University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

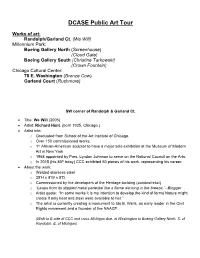

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza Lollapalooza returns with four full days in Grant Park August 3-6, 2017. This four-day extravaganza will transform the jewel of Chicago into a mecca of music, food, art, and fashion featuring over 170 bands on eight stages, including Chance The Rapper, The Killers, Muse, Arcade Fire, The xx, Lorde, blink-182, DJ Snake, and Justice, and many more. Lollapalooza will host 100,000 fans each day, and with so much activity, we wanted to provide some top highlights: •SAFETY FIRST: In case of emergency, we urge attendees to be alert to safety messaging coming from the following sources: • Push Notifications through The Official Lollapalooza Mobile App available on Android and iOS • Video Screens at the Main Entrance, North Entrance, and Info Tower by Buckingham Fountain • Video Screens at 4 Stages – Grant Park, Bud Light, Lake Shore and Perry’s • Audio Announcements at All Stages • Real-time updates on Lollapalooza Twitter, Facebook and Instagram In the event of a weather evacuation, all attendees should follow the instructions of public safety officials. Festival patrons can exit the park to the lower level of one of the following shelters: • GRANT PARK NORTH 25 N. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60602 Underground Parking Garage (between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • GRANT PARK SOUTH 325 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 Underground Parking Garage (between Jackson and Van Buren) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • MILLENIUM LAKESIDE 5 S. Columbus Drive Chicago, IL 60603 Underground Parking Garage (Columbus between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan For a map of shelter locations and additional safety information, visit www.lollapalooza.com/safety. -

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago’s Parks by Julia S. Bachrach, Chicago Park District Historian In 1909, Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) and Edward Bennett published the Plan of Chicago, a seminal work that had a major impact, not only on the city of Chicago’s future development, but also to the burgeoning field of urban planning. Today, govern- ment agencies, institutions, universities, non-profit organizations and private firms throughout the region are coming together 100 years later under the auspices of the Burnham Plan Centennial to educate and inspire people throughout the region. Chicago will look to build upon the successes of the Plan and act boldly to shape the future of Chicago and the surrounding areas. Begin- ning in the late 1870s, Burnham began making important contri- butions to Chicago’s parks, and much of his park work served as the genesis of the Plan of Chicago. The following essay provides Daniel Hudson Burnham from a painting a detailed overview of this fascinating topic. by Zorn , 1899, (CM). Early Years Born in Henderson, New York in 1846, Daniel Hudson Burnham moved to Chi- cago with his parents and six siblings in the 1850s. His father, Edwin Burnham, found success in the wholesale drug busi- ness and was appointed presidet of the Chicago Mercantile Association in 1865. After Burnham attended public schools in Chicago, his parents sent him to a college preparatory school in New England. He failed to be accepted by either Harvard or Yale universities, however; and returned Plan for Lake Shore from Chicago Ave. on the north to Jackson Park on the South , 1909, (POC). -

Art and Economics in the City

Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City Urban Studies Caterina Benincasa, art historian, is founder of Polyhedra (a nonprofit organi- zation focused on the relationship between art and science) and of the Innovate Heritage project aimed at a wide exchange of ideas and experience among scho- lars, artists and pratictioners. She lives in Berlin. Gianfranco Neri, architect, teaches Architectural and Urban Composition at Reggio Calabria “Mediterranea” University, where he directs the Department of Art and Territory. He extensively publishes books and articles on issues related to architectural projects. In 2005 he has been awarded the first prize in the international competition for a nursery in Rome. Michele Trimarchi (PhD), economist, teaches Public Economics (Catanzaro) and Cultural Economics (Bologna). He coordinates the Lateral Thinking Lab (IED Rome), is member of the editoral board of Creative Industries Journal and of the international council of the Creative Industries Federation. Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City New Cultural Maps An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-4214-2. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.know- ledgeunlatched.org. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. -

Jaume Plensa Solo Exhibitions

JAUME PLENSA l SOLO EXHIBITIONS (Selection) www.jaumeplensa.com 2021 Slowness. Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden The True Portrait. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris (online show) 2020 La Llarga Nit. Galeria Senda, Barcelona, Spain Nocturne. Gray Warehouse, Chicago, Illinois, USA Jaume Plensa. Plaza del Estadio de la Cerámica, Villarreal, Castellón, Spain Jaume Plensa, Invisibles. Gray Gallery, Chicago, viewing room (online show) Jaume Plensa. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris (online show) Jaume Plensa: April is the cruelest month. Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, viewing room (online show) 2019 Jaume Plensa. Jakobshallen – Galerie Scheffel, Bad Homburg, Germany Jaume Plensa. Plaça del Congrés Eucarístic, Elche, Alicante, Spain Behind the Walls / Detrás del Muro. Organized by MUNAL–Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL–Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura in collaboration with Fundación Callia, Ciudad de Mexico Jaume Plensa. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France Talking Continents. Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Jaume Plensa. MMOMA–Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow, Russia Jaume Plensa. Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències, Valencia, Spain Jaume Plensa. Museum Beelden aan Zee, The Hague, Netherlands Jaume Plensa a Montserrat. Museu de Montserrat, Abadia de Montserrat, Barcelona, Spain Talking Continents. Telfair Museums, Jepson Center for the Arts, Savannah, Georgia, USA Jaume Plensa. Galería Pilar Serra, Madrid, Spain Jaume Plensa, Nouvelles estampes. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France 2018 Jaume Plensa. MACBA–Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Invisibles. Palacio de Cristal, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain Talking Continents. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee, USA Jaume Plensa. Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden La Música Gráfica de Jaume Plensa. -

Bay Area Economics Draft Report – Study Of

DRAFT REPORT Study of Alternatives to Housing For the Funding of Brooklyn Bridge Park Operations Presented by: BAE Urban Economics Presented to: Brooklyn Bridge Park Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) February 22, 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i Introduction and Approach ........................................................................................... 1 Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) Process ............................................................ 1 Report Purpose and Organization ............................................................................................. 2 Topics Outside the Scope of the CAH and this Report ............................................................. 3 Report Methodology ................................................................................................................. 4 Limiting Conditions .................................................................................................................. 4 Park Overview and the Current Plan ............................................................................ 5 The Park Setting and Plan ......................................................................................................... 5 Park Governance ....................................................................................................................... 6 The Current Financing Plan ..................................................................................................... -

Masters Thesis

WHERE IS THE PUBLIC IN PUBLIC ART? A CASE STUDY OF MILLENNIUM PARK A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corrinn Conard, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. James Sanders III, Advisor Advisor Professor Malcolm Cochran Graduate Program in Art Education ABSTRACT For centuries, public art has been a popular tool used to celebrate heroes, commemorate historical events, decorate public spaces, inspire citizens, and attract tourists. Public art has been created by the most renowned artists and commissioned by powerful political leaders. But, where is the public in public art? What is the role of that group believed to be the primary client of such public endeavors? How much power does the public have? Should they have? Do they want? In this thesis, I address these and other related questions through a case study of Millennium Park in Chicago. In contrast to other studies on this topic, this thesis focuses on the perspectives and opinions of the public; a group which I have found to be scarcely represented in the literature about public participation in public art. To reveal public opinion, I have conducted a total of 165 surveys at Millennium Park with both Chicago residents and tourists. I have also collected the voices of Chicagoans as I found them in Chicago’s major media source, The Chicago Tribune . The collection of data from my research reveal a glimpse of the Chicago public’s opinion on public art, its value to them, and their rights and roles in the creation of such endeavors. -

October 31, 2019 by ELECTRONIC MAIL Mark Kelly, Commissioner

October 31, 2019 BY ELECTRONIC MAIL Mark Kelly, Commissioner Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events 78 E. Washington St., 4th Floor Chicago, IL 60602 [email protected] Re: Unconstitutional Regulation of Millennium Park Dear Mr. Kelly: I write regarding the conduct of security personnel at Refuse Fascism’s October 26, 2019 protest in Millennium Park (the “Park”). Based on witness accounts, Park security made unconstitutional demands of protesters, some of which were based on unconstitutional provisions of the August 26, 2019 Millennium Park Rules (the “Rules”) promulgated by the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE). 1 I ask for your assurances that such restrictions will not be imposed at future protests, including Refuse Fascism’s demonstrations planned for the next three Saturdays. Public parks are traditional public forums that “have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions.” Perry Ed. Assn. v. Perry Local Educators' Assn., 460 U.S. 37, 45 (1983) (quoting Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307 U.S. 496, 515 (1939)). In such places, the government’s authority to restrict speech is limited to “regulations of the time, place, and manner of expression which are content-neutral, are narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest, and leave open ample alternative channels of communication.” Perry, 460 U.S. at 45. On October 26, Park security officers went well beyond the government’s constitutional authority to regulate speech in a public park. -

Strategic Plan

STRATEGIC PLAN FOR REALIZING THE WATERFRONT SEATTLE VISION Prepared for the Mayor of Seattle and the Seattle City Council by the Central Waterfront Committee – July 2012 Created in collaboration with CONTRIBUTORS & CONTENTS “When you look at a city, it’s like reading the hopes, aspirations and pride of everyone who built it.” – Hugh Newell Jacobsen Contributors The Strategic Plan was developed by the volunteer community representatives and leaders who make up the Central Waterfront Committee. The Committee was created by the City of Seattle to advise the Mayor and City Council on the Waterfront Improvement Program, with broad oversight of design, financing, public engagement, and long-term operations and maintenance. Central Waterfront Committee Executive Committee Charley Royer, co-chair Charley Royer, co-chair Maggie Walker, co-chair Maggie Walker, co-chair Tom Bancroft Patrick Gordon Carol Binder Mark Reddington Mahlon Clements David Freiboth Toby Crittenden Ed Medeiros Bob Davidson Gerry Johnson Bob Donegan John Nesholm Rollin Fatland Carol Binder Erin Fletcher (Slayton) Bob Davidson Ben Franz-Knight David Freiboth Design Oversight Subcommittee Gary Glant Patrick Gordon, co-chair Patrick Gordon Mark Reddington, co-chair Craig Hanway Bob Donegan Gerry Johnson Cary Moon Greg Johnson Vlad Oustimovitch Bob Klein Brian Steinburg Alex Kochan Martha Wyckoff Ed Medeiros Rebecca Barnes, Advisor Dave Meinert Liz Dunn, Advisor Nate Miles Jeff Hou, Advisor Cary Moon Jon Houghton, Advisor John Nesholm Chris Rogers, Advisor Jan O’Connor Vlad Oustimovitch -

Jaume Plensa: Talking SAVANNAH

VISUAL ARTS Jaume Plensa: Talking SAVANNAH Continents Fri, March 01– Sun, June 09, 2019 Venue Jepson Center for the Arts, 207 W York St, Savannah, GA 31401 View map Admission Buy tickets More information Telfair Museums Credits Presented by Telfair Museums. Image: Talking Continents by Jaume Plensa, 2013 (photo by David Jaume Plensa presents large-scale sculptures and Nevala) installations that use language, history, literature, and psychology to draw attention to the barriers that separate and divide humanity. In Talking Continents, Jaume Plensa (Spanish, b. 1955) used stainless steel to create a floating archipelago of 19 cloud-like shapes. The biomorphic forms are made with die-cut letters taken from nine different languages that refuse to come together as words, existing instead as abstract forms, and also arbitrary signs and signifiers. Many of the suspended sculptures appear as orbs or islands, while others include human figures in pensive, vulnerable postures. The sculptures speak to the diversity of language and culture, but also gesture toward global interconnectedness as a path to tolerance and acceptance. Visitors are encouraged to tap into the artist’s notion of universal understanding by thinking about the ways in which we are linked together as a collective humanity. ABOUT JAUME PLENSA Born in 1955 in Barcelona, Jaume Plensa is one of the world’s foremost sculptors with international exhibitions and over thirty public projects spanning the globe in such cities as Chicago, Dubai, London, Liverpool, Montreal, Nice, San Diego, Tokyo, Toronto, and Vancouver. Plensa’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at museums Embassy of Spain – Cultural Office | 2801 16th Street, NW, Washington, D.C.