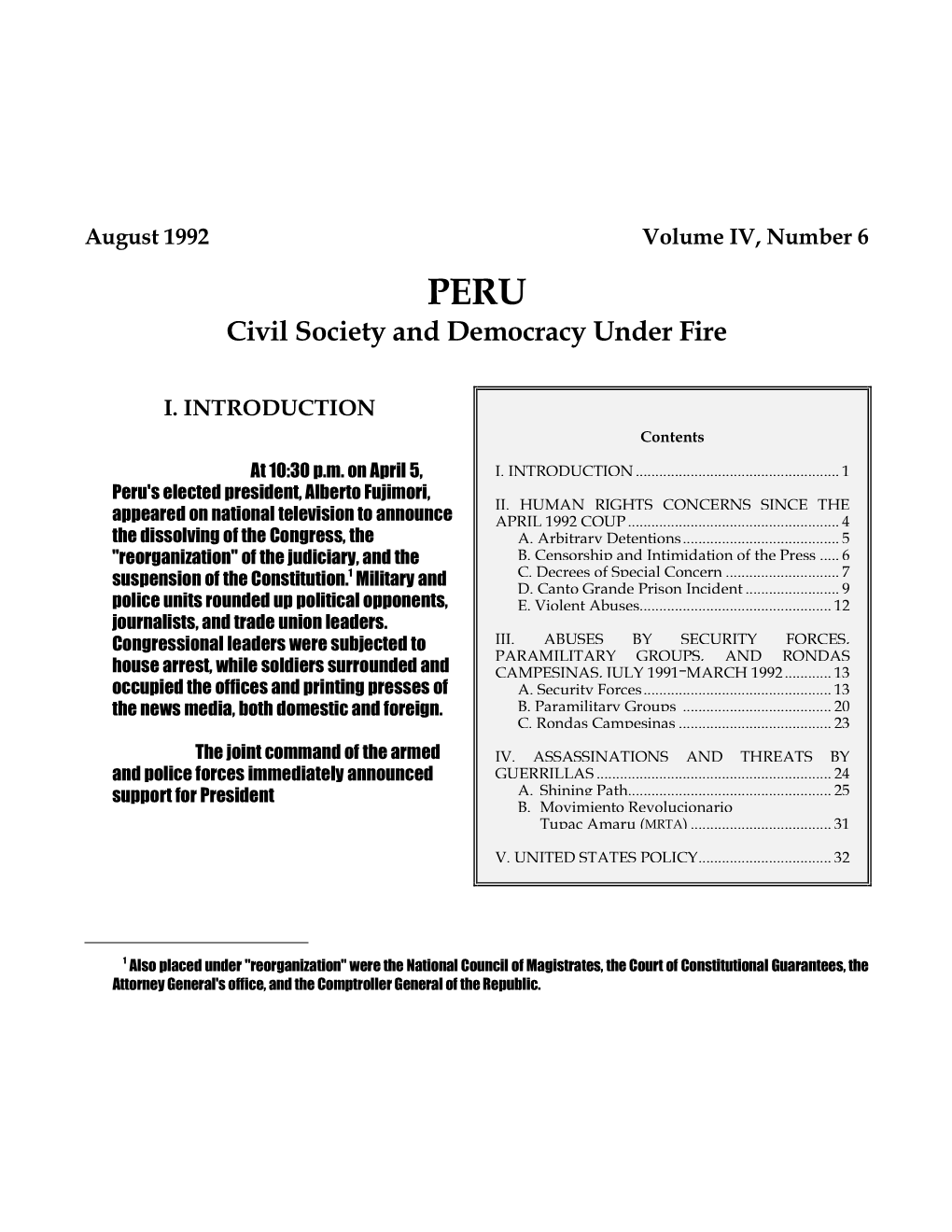

Civil Society and Democracy Under Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HM 342 the Trial of Alberto Fujimori

The trial of Alberto Fujimori by Jo-Marie Burt* Jo-Marie Burt witnessed the first week of former President Alberto Fujimori’s trial in Lima as an accredited observer for WOLA. Here is her report. The trial of Alberto Fujimori started on December 10, 2007, which was also the 59th anniversary of the signing of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Whether he was aware of this irony or not (and he presumably wasn’t; human rights law is not exactly his forte), Fujimori stands accused of precisely the sorts of crimes that the magna carta of human rights protection was meant to prevent: ordering abductions and extra-judicial killings and abuse of authority during his rule from 1990 to 2000. The “mega-trial,” as Peruvians call of it, of their former president is currently limited to charges for which Fujimori was extradited to Peru from Chile in September. These include human rights violations in three cases: the Barrios Altos massacre of 1991, in which 15 people were killed; the disappearance and later killing of nine students and a professor from the Cantuta University in 1992; and the kidnapping of journalist Gustavo Gorriti and businessman Samuel Dyer in the aftermath of the April 5, 1992, coup d’état in which Fujimori closed Congress, suspended the Constitution, and took control over the judiciary with the backing of the armed forces. Fujimori is also charged, in other legal proceedings, with corruption and abuse of authority in four cases, including phone tapping of the opposition; bribing members of Congress; embezzlement of state funds for illegal purposes; and the transfer of $15 million in public funds to Vladimiro Montesinos, de facto head of the National Intelligence Service (SIN). -

Infected Areas As on 26 January 1989 — Zones Infectées an 26 Janvier 1989 for Criteria Used in Compiling This List, See No

Wkty Epidem Rec No 4 - 27 January 1989 - 26 - Relevé éptdém hebd . N°4 - 27 janvier 1989 (Continued from page 23) (Suite de la page 23) YELLOW FEVER FIÈVRE JAUNE T r in id a d a n d T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — Further to the T r i n i t é - e t -T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — A la suite du rapport report of yellow fever virus isolation from mosquitos,* 1 the Min concernant l’isolement du virus de la fièvre jaune sur des moustiques,1 le istry of Health advises that there are no human cases and that the Ministère de la Santé fait connaître qu’il n’y a pas de cas humains et que risk to persons in urban areas is epidemiologically minimal at this le risque couru par des personnes habitant en zone urbaine est actuel time. lement minime. Vaccination Vaccination A valid certificate of yellow fever vaccination is N O T required Il n’est PAS exigé de certificat de vaccination anuamarile pour l’en for entry into Trinidad and Tobago except for persons arriving trée à la Trinité-et-Tobago, sauf lorsque le voyageur vient d’une zone from infected areas. (This is a standing position which has infectée. (C’est là une politique permanente qui n ’a pas varié depuis remained unchanged over the last S years.) Sans.) On the other hand, vaccination against yellow fever is recom D’autre part, la vaccination antiamarile est recommandée aux per mended for those persons coming to Trinidad and Tobago who sonnes qui, arrivant à la Trinité-et-Tobago, risquent de se rendre dans may enter forested areas during their stay ; who may be required des zones de -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Community Focused Integration & Protected

COMMUNITY FOCUSED INTEGRATION & PROTECTED AREAS MANAGEMENT IN THE HUASCARÁN BIOSPHERE RESERVE, PERÚ October 2015 | Jessica Gilbert In Summer 2015, ConDev Student Media Grant winner Jessica Gilbert conducted a photojournalism and film project to document land use issues and a variety of stakeholder perspectives in protected areas in Peru. Peru’s natural protected areas are threatened by a host of anthropogenic activities, which lead to additional conflicts with nearby communities. The core of this project involved a trip to Peru in May 2015 to highlight land use challenges in two distinct protected areas: Huascarán National Park and Tambopata National Reserve. In this contribution to the Applied Biodiversity Science Perspectives Series (http://biodiversity.tamu.edu/communications/perspectives-series/), Gilbert discusses the integration of communities into conservation management and criticizes the traditional “fortress”-style conservation policies, which she argues are incompatible with ecosystem conservation. Jessica Gilbert is a Ph.D. student in Texas A&M The Center on Conflict and Development University’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (ConDev) at Texas A&M University seeks to improve Sciences as well as a member of the NSF-IGERT the effectiveness of development programs and policies Applied Biodiversity Sciences Program. for conflict-affected and fragile countries through multidisciplinary research, education and development extension. The Center uses science and technology to reduce armed conflict, sustain families and communities during conflict, and assist states to rapidly recover from conflict. ConDev’s Student Media Grant, funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, awards students with up to $5,000 to chronicle issues facing fragile and conflict- affected nations through innovative media. -

Transitional Justice in the Aftermath of Civil Conflict

Transitional Justice in the Aftermath of Civil Conflict Lessons from Peru, Guatemala and El Salvador Author Jo-Marie Burt Transitional Justice in the Aftermath of Civil Conflict: Lessons from Peru, Guatemala and El Salvador Author Jo-Marie Burt 1779 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 710 Washington, D.C. 20036 T: (202) 462 7701 | F: (202) 462 7703 www.dplf.org 2018 Due Process of Law Foundation All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by Due Process of Law Foundation Washington D.C., 20036 www.dplf.org ISBN: 978-0-9912414-6-0 Cover design: ULTRAdesigns Cover photos: José Ángel Mejía, Salvadoran journalist; Jo-Marie Burt; DPLF Graphic design: ULTRAdesigns Author Acknowledgements iii Author Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the generosity of so many friends, colleagues and collaborators whose insights were critical to the preparation of this report. The experience of writing this report helped reinforce my belief that the theory of transitional justice much emanate from, and constantly be nourished from the experiences of those who engage in its day-to-day work: the survivors, the families of victims, the human rights defenders, lawyers, judicial operators, whose labor creates the things we understand to be transitional justice. My first debt of gratitude is to Katya Salazar, Executive Director of the Due Process of Law Foundation (DPLF), and Leonor Arteaga, Impunity and Grave Human Rights Senior Program Officer at DPLF, for their invitation to collaborate in the preparation of a grant proposal to the Bureau of Democracy, Labor and Human Rights, which led to the two-year funded project on transitional justice in post-conflict Peru, Guatemala and El Salvador that is the basis for this report. -

Diversionary Threats in Latin America: When and Why Do Governments Use the Threat of Foreign Invasion, Intervention, Or Terrorist Attack?

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2019-12 DIVERSIONARY THREATS IN LATIN AMERICA: WHEN AND WHY DO GOVERNMENTS USE THE THREAT OF FOREIGN INVASION, INTERVENTION, OR TERRORIST ATTACK? Searcy, Mason Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/64063 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS DIVERSIONARY THREATS IN LATIN AMERICA: WHEN AND WHY DO GOVERNMENTS USE THE THREAT OF FOREIGN INVASION, INTERVENTION, OR TERRORIST ATTACK? by Mason Searcy December 2019 Thesis Advisor: Cristiana Matei Second Reader: Tristan J. Mabry Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved OMB REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2019 Master's thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS DIVERSIONARY THREATS IN LATIN AMERICA: WHEN AND WHY DO GOVERNMENTS USE THE THREAT OF FOREIGN INVASION, INTERVENTION, OR TERRORIST ATTACK? 6. -

Useful Information for Your Trip to Peru

Welcome to Useful information for your trip to Peru. General Information of Peru The Republic of Peru is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean. The Peruvian population, estimated at 30 million. The main spoken language is Spanish, although a significant number of Peruvians speak Quechua or other native languages like a Aymara, Ashaninka, and others. This mixture of cultural traditions has resulted in a wide diversity of expressions in fields such as art, cuisine, literature, and music. LIMA Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central coastal part of the country, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a continuous urban area known as the Lima Metropolitan Area. With a population approaching 10 million, one third of the whole Peruvian Population, Lima is the most populous metropolitan area of Peru, and the third largest city in the Americas . Capital: Lima City The department of Lima is located in the central occidental part of the country. To the west, it is bathed by the waters of the Pacific Ocean, to the east, it limits with the Andes. It has an extension of 33,820 km² (13,058 sq ml) and a population of over 10'000,000 people. Location: On the west central coast of Peru, on the shores of the Pacific Ocean. -

Tarma Rutas Cortas Desde Lima

César A. Vega/Inkafotos Rutas cortas desde Lima Tarma Tarma Ubicación, distancia, altitud y clima 230 km al noreste de Lima 5 hrs 3050 msnm Antonio Raimondi la bautizó como “La Perla de los max 24°C min 4°C Andes”. Sus tierras acogieron a los hijos de la cultura dic - mar mar - junjun-sep sep - dic Tarama, una de las más importantes de la región central del país, quienes nos dejaron un legado arqueológico de cerca de 500 recintos, entre los que sobresale el Vías de acceso centro administrativo de Tarmatambo. La zona, de Si partes desde Lima, debes tomar la Carretera Central, bellos paisajes, está rodeada de grandes grutas y pasas por Chosica (km 34), Matucana (km 75), San Mateo de lagunas altoandinas, especialmente en el distrito Huanchor (km 93), Ticlio (km 131) hasta llegar a La Oroya de Huasahuasi. Pero eso no es todo, esta es también (km 175) donde la Carretera Central se bifurca en dos grandes tierra de reconocidos artesanos, y su celebración de la caminos: - Si sigues el camino de la izquierda (Norte), llegas a Tarma, Semana Santa traspasa fronteras. Junín, Cerro de Pasco, Huánuco y Pucallpa. César A. Vega/Inkafotos Acceso: Tomar la Panamericana Norte. En el trayecto se pasa por el desvío a Ancón (Km 45). Luego se tiene que cruzar la variante de Pasamayo (tránsito liviano), o el serpentín (tránsito pesado). En el viaje de Lima a Huaral se encontrará un peaje (Km 48). Tener en cuenta que en el tramo de Pasamayo no existen grifos. - Si vas por el camino de la derecha (Sur), llegas al Valle del Mantaro (Jauja, Concepción, Chupaca y Huancayo), Huancavelica y Ayacucho. -

Agricultural and Mining Labor Interactions in Peru: a Long-Run Perspective

Agricultural and Mining Labor Interactions in Peru: ALong-RunPerspective(1571-1812) Apsara Iyer1 April 4, 2016 1Submitted for consideration of B.A. Economics and Mathematics, Yale College Class of 2016. Advisor: Christopher Udry Abstract This essay evaluates the context and persistence of extractive colonial policies in Peru on contemporary development indicators and political attitudes. Using the 1571 Toledan Reforms—which implemented a system of draft labor and reg- ularized tribute collection—as a point of departure, I build a unique dataset of annual tribute records for 160 districts in the Cuzco, Huamanga, Huancavelica, and Castrovirreyna regions of Peru over the years of 1571 to 1812. Pairing this source with detailed historic micro data on population, wages, and regional agri- cultural prices, I develop a historic model for the annual province-level output. The model’s key parameters determine the output elasticities of labor and capital and pre-tribute production. This approach allows for an conceptual understand- ing of the interaction between mita assignment and production factors over time. Ithenevaluatecontemporaryoutcomesofagriculturalproductionandpolitical participation in the same Peruvian provinces, based on whether or not a province was assigned to the mita. I find that assigning districts to the mita lowers the average amount of land cultivated, per capita earnings, and trust in municipal government Introduction For nearly 250 years, the Peruvian economy was governed by a rigid system of state tribute collection and forced labor. Though the interaction between historical ex- traction and economic development has been studied in a variety of post-colonial contexts, Peru’s case is unique due to the distinct administration of these tribute and labor laws. -

World Bank Document

OFFICIAL USE ONLY R2006-0216/1 November 28, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Streamlined Procedure For meeting of Board: Tuesday, December 19, 2006 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Peru - Decentralized Rural Transport Project Project Appraisal Document Public Disclosure Authorized Attached is the Project Appraisal Document regarding a proposed loan to the Republic of Peru for a Decentralized Rural Transport Project (R2006-0216). This project will be taken up at a meeting of the Executive Directors on Tuesday, December 19, 2006 under the Streamlined Procedure. Distribution: Executive Directors and Alternates President Bank Group Senior Management Vice Presidents, Bank, IFC and MIGA Directors and Department Heads, Bank, IFC and MIGA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank Group authorization. Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: 36484-PE PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$50 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF PERU FOR A DECENTRALIZED RURAL TRANSPORT PROJECT November 15, 2006 Finance, Private Sector Development and Infrastructure Department Bolivia, Ecuador, Perú, República Bolivariana de Venezuela Country Management Unit Latin America and the Caribbean Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. -

REPORT Nº 12/93 CASE 10.531 PERU Marzo 12, 1993

REPORT Nº 12/93 CASE 10.531 PERU Marzo 12, 1993 BACKGROUND: 1. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights received a petition dated March 21, 1990, according to which: By means of this letter, we request your urgent intervention with the authorities of our country in behalf of citizen Simerman Rafael Antonio Navarro, identified by electoral passbook number 20006474, 21 years of age, an economics student at the Universidad Nacional del Centro and a student of law and political science at the Andes Private University and formerly a corporal in the Peruvian army, based on the following alleged events: 1. On March 7, 1990, at approximately 10:30 p.m., 12 uniformed members of the Peruvian army, arrived at the residence of the aforementioned person, located some 150 meters from the 9 de Diciembre Barracks, in a white closed pickup truck, with red stripes, located at Pasaje Union No. 105, Chilca district, Huancayo province, Junin department, headquarters of the military political command of the Central National Security Subzone. 2. After breaking down the door of the residence, they went into the room of Simerman Antonio and took him forcibly to the vehicle which was parked some 30 meters from the house. Despite the requests of his parents, he was put into the pickup truck and taken in the direction of the 9 de Diciembre Barracks. 3. A few minutes later, his parents arrived at the barracks with clothing for their son since he had been carried away in his underwear, but once at the military base, they denied that such an operation had taken place. -

WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD RELEVE EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE 15 SEPTEMBER 1995 ● 70Th YEAR 70E ANNÉE ● 15 SEPTEMBRE 1995

WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD, No. 37, 15 SEPTEMBER 1995 • RELEVÉ ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE, No 37, 15 SEPTEMBRE 1995 1995, 70, 261-268 No. 37 World Health Organization, Geneva Organisation mondiale de la Santé, Genève WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD RELEVE EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE 15 SEPTEMBER 1995 c 70th YEAR 70e ANNÉE c 15 SEPTEMBRE 1995 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE Expanded Programme on Immunization – Programme élargi de vaccination – Lot Quality Assurance Evaluation de la couverture vaccinale par la méthode dite de Lot survey to assess immunization coverage, Quality Assurance (échantillonnage par lots pour l'assurance de la qualité), Burkina Faso 261 Burkina Faso 261 Human rabies in the Americas 264 La rage humaine dans les Amériques 264 Influenza 266 Grippe 266 List of infected areas 266 Liste des zones infectées 266 Diseases subject to the Regulations 268 Maladies soumises au Règlement 268 Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) Programme élargi de vaccination (PEV) Lot Quality Assurance survey to assess immunization coverage Evaluation de la couverture vaccinale par la méthode dite de Lot Quality Assurance (échantillonnage par lots pour l'assurance de la qualité) Burkina Faso. In January 1994, national and provincial Burkina Faso. En janvier 1994, les autorités nationales et provin- public health authorities, in collaboration with WHO, con- ciales de santé publique, en collaboration avec l’OMS, ont mené ducted a field survey to evaluate immunization coverage une étude sur le terrain pour évaluer la couverture vaccinale des for children 12-23 months of age in the city of Bobo enfants de 12 à 23 mois dans la ville de Bobo Dioulasso. L’étude a Dioulasso. The survey was carried out using the method of utilisé la méthode dite de Lot Quality Assurance (LQA) plutôt que Lot Quality Assurance (LQA) rather than the 30-cluster la méthode des 30 grappes plus couramment utilisée par les pro- survey method which has traditionally been used by immu- grammes de vaccination.