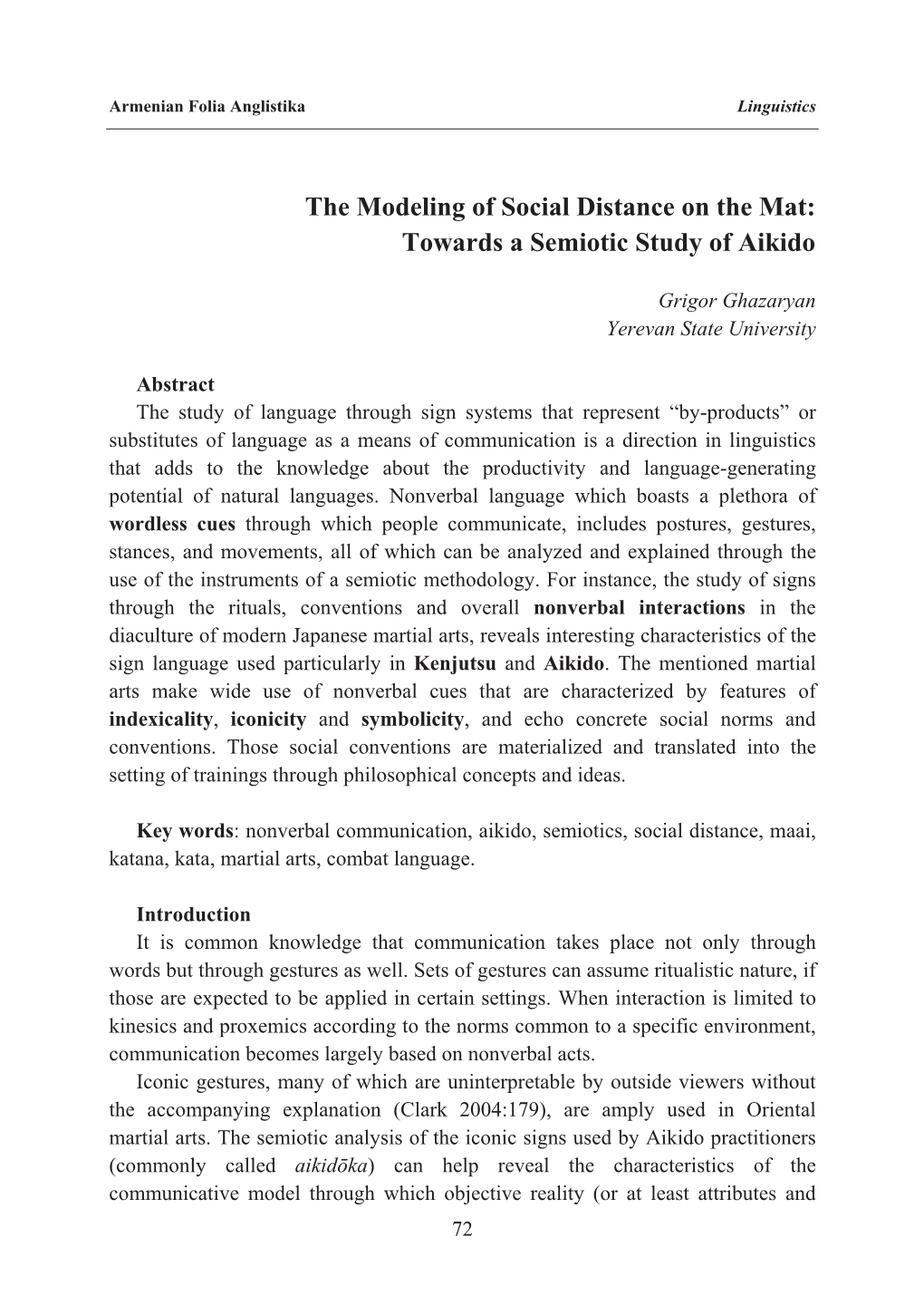

Towards a Semiotic Study of Aikido

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aikido: Filosofía Y Práctica

Aikido: Filosofía y Práctica. INDICE 1. Historia de Japón 1.1. El Período temprano histórico 1.2. El Período Yamato 1.3. El Período Nara 1.4. Los Heian y los Fujiwara 1.5. Los Shogunatos 1.5.1. El Período Kamakura 1.5.2. El Periodo Ashikaga 1.6. El Período de Unificación 1.7. El Período Tokugawa 1.8. El Japón moderno 1.8.1. El Período Meiji 1.8.2. La I Guerra Mundial y los años de entreguerras 1.8.3. La II Guerra Mundial 1.8.4. El Japón de la postguerra 2. Biografía del Fundador del Aikido: Morihei Ueshiba. 2.1. Morihei Ueshiba & Sokaku Takeda 2.2. Morihei Ueshiba & Onisaburo Deguchi 2.3. Morihei Ueshiba & Kisshomaru Ueshiba 2.4. Morihei Ueshiba & Isamu Takeshita 3. Introducción al Aikido 3.1. ¿Qué es Aikido? 3.2 La teoría del Aikido 3.3. Los diferentes estilos en Aikido 3.4. Las competiciones y el Aikido 3.5. La práctica en seiza 3.6. La hakama 3.7. La escala de grados 3.8. ¿Requiere el Aikido más tiempo para dominarlo y aplicarlo que otras artes marciales? 3.9. ¿Aikido u otras artes marciales? 4. Principios de Aikido 4.1. Proyección del Ki 1 4.2. Conoce la mente de tu oponente 4.3. Respeta el Ki de tu oponente 4.4. Ponte en el lugar de tu adversario 4.5. Actúa con confianza 4.6. Centro/ hara 5. Reglas de comportamiento en clase 5.1. El ritual antes de la clase 5.2. El saludo y el uso de los términos japoneses 5.3. -

School of Traditional Martial Arts

School of Traditional Martial Arts ANCIENT THEORY, MODERN PRACTICE Kenshinryu — 3-5 Briggs St Palmwoods Qld — Ph:(6107) 5457 3716 – www.kenshin.com.au Contents LETTER FROM THE HEAD TEACHER ........................................................................................................ 1 KENSHINRYU.................................................................................................................................................. 2 DOJO PHILOSOPHY ....................................................................................................................................... 4 AIKIDO HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................... 5 SHINTO MUSO RYU HISTORY..................................................................................................................... 6 AIKIDO CLASSES ........................................................................................................................................... 7 SHINTO MUSO RYU CLASSES ..................................................................................................................... 7 JUNIOR AIKIDO .............................................................................................................................................. 7 DOJO ETIQUETTE........................................................................................................................................... 8 PRECAUTIONS FOR TRAINING .................................................................................................................. -

No.226 June 2014 AIKIDO YOSHINKAN BRISBANE DOJO Dojo: Facebook: Twitter

No.226 June 2014 AIKIDO YOSHINKAN BRISBANE DOJO Dojo: http://yoshinkan.info Facebook: http://bit.ly/dojofb Twitter: http://twitter.com/YoshinkanAikido May Report New members 3 Total number of adults training 66 Total number of children training 42 Results of Getsurei Shinsa on 30th & 31st May Jun-3rd Kyu Christian McFarland 8th Kyu Andrew Crampton Y2 step Emmanuel Economidis 4th Kyu Roland Thompson 9th Kyu Sai Kiao 4Y8 step Lawrence Monforte 5th Kyu Niklas Casaril Ross Macpherson S5 step Vladimir Roudakov Jared Mifsud Sandy Lokas Janna Malikova 7th Kyu Charles Delaporte Pol O Sleibhin S4 step Lu Jiang Daniel Tagg Pedro Gouvea 8th Kyu Victor Ovcharenko Lily Crampton Janna Malikova Events in June Lu Jiang 1. Sogo Shinsa 2. This Month’s Holiday of Adults’ class th Training starts, Friday 13th 7:15pm~ Queen’s Birthday –Monday 9 June th Steps, Friday 27th June 7:15pm~ Dojo Holiday –Monday 30 June Shinsa, Saturday 28th June 1:00pm~ Coffee Break My excuse –differences in culture A few years ago, a partner of an acquaintance of mine began training at our dojo. She happened to be right next to me during the warming-up at the second or third lesson. When Koho-ukemi practice started she was struggling to get up herself as is very normal for a lot of beginners. Had I not known her personally I would not have paid any attention but because she was someone I knew, I tried to encourage her with the intention of making her feel more enjoyment, feeling sorry for her dealing with the hard exercises. -

Addition to SKDUN Rules of Competition (2013 Third Revision) For

Addition to SKDUN rules of Competition (2013 third revision) JIYU IPPON KUMITE PERFORMANCE AND JUDGING CRITERIA For grading examiners, Instructors, referees and judges, coaches and those who wish to study karate and not just do karate Preamble: The need for students to learn how to fight is implicit in the art of Karate, it is not possible to go straight to Jiyu Kumite because the necessary skills required to be a competent, knowledgeable and competent Kumite Karate-ka are found in the building blocks of the grading syllabus, 1st Gohon Kumite, 2nd Sanbon Kumite, 3rd Kihon Ippon Kumite then Jiyu Ippon Kumite (the “bridges” to knowledgeable Jiyu Kumite). No protective equipment is allowed. There are several aspects to consider, listed below are some of the main points. 1) The attacker is the instigator of movement and of course the attack, if their Maai is incorrect or the intention to make a determined attack is missing then the attack is non existent, the attack must be accompanied by a kiai. 2) The attacker must not chase the defender but focus and impact on the target “where it is” not where it is going to be, for example, if the distance, timing, seeing the moment and speed are correct then success is virtually guaranteed. 3) The attacks should be determined but absolute control should be demonstrated in the event of the defenders unsuccessful block. 4) The correct use of shomen and hanmi must exist throughout from both competitors. 5) The defender must not retreat or run away, they must demonstrate their ability to control the attacker’s distance (maai) and allow the attacker to close the distance and attack. -

Personal Development Student Guide

‘ 北剛柔空⼿道 Karate Studio of Utica Personal Development Student Guide UticaKarate.com Karate Studio of Utica Chief Instructor Profile Kyoshi Shihan Efren Reyes Has well over 30 years of experience practicing and teaching martial arts. He began his Karate training at age 19. No stranger to combative arts since he was already experienced in boxing at the time he was introduced to karate by his older brother. He has groomed and continues to mentor many of our blackbelts both near and far. He holds Kyoshi level certification in Goju-Ryu Karate under the late Sensei Urban and Sensei Van Cliff as well as a 3rd Dan in Aikijutsu under Sensei Van Cliff who has also ranked him master level in Chinese Goju-Ryu. Sensei Urban acknowledged Shihan has the mastery and expertise to be recognized as grand master of his own style of Goju-Ryu since he development of Goju-Ryu had evolved to point of growing his own vision and practice of karate unique to Shihan. This is what is practiced and taught at the Utica Karate. He has also studied Wing Chun in later years to further his understanding and perspective of techniques in close quarters. Shihan has promoted Karate-do through his style of Goju-Ryu under North American Goju karate. Shihan has directed many classes and seminars on various subjects’ ranging from basic self defense to meditation. Karate Studio of Utica Black Belt Instructor Profiles Sensei Philip Rosa Mr. Rosa holds the rank of Sensei (5th degree) and has been practicing Goju-Ryu Karate under Shihan Reyes since 1990. -

Japanese Terms.Indd

Norwalk CommonKendo Dojo Japanese terms used during practice Southeast Japanese Community Center 14615 Gridley Road. Norwalk, ShortCA 90650 Vowels Vowel Combinations [email protected] as in father,m alms ei=e+i sounded as in day e as in pen, red ai=a+i sounded as in alive i as in ink, machine ou=o+u sounded as in float o as in open, ocean au=a+u sounded as in out u as in true, cruel Japanese Words and Phrases English Translations Ohayo gozaimasu Good morning Konnichiwa Hello Konbanwa Good evening Sayonara Goodbye Oyasumi nasai Good night Arigato gozaimashita Thank you very much Onegai shimasu I'm requesting (to practice) Hai Yes Sensei Instructor/Teacher Yudansha Black-belt students Kenshi Kendo students Sempai Elders/Seniors Kouhai Younger/Lower juniors Ichi One Ni Two San Three Shi Four Go Five Roku Six Shichi Seven Hachi Eight Ku/Kyu Nine Ju Ten Kiai Showing your spirit and feeling through your voice Kamae Ready stance in Kendo Chakuza Sit on the floor Seiza Sit properly Mokusou Meditation Yame Stop Naore Return to original position Rei Bow Kiritsu Stand up Keiko Practice Kakari geiko Continuous attack practice Zanshin Mental and physical alertness, especially after completing an attack Norwalk Kendo Dojo Southeast Japanese Community Center 14615 Gridley Road. Norwalk, CA 90650 [email protected] Kendo Terms Japanese English Translations Ashi sabaki Footwork Dan Ranking system for advanced levels (1=lowest, 10=highest); equivalent to black belt in other martial arts Datotsu no kikai Chance of strike Ippon shoubu One point -

Aikido Glossary

Redlands Aikikai Glossary For a more indepth rendering of some of the terms below, please refer to the Student Handbook of the Aikido Schools of Ueshiba In general, each syllable in a Japanese word is pronounced with equal emphasis. Some syllables, though, are hardly pronounced at all (eg. Tsuki is pronounced as “tski”) Techniques The name of each technique is made up of (1) the attack, (2) the defense, and, if applicable, (3) the direction. There are four sets of directional references used in Aikido techniques (Some techniques do not have a specific “direction”): 1. Irimi (eereemee) refers to Yo (Chinese: Yang ) movement which enters through or behind the attacker and Tenkan (tehn-kahn) refers to In (Chinese: Yin ) movement which turns with the attacker’s energy. 2. Omote (ohmoeteh) refer to movements in which nage’s action is mostly in front of the attacker (also "above"), while Ura (oorah) movements take place mostly behind the attacker (also "below"). Omote and Ura also have the meanings of “exoteric” and “esoteric” (secret), respectively. 3. Uchi Mawari (oocheemahwahree) is a turn “inside” the attacker, i.e., within the compass of his arms, while Soto Mawari (sohtoemahwahree) is a turn “outside” the attacker, i.e., beyond the compass of his arms. Hence also Uchi Deshi : inside student, living in the dojo; and Soto Deshi : outside student. 4. Zenshin (zenshin), towards the front; Kotai (kohtie), towards the rear. Attacks: Japanese Word Approximate Pronunciation Approximate Meaning Eri Dori Ehree Doeree Collar Grab Gyakute Dori; Ai -

1400 Coppermine Terrace Baltimore, MD 21209 1

We understand that this would not be possible without our mutual willingness to allow each other the use of our bodies for practice. This is an honor and we never forget that. While pushing ourselves to our own limits we take great care not to harm our partners during Page | 1 class. We believe that it is our job to support each other’s journey toward inner peace and strength. We open our door with this intention in mind. Everyone is encouraged to come watch a class or join us on the mat. I assure you that you will learn something incredible about yourself. Welcome Welcome to Falls Road Aikido! We have three Location intentions for our students Address: 1400 Coppermine Terrace Baltimore, MD 21209 1. Safety Phone: (508) 284-2910 2. Fun Email: [email protected] 3. Transforming into a highly effective http://www.fallsroadaikido.com martial artist. Lead Instructor: Sempai Cara-Michele Nether Falls Road Aikido produces champions in life as well as in the martial arts. Class Schedule Adults: We are a small traditional aikido dojo with a Monday 6:00 – 7:30 pm twist. “How we train in the dojo is exactly the Wednesday 6:00 – 8:00 pm same way we will show up in life” is a driving Sunday 10:00 – 12:00 noon* motto that moves us towards our goals of being *Weapons Class first Sunday of the month the best martial artist that we can be. This 9 – 12:00 noon means that realistic kicks, punches, chokes and even being taken to the ground are a part of our Please Join Us on the Mat! regular training. -

Dojo Information

Aikido Kokikai South Everett Dojo Information Aikido Kokikai South Everett 12322 Hwy 99 #96 Everett, WA 98204 (425) 347-9025 www.everettaikido.com [email protected] 1 Aikido Kokikai South Everett: Dojo Information CONTENTS Welcome to the Dojo..................................................................................................................................................... 3 About Kokikai ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 About Our Dojo .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Training Schedule ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Membership Fees ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Joining Fee ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Recurring Memberships ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Monthly Memberships ......................................................................................................................................... -

Aikido and Spirituality: Japanese Religious Influences in a Martial Art

Durham E-Theses Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art Greenhalgh, Margaret How to cite: Greenhalgh, Margaret (2003) Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk AIK3DO AND SPIRITUALITY: JAPANESE RELIGIOUS INFLUENCES IN A MARTIAL _ ART A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Department of East Asian Studies University of Durham Margaret Greenhalgh December 2003 AUG 2004 COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it may be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Welcome Packet

Welcome to Aikido of San Jose! Thank you for joining us in our training and we hope that we are able to help you along your training as well. Founded in the late 1920s to 1930s by O’Sensei, Morihei Ueshiba, Aikido is a blend of the martial arts that O’Sensei had studied and his spiritual practices at the time. The Aikido name was not adopted until 1942 and the martial art was referred to as “aiki-jiujitsu” and “aiki-budo” before the official naming. The name “Aikido” can be interpreted in many ways - but the purely literal translation would be “the way of unifying energy.” Thus, the practice of Aikido is a martial art in which energies from attacker and defender are unified/blended. There are many reasons to train in a martial art and we are glad you have chosen to practice Aikido. As with any martial art, it is important to remember that each of us are here to improve ourselves through the art, and that it is not a competition. Please always remember to treat your training partners with respect and care. May your journey in the art result in a clearer focus and a better understanding of yourself. In this welcome packet, you will find some information that may be helpful in your journey, but keep in mind that any of the aikidoka at ASJ are always willing to help and answer any questions you may have. Aikido is an art derived from love and gratitude - let that be an anchor to your training and let us all travel this part of our journeys together. -

New Releases April 2019

NEW RELEASES APRIL 2019 BayView Entertainment, LLC • 210 West Parkway, Suite 7, Pompton Plains, NJ 07444 • 201-488-6110 www.bayviewentertainment.com • © 2019 BayView Entertainment, LLC; All Rights Reserved . Street Date: 4/2/2019 SHOTOKAN & SHITO RYU KARATE KATAS FROM SRP: $29.99 WHITE BELT UP TO BLACK BELT Cost: Synopsis: On this DVD Marcus Gutzmer shows you the basic katas in shotokan and shito-ryu karate up to the 1st Dan Black Belt. Shotokan Karate Katas: Heian Shodan, Heian Nidan, Heian Sandan, Heian Yondan, Heian Godan, Bassai Dai, Jion, Kanku Dai. Shito Ryu Karate Katas: Pinan Shodan, Pinan Nidan, Pinan Sandan, Pinan Yondan, Pinan Godan, Bassai Dai, Seienchin. Marcus Gutzmer was born in Kaiserslautern and started doing Karate in Shotokan style category at the age of 6. Over the years Marcus Gutzmer has gotten to know Goju-Ryu, Shito Ryu and Open Style Karate. Since 1990 additionally he has been practicing Combat Arnis and Bo-Jutsu. Titles: Shotokan-Cup Champion, Euro Cup Champion, World Cup Champion. Studio: BayView Entertainment Item #: BAY2591 UPC: 812073025916 Order Date: 3/5/2019 Street Date: 4/2/2019 SRP: $29.99 Rating: NR Screen Format: WS Language English Subtitles: n/a # of Discs / Runtime: 1 disc / 56 mins. Genre: Martial Arts 2 All Marketing, Art and Bonus Features are subject to change Street Date: 4/2/2019 AIKIDO FROM A TO Z BASIC TECHNIQUES VOLUME 1: SRP: $29.99 THE BASICS Cost: Synopsis: The first DVD volume of the educational DVD series, “Aikido from A to Z,” demonstrates the essentials of Aikido. After warm-up gymnastics specifically developed for Aikido (taiso), lessons to drop school (ukemi), to the basic forms of movement (sabaki), to body stances and distance (kamae,maai) are included.