Heavy Element Nucleosynthesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hetc-3Step Calculations of Proton Induced Nuclide Production Cross Sections at Incident Energies Between 20 Mev and 5 Gev

JAERI-Research 96-040 JAERI-Research—96-040 JP9609132 JP9609132 HETC-3STEP CALCULATIONS OF PROTON INDUCED NUCLIDE PRODUCTION CROSS SECTIONS AT INCIDENT ENERGIES BETWEEN 20 MEV AND 5 GEV August 1996 Hiroshi TAKADA, Nobuaki YOSHIZAWA* and Kenji ISHIBASHI* Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute 2 G 1 0 1 (T319-11 l This report is issued irregularly. Inquiries about availability of the reports should be addressed to Research Information Division, Department of Intellectual Resources, Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute, Tokai-mura, Naka-gun, Ibaraki-ken, 319-11, Japan. © Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute, 1996 JAERI-Research 96-040 HETC-3STEP Calculations of Proton Induced Nuclide Production Cross Sections at Incident Energies between 20 MeV and 5 GeV Hiroshi TAKADA, Nobuaki YOSHIZAWA* and Kenji ISHIBASHP* Department of Reactor Engineering Tokai Research Establishment Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute Tokai-mura, Naka-gun, Ibaraki-ken (Received July 1, 1996) For the OECD/NEA code intercomparison, nuclide production cross sections of l60, 27A1, nalFe, 59Co, natZr and 197Au for the proton incidence with energies of 20 MeV to 5 GeV are calculated with the HETC-3STEP code based on the intranuclear cascade evaporation model including the preequilibrium and high energy fission processes. In the code, the level density parameter derived by Ignatyuk, the atomic mass table of Audi and Wapstra and the mass formula derived by Tachibana et al. are newly employed in the evaporation calculation part. The calculated results are compared with the experimental ones. It is confirmed that HETC-3STEP reproduces the production of the nuclides having the mass number close to that of the target nucleus with an accuracy of a factor of two to three at incident proton energies above 100 MeV for natZr and 197Au. -

Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay

REPORT TO THE NUCLEAR SCIENCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay NOVEMBER 18, 2015 NLDBD Report November 18, 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In March 2015, DOE and NSF charged NSAC Subcommittee on neutrinoless double beta decay (NLDBD) to provide additional guidance related to the development of next generation experimentation for this field. The new charge (Appendix A) requests a status report on the existing efforts in this subfield, along with an assessment of the necessary R&D required for each candidate technology before a future downselect. The Subcommittee membership was augmented to replace several members who were not able to continue in this phase (the present Subcommittee membership is attached as Appendix B). The Subcommittee solicited additional written input from the present worldwide collaborative efforts on double beta decay projects in order to collect the information necessary to address the new charge. An open meeting was held where these collaborations were invited to present material related to their current projects, conceptual designs for next generation experiments, and the critical R&D required before a potential down-select. We also heard presentations related to nuclear theory and the impact of future cosmological data on the subject of NLDBD. The Subcommittee presented its principal findings and comments in response to the March 2015 charge at the NSAC meeting in October 2015. The March 2015 charge requested the Subcommittee to: Assess the status of ongoing R&D for NLDBD candidate technology demonstrations for a possible future ton-scale NLDBD experiment. For each candidate technology demonstration, identify the major remaining R&D tasks needed ONLY to demonstrate downselect criteria, including the sensitivity goals, outlined in the NSAC report of May 2014. -

RIB Production by Photofission in the Framework of the ALTO Project

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com NIM B Beam Interactions with Materials & Atoms Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B 266 (2008) 4092–4096 www.elsevier.com/locate/nimb RIB production by photofission in the framework of the ALTO project: First experimental measurements and Monte-Carlo simulations M. Cheikh Mhamed *, S. Essabaa, C. Lau, M. Lebois, B. Roussie`re, M. Ducourtieux, S. Franchoo, D. Guillemaud Mueller, F. Ibrahim, J.F. LeDu, J. Lesrel, A.C. Mueller, M. Raynaud, A. Said, D. Verney, S. Wurth Institut de Physique Nucle´aire, IN2P3-CNRS/Universite´ Paris-Sud, F-91406 Orsay Cedex, France Available online 11 June 2008 Abstract The ALTO facility (Acce´le´rateur Line´aire aupre`s du Tandem d’Orsay) has been built and is now under commissioning. The facility is intended for the production of low energy neutron-rich ion-beams by ISOL technique. This will open new perspectives in the study of nuclei very far from the valley of stability. Neutron-rich nuclei are produced by photofission in a thick uranium carbide target (UCx) using a 10 lA, 50 MeV electron beam. The target is the same as that already had been used on the previous deuteron based fission ISOL setup (PARRNE [F. Clapier et al., Phys. Rev. ST-AB (1998) 013501.]). The intended nominal fission rate is about 1011 fissions/s. We have studied the adequacy of a thick carbide uranium target to produce neutron-rich nuclei by photofission by means of Monte-Carlo simulations. We present the production rates in the target and after extraction and mass separation steps. -

An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium

SYNOPSIS An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium The discovery that copernicium can decay into a new isotope of darmstadtium and the observation of a previously unseen excited state of copernicium provide clues to the location of the “island of stability.” By Katherine Wright holy grail of nuclear physics is to understand the stability uncover its position. of the periodic table’s heaviest elements. The problem Ais, these elements only exist in the lab and are hard to The team made their discoveries while studying the decay of make. In an experiment at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy isotopes of flerovium, which they created by hitting a plutonium Ion Research in Germany, researchers have now observed a target with calcium ions. In their experiments, flerovium-288 previously unseen isotope of the heavy element darmstadtium (Z = 114, N = 174) decayed first into copernicium-284 and measured the decay of an excited state of an isotope of (Z = 112, N = 172) and then into darmstadtium-280 (Z = 110, another heavy element, copernicium [1]. The results could N = 170), a previously unseen isotope. They also measured an provide “anchor points” for theories that predict the stability of excited state of copernicium-282, another isotope of these heavy elements, says Anton Såmark-Roth, of Lund copernicium. Copernicium-282 is interesting because it University in Sweden, who helped conduct the experiments. contains an even number of protons and neutrons, and researchers had not previously measured an excited state of a A nuclide’s stability depends on how many protons (Z) and superheavy even-even nucleus, Såmark-Roth says. -

The R-Process Nucleosynthesis and Related Challenges

EPJ Web of Conferences 165, 01025 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201716501025 NPA8 2017 The r-process nucleosynthesis and related challenges Stephane Goriely1,, Andreas Bauswein2, Hans-Thomas Janka3, Oliver Just4, and Else Pllumbi3 1Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Université Libre de Bruxelles, CP 226, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Heidelberger Institut fr¨ Theoretische Studien, Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg 35, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany 3Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Postfach 1317, 85741 Garching, Germany 4Astrophysical Big Bang Laboratory, RIKEN, 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Saitama, 351-0198, Japan Abstract. The rapid neutron-capture process, or r-process, is known to be of fundamental importance for explaining the origin of approximately half of the A > 60 stable nuclei observed in nature. Recently, special attention has been paid to neutron star (NS) mergers following the confirmation by hydrodynamic simulations that a non-negligible amount of matter can be ejected and by nucleosynthesis calculations combined with the predicted astrophysical event rate that such a site can account for the majority of r-material in our Galaxy. We show here that the combined contribution of both the dynamical (prompt) ejecta expelled during binary NS or NS-black hole (BH) mergers and the neutrino and viscously driven outflows generated during the post-merger remnant evolution of relic BH-torus systems can lead to the production of r-process elements from mass number A > 90 up to actinides. The corresponding abundance distribution is found to reproduce the∼ solar distribution extremely well. It can also account for the elemental distributions observed in low-metallicity stars. However, major uncertainties still affect our under- standing of the composition of the ejected matter. -

Chapter 3 the Fundamentals of Nuclear Physics Outline Natural

Outline Chapter 3 The Fundamentals of Nuclear • Terms: activity, half life, average life • Nuclear disintegration schemes Physics • Parent-daughter relationships Radiation Dosimetry I • Activation of isotopes Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The physics of radiology, 4th ed. http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Natural radioactivity Activity • Activity – number of disintegrations per unit time; • Particles inside a nucleus are in constant motion; directly proportional to the number of atoms can escape if acquire enough energy present • Most lighter atoms with Z<82 (lead) have at least N Average one stable isotope t / ta A N N0e lifetime • All atoms with Z > 82 are radioactive and t disintegrate until a stable isotope is formed ta= 1.44 th • Artificial radioactivity: nucleus can be made A N e0.693t / th A 2t / th unstable upon bombardment with neutrons, high 0 0 Half-life energy protons, etc. • Units: Bq = 1/s, Ci=3.7x 1010 Bq Activity Activity Emitted radiation 1 Example 1 Example 1A • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. If the What percent of the dose is delivered in the first initial dose rate is 10cGy/h, what is the total dose day? N N delivered? t /th t 2 or e Dtotal D0tavg N0 N0 A. 0.5 A. 9 0.693t 0.693t B. 2 t /th 1/17 t 2 2 0.96 B. 29 D D e th dt D h e th C. 4 total 0 0 0.693 0.693t /th 0.6931/17 C. -

Compilation and Evaluation of Fission Yield Nuclear Data Iaea, Vienna, 2000 Iaea-Tecdoc-1168 Issn 1011–4289

IAEA-TECDOC-1168 Compilation and evaluation of fission yield nuclear data Final report of a co-ordinated research project 1991–1996 December 2000 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Nuclear Data Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria COMPILATION AND EVALUATION OF FISSION YIELD NUCLEAR DATA IAEA, VIENNA, 2000 IAEA-TECDOC-1168 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2000 Printed by the IAEA in Austria December 2000 FOREWORD Fission product yields are required at several stages of the nuclear fuel cycle and are therefore included in all large international data files for reactor calculations and related applications. Such files are maintained and disseminated by the Nuclear Data Section of the IAEA as a member of an international data centres network. Users of these data are from the fields of reactor design and operation, waste management and nuclear materials safeguards, all of which are essential parts of the IAEA programme. In the 1980s, the number of measured fission yields increased so drastically that the manpower available for evaluating them to meet specific user needs was insufficient. To cope with this task, it was concluded in several meetings on fission product nuclear data, some of them convened by the IAEA, that international co-operation was required, and an IAEA co-ordinated research project (CRP) was recommended. This recommendation was endorsed by the International Nuclear Data Committee, an advisory body for the nuclear data programme of the IAEA. As a consequence, the CRP on the Compilation and Evaluation of Fission Yield Nuclear Data was initiated in 1991, after its scope, objectives and tasks had been defined by a preparatory meeting. -

Electron Capture in Stars

Electron capture in stars K Langanke1;2, G Mart´ınez-Pinedo1;2;3 and R.G.T. Zegers4;5;6 1GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨urSchwerionenforschung, D-64291 Darmstadt, Germany 2Institut f¨urKernphysik (Theoriezentrum), Department of Physics, Technische Universit¨atDarmstadt, D-64298 Darmstadt, Germany 3Helmholtz Forschungsakademie Hessen f¨urFAIR, GSI Helmholtzzentrum f¨ur Schwerionenforschung, D-64291 Darmstadt, Germany 4 National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA 5 Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics: Center for the Evolution of the Elements, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Electron captures on nuclei play an essential role for the dynamics of several astrophysical objects, including core-collapse and thermonuclear supernovae, the crust of accreting neutron stars in binary systems and the final core evolution of intermediate mass stars. In these astrophysical objects, the capture occurs at finite temperatures and at densities at which the electrons form a degenerate relativistic electron gas. The capture rates can be derived in perturbation theory where allowed nuclear transitions (Gamow-Teller transitions) dominate, except at the higher temperatures achieved in core-collapse supernovae where also forbidden transitions contribute significantly to the rates. There has been decisive progress in recent years in measuring Gamow-Teller (GT) strength distributions using novel experimental techniques based on charge-exchange reactions. These measurements provide not only data for the GT distributions of ground states for many relevant nuclei, but also serve as valuable constraints for nuclear models which are needed to derive the capture rates for the arXiv:2009.01750v1 [nucl-th] 3 Sep 2020 many nuclei, for which no data exist yet. -

Star Factories: Nuclear Fusion and the Creation of the Elements

Star Factories: Nuclear Fusion and the Creation of the Elements Science In the River City workshop 3/22/11 Chris Taylor Department of Physics and Astronomy Sacramento State Introductions! Science Content Standards, Grades 9 - 12 Earth Sciences: Earth's Place in the Universe 1.e ''Students know the Sun is a typical star and is powered by nuclear reactions, primarily the fusion of hydrogen to form helium.'' 2.c '' Students know the evidence indicating that all elements with an atomic number greater than that of lithium have been formed by nuclear fusion in stars.'' Three topics tonight: 1) how do we know all the heavier elements are made in stars? (Big Bang theory) 2) How do stars make elements as heavy as or less heavy than iron? (Stellar nucleosynthesis) 3) How do stars make elements heavier than iron? (Supernovae) Big Bang Nucleosynthesis The Big Bang theory predicts that when the universe first formed, the only matter that existed was hydrogen, helium, and very tiny amounts of lithium. If this is true, then all other elements must have been created in stars. Astronomers use spectroscopy to examine the light emitted by distant stars to determine what kinds of atoms are in them. We've learned that most stars contain nearly every element in the periodic table. The spectrum of the Sun In order to measure measure what kinds of atoms were around in the earliest days of the Universe, we look for stars that were made out of fresh, primordial gas. The closest we can get to this is looking at dwarf galaxies, which show extremely low levels of elements heavier than helium. -

Radioactive Decay

North Berwick High School Department of Physics Higher Physics Unit 2 Particles and Waves Section 3 Fission and Fusion Section 3 Fission and Fusion Note Making Make a dictionary with the meanings of any new words. Einstein and nuclear energy 1. Write down Einstein’s famous equation along with units. 2. Explain the importance of this equation and its relevance to nuclear power. A basic model of the atom 1. Copy the components of the atom diagram and state the meanings of A and Z. 2. Copy the table on page 5 and state the difference between elements and isotopes. Radioactive decay 1. Explain what is meant by radioactive decay and copy the summary table for the three types of nuclear radiation. 2. Describe an alpha particle, including the reason for its short range and copy the panel showing Plutonium decay. 3. Describe a beta particle, including its range and copy the panel showing Tritium decay. 4. Describe a gamma ray, including its range. Fission: spontaneous decay and nuclear bombardment 1. Describe the differences between the two methods of decay and copy the equation on page 10. Nuclear fission and E = mc2 1. Explain what is meant by the terms ‘mass difference’ and ‘chain reaction’. 2. Copy the example showing the energy released during a fission reaction. 3. Briefly describe controlled fission in a nuclear reactor. Nuclear fusion: energy of the future? 1. Explain why nuclear fusion might be a preferred source of energy in the future. 2. Describe some of the difficulties associated with maintaining a controlled fusion reaction. -

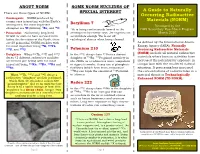

A Guide to Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORM)

ABOUT NORM SOME NORM NUCLIDES OF SPECIAL INTEREST A Guide to Naturally There are three types of NORM: Occurring Radioactive • Cosmogenic – NORM produced by cosmic rays interacting with the Earth’s Materials (NORM) Beryllium 7 atmosphere; the most important Developed by the 3 7 14 examples are H (tritium), Be, and C. 7Be is being continuously formed in the DHS Secondary Reachback Program • Primordial – Sufficiently long-lived atmosphere by cosmic rays. Jet engines can March 2010 NORM for some to have survived from accumulate enough 7Be to set off before the formation of the Earth; there radiological alarms when being cleaned. are 20 primordial NORM nuclides with As defined by the International Atomic the most important being 40K, 232Th, Energy Agency (IAEA), Naturally 235U, and 238U. Polonium 210 Occurring Radioactive Materials • Daughters – When 232Th, 235U and 238U In the 238U decay chain 210Po is a distant (NORM) include all natural radioactive decay 42 different radioactive nuclides daughter of 226Ra. 210Po gained notoriety in materials where human activities have are formed (see below) with the most the 1960s as a radioactive trace component increased the potential for exposure in important being 222Rn, 226Ra, 228Ra and in cigarette smoke. Heavy use of phosphate comparison with the unaltered natural 228 Ac. fertilizers (which have trace amounts of out here. fold Next situation. If processing has increased 226Ra) can triple the amount of 210Po found the concentrations of radionuclides in a When 232Th, 235U and 238U decay a in tobacco. material then it is Technologically radioactive “daughter” nuclide is formed, Enhanced NORM (TE-NORM). -

2.3 Neutrino-Less Double Electron Capture - Potential Tool to Determine the Majorana Neutrino Mass by Z.Sujkowski, S Wycech

DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SPECTROSCOPY AND TECHNIQUE 39 The above conservatively large systematic hypothesis. TIle quoted uncertainties will be soon uncertainty reflects the fact that we did not finish reduced as our analysis progresses. evaluating the corrections fully in the current analysis We are simultaneously recording a large set of at the time of this writing, a situation that will soon radiative decay events for the processes t e'v y change. This result is to be compared with 1he and pi-+eN v y. The former will be used to extract previous most accurate measurement of McFarlane the ratio FA/Fv of the axial and vector form factors, a et al. (Phys. Rev. D 1984): quantity of great and longstanding interest to low BR = (1.026 ± 0.039)'1 I 0 energy effective QCD theory. Both processes are as well as with the Standard Model (SM) furthermore very sensitive to non- (V-A) admixtures in prediction (Particle Data Group - PDG 2000): the electroweak lagLangian, and thus can reveal BR = (I 038 - 1.041 )*1 0-s (90%C.L.) information on physics beyond the SM. We are currently analyzing these data and expect results soon. (1.005 - 1.008)* 1W') - excl. rad. corr. Tale 1 We see that even working result strongly confirms Current P1IBETA event sxpelilnentstatistics, compared with the the validity of the radiative corrections. Another world data set. interesting comparison is with the prediction based on Decay PIBETA World data set the most accurate evaluation of the CKM matrix n >60k 1.77k element V d based on the CVC hypothesis and ihce >60 1.77_ _ _ results