Why Monuments Are Government Speech: the Hard Case of Pleasant Grove City V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Bay Area Economics Draft Report – Study Of

DRAFT REPORT Study of Alternatives to Housing For the Funding of Brooklyn Bridge Park Operations Presented by: BAE Urban Economics Presented to: Brooklyn Bridge Park Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) February 22, 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i Introduction and Approach ........................................................................................... 1 Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) Process ............................................................ 1 Report Purpose and Organization ............................................................................................. 2 Topics Outside the Scope of the CAH and this Report ............................................................. 3 Report Methodology ................................................................................................................. 4 Limiting Conditions .................................................................................................................. 4 Park Overview and the Current Plan ............................................................................ 5 The Park Setting and Plan ......................................................................................................... 5 Park Governance ....................................................................................................................... 6 The Current Financing Plan ..................................................................................................... -

Masters Thesis

WHERE IS THE PUBLIC IN PUBLIC ART? A CASE STUDY OF MILLENNIUM PARK A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corrinn Conard, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. James Sanders III, Advisor Advisor Professor Malcolm Cochran Graduate Program in Art Education ABSTRACT For centuries, public art has been a popular tool used to celebrate heroes, commemorate historical events, decorate public spaces, inspire citizens, and attract tourists. Public art has been created by the most renowned artists and commissioned by powerful political leaders. But, where is the public in public art? What is the role of that group believed to be the primary client of such public endeavors? How much power does the public have? Should they have? Do they want? In this thesis, I address these and other related questions through a case study of Millennium Park in Chicago. In contrast to other studies on this topic, this thesis focuses on the perspectives and opinions of the public; a group which I have found to be scarcely represented in the literature about public participation in public art. To reveal public opinion, I have conducted a total of 165 surveys at Millennium Park with both Chicago residents and tourists. I have also collected the voices of Chicagoans as I found them in Chicago’s major media source, The Chicago Tribune . The collection of data from my research reveal a glimpse of the Chicago public’s opinion on public art, its value to them, and their rights and roles in the creation of such endeavors. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

The Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park Is an Ingenious

ACrowning Achievement The Crown Fountain in Chicago’s Millennium Park is an ingenious fusion of artistic vision and high-tech water effects in which sculptor Jaume Plensa’s creative concepts were brought to life by an interdisciplinary team that included the waterfeature designers at Crystal Fountains. Here, Larry O’Hearn describes how the firm met the challenge and helped give Chicago’s residents a defining landmark in glass, light, water and bright faces. 50 WATERsHAPES ⅐ APRIL 2005 ByLarry O’Hearn In July last year, the city of Chicago unveiled its newest civic landmark: Millennium Park, a world-class artistic and architec- tural extravaganza in the heart of downtown. At a cost of more than $475 million and in a process that took more than six years to complete, the park transformed a lakefront space once marked by unsightly railroad tracks and ugly parking lots into a civic showcase. The creation of the 24.5-acre park brought together an unprecedented collection of world-class artists, architects, urban planners, landscape architects and designers including Frank Gehry, Anish Kapoor and Kathryn Gustafson. Each con- tributed unique designs that make powerful statements about the ambition and energy that define Chicago. One of the key features of Millennium Park is the Crown Fountain. Designed by Jaume Plensa, the Spanish- born sculptor known for installations that focus on human experiences that link past, present and fu- ture and for a philosophy that says art should not simply decorate an area but rather should trans- form and regenerate it, the Crown Fountain began with the notion that watershapes such as this one need to be gathering places. -

The Global Edge: an Agenda for Chicago’S Future Issues Through Contributions to Opinion and Policy Formation, Leadership Dialogue, and Public Learning

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, founded in 1922 as The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, is a leading independent, nonpartisan organization committed to influencing the discourse on global Future Chicago’s for An Agenda The Global Edge: issues through contributions to opinion and policy formation, leadership dialogue, and public learning. The Global Edge: An Agenda for Chicago’s Future Report of an Independent Study Group Michael H. Moskow, Henry H. Perritt, Jr., and Adele Simmons, Cochairs Sponsored by 332 South Michigan Avenue Suite 1100 Chicago, Illinois 60604 thechicagocouncil.org SPINE The Global Edge: An Agenda for Chicago’s Future RepoRt of an Independent Study GRoup Michael H. Moskow, Henry H. Perritt, Jr., and Adele Simmons, Cochairs SponSoRed by The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is a leading independent, nonpartisan organi- zation committed to influencing the discourse on global issues through contributions Study Group Cochairs to opinion and policy formation, leadership dialogue, and public learning. Michael H. Moskow The Chicago Council provides members, specialized groups, and the general public Senior Fellow for the Global Economy with a forum for the consideration of significant international issues and their bear- ing on American foreign policy. In addition to remaining the premier platform in the The Chicago Council on Global Affairs Midwest for international leaders in foreign policy, The Chicago Council strives to take the lead in gaining recognition for Chicago as an international business center Henry H. Perritt, Jr. for the corporate community and to broaden and deepen the Council’s role in the Professor community. Chicago-Kent College of Law THE CHICAGO COUNCIL TAKES NO INSTITUTIONAL POSITION ON POLICY ISSUES AND HAS NO AFFILIATION WITH THE U.S. -

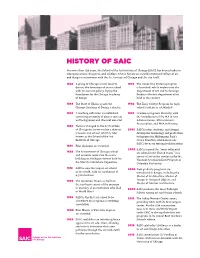

History of Saic

HISTORY OF SAIC For more than 150 years, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) has been a leader in educating artists, designers, and scholars. SAIC’s history as a world-renowned college of art and design is interwoven with the Art Institute of Chicago and the city itself. 1866 A group of Chicago artists meet to 1972 The Generative Systems program discuss the formation of an art school is launched, which evolves into the with its own art gallery, laying the Department of Art and Technology foundation for the Chicago Academy Studies—the first department of its of Design kind in the country 1869 The State of Illinois grants the 1982 The Early College Program for high Chicago Academy of Design a charter school students is established 1872 A teaching collection is established, 1993 Graduate programs diversify, with consisting primarily of plaster casts as the introduction of the MA in Arts well as Egyptian and Classical material Administration, MS in Historic Preservation, and MFA in Writing 1882 Name is changed to the Art Institute of Chicago to accommodate a distinct 2001 SAIC faculty, students, and alumni museum and school, which is later develop the technology and production known as the School of the Art techniques for Millennium Park’s Institute of Chicago Crown Fountain, which increases SAIC’s focus on external collaborations 1891 First diplomas are awarded 2002 SAIC is named the “most influential 1893 The Art Institute of Chicago school art school in the United States” in a and museum move into the iconic survey of art -

What's out There Chicago Kid's Guide

The Cultural Landscape Foundation What’s Out There Chicago Kid’s Guide + Activities Welcome to the What’s Out There Chicago Kid’s Guide! Chicago, a city of celebrated, well-known architecture, is also home to remarkable and pioneering works of landscape architecture, from the Prairie style epitomized by Alfred Caldwell’s Lily Pool and Jens Jensen’s Columbus Park to significant 20th century landscapes that include the roof garden atop The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) the Modernist Lake Point Tower and Dan The 12-year old Cultural Landscape Foundation provides Kiley’s geometric design for the Art Institute people with the ability to see, understand and value of Chicago’s South Garden. landscape architecture and its practitioners, in the way many people have learned to do with buildings Visit the What’s Out There Chicago website and their designers. Through its Web site, lectures, outreach and publishing, TCLF broadens the support and www.tclf.org/landscapes/wot-weekend-chicago understanding for cultural landscapes nationwide to help to learn more... safeguard our priceless heritage for future generations. The Cultural Landscape Foundation 1909 Que Street NW, Second Floor This Kid’s Guide is part of TCLF’s ongoing Washington, DC 20009 Cultural Landscapes as Classrooms (CLC) (t) 202.483.0553 (f) 202.483.0761 series, which teaches people to “read” the www.tclf.org landscapes and cityscapes that are part of their surroundings, to understand how changes affect these special places, and to become better stewards of this shared cultural landscape heritage. The booklet is filled with fun activities, engaging games, and things to look for at 18 Chicago sites. -

Millennium Park Chicago, Illinois

2009 RUDY BRUNER AWARD: Silver Medal Winner Millennium Park Chicago, Illinois ©BRUNER FOUNDATION, INC. ~ www.brunerfoundation.org SILVER MEDAL WINNER MILLENNIUM PARK © City of Chicago / GRC Aerial view of Millennium Park 88 2009 RUDY BRUNER AWARD Millennium Park at-a-Glance WHAT IS MILLENNIUM PARK? PROJECT GOALS v A 24.5-acre park with venues for performance, art, v To transform the commuter railroad tracks, surface parking sculpture, architecture and landscape architecture, located and degraded parkland in the northwest corner of Grant Park between Chicago’s lakefront and the central business into a landscaped venue for free public programming, district (the Loop). concerts, and events v The transformation of a dilapidated ground-level parking v To create a permanent home for the Grant Park Music Festival lot and rail yard into what may be the world’s largest “green v To provide one-of-a-kind public art spaces as a “gift” to all roof,” covering two multi-level parking lots with a total of the citizens of Chicago from patrons who have made their 4,000 cars, and commuter rail line. fortunes in the city v A park with twelve installations created by well-known artists v To lay the foundation for future private residential and and designers that supports over 500 free cultural programs commercial development in the area each year, forming what the Chicago Tribune art reporter Chris Jones called “arguably the most expansive cultural project in Chicago since the 1893 Columbian Exposition.” v A catalyst for economic impacts, including estimated increases in nearby real estate values that total $1.4 billion and an increase in tourism revenues of $2.6 billion over a projected year period. -

Projects in Public Space

JAUME PLENSA l PROJECTS IN PUBLIC SPACE www.jaumeplensa.com PACIFIC SOUL, 2018 Site: Pacific Gate, San Diego, California Commissioned by: BOSA Development and Fine Arts Service LLC LOVE, 2017 Site: Stationsplein, Leeuwarden, Frisia, Netherlands Commissioned by: Leeuwarden Fryslând 2018 – Culturele Hoofdstad van Europa BANGKOK SOUL, 2017 Site: MahaNakhon Building, Bangkok, Thailand SOURCE, 2017 Site: Bonaventure Gateway, Montréal, Canada Commissioned by: City of Montreal's Public Art Bureau for 375th Anniversary Patrons: France Chrétien Desmarais and André Desmarais LOOKING INTO MY DREAMS, AWILDA, 2012 Site: PAMM-Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami, USA, 2017 1004 Portraits. 10th Anniversary of the Crown Fountain, Millennium Park, Chicago (2014-2015) Olhar nos meus sonhos, Awilda. Enseada Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (2012) POSSIBILITIES, 2016 Site: Lotte World Tower, Seoul, South Korea Commissioned by: Lotte Art Project, Seoul, South Korea, 2015 CARMELA, 2015 Site: Sant Pere més Alt – Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, Spain ROOTS, 2014 Site: Toranomon Hills, Tokyo, Japan Commissioned by: Mori Building Corporation, Tokyo, 2014 HOUSE OF KNOWLEDGE, 2008 Site: Textile Fashion Center, Borås University, Borås, Sweden Commissioned by: Borås Staat, Sweden, 2014 ECHO, 2011 Site: Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, USA A gift from Barney A. Ebsworth Collection, 2014 7 POETES, 2014 Site: Plaza Lidia Armengol Vila, Andorra la Vella, Andorra Commissioned by: Banca Privada de Andorra, 2013 WONDERLAND, 2012 Site: The Bow, Calgary, -

Jaume Plensa

Jaume Plensa Private Dreams 1004 Portraits Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago Millennium Park, Chicago June 12 - September 27, 2014 June 18, 2014 - October 2015 Artist Talk at AIC: June 16, 6-7pm Richard Gray Gallery is pleased to announce an exhibition of recent sculpture by Jaume Plensa in a new range of media at their Chicago space. The exhibition coincides with a new public art installation of works by the artist in Millennium Park on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Plensa’s acclaimed Crown Fountain. Both projects continue Plensa’s continued focus on the human figure, specifically the head as a sanctuary for dreams and hope. Plensa will give a lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago on June 16 at 6pm; the event is free and open to the public. Digital rendering Looking Into My Dreams, Awilda Millennium Park, Chicago Millennium Park, Chicago Plensa’s solo exhibition 1004 Portraits, celebrating the 10th anniversary of Millennium Park, will be on view June 18, 2014 through December 2015 in two locations in the park. The four sculptural portraits, ranging from 23 to 39 feet tall, continue the story of Plensa’s original 1000 video portraits of local Chicago residents that have illuminated the Crown Fountain since 2004. Looking Into My Dreams, Awilda, stands at the entrance to Millennium Park (Madison Street at Michigan Avenue); its surreal and majestic presence bridging the frenetic energy and distractions of city life with the tranquility of the park. Magnificent in scale, Awilda’s beauty, power, and serenity encourages people to stop and join the moment of quiet contemplation.