Ethnographic Series Gujara, Scheduled Caste of Gujarat, Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rajputs: a Fighting Race

JHR1 JEvSSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA MLJ^.A.S. GIFT OF HORACE W. CARPENTER THE RAJPUTS: A FIGHTING RACE THEIR IMPERIAL MAJESTIES KING-EMPEROR GEORGE V. AND QUEEN-EMPRESS MARY OF INDIA KHARATA KE SAMRAT SRT PANCHME JARJ AI.4ftF.SH. SARVE BHAUMA KK RAJAHO JKVOH LAKH VARESH. Photographs by IV. &* D, Downey, London, S.W. ITS A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE , RAJPUT. ,RAC^ WARLIKE PAST, ITS EARLY CONNEC^tofe WITH., GREAT BRITAIN, AND ITS GALLANT SERVICES AT THE PRESENT MOMENT AT THE FRONT BY THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA " M.R.A.S. BEAUTIFULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS A FOREWORD BY GENERAL SIR O'MOORE CREAGH V.C., G.C.B., G.C.S.I. EX-COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF, INDIA LONDON EAST AND WEST, LTD. 3, VICTORIA STREET, S.W. 1915 H.H. RANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR, OF BARWANI THE RAJA OF BARWANI TO HIS HIGHNESS MAHARANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR MAHARAJA OF BARWANI AS A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT FOR YOUR HIGHNESS'S MANY ADMIRABLE QUALITIES THIS HUMBLE EFFORT HAS BEEN WITH KIND PERMISSION Dedicates BY YOUR HIGHNESS'S MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT AND CLANSMAN JESSRAJSINGH SEESODIA 440872 FOREWORD THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJ SINGHJI has asked me, as one who has passed most of his life in India, to write a Foreword to this little book to speed it on its way. The object the Thakur Sahib has in writing it is to benefit the fund for the widows and orphans of those Indian soldiers killed in the present war. To this fund he intends to give 50 per cent, of any profits that may accrue from its sale. -

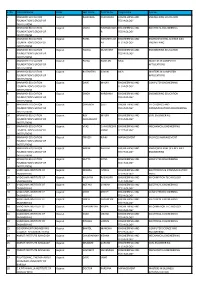

Sl. No Name of the Beneficiary Parent Name Age Gender Caste Address 1 Megh Patel Hitesh Kumar 10Yrs Male G

Sl. No Name of the Beneficiary Parent Name Age Gender Caste Address 1 Megh Patel Hitesh Kumar 10Yrs Male G. Parnashil Residency Bwehind Krishna Park Ajwa Waghod Ring Road, Vadodara. 2 Mital Ben Vinod Bhai 11Yrs Female 69-Janka Nagar, Society Mothers School Road, Near Jailar Malenagar. 3 Nisargohil Alpesh Singh 7Yrs Male C-15, Kiritmandir, Staff Quarters, Near Aaradana Cinema, Saltwada, Vadodara. 4 Manav Patel Vasanth Bhai 11Yrs Male Sri Malenagar, Ambika Nagar, Pachal Svvast, Vododara 5 Devparte Dinesh Bhai 7Yrs Male 1-Tej Quarters Behind Urmi Apartment, Fateachgunj, Vadodara 6 Deepiika Pagare Kishore 7Yrs Female Gokul Nagar, Gotri Road. 7 Vrushika Patel Vishnu Bhai 10 Yrs Female Parot Faliyu-1Vadsar, Gam, Vadodara Mandal 8 Faiza Patel Ismail 9Yrs Female 3-17, Madura Ramalesociety Near Jp Poloce Station, Tandaza. 9 Priyansh Patel Mayanek Patel 10 Yrs Male A-7-Shanti Kunj Soc Opp Raj Nagar Arunachal Samia Road, Vadodara 10 Dakshparekam Umesh Bhai 10Yrs Male Plot-83, Eev Nagar, 2 Old Pared Road, Biwualipura 11 Rana Harsh Kiran Kumar 11Yrs Male C-21, Saurabhtenament,Nrch Vidiyilaya 12 Nishth Shah Arvinod Bhai 25Yrs Male 27, Divyak Society, Mala Pur Vadodara. 13 Ritesh Parmar Arvinod Bhai 22Yrs Male Mu. Po. Vadodara Somnaith Namasaosu Vadodara 14 Bipin Garasiya Ramesh Bhai 25 Yrs Male Vidtiyash Nagar Colony Old Ladra Nagar Vadodara 15 Vaibhav Kapsi Girish Bhai 22 Yrs Male 148, Sgavati Nagar Near Mugger School , Vadodara 16 Vaibhav Kapsi Girish Bhai 22 Yrs Male 148, Sgavati Nagar Near Mugger School , Vadodara 17 Anil Panchal Jayanti 22 Yrs Male 1350 Ambika Nagar,Gotri Road Vadodara. -

Molecular Insight Into the Genesis of Ranked Caste Populations Of

This information has not been peer-reviewed. Responsibility for the findings rests solely with the author(s). comment Deposited research article Molecular insight into the genesis of ranked caste populations of western India based upon polymorphisms across non-recombinant and recombinant regions in genome Sonali Gaikwad1 and VK Kashyap1,2* reviews Addresses: 1National DNA Analysis Center, Central Forensic Science Laboratory, Kolkata -700014, India. 2National Institute of Biologicals, Noida-201307, India. Correspondence: VK Kasyap. E-mail: [email protected] reports Posted: 19 July 2005 Received: 18 July 2005 Genome Biology 2005, 6:P10 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be This is the first version of this article to be made available publicly and no found online at http://genomebiology.com/2005/6/8/P10 other version is available at present. © 2005 BioMed Central Ltd deposited research refereed research .deposited research AS A SERVICE TO THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY, GENOME BIOLOGY PROVIDES A 'PREPRINT' DEPOSITORY TO WHICH ANY ORIGINAL RESEARCH CAN BE SUBMITTED AND WHICH ALL INDIVIDUALS CAN ACCESS interactions FREE OF CHARGE. ANY ARTICLE CAN BE SUBMITTED BY AUTHORS, WHO HAVE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ARTICLE'S CONTENT. THE ONLY SCREENING IS TO ENSURE RELEVANCE OF THE PREPRINT TO GENOME BIOLOGY'S SCOPE AND TO AVOID ABUSIVE, LIBELLOUS OR INDECENT ARTICLES. ARTICLES IN THIS SECTION OF THE JOURNAL HAVE NOT BEEN PEER-REVIEWED. EACH PREPRINT HAS A PERMANENT URL, BY WHICH IT CAN BE CITED. RESEARCH SUBMITTED TO THE PREPRINT DEPOSITORY MAY BE SIMULTANEOUSLY OR SUBSEQUENTLY SUBMITTED TO information GENOME BIOLOGY OR ANY OTHER PUBLICATION FOR PEER REVIEW; THE ONLY REQUIREMENT IS AN EXPLICIT CITATION OF, AND LINK TO, THE PREPRINT IN ANY VERSION OF THE ARTICLE THAT IS EVENTUALLY PUBLISHED. -

Origin of the Rajputs : ______

ORIGIN OF THE RAJPUTS : __________________________ There is no agreement among the scholars regarding the origin of the Rajputs. It has been opined by many scholars that the Rajputs are the descendants of foreign invaders like Sakas, Kushana, white- Hunas etc. All these foreigners, who permanently settled in India, were absorbed within the Hindu society and were accorded the status of the Kshatriyas. It was only afterwards that they claimed their lineage from the ancient Kshatriya families. The other view is that the Rajputs are the descendants of the ancient Brahamana or Kshatriya families and it is only because of certain circumstances that they have been called the Rajputs. Earliest and much debated opinion concerning the origin of the Rajputs is that all Rajput families were the descendants of the Gurjaras and the Gurjaras were of foreign origin. Therefore, all Rajput families were of foreign origin and only, later on, were placed among Indian Kshatriyas and were called the Rajputs. The adherents of this view argue that we find references to the Guijaras only after the 6th century when foreigners had penetrated in India. So, they were not of Indian origin but foreigners. Cunningham described them as the descendants of the Kushanas. A.M.T. Jackson described that one race called Khajara lived in Arminia in the 4th century. When the Hunas attacked India, Khajaras also entered India and both of them settled themselves here by the beginning of the 6th century. These Khajaras were called Gurjaras by the Indians. Kalhana has narrated the events of the reign of Gurjara king, Alkhana who ruled in Punjab in the 9th century. -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) --~92f---- CENSUS O}-' INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 oP. or 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 0 .. z 0", '" o~ Z '" ::::::::::::::::3i=:::::::::=:_------_:°i-'-------------------T~ uJ ~ :2 I I I .,0 ..rtJ . I I I I . ..,N I 0-t,... 0 <I °...'" C/) oZ C/) ?!: o - UJ z 0-t 0", '" '" Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-} CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAl- GoVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-:Gujatat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Eep8rt 1-·B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I~C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables n-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-lV-C) II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) Il-C Cultural and Migration Tables IU Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Seleted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Fest,ivals VIlI-A Administration Report-EnumeratiOn) Not for Sale VllI-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CO NTF;N'TS Table Pages Note 1- 6 SCT-I PART-A Industrial Classification of Persons at Work and Non·workers by Sex for Scheduled Castes . -

The Educational Problems Op Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe School and College Students in India

THE EDUCATIONAL PROBLEMS OP SCHEDULED CASTE AND SCHEDULED TRIBE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE STUDENTS IN INDIA (A Statistical Profile) Prepared for the Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi - By VIMAL P.SHAH Department of Sociology, Gujarat University, AHMEDABAD. NIEPA DC IH lllllll D00434 1975 CENTRE FOR REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, Post Box No 38, Dangore Street, Nanpura, SURAT : 395 001 G U J A R A T T ... U cw Delhi-llOOlT MEMBERS OF CO-ORDINATING COMMITTEE 1. Yogesh Atal 2. Ajit K. Danda 3. Ramkrishna Mukherjee 4. Vimal P* Shah 5. Yogendra Singh 6# Suma Ctiitnis Jt. Convener ?. I. P. Besai Convener PREFACE The Indian Council of Social Science Research brought together a group of social scientists from all over the country to design and execute a nation wide study of the~educational problems of high school and college students belonging to the sche duled castes and tribes. For this purpose, the ICSSR constituted a Co-ordinating Committee, and charged it with the task of designing and executing the study with the help of several other social scientists selected as project directors in diffe rent states. The major responsibility of the Co ordinating Committee was to articulate the research problem, to design sampling plan, to construct the instrument for data-collection, to centrally compu terize and analyse data, and to provide broad guidelines to the project directors in the task of conducting the study in their respective states. The responsibility of the project directors was to collect relevant data from secondary sources for the ^irpDse of preparing state level profiles, to work .out specific sampling plans for their state, to translate the data-collection instrument into the regional language, to collect and code data, and finally to prepare research reports. -

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAJAVADA ASMABANU ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 2 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat JADAV ARVINDKUMA ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF R TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 3 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PATEL HARSHITKUM ENGINEERING AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF AR TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 4 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TANNA DUSHYANT ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 5 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PADIA NOOTAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 6 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAITHATHA SAVAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 7 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat DAVE MALAY ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 8 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat SINGH KARISHMA ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 9 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat CHAVADA SUJIT ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY COMMUNICATIONS ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 10 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat ROY MALINI ENGINEERING AND CIVIL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF CHOUDHURY TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 11 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat VYAS CHANDRESHK ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF UMAR TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 12 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TRIVEDI RINKY MANAGEMENT BUSINESS MANAGEMENT -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) 925 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVtDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY TIrE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 nP. 9F 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 ~ ::; I I I o. I I <tJ ! I I ..,'" 0 <: • ....N UJ z With the compliments of The Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat, Ahmedabad Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-l CENSUS OP lNDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICA TrONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V -Gujarat is being published in the following pa rts : X-A General Report I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables lI-A General Population Tables II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-IV-C) H-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) II-C Cultural and Migration Tables In Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVU) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Sele ted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIlI-A Administration Report-Enumeration} Not for Sale VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX A das Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati co NTENTS Table Pa~es Note 1- -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Ahmadi in India Ansari in India Population: 73,000 Population: 10,700,000 World Popl: 151,500 World Popl: 14,792,500 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 6 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Ansari Main Language: Urdu Main Language: Urdu Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Asma Mirza Source: Biswarup Ganguly "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arora (Hindu traditions) in India Arora (Sikh traditions) in India Population: 4,085,000 Population: 465,000 World Popl: 4,109,600 World Popl: 466,100 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other People Cluster: South Asia Sikh - other Main Language: Hindi Main Language: Punjabi, Eastern Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Other / Small Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: VikramRaghuvanshi - iStock "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Badhai -

![NCERT Notes: the Rajputs [Medieval History of India Notes for UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4956/ncert-notes-the-rajputs-medieval-history-of-india-notes-for-upsc-1674956.webp)

NCERT Notes: the Rajputs [Medieval History of India Notes for UPSC]

NCERT Notes: The Rajputs [Medieval History Of India Notes For UPSC] The North Indian Kingdoms - The Rajputs The Medieval Indian History period lies between the 8th and the 18th century A.D. Ancient Indian history came to an end with the rule of Harsha and Pulakesin II. The medieval period can be divided into two stages: • Early medieval period: 8th – 12th century A.D. • Later Medieval period: 12th-18th century. About the Rajputs • They are the descendants of Lord Rama (Surya vamsa) or Lord Krishna (Chandra vamsa) or the Hero who sprang from the sacrificial fire (Agni Kula theory). • Rajputs belonged to the early medieval period. • The Rajput Period (647A.D- 1200 A.D.) • From the death of Harsha to the 12th century, the destiny of India was mostly in the hands of various Rajput dynasties. • They belong to the ancient Kshatriya families. There were nearly 36 Rajput’ clans. The major clans were: 1. The Pratiharas of Avanti 2. The Palas of Bengal 3. The Chauhans of Delhi and Ajmer 4. The Rathors of Kanauj 5. The Guhilas or Sisodiyas of Mewar 6. The Chandellas of Bundelkhand 7. The Paramaras of Malwa 8. The Senas of Bengal 9. The Solankis of Gujarat The Pratiharas 8th-11th Century A.D • The Pratiharas were also called Gurjara. • They ruled between 8th and 11th century A.D. over northern and western India. • Pratiharas: A fortification- The Pratiharas stood as a fortification of India’s defence against the hostility of the Muslims from the days of Junaid of Sind (725.A.D.) to Mahmud of Ghazni. -

Historical Perspective of Rajput Society

SOCIO - HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF RAJPUT SOCIETY DR. YASHPALSINH V. RATHOD At. Dhamboliya Dist. Arvvali (GJ) INDIA Maharaja Shree Ranjorsinh has identified Kshatriya Pedigree, as per him 16 from Sun, 4 from Moon, 2 from Nagvanshi, 3 from Rushivanshi and 11 from Agnivanshi are also Kshatriya. There are some assumptions for 36 Descent. But in sun vansh Rathod, Katchvaha, Sisodiya, Badgujar,Kathariya, Sikarval, Nikumbh and Rekvar are considered. European historian Easterson, Indian veda and cultural tradion indicates Rajputs are ancient Aaryajati. These gens are from Rajput and they had ruled India since vaidik period. That cast has provided bravely protection to our country, religion and culture. INTRODUCTION This article shows origin of Rajput society and their social, cultural, geographical, Economical and historical aspects. People from same cast who are living in different areas of Gujarat should know their Ancestor, their detail information is necessary today. Today’s young generation does not have proper information regarding their Descent.they should know their gotra and sub cast properly. They don’t believe in relation of brotherhood. If we ask question to any rauput youngster regarding their Descent and sub branch, that answer is not satisfactory. That’s why origin and historical detail study of Rathod Descent is required. Here detail information written of 36 Descent and their sub branch indicated in this article. Rathod Descent community is in majority in some areas of Gujarat, also in some part of the state there are Solanki, Chauhan, Parmar, Zala,Waghela etc… community are living. Kulgury, Bhat, Charan, Vahivarcha, Rani, Maga, Rao, Dhol community has played an important role in Indian Kshatriya gaurav gatha. -

(Amendment) Act, 1976

~ ~o i'T-(i'T)-n REGISTERED No. D..(D).71 ':imcT~~ •••••• '0 t:1t~~~<1~etkof &india · ~"lttl~ai, ~-. ...- .. ~.'" EXTRAORDINARY ~ II-aq 1 PART ll-Section 1 ~ d )\q,,~t,- .PUBLISHE:Q BY AUTHORITY do 151] itt f~T, m1l<fR, fuaq~ 20, 1976/m'i{ 29, 1898 No. ISI] NEWDELID, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, I976/BHADRA 29, I898 ~ ~ iT '~ ~ ~ ;if ri i' ~ 'r.t; ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ iT rnf ;m ~lj l Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be ftled as a separate compilat.on I MINISTRY OF LAW, JUSTICE AND COMPANY AFFAIRS (Legislative Department) New Delhi, the 20th Septembe1', 1976/Bhadra 29, 1898 (Saka) The following Act of Parliament received the assent of the President on the 18th September, 1976,and is hereby published for general informa tion:- THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES ORDERS (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1976 No· 100 OF 1976 [18th September, 1976] An Act to provide for the inclusion in, and the exclusion from, the lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, of certain castes and tribes, for the re-adjustment of representation of parliamentry and assembly constituencies in so far as such re adjustment is necessiatated by such inclusion of exclusion and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Twenty-seventh Year of the R.epublic of India as follows:- 1. (1) This Act may be called the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Short title and Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976. Com (2) It shall come into force on such date as the Central Government mence ment. may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint.