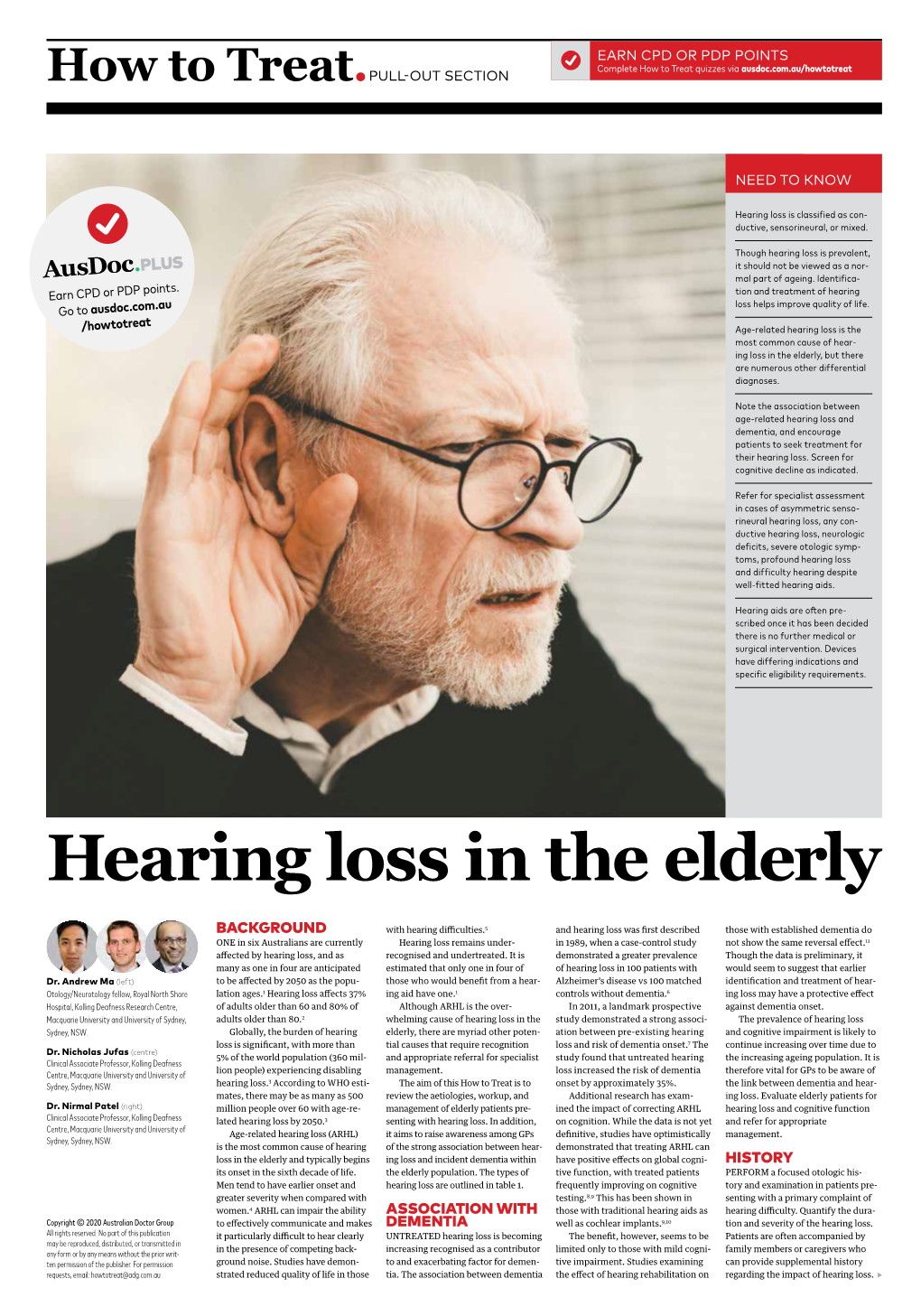

Hearing Loss in the Elderly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: a Clinical Study

Int Adv Otol 2014; 10(2): 102-6 • DOI: 10.5152/iao.2014.40 Original Article A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: A Clinical Study Can Özbay, Rıza Dündar, Erkan Kulduk, Kemal Fatih Soy, Mehmet Aslan, Hüseyin Katılmış Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Şifa University Faculty of Medicine, İzmir, Turkey (CÖ) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Mardin State Hospital, Mardin, Turkey (RD, EK, KFS, MA) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Katip Çelebi University Atatürk Training and Research Hospital, İzmir, Turkey (HK) OBJECTIVE: Myringosclerosis (MS) is a pathological condition characterized by hyaline degeneration and calcification of the collagenous structure of the fibrotic layer of the tympanic membrane, which may develop after trauma, infection, or inflammation as myringotomy, insertion of a ventila- tion tube, or myringoplasty. The aim of our study was to both reveal and evaluate the impact of the factors that might be effective on the post-tym- panoplasty development of myringosclerosis in the graft. MATERIALS and METHODS: In line with this objective, a total of 108 patients (44 males and 64 females) aged between 11 and 66 years (mean age, 29.5 years) who had undergone type 1 tympanoplasty (TP) with an intact canal wall technique and type 2 TP, followed up for an average of 38.8 months, were evaluated. In the presence of myringosclerosis, in consideration of the tympanic membrane (TM) quadrants involved, the influential factors were analyzed in our study, together with the development of myringosclerosis, including preoperative factors, such as the presence of myringosclerosis in the residual and also contralateral tympanic membrane, extent and location of the perforation, and perioperative factors, such as tympanosclerosis in the middle ear and mastoid cavity, cholesteatoma, granulation tissue, and type of the operation performed. -

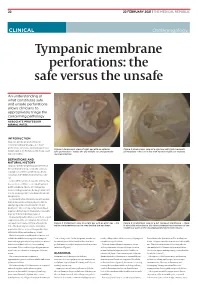

Tympanic Membrane Perforations: the Safe Versus the Unsafe

TMR_210222_22 2021-02-12T14:56:54+11:00 22 22 FEBRUARY 2021 | THE MEDICAL REPUBLIC CLINICAL Otolaryngology Tympanic membrane perforations: the safe versus the unsafe An understanding of what constitutes safe and unsafe perforations allows clinicians to appropriately triage the concerning pathology ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR NIRMAL PATEL INTRODUCTION Tympanic membrane perforations are seen frequently in general practice. Some perforations can be associated with significant Figure 1: Endoscopic view of right ear with an anterior Figure 2: Endoscopic view of a right ear with twin traumatic disease, such as cholesteatoma which may cause safe perforation – notice the dry middle ear and posterior perforations – the ear is dry with normal middle ear mucosa. major morbidity. myringosclerosis DEFINITIONS AND NATURAL HISTORY Tympanic membrane perforations are holes in the ear drum that most commonly occur as a consequence of either ear infections, chronic eustachian tube dysfunction or trauma to the ear. Acute middle ear infection (acute otitis media) is a common condition occurring at least once in 80% of children. Most acute otitis media resolves with spontaneous discharge of infected secretions through the eustachian tube into the nasopharynx. Occasionally when the infections are frequent, there is extensive scarring (tympanosclerosis and myringosclerosis) of the ear drum and middle ear . This scarring compromises blood supply to the healing ear drum and occasionally stops the hole from healing. (Figure 1) Traumatically induced holes occur from a rapid compression of the air column in the external ear canal, most commonly from a blow to the Figure 3: Endoscopic view of a right ear with an attic wax – the Figure 4: Endoscopic view of a left tympanic membrane – there white cholesteatoma can be seen behind the ear drum. -

NOISE and MILITARY SERVICE Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus

NOISE AND MILITARY SERVICE Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Committee on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Associated with Military Service from World War II to the Present Medical Follow-up Agency Larry E. Humes, Lois M. Joellenbeck, and Jane S. Durch, Editors THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, DC www.nap.edu THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS • 500 Fifth Street, N.W. • Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Insti- tute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study was supported by Contract No. V101(93)P-1637 #29 between the Na- tional Academy of Sciences and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Any opinions, find- ings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the organizations or agencies that provided support for this project. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Noise and military service : implications for hearing loss and tinnitus / Committee on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Associated with Military Service from World War II to the Present, Medical Follow- up Agency ; Larry E. Humes, Lois M. Joellenbeck, and Jane S. Durch, editors. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-309-09949-8 — ISBN 0-309-65307-X 1. Deafness—Etiology. -

Migraine Associated Vertigo

Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain VC 2015 American Headache Society Published by JohnWiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1111/head.12704 Headache Toolbox Migraine Associated Vertigo Between 30 and 50% of migraineurs will sometimes times a condition similar to benign positional vertigo experience dizziness, a sense of spinning, or feeling like called vestibular neuronitis (or vestibular neuritis/labyrinthi- their balance is off in the midst of their headaches. This is tis) is triggered by a viral infection of the inner ear, result- now termed vestibular migraine, but is also called ing in constant vertigo or unsteadiness. Symptoms can migraine associated vertigo. Sometimes migraineurs last for a few days to a few weeks and then go away as experience these symptoms before the headache, but mysteriously as they came on. Vestibular migraine, by they can occur during the headache, or even without any definition, should have migraine symptoms in at least head pain. In children, vertigo may be a precursor to 50% of the vertigo episodes, and these include head migraines developing in the teens or adulthood. Migraine pain, light and noise sensitivity, and nausea. associated vertigo may be more common in those with There are red flags, which are warning signs that ver- motion sickness. tigo is not part of a migraine. Sudden hearing loss can be For some patients this vertiginous sensation resem- the sign of an infection that needs treatment. Loss of bal- bles migraine aura, which is a reversible, relatively short- ance alone, or accompanied by weakness can be the lived neurologic symptom associated with their migraines. -

Instruction Sheet: Otitis Externa

University of North Carolina Wilmington Abrons Student Health Center INSTRUCTION SHEET: OTITIS EXTERNA The Student Health Provider has diagnosed otitis externa, also known as external ear infection, or swimmer's ear. Otitis externa is a bacterial/fungal infection in the ear canal (the ear canal goes from the outside opening of the ear to the eardrum). Water in the ear, from swimming or bathing, makes the ear canal prone to infection. Hot and humid weather also predisposes to infection. Symptoms of otitis externa include: ear pain, fullness or itching in the ear, ear drainage, and temporary loss of hearing. These symptoms are similar to those caused by otitis media (middle ear infection). To differentiate between external ear infection and middle ear infection, the provider looks in the ear with an instrument called an otoscope. It is important to distinguish between the two infections, as they are treated differently: External otitis is treated with drops in the ear canal, while middle ear infection is sometimes treated with an antibiotic by mouth. MEASURES YOU SHOULD TAKE TO HELP TREAT EXTERNAL EAR INFECTION: 1. Use the ear drops regularly, as directed on the prescription. 2. The key to treatment is getting the drops down into the canal and keeping the medicine there. To accomplish this: Lie on your side, with the unaffected ear down. Put three to four drops in the infected ear canal, then gently pull the outer ear back and forth several times, working the medicine deeper into the ear canal. Remain still, good-ear-side-down for about 15 minutes. -

BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Biomed Central

BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders BioMed Central Case report Open Access Acute unilateral hearing loss as an unusual presentation of cholesteatoma Daniel Thio*1, Shahzada K Ahmed2 and Richard C Bickerton3 Address: 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, South Warwickshire General Hospitals NHS Trust Warwick CV34 5BW UK, 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, South Warwickshire General Hospitals NHS Trust Warwick CV34 5BW UK and 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology, South Warwickshire General Hospitals NHS Trust Warwick CV34 5BW UK Email: Daniel Thio* - [email protected]; Shahzada K Ahmed - [email protected]; Richard C Bickerton - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 18 September 2005 Received: 10 July 2005 Accepted: 18 September 2005 BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2005, 5:9 doi:10.1186/1472-6815-5-9 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/5/9 © 2005 Thio et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Cholesteatomas are epithelial cysts that contain desquamated keratin. Patients commonly present with progressive hearing loss and a chronically discharging ear. We report an unusual presentation of the disease with an acute hearing loss suffered immediately after prolonged use of a pneumatic drill. Case presentation: A 41 year old man with no previous history of ear problems presented with a sudden loss of hearing in his right ear immediately following the prolonged use of a pneumatic drill on concrete. -

Deafness and Hearing Loss Caroline’S Story

Deafness and Hearing Loss Caroline’s Story Caroline is six years old, A publication of NICHCY with bright brown eyes and, at Disability Fact Sheet #3 June 2010 the moment, no front teeth, like so many other first graders. She also wears a hearing aid in each ear—and has done so since she was three, when she Caroline was immediately Hearing Loss was diagnosed with a moderate fitted with hearing aids. She in Children hearing loss. also began receiving special education and related services Hearing is one of our five For Caroline’s parents, there through the public school senses. Hearing gives us access were many clues along the way. system. Now in the first grade, to sounds in the world around Caroline often didn’t respond she regularly gets speech us—people’s voices, their to her name if her back was therapy and other services, and words, a car horn blown in turned. She didn’t startle at her speech has improved warning or as hello! noises that made other people dramatically. So has her vocabu- jump. She liked the TV on loud. lary and her attentiveness. She When a child has a hearing But it was the preschool she sits in the front row in class, an loss, it is cause for immediate started attending when she was accommodation that helps her attention. That’s because three that first put the clues hear the teacher clearly. She’s language and communication together and suggested to back on track, soaking up new skills develop most rapidly in Caroline’s parents that they information like a sponge, and childhood, especially before the have her hearing checked. -

Cholesteatoma Handout

Cholesteatoma Handout A cholesteatoma is a skin growth that occurs in an abnormal location, usually in the middle ear space behind the eardrum. It often arises from repeated or chronic infection, which causes an in-growth of the skin of the eardrum. Cholesteatomas often take the form of a cyst or pouch that sheds layers of old skin that build up inside the ear. Over time, the cholesteatoma can increase in size and destroy the surrounding delicate bones of the middle ear. Hearing loss, dizziness, and facial muscle paralysis are rare but can result from continued cholesteatoma growth. What are the symptoms? Initially, the ear may drain fluid, sometimes with a foul odor. As the cholesteatoma pouch or sac enlarges, it can cause a full feeling or pressure in the ear, along with hearing loss. Dizziness, or muscle weakness on one side of the face can also occur. Is it dangerous? Ear cholesteatomas can be dangerous and should never be ignored. Bone erosion can cause the infection to spread into the surrounding areas, including the inner ear and brain. If untreated, deafness, brain abscess, meningitis, and rarely death can occur. What treatment can be provided? Initial treatment may consist of a careful cleaning of the ear, antibiotics, and ear drops. Therapy aims to stop drainage in the ear by controlling the infection. The extent or growth characteristics of a cholesteatoma must then be evaluated. Cholesteatomas usually require surgical treatment to protect the patient from serious complications. Hearing and balance tests and CT scans of the ear may be necessary. These tests are performed to determine the hearing level remaining in the ear and the extent of destruction the cholesteatoma has caused. -

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Vestibular Neuritis and DISORDERS Labyrinthitis: Infections of the Inner Ear By Charlotte L. Shupert, PhD with contributions from Bridget Kulick, PT and the Vestibular Disorders Association INFECTIONS Result in damage to inner ear and/or nerve. ARTICLE 079 DID THIS ARTICLE HELP YOU? SUPPORT VEDA @ VESTIBULAR.ORG Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are disorders resulting from an 5018 NE 15th Ave. infection that inflames the inner ear or the nerves connecting the inner Portland, OR 97211 ear to the brain. This inflammation disrupts the transmission of sensory 1-800-837-8428 information from the ear to the brain. Vertigo, dizziness, and difficulties [email protected] with balance, vision, or hearing may result. vestibular.org Infections of the inner ear are usually viral; less commonly, the cause is bacterial. Such inner ear infections are not the same as middle ear infections, which are the type of bacterial infections common in childhood affecting the area around the eardrum. VESTIBULAR.ORG :: 079 / DISORDERS 1 INNER EAR STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION The inner ear consists of a system of fluid-filled DEFINITIONS tubes and sacs called the labyrinth. The labyrinth serves two functions: hearing and balance. Neuritis Inflamation of the nerve. The hearing function involves the cochlea, a snail- shaped tube filled with fluid and sensitive nerve Labyrinthitis Inflamation of the labyrinth. endings that transmit sound signals to the brain. Bacterial infection where The balance function involves the vestibular bacteria infect the middle organs. Fluid and hair cells in the three loop-shaped ear or the bone surrounding semicircular canals and the sac-shaped utricle and Serous the inner ear produce toxins saccule provide the brain with information about Labyrinthitis that invade the inner ear via head movement. -

Vestibular Neuritis, Labyrinthitis, and a Few Comments Regarding Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Marcello Cherchi

Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and a few comments regarding sudden sensorineural hearing loss Marcello Cherchi §1: What are these diseases, how are they related, and what is their cause? §1.1: What is vestibular neuritis? Vestibular neuritis, also called vestibular neuronitis, was originally described by Margaret Ruth Dix and Charles Skinner Hallpike in 1952 (Dix and Hallpike 1952). It is currently suspected to be an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to the balance-related nerve (vestibular nerve) between the ear and the brain that manifests with abrupt-onset, severe dizziness that lasts days to weeks, and occasionally recurs. Although vestibular neuritis is usually regarded as a process affecting the vestibular nerve itself, damage restricted to the vestibule (balance components of the inner ear) would manifest clinically in a similar way, and might be termed “vestibulitis,” although that term is seldom applied (Izraeli, Rachmel et al. 1989). Thus, distinguishing between “vestibular neuritis” (inflammation of the vestibular nerve) and “vestibulitis” (inflammation of the balance-related components of the inner ear) would be difficult. §1.2: What is labyrinthitis? Labyrinthitis is currently suspected to be due to an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to both the “hearing component” (the cochlea) and the “balance component” (the semicircular canals and otolith organs) of the inner ear (labyrinth) itself. Labyrinthitis is sometimes also termed “vertigo with sudden hearing loss” (Pogson, Taylor et al. 2016, Kim, Choi et al. 2018) – and we will discuss sudden hearing loss further in a moment. Labyrinthitis usually manifests with severe dizziness (similar to vestibular neuritis) accompanied by ear symptoms on one side (typically hearing loss and tinnitus). -

ICD-9 Diseases of the Ear and Mastoid Process 380-389

DISEASES OF THE EAR AND MASTOID PROCESS (380-389) 380 Disorders of external ear 380.0 Perichondritis of pinna Perichondritis of auricle 380.00 Perichondritis of pinna, unspecified 380.01 Acute perichondritis of pinna 380.02 Chronic perichondritis of pinna 380.1 Infective otitis externa 380.10 Infective otitis externa, unspecified Otitis externa (acute): NOS circumscribed diffuse hemorrhagica infective NOS 380.11 Acute infection of pinna Excludes: furuncular otitis externa (680.0) 380.12 Acute swimmers' ear Beach ear Tank ear 380.13 Other acute infections of external ear Code first underlying disease, as: erysipelas (035) impetigo (684) seborrheic dermatitis (690.10-690.18) Excludes: herpes simplex (054.73) herpes zoster (053.71) 380.14 Malignant otitis externa 380.15 Chronic mycotic otitis externa Code first underlying disease, as: aspergillosis (117.3) otomycosis NOS (111.9) Excludes: candidal otitis externa (112.82) 380.16 Other chronic infective otitis externa Chronic infective otitis externa NOS 380.2 Other otitis externa 380.21 Cholesteatoma of external ear Keratosis obturans of external ear (canal) Excludes: cholesteatoma NOS (385.30-385.35) postmastoidectomy (383.32) 380.22 Other acute otitis externa Excerpted from “Dtab04.RTF” downloaded from website regarding ICD-9-CM 1 of 11 Acute otitis externa: actinic chemical contact eczematoid reactive 380.23 Other chronic otitis externa Chronic otitis externa NOS 380.3 Noninfectious disorders of pinna 380.30 Disorder of pinna, unspecified 380.31 Hematoma of auricle or pinna 380.32 Acquired -

Bedside Neuro-Otological Examination and Interpretation of Commonly

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054478 on 24 November 2004. Downloaded from BEDSIDE NEURO-OTOLOGICAL EXAMINATION AND INTERPRETATION iv32 OF COMMONLY USED INVESTIGATIONS RDavies J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75(Suppl IV):iv32–iv44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054478 he assessment of the patient with a neuro-otological problem is not a complex task if approached in a logical manner. It is best addressed by taking a comprehensive history, by a Tphysical examination that is directed towards detecting abnormalities of eye movements and abnormalities of gait, and also towards identifying any associated otological or neurological problems. This examination needs to be mindful of the factors that can compromise the value of the signs elicited, and the range of investigative techniques available. The majority of patients that present with neuro-otological symptoms do not have a space occupying lesion and the over reliance on imaging techniques is likely to miss more common conditions, such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), or the failure to compensate following an acute unilateral labyrinthine event. The role of the neuro-otologist is to identify the site of the lesion, gather information that may lead to an aetiological diagnosis, and from there, to formulate a management plan. c BACKGROUND Balance is maintained through the integration at the brainstem level of information from the vestibular end organs, and the visual and proprioceptive sensory modalities. This processing takes place in the vestibular nuclei, with modulating influences from higher centres including the cerebellum, the extrapyramidal system, the cerebral cortex, and the contiguous reticular formation (fig 1).