Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

August Highlights at the Grant Park Music Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jill Hurwitz,312.744.9179 [email protected] AUGUST HIGHLIGHTS AT THE GRANT PARK MUSIC FESTIVAL A world premiere by Aaron Jay Kernis, an evening of mariachi, a night of Spanish guitar and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on closing weekend of the 2017 season CHICAGO (July 19, 2017) — Summer in Chicago wraps up in August with the final weeks of the 83rd season of the Grant Park Music Festival, led by Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Carlos Kalmar with Chorus Director Christopher Bell and the award-winning Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park. Highlights of the season include Legacy, a world premiere commission by the Pulitzer Prize- winning American composer, Aaron Jay Kernis on August 11 and 12, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and acclaimed guest soloists on closing weekend, August 18 and 19. All concerts take place on Wednesday and Friday evenings at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday evenings at 7:30 p.m. (Concerts on August 4 and 5 move indoors to the Harris Theater during Lollapolooza). The August program schedule is below and available at www.gpmf.org. Patrons can order One Night Membership Passes for reserved seats, starting at $25, by calling 312.742.7647 or going online at gpmf.org and selecting their own seat down front in the member section of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Membership support helps to keep the Grant Park Music Festival free for all. For every Festival concert, there are seats that are free and open to the public in Millennium Park’s Seating Bowl and on the Great Lawn, available on a first-come, first-served basis. -

This Is Chicago

“You have the right to A global city. do things in Chicago. A world-class university. If you want to start The University of Chicago and its a business, a theater, namesake city are intrinsically linked. In the 1890s, the world’s fair brought millions a newspaper, you can of international visitors to the doorstep of find the space, the our brand new university. The landmark event celebrated diverse perspectives, backing, the audience.” curiosity, and innovation—values advanced Bernie Sahlins, AB’43, by UChicago ever since. co-founder of Today Chicago is a center of global The Second City cultures, worldwide organizations, international commerce, and fine arts. Like UChicago, it’s an intellectual destination, drawing top scholars, companies, entrepre- neurs, and artists who enhance the academic experience of our students. Chicago is our classroom, our gallery, and our home. Welcome to Chicago. Chicago is the sum of its many great parts: 77 community areas and more than 100 neighborhoods. Each block is made up CHicaGO of distinct personalities, local flavors, and vibrant cultures. Woven together by an MOSAIC OF extensive public transportation system, all of Chicago’s wonders are easily accessible PROMONTORY POINT NEIGHBORHOODS to UChicago students. LAKEFRONT HYDE PARK E JACKSON PARK MUSEUM CAMPUS N S BRONZEVILLE OAK STREET BEACH W WASHINGTON PARK WOODLAWN THEATRE DISTRICT MAGNIFICENT MILE CHINATOWN BRIDGEPORT LAKEVIEW LINCOLN PARK HISTORIC STOCKYARDS GREEK TOWN PILSEN WRIGLEYVILLE UKRAINIAN VILLAGE LOGAN SQUARE LITTLE VILLAGE MIDWAY AIRPORT O’HARE AIRPORT OAK PARK PICTURED Seven miles UChicago’s home on the South Where to Go UChicago Connections south of downtown Chicago, Side combines the best aspects n Bookstores: 57th Street, Powell’s, n Nearly 60 percent of Hyde Park features renowned architecture of a world-class city and a Seminary Co-op UChicago faculty and graduate alongside expansive vibrant college town. -

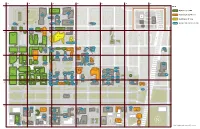

I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park

Jackson Park Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) March 2018 – Data and Community Input Report Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital 3 B. Defining Community for the CHNA 3 C. Community Health Needs Assessment Methods/Process 6 II. Health Status in the Community – Health Indicator Data 7 A. Social, Economic, and Structural Determinants of Health 7 B. Behavioral Health – Mental Health and Substance Use 19 C. Chronic Disease 24 D. Access to Care 39 III. Health Status in the Community – Community & Stakeholder Input 46 A. Community Focus Groups 46 B. Key Informant Interviews 49 IV. Health Status in the Community – Maps of Community Resources 51 V. Summary of Jackson Park Hospital’s Community Health 60 Implementation Activities – 2015-2018 A. Senior Healthcare Program 60 B. Community Partnerships and Outreach 61 C. Outpatient Services 62 D. In Development – Substance Abuse Program 63 Appendix A. Written Comments from Focus Group Participants 63 Appendix B. Focus Group Questions 64 2 I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital Jackson Park Hospital & Medical Center is a 256-bed short-term comprehensive acute care facility serving the south side of Chicago for nearly 100 years. The hospital offers full medical, surgical, obstetric, psychiatric, and medical stabilization (detox) services as well as medical sub-specialties including cardiology, pulmonary, gastrointestinal disease, renal, orthopedics, ENT, ophthalmology, infectious disease, HIV, hematology/oncology and geriatrics. Quality ambulatory care is provided onsite through the family medicine center and senior health center. The hospital also provides medical education and training through its family medicine residency program and several affiliated medical schools. -

Les Bains-Douches Municipaux De La Ville De Paris

Les bains-douches municipaux de la Ville de Paris I. Des bains publics aux bains-douches Aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, les bains publics de Paris sont encore majoritairement des lieux de plaisir et de divertissement raffinés1, réservés à une élite aristocratique, à l’image des pittoresques « bains chinois » construits en 1787 par Nicolas Lenoir sur le boulevard des Italiens. Cependant, l’industrialisation et l’urbanisation croissante de la capitale s’accompagnent d’un cortège de maux, promiscuité, insalubrité, propagation des épidémies - le choléra frappe la ville à plusieurs reprises dès 1832 – qui rendent nécessaire l’élaboration d’une véritable politique d’hygiène sociale en faveur des classes populaires. Cette dernière, bien étudiée par Fabienne Chevallier2, emprunte alors deux directions : une action visant à réglementer les conditions de l’habitat, avec la loi sur les logements insalubres (13 avril 1850) et un important effort de constructions, entrepris par un Etat-Providence en gestation. Dans ce domaine, comme dans celui des logements ouvriers3, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, influencé par son séjour d’exil en Angleterre, montre l’exemple. En 1849, le chimiste Jean- Baptiste Dumas, qu’il nomme Ministre du Commerce et de l’Agriculture, confie à une commission ministérielle la responsabilité d’établir un rapport sur les établissements de bains publics anglais gratuits ou à prix réduits. Il démontre la qualité des réalisations, au bénéfice de la classe ouvrière qui s’y rend « au moins une fois par semaine »4. Le 3 février 1851 est donc voté par l’Assemblée nationale un crédit extraordinaire de 600 000 francs pour encourager les communes à créer des établissements modèles de bains et de lavoirs publics gratuits ou à prix réduits, grâce à une subvention de l’Etat pouvant atteindre les deux tiers de leur financement. -

Report and Opinion

Report and Opinion Concerning the Impact of the Proposed Obama Presidential Center on the Cultural Landscape of Jackson Park, Chicago, Illinois Including the Project’s Compatibility with Basic Policies of the Lakefront Plan of Chicago and the Purposes of the Lake Michigan and Chicago Lakefront Protection Ordinance By: Malcolm D. Cairns, FASLA Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 15, 2018 Assessing the Effect of the Proposed Obama Presidential Center on the Historic Landscape of Jackson Park Prepared by: Malcolm Cairns, FASLA; Historic Landscape Consultant For: The Barack Obama Foundation Date: May 15, 2018 Statement of purpose and charge: To develop the historic landscape analysis that places the proposal to locate the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago’s Jackson Park in its proper historic context. This investigation was undertaken at the request of Richard F. Friedman of the law firm of Neal & Leroy, LLC, on behalf of the Barack Obama Foundation. The assignment was to investigate the proposed Obama Presidential Center master plan and to assess the effect of the project on the historic cultural landscape of Jackson Park, Chicago, a park listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This investigation has necessitated a thorough review of the cultural landscape history of Jackson Park, the original South Park, of which Jackson Park was an integral part, and of the history of the Chicago Park and Boulevard system. Critical in this landscape research were previous studies which resulted in statements of historic landscape significance and historic integrity, studies which listed historic landscape character-defining elements, and other documentation which provided both large and small scale listings of historic landscape form, structure, detail, and design intent which contribute to the historic character of the Park. -

Norrbro Och Strömparterren

Norrbro och Strömparterren - - Stockholms Stadsmuseum augusti 2006 Samlingsavdelningen/Faktarumsenheten Framsidans målning: Klas Lundkvist Anna Palm: Utsikt över Strömmen mot Slottet från Södra Blasieholmshamnen, 1890-talet e-post: beskuren (originalets storlek 122 x 58 cm), [email protected] akvarell, INV NR SSM 0002325 (K 105) telefon: 508 31 712 - - Innehåll Uppdraget Stockholms Trafikkontor planerar för en omfattande Uppdraget ........................................................................................................ renovering av Norrbro. Åtgärderna innebär grundför- Sammanfattning .............................................................................................. 4 stärkning, tätning och fasadrenovering av delen över Platsens betydelse i staden och landet ............................................................ 4 Helgeandsholmen samt förnyelse av kör- och gångytor Norrbro idag .................................................................................................... 5 över hela Norrbro. I planeringen ingår även en översyn Gällande planer och lagstiftning ..................................................................... 7 av Strömparterrens parkyta. Stockholms stadsmuseum Kunskapsläget ................................................................................................. 7 har av Trafikkontoret genom Åsa Larsson, projektle- Kartor över Norrströms, Helgeandsholmens och broarnas utveckling ........... 8 dare Norrbro, och Bodil Hammarberg, projektledare Helgeandsholmen -

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 Update II August 18, 2014

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 update II August 18, 2014 Dear Friends, The Streeterville Neighborhood Plan (“SNP”) was originally written in 2005 as a community plan written by a Chicago community group, SOAR, the Streeterville Organization of Active Resi- dents. SOAR was incorporated on May 28, 1975. Throughout our history, the organization has been a strong voice for conserving the historic character of the area and for development that enables divergent interests to live in harmony. SOAR’s mission is “To work on behalf of the residents of Streeterville by preserving, promoting and enhancing the quality of life and community.” SOAR’s vision is to see Streeterville as a unique, vibrant, beautiful neighborhood. In the past decade, since the initial SNP, there has been significant development throughout the neighborhood. Streeterville’s population has grown by 50% along with new hotels, restaurants, entertainment and institutional buildings creating a mix of uses no other neighborhood enjoys. The balance of all these uses is key to keeping the quality of life the highest possible. Each com- ponent is important and none should dominate the others. The impetus to revising the SNP is the City of Chicago’s many new initiatives, ideas and plans that SOAR wanted to incorporate into our planning document. From “The Pedestrian Plan for the City”, to “Chicago Forward”, to “Make Way for People” to “The Redevelopment of Lake Shore Drive” along with others, the City has changed its thinking of the downtown urban envi- ronment. If we support and include many of these plans into our SNP we feel that there is great- er potential for accomplishing them together. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Promontory Point th other names/site number 55 Street Promontory Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 5491 South Shore Drive not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60615 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Historic Preservation Agency State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

2016 Popular Annual Financial Report

CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT Chicago, Illinois Children First Built to Last Best Deal in Town Extra Effort Popular Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2016 Prepared by the Chief Financial Officer and the Office of the Comptroller Rahm Emanuel, Mayor, City of Chicago Jesse H. Ruiz, President of the Board of Commissioners Michael P. Kelly, General Superintendent and Chief Executive Officer Steve Lux, Chief Financial Officer Cecilia Prado, CPA, Comptroller TABLE OF CONTENTS Commissioner’s Letter…………………………………………………………………………………………...….1 Comptroller’s Message……………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Organizational Structure & Management…………...……………………………………………………..3 Map of Parks……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Staffed Locations…………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..5 Operating Indicators………………………………………………………………………………………………....6 CPD Spotlight………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Core Values Children First……………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 Best Deal in Town……………………………………………………..………………………………………..9 Built to Last……………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Extra Effort………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Management’s Discussion & Analysis………………………………………………………………….12-16 Local Economy………………………………………………………………………………………………………...17 Capital Improvement Projects………………………………………………………………………………….18 Community Efforts…………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 Privatized Contracts………………………………………………………………………………………………...20 Featured Parks………………………………………………………………………………....inside back cover Contact Us…………………………………………………………………………………………………..back -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza Lollapalooza returns with four full days in Grant Park August 3-6, 2017. This four-day extravaganza will transform the jewel of Chicago into a mecca of music, food, art, and fashion featuring over 170 bands on eight stages, including Chance The Rapper, The Killers, Muse, Arcade Fire, The xx, Lorde, blink-182, DJ Snake, and Justice, and many more. Lollapalooza will host 100,000 fans each day, and with so much activity, we wanted to provide some top highlights: •SAFETY FIRST: In case of emergency, we urge attendees to be alert to safety messaging coming from the following sources: • Push Notifications through The Official Lollapalooza Mobile App available on Android and iOS • Video Screens at the Main Entrance, North Entrance, and Info Tower by Buckingham Fountain • Video Screens at 4 Stages – Grant Park, Bud Light, Lake Shore and Perry’s • Audio Announcements at All Stages • Real-time updates on Lollapalooza Twitter, Facebook and Instagram In the event of a weather evacuation, all attendees should follow the instructions of public safety officials. Festival patrons can exit the park to the lower level of one of the following shelters: • GRANT PARK NORTH 25 N. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60602 Underground Parking Garage (between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • GRANT PARK SOUTH 325 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 Underground Parking Garage (between Jackson and Van Buren) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • MILLENIUM LAKESIDE 5 S. Columbus Drive Chicago, IL 60603 Underground Parking Garage (Columbus between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan For a map of shelter locations and additional safety information, visit www.lollapalooza.com/safety. -

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center -