistics, compared with the the validity of the radiative corrections. Another world data set. interesting comparison is with the prediction based on Decay PIBETA World data set the most accurate evaluation of the CKM matrix n >60k 1.77k element V d based on the CVC hypothesis and ihce >60 1.77_ _ _ results -

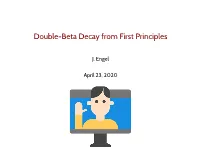

Double-Beta Decay from First Principles

Double-Beta Decay from First Principles J. Engel April 23, 2020 Goal is set of matrix elements with real error bars by May, 2021 DBD Topical Theory Collaboration Lattice QCD Data Chiral EFT Similarity Renormalization Group Ab-Initio Many-Body Methods Harmonic No-Core Quantum Oscillator Basis Shell Model Monte Carlo Effective Theory Light Nuclei (benchmarking) DFT-Inspired Coupled Multi-reference In-Medium SRG Clusters In-Medium SRG for Shell Model Heavy Nuclei DFT Statistical Model Averaging (for EDMs) Shell Model Goal is set of matrix elements with real error bars by May, 2021 DBD Topical Theory Collaboration Haxton HOBET Walker-Loud McIlvain LQCD Brantley Monge- Johnson Camacho Ramsey- SM Musolf Horoi Engel EFT SM Cirigliano Nicholson Mereghetti "DFT" EFT LQCD QMC Carlson Jiao Quaglioni Vary SRG NC-SM Yao Papenbrock LQCD = Latice QCD Hagen EFT = Effective Field Theory Bogner QMC = Quantum Monte Carlo Morris Hergert DFT = Densty Functional Theory Sun Nazarewicz Novario SRG = Similarity Renormilazation Group More IM-SRG IM-SRG = In-Medium SRG Coupled Clusters DFT HOBET = Harmonic-Oscillator-Based Statistics Effective Theory NC-SM = No-Core Shell Model SM = Shell Model DBD Topical Theory Collaboration Haxton HOBET Walker-Loud McIlvain LQCD Brantley Monge- Johnson Camacho Ramsey- SM Musolf Horoi Engel EFT SM Cirigliano Nicholson Mereghetti "DFT" EFT LQCD QMC Carlson Jiao Quaglioni Vary Goal is set of matrixSRG elementsNC-SM with Yao real error bars by May, 2021 Papenbrock LQCD = Latice QCD Hagen EFT = Effective Field Theory Bogner QMC = Quantum Monte Carlo Morris Hergert DFT = Densty Functional Theory Sun Nazarewicz Novario SRG = Similarity Renormilazation Group More IM-SRG IM-SRG = In-Medium SRG Coupled Clusters DFT HOBET = Harmonic-Oscillator-Based Statistics Effective Theory NC-SM = No-Core Shell Model SM = Shell Model Part 0 0νββ Decay and neutrinos are their own antiparticles.. -

Problem Set 3 Solutions

22.01 Fall 2016, Problem Set 3 Solutions October 9, 2016 Complete all the assigned problems, and do make sure to show your intermediate work. 1 Activity and Half Lives 1. Given the half lives and modern-day abundances of the three natural isotopes of uranium, calculate the isotopic fractions of uranium when the Earth first formed 4.5 billion years ago. Today, uranium consists of 0.72% 235U, 99.2745% 238U, and 0.0055% 234U. However, it is clear that the half life of 234U (245,500 years) is so short compared to the lifetime of the Earth (4,500,000,000 years) that it would have all decayed away had there been some during the birth of the Earth. Therefore, we look a little closer, and find that 234U is an indirect decay product of 238U, by tracing it back from its parent nuclides on the KAERI table: α β− β− 238U −! 234T h −! 234P a −! 234U (1) Therefore we won’t consider there being any more 234U than would normally be in equi librium with the 238U around at the time. We set up the two remaining equations as follows: −t t ;235 −t t ;238 = 1=2 = 1=2 N235 = N0235 e N238 = N0238 e (2) Using the current isotopic abundances from above as N235 and N238 , the half lives from n 9 t 1 1 the KAERI Table of Nuclides t =2;235 = 703800000 y; t =2;238 = 4:468 · 10 y , and the lifetime of the earth in years (keeping everything in the same units), we arrive at the following expressions for N0235 and N0238 : N235 0:0072 N238 0:992745 N0235 =−t = 9 = 4:307N0238 =−t = 9 = 2:718 (3) =t1 ;235 −4:5·10 =7:038·108 =t1 ;238 −4:5·10 =4:468·109 e =2 e e =2 e Finally, taking the ratios of these two relative abundances gives us absolute abundances: 4:307 2:718 f235 = = 0:613 f238 = = 0:387 (4) 4:307 + 2:718 4:307 + 2:718 235U was 61.3% abundant, and 238U was 38.7% abundant. -

Abundance and Radioactivity of Unstable Isotopes

5 RADIONUCLIDE DECAY AND PRODUCTION This section contains a brief review of relevant facts about radioactivity, i.e. the phenomenon of nuclear decay, and about nuclear reactions, the production of nuclides. For full details the reader is referred to textbooks on nuclear physics and radiochemistry, and on the application of radioactivity in the earth sciences (cited in the list of references). 5.1 NUCLEAR INSTABILITY If a nucleus contains too great an excess of neutrons or protons, it will sooner or later disintegrate to form a stable nucleus. The different modes of radioactive decay will be discussed briefly. The various changes that can take place in the nucleus are shown in Fig.5.1 In transforming into a more stable nucleus, the unstable nucleus looses potential energy, part of its binding energy. This energy Q is emitted as kinetic energy and is shared by the particles formed according to the laws of conservation of energy and momentum (see Sect.5.3). The energy released during nuclear decay can be calculated from the mass budget of the decay reaction, using the equivalence of mass and energy, discussed in Sect.2.4. The atomic mass determinations have been made very accurately and precisely by mass spectrometric measurement: 2 E = [Mparent Mdaughter] P mc (5.1) with 1 amu V 931.5 MeV (5.2) Disintegration of a parent nucleus produces a daughter nucleus which generally is in an excited state. After an extremely short time the daughter nucleus looses the excitation energy through the emittance of one or more (gamma) rays, electromagnetic radiation with a very short wavelength, similar to the emission of light (also electromagnetic radiation , but with a longer wavelength) by atoms which have been brought into an excited state. -

Two-Proton Decay Energy and Width of 19Mg(G.S.)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Physics Papers Department of Physics 7-30-2007 Two-Proton Decay Energy and Width of 19Mg(g.s.) H. Terry Fortune University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Rubby Sherr Princeton University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/physics_papers Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Fortune, H. T., & Sherr, R. (2007). Two-Proton Decay Energy and Width of 19Mg(g.s.). Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/physics_papers/171 Suggested Citation: H.T. Fortune and R. Sherr. (2007). Two-proton decay energy and width of 19Mg(g.s.). Physical Review C 76, 014313. © 2007 The American Physical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.76.014313 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/physics_papers/171 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Two-Proton Decay Energy and Width of 19Mg(g.s.) Abstract We use a weak-coupling procedure and results of a shell-model calculation to compute the two-proton separation energy of 19Mg. Our result is at the upper end of the previous range, but 19Mg is still bound for single proton decay to 18Na. We also calculate the 2p decay width. Disciplines Physical Sciences and Mathematics | Physics Comments Suggested Citation: H.T. Fortune and R. Sherr. (2007). Two-proton decay energy and width of 19Mg(g.s.). Physical Review C 76, 014313. © 2007 The American Physical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.76.014313 This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/physics_papers/171 PHYSICAL REVIEW C 76, 014313 (2007) Two-proton decay energy and width of 19Mg(g.s.) H.