Millennium Park Chicago, Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Great Rivers Confidential Draft Draft

greatriverschicago.com OUR GREAT RIVERS CONFIDENTIAL DRAFT DRAFT A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Our Great Rivers: A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers Letter from Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel 4 A report of Great Rivers Chicago, a project of the City of Chicago, Metropolitan Planning Council, Friends of the Chicago River, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and Ross Barney Architects, through generous Letter from the Great Rivers Chicago team 5 support from ArcelorMittal, The Boeing Company, The Chicago Community Trust, The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation and The Joyce Foundation. Executive summary 6 Published August 2016. Printed in Chicago by Mission Press, Inc. The Vision 8 greatriverschicago.com Inviting 11 Productive 29 PARTNERS Living 45 Vision in action 61 CONFIDENTIAL Des Plaines 63 Ashland 65 Collateral Channel 67 Goose Island 69 FUNDERS Riverdale 71 DRAFT DRAFT Moving forward 72 Our Great Rivers 75 Glossary 76 ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT OUR GREAT RIVERS 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This vision and action agenda for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers was produced by the Metropolitan Planning RESOURCE GROUP METROPOLITAN PLANNING Council (MPC), in close partnership with the City of Chicago Office of the Mayor, Friends of the Chicago River and Chicago COUNCIL STAFF Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Margaret Frisbie, Friends of the Chicago River Brad McConnell, Chicago Dept. of Planning and Co-Chair Development Josh Ellis, Director The Great Rivers Chicago Leadership Commission, more than 100 focus groups and an online survey that Friends of the Chicago River brought people to the Aaron Koch, City of Chicago Office of the Mayor Peter Mulvaney, West Monroe Partners appointed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, and a Resource more than 3,800 people responded to. -

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

August Highlights at the Grant Park Music Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jill Hurwitz,312.744.9179 [email protected] AUGUST HIGHLIGHTS AT THE GRANT PARK MUSIC FESTIVAL A world premiere by Aaron Jay Kernis, an evening of mariachi, a night of Spanish guitar and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on closing weekend of the 2017 season CHICAGO (July 19, 2017) — Summer in Chicago wraps up in August with the final weeks of the 83rd season of the Grant Park Music Festival, led by Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Carlos Kalmar with Chorus Director Christopher Bell and the award-winning Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park. Highlights of the season include Legacy, a world premiere commission by the Pulitzer Prize- winning American composer, Aaron Jay Kernis on August 11 and 12, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and acclaimed guest soloists on closing weekend, August 18 and 19. All concerts take place on Wednesday and Friday evenings at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday evenings at 7:30 p.m. (Concerts on August 4 and 5 move indoors to the Harris Theater during Lollapolooza). The August program schedule is below and available at www.gpmf.org. Patrons can order One Night Membership Passes for reserved seats, starting at $25, by calling 312.742.7647 or going online at gpmf.org and selecting their own seat down front in the member section of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Membership support helps to keep the Grant Park Music Festival free for all. For every Festival concert, there are seats that are free and open to the public in Millennium Park’s Seating Bowl and on the Great Lawn, available on a first-come, first-served basis. -

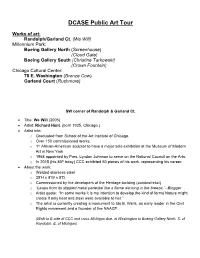

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

Summer 2018 Volume 18 Number 2

PAID Chicago, IL U.S. Postage U.S. Postage Nonprofit Org. Permit No. 9119 TM LIGHTHOUSES Chicago, IL 60608-1288 • ON THE MAG MILE | ENAZ | Highland Park, IL Park, | Highland | ENAZ | Loews Chicago Hotel Chicago | Loews | Chicago’s Magnificent Mile® Magnificent Chicago’s | June 19 - August 11 PRESENTED BY 1850 W. Roosevelt Road Roosevelt 1850 W. UPCOMING EVENTS UPCOMING Mile Mag The on Lighthouses 11 August 19 - June Philanthropy. Fashion. Fun. FLAIR. 2 October Tuesday, Sight for Style 8 November Thursday, Summer 2018 n Volume 18 Number 2 ONCE IN A LIFETIME ART DISPLAY SEEKS TO OPEN DOORS They will steal your hearts THE LIGHTHOUSES SERVE opportunity for people who are and open your eyes to what is blind, visually impaired, disabled Lighthouse are beacons. beacons. are Lighthouse We ask that you become beacons too! beacons become you that ask We David Huber and his firm, Huber Financial Advisors, LLC, as well well as LLC, Advisors, Financial Huber firm, his and Huber David possible. In the process they AS A VIVID REMINDER and Veterans. We all have a role to play. All of us at The Chicago Chicago The at us of All play. to role a have all We with disabilities. with exhibition in partnership with our outstanding Board Member Member Board outstanding our with partnership in exhibition will ask you to become engaged ABOUT WHAT PEOPLE can do to create access and inclusion for our fellow citizens citizens fellow our for inclusion and access create to do can For Dr. Szlyk, the lighthouses The Chicago Lighthouse is very proud to present this world class class world this present to proud very is Lighthouse Chicago The and consider what you can do serve as a vivid reminder about enjoy our lighthouses this summer, ask yourselves, what you you what yourselves, ask summer, this lighthouses our enjoy as an individual to break down WITH DISABILITIES and national artists, including many people who are disabled. -

Culturalupdate

CONCIERGE UNLIMITED INTERNATIONAL July 2016 culturalupdate Volume XXVI—Issue VII “Fireworks and temperatures are exploding!” Did You Know? ♦Independence Day♦Beach Getaways♦Festivals♦and more♦ The Wrigley Building was the first air-conditioned office building in Chicago! New/News Arts/Museums ♦Bad Hunter (802 W. Randolph, Chicago) Opens 2 Witness MCA Chicago Bad Hunter is coming to the West Loop. Slated to 15 Copying Delacroix’s Big Cats Art Institute Chicago open in late summer, Bad Hunter will specialize 15 Post Black Folk Art in America Center for Outsider Art in meats fired up on a wooden grill, along with a 16 The Making of a Fugitive MCA Chicago lower-alcohol cocktail menu. 26 Andrew Yang MCA Chicago ♦The Terrace At Trump (401 N. Wabash, Chicago) Through 3 Materials Inside and Out Art Institute Chicago The Terrace At Trump just completed 3 Diane Simpson MCA Chicago renovations on their rooftop! Enjoy a 10 Eighth BlackBird Residency MCA Chicago signature cocktail with stellar views and 11 The Inspired Chinese Brush Art Institute Chicago walk away impressed! 17 La Paz Hyde Park Art Center 17 Botany of Desire Hyde Park Art Center ♦Rush Hour Concerts at St. James Cathedral (65 E. Huron) 17 Steve Moseley Patience Bottles Center for Outsider Art Forget about sitting in traffic or running to your destination. Enjoy 18 Antiquaries of England Art Institute Chicago FREE rush hour concerts at St. James Cathedral Tuesday’s in July! Ongoing ♦5th: Russian Romantic Arensky Piano Trio No. 1 What is a Planet Adler Planetarium ♦12th: Debroah Sobol -

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 Update II August 18, 2014

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 update II August 18, 2014 Dear Friends, The Streeterville Neighborhood Plan (“SNP”) was originally written in 2005 as a community plan written by a Chicago community group, SOAR, the Streeterville Organization of Active Resi- dents. SOAR was incorporated on May 28, 1975. Throughout our history, the organization has been a strong voice for conserving the historic character of the area and for development that enables divergent interests to live in harmony. SOAR’s mission is “To work on behalf of the residents of Streeterville by preserving, promoting and enhancing the quality of life and community.” SOAR’s vision is to see Streeterville as a unique, vibrant, beautiful neighborhood. In the past decade, since the initial SNP, there has been significant development throughout the neighborhood. Streeterville’s population has grown by 50% along with new hotels, restaurants, entertainment and institutional buildings creating a mix of uses no other neighborhood enjoys. The balance of all these uses is key to keeping the quality of life the highest possible. Each com- ponent is important and none should dominate the others. The impetus to revising the SNP is the City of Chicago’s many new initiatives, ideas and plans that SOAR wanted to incorporate into our planning document. From “The Pedestrian Plan for the City”, to “Chicago Forward”, to “Make Way for People” to “The Redevelopment of Lake Shore Drive” along with others, the City has changed its thinking of the downtown urban envi- ronment. If we support and include many of these plans into our SNP we feel that there is great- er potential for accomplishing them together. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2, 2017 Lollapalooza 2017 Tip Sheet Important Facts & Features of Lollapalooza Lollapalooza returns with four full days in Grant Park August 3-6, 2017. This four-day extravaganza will transform the jewel of Chicago into a mecca of music, food, art, and fashion featuring over 170 bands on eight stages, including Chance The Rapper, The Killers, Muse, Arcade Fire, The xx, Lorde, blink-182, DJ Snake, and Justice, and many more. Lollapalooza will host 100,000 fans each day, and with so much activity, we wanted to provide some top highlights: •SAFETY FIRST: In case of emergency, we urge attendees to be alert to safety messaging coming from the following sources: • Push Notifications through The Official Lollapalooza Mobile App available on Android and iOS • Video Screens at the Main Entrance, North Entrance, and Info Tower by Buckingham Fountain • Video Screens at 4 Stages – Grant Park, Bud Light, Lake Shore and Perry’s • Audio Announcements at All Stages • Real-time updates on Lollapalooza Twitter, Facebook and Instagram In the event of a weather evacuation, all attendees should follow the instructions of public safety officials. Festival patrons can exit the park to the lower level of one of the following shelters: • GRANT PARK NORTH 25 N. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60602 Underground Parking Garage (between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • GRANT PARK SOUTH 325 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 Underground Parking Garage (between Jackson and Van Buren) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan Ave. • MILLENIUM LAKESIDE 5 S. Columbus Drive Chicago, IL 60603 Underground Parking Garage (Columbus between Monroe and Randolph) *Enter via vehicle entrance on Michigan For a map of shelter locations and additional safety information, visit www.lollapalooza.com/safety. -

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015 www.nrpa.org/Innovation-Labs Welcome and Introductions Mike Kelly Superintendent and CEO Chicago Park District Kevin O’Hara NRPA Vice President of Urban and Government Affairs www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Economic Impact of Parks The Chicago Story Antonio Benecchi Principal, Civic Consulting Alliance Chad Coffman President, Global Economics Group www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Impact of the Chicago Park District on Chicago’s Economy NRPA Innovation Lab 30 July 2015 The charge: is there a way to measure the impact of the Park Districts assets? . One of the largest municipal park managers in the country . Financed through taxes and proceeds from licenses, rents etc. Controls over 600 assets, including Parks, beaches, harbors . 11 museums are located on CPD properties . The largest events in the City are hosted by CPD parks 5 Approach summary Relative improvement on Revenues generated by value of properties in parks' events and special assets proximity . Hotel stays, event attendance, . Best indicator of value museum visits, etc. by regarding benefits tourists capture additional associated with Parks' benefit . Proxy for other qualitative . Direct spending by locals factors such as quality of life indicates economic . Higher value of properties in significance driven by the parks' proximity can be parks considered net present . Revenues generated are value of benefit estimated on a yearly basis Property values: tangible benefit for Chicago residents Hypothesis: . Positive benefit of parks should be reflected by value of properties in their proximity . It incorporates other non- tangible aspects like quality of life, etc. -

Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting

FIRST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF RENOIR’S FULL-LENGTH CANVASES BRINGS TOGETHER ICONIC WORKS FROM EUROPE AND THE U.S. FOR AN EXCLUSIVE NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITION RENOIR, IMPRESSIONISM, AND FULL-LENGTH PAINTING February 7 through May 13, 2012 This winter and spring The Frick Collection presents an exhibition of nine iconic Impressionist paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, offering the first comprehensive study of the artist’s engagement with the full-length format. Its use was associated with the official Paris Salon from the mid-1870s to mid- 1880s, the decade that saw the emergence of a fully fledged Impressionist aesthetic. The project was inspired by Renoir’s La Promenade of 1875–76, the most significant Impressionist work in the Frick’s permanent collection. Intended for public display, the vertical grand-scale canvases in the exhibition are among the artist’s most daring and ambitious presentations of contemporary subjects and are today considered masterpieces of Impressionism. The show and accompanying catalogue draw on contemporary criticism, literature, and archival documents to explore the motivation behind Renoir’s full-length figure paintings as well as their reception by critics, peers, and the public. Recently-undertaken technical studies of the canvases will also shed new light on the artist’s working methods. Works on loan from international institutions are La Parisienne from Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Dance at Bougival, 1883, oil on canvas, 71 5/8 x 38 5/8 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Picture Fund; photo: © 2012 Museum the National Museum Wales, Cardiff; The Umbrellas (Les Parapluies) from The of Fine Arts, Boston National Gallery, London (first time since 1886 on view in the United States); and Dance in the City and Dance in the Country from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. -

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago’s Parks by Julia S. Bachrach, Chicago Park District Historian In 1909, Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) and Edward Bennett published the Plan of Chicago, a seminal work that had a major impact, not only on the city of Chicago’s future development, but also to the burgeoning field of urban planning. Today, govern- ment agencies, institutions, universities, non-profit organizations and private firms throughout the region are coming together 100 years later under the auspices of the Burnham Plan Centennial to educate and inspire people throughout the region. Chicago will look to build upon the successes of the Plan and act boldly to shape the future of Chicago and the surrounding areas. Begin- ning in the late 1870s, Burnham began making important contri- butions to Chicago’s parks, and much of his park work served as the genesis of the Plan of Chicago. The following essay provides Daniel Hudson Burnham from a painting a detailed overview of this fascinating topic. by Zorn , 1899, (CM). Early Years Born in Henderson, New York in 1846, Daniel Hudson Burnham moved to Chi- cago with his parents and six siblings in the 1850s. His father, Edwin Burnham, found success in the wholesale drug busi- ness and was appointed presidet of the Chicago Mercantile Association in 1865. After Burnham attended public schools in Chicago, his parents sent him to a college preparatory school in New England. He failed to be accepted by either Harvard or Yale universities, however; and returned Plan for Lake Shore from Chicago Ave. on the north to Jackson Park on the South , 1909, (POC).