An Empirical Investigation of Variation in Caste Discrimination in Gujarat, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

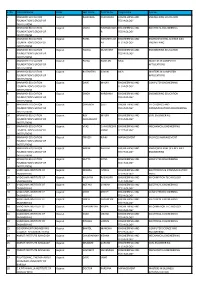

Sl. No Name of the Beneficiary Parent Name Age Gender Caste Address 1 Megh Patel Hitesh Kumar 10Yrs Male G

Sl. No Name of the Beneficiary Parent Name Age Gender Caste Address 1 Megh Patel Hitesh Kumar 10Yrs Male G. Parnashil Residency Bwehind Krishna Park Ajwa Waghod Ring Road, Vadodara. 2 Mital Ben Vinod Bhai 11Yrs Female 69-Janka Nagar, Society Mothers School Road, Near Jailar Malenagar. 3 Nisargohil Alpesh Singh 7Yrs Male C-15, Kiritmandir, Staff Quarters, Near Aaradana Cinema, Saltwada, Vadodara. 4 Manav Patel Vasanth Bhai 11Yrs Male Sri Malenagar, Ambika Nagar, Pachal Svvast, Vododara 5 Devparte Dinesh Bhai 7Yrs Male 1-Tej Quarters Behind Urmi Apartment, Fateachgunj, Vadodara 6 Deepiika Pagare Kishore 7Yrs Female Gokul Nagar, Gotri Road. 7 Vrushika Patel Vishnu Bhai 10 Yrs Female Parot Faliyu-1Vadsar, Gam, Vadodara Mandal 8 Faiza Patel Ismail 9Yrs Female 3-17, Madura Ramalesociety Near Jp Poloce Station, Tandaza. 9 Priyansh Patel Mayanek Patel 10 Yrs Male A-7-Shanti Kunj Soc Opp Raj Nagar Arunachal Samia Road, Vadodara 10 Dakshparekam Umesh Bhai 10Yrs Male Plot-83, Eev Nagar, 2 Old Pared Road, Biwualipura 11 Rana Harsh Kiran Kumar 11Yrs Male C-21, Saurabhtenament,Nrch Vidiyilaya 12 Nishth Shah Arvinod Bhai 25Yrs Male 27, Divyak Society, Mala Pur Vadodara. 13 Ritesh Parmar Arvinod Bhai 22Yrs Male Mu. Po. Vadodara Somnaith Namasaosu Vadodara 14 Bipin Garasiya Ramesh Bhai 25 Yrs Male Vidtiyash Nagar Colony Old Ladra Nagar Vadodara 15 Vaibhav Kapsi Girish Bhai 22 Yrs Male 148, Sgavati Nagar Near Mugger School , Vadodara 16 Vaibhav Kapsi Girish Bhai 22 Yrs Male 148, Sgavati Nagar Near Mugger School , Vadodara 17 Anil Panchal Jayanti 22 Yrs Male 1350 Ambika Nagar,Gotri Road Vadodara. -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) --~92f---- CENSUS O}-' INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 oP. or 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 0 .. z 0", '" o~ Z '" ::::::::::::::::3i=:::::::::=:_------_:°i-'-------------------T~ uJ ~ :2 I I I .,0 ..rtJ . I I I I . ..,N I 0-t,... 0 <I °...'" C/) oZ C/) ?!: o - UJ z 0-t 0", '" '" Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-} CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAl- GoVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-:Gujatat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Eep8rt 1-·B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I~C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables n-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-lV-C) II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) Il-C Cultural and Migration Tables IU Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Seleted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Fest,ivals VIlI-A Administration Report-EnumeratiOn) Not for Sale VllI-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CO NTF;N'TS Table Pages Note 1- 6 SCT-I PART-A Industrial Classification of Persons at Work and Non·workers by Sex for Scheduled Castes . -

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAJAVADA ASMABANU ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 2 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat JADAV ARVINDKUMA ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF R TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 3 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PATEL HARSHITKUM ENGINEERING AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF AR TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 4 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TANNA DUSHYANT ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 5 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PADIA NOOTAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 6 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAITHATHA SAVAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 7 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat DAVE MALAY ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 8 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat SINGH KARISHMA ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 9 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat CHAVADA SUJIT ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY COMMUNICATIONS ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 10 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat ROY MALINI ENGINEERING AND CIVIL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF CHOUDHURY TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 11 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat VYAS CHANDRESHK ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF UMAR TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 12 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TRIVEDI RINKY MANAGEMENT BUSINESS MANAGEMENT -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) 925 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVtDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY TIrE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 nP. 9F 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 ~ ::; I I I o. I I <tJ ! I I ..,'" 0 <: • ....N UJ z With the compliments of The Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat, Ahmedabad Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-l CENSUS OP lNDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICA TrONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V -Gujarat is being published in the following pa rts : X-A General Report I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables lI-A General Population Tables II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-IV-C) H-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) II-C Cultural and Migration Tables In Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVU) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Sele ted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIlI-A Administration Report-Enumeration} Not for Sale VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX A das Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati co NTENTS Table Pa~es Note 1- -

(Amendment) Act, 1976

~ ~o i'T-(i'T)-n REGISTERED No. D..(D).71 ':imcT~~ •••••• '0 t:1t~~~<1~etkof &india · ~"lttl~ai, ~-. ...- .. ~.'" EXTRAORDINARY ~ II-aq 1 PART ll-Section 1 ~ d )\q,,~t,- .PUBLISHE:Q BY AUTHORITY do 151] itt f~T, m1l<fR, fuaq~ 20, 1976/m'i{ 29, 1898 No. ISI] NEWDELID, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, I976/BHADRA 29, I898 ~ ~ iT '~ ~ ~ ;if ri i' ~ 'r.t; ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ iT rnf ;m ~lj l Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be ftled as a separate compilat.on I MINISTRY OF LAW, JUSTICE AND COMPANY AFFAIRS (Legislative Department) New Delhi, the 20th Septembe1', 1976/Bhadra 29, 1898 (Saka) The following Act of Parliament received the assent of the President on the 18th September, 1976,and is hereby published for general informa tion:- THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES ORDERS (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1976 No· 100 OF 1976 [18th September, 1976] An Act to provide for the inclusion in, and the exclusion from, the lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, of certain castes and tribes, for the re-adjustment of representation of parliamentry and assembly constituencies in so far as such re adjustment is necessiatated by such inclusion of exclusion and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Twenty-seventh Year of the R.epublic of India as follows:- 1. (1) This Act may be called the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Short title and Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976. Com (2) It shall come into force on such date as the Central Government mence ment. may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. -

REVISION of 'Tlfesjjist.'Vof SCHEDULED Ofgtes Anfi

REVISIONv OF 'TlfEsJjIST.'VOf Svv'vr-x'- " -?>-•'. ? ••• '■gc^ ’se v ^ - - ^ r v ■*■ SCHEDULED OfgTES ANfi SCHEDULED-TIBBS' g o VESNMEbrr pF ,i^d£4 .DEI^Ap’MksfT OF.SOCIAL SEmFglTY THE REPORT OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE REVISION OF THE LISTS OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SECURITY CONTENTS PART I PTER I. I n t r o d u c t i o n ............................................................. 1 II. Principles and P o l i c y .................................................... 4 III. Revision o f L i s t s .............................................................. 12 IV. General R eco m m en d a tio n s.......................................... 23 V. Appreciation . 25 PART II NDJX I. List of Orders in force under articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution ....... 28 II. Resolution tonstituting the Committee . 29 III, List of persons 'who appeared before the Committee . 31 (V. List of Communities recommended for inclusion 39 V. List of Communities recommended for exclusion 42 VI, List of proposals rejected by the Committee 55 SB. Revised Statewise lists of Scheduled Castes and . Scheduled T r i b e s .................................................... ■115 CONTENTS OF APPENDIX 7 1 i Revised Slantwise Lists pf Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Sch. Sch. Slate Castes Tribes Page Page Andhra Pracoih .... 52 9i rtssam -. •S'S 92 Bihar .... 64 95 G u j a r a i ....................................................... 65 96 Jammu & Kashmir . 66 98 Kerala............................................................................... 67 98 Madhya Pradesh . 69 99 M a d r a s .................................................................. 71 102 Maharashtra ........................................................ 73 103 Mysore ....................................................... 75 107 Nagaland ....................................................... 108 Oriisa ....................................................... 78 109 Punjab ...... 8i 110 Rejssth&n ...... -

Contributionstoa292fiel.Pdf

Field Museum OF > Natural History o. rvrr^ CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF IRAN BY HENRY FIELD CURATOR OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 29, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 15, 1939 PUBLICATION 459 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES 1. Basic Mediterranean types. 2. Atlanto- Mediterranean types. 3. 4. Convex-nosed dolichocephals. 5. Brachycephals. 6. Mixed-eyed Mediterranean types. 7. Mixed-eyed types. 8. Alpinoid types. 9. Hamitic and Armenoid types. 10. North European and Jewish types. 11. Mongoloid types. 12. Negroid types. 13. Polo field, Maidan, Isfahan. 14. Isfahan. Fig. 1. Alliance Israelite. Fig. 2. Mirza Muhammad Ali Khan. 15-39. Jews of Isfahan. 40. Isfahan to Shiraz. Fig. 1. Main road to Shiraz. Fig. 2. Shiljaston. 41. Isfahan to Shiraz. Fig. 1. Building decorated with ibex horns at Mahyar. Fig. 2. Mosque at Shahreza. 42. Yezd-i-Khast village. Fig. 1. Old town with modern caravanserai. Fig. 2. Northern battlements. 43. Yezd-i-Khast village. Fig. 1. Eastern end forming a "prow." Fig. 2. Modern village from southern escarpment. 44. Imamzadeh of Sayyid Ali, Yezd-i-Khast. 45. Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. Entrance to Imamzadeh of Sayyid Ali. Fig. 2. Main gate and drawbridge of old town. 46. Safavid caravanserai at Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. Inscription on left wall. Fig. 2. Inscription on right wall. 47. Inscribed portal of Safavid caravanserai, Yezd-i-Khast. 48. Safavid caravanserai, Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. General view. Fig. 2. South- west corner of interior. 49-65. Yezd-i-Khast villagers. 66. Kinareh village near Persepolis. 67. Kinareh village. -

Review of Literature

Chapter 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE Review of Literature Review of Literature Clothing reflects about one’s membership in a culture and of the many groups he/ she belongs or relates to within a culture. Costumes forms an important element amongst all the cultural expressions defining one’s identity in India. Eicher writes ethnic dress is a notable aspect of ethnicity. Again, Claus and Korom states that a folkloristic or an ethnographic study includes the study of culture, history and psychology. These represent the three fundamental dimensions in which expression exists. What forms and shapes any expression is the past (history, tradition), the outer context (Culture) and the inner motivation (psychology). And there are always other pertinent lines of inquiry- political structure, economics, geography and others (Claus P. and Korom F.,1991: 41). Therefore, the present chapter aims to take a preliminary glimpse of the factors coming under the purview of the subject under study. 2.1. Theoretical review 2.1.1. Accounts on Indian Cotton Textiles: History, trade, production and evolution 2.1.2. Salience of folk costumes and textiles in India 2.1.3. Gujarati textiles: Production, trade and consumption 2.1.4. Traditional draped garments of men in India 2.1.5. Geography and morphology of producers and patrons 2.1.5.1. The Locales: Geography and culture (Saurashtra, Kachchh, North Gujarat, Ahmedabad) 2.1.5.2. People: (Vankar, Barot, Vaniya, Bharward, Rabari, Charan, Ahir) 2.1.6. Cultural contexts of commodities: Importance of products in social life 2.1.7. Handloom Industry in India 2.1.7.1. -

The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 1 (C.O.19)

THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950 1 (C.O.19) In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of article 341 of the Constitution of India, the President, after consultation with the Governors and Rajpramukhs of the States concerned, is pleased to make the following Order, namely:- 1. This Order may be called the Constitution (Scheduled Caste) Order, 1950. 2. Subject to the provisions of this Order, the castes, races or tribes or parts of, or groups 2 3 7 8 within, castes or tribes specified in [Parts to XXII] XXIII XXIV of the Schedule to this Order shall, in relation to the States to which those Parts respectively relate, be deemed to be Scheduled Castes so far as regards member thereof resident in the localities specified in relation to them in those Parts of that Schedule. 4[3. Notwithstanding anything contained in paragraph 2, no person who professes a religion different from the Hindu 5[, the Sikh or the Buddhist] religion shall be deemed to be a member of a Scheduled Caste.] 6[4. Any reference in this Order to a State or to a district or other territorial division thereof shall be construed as a reference to the State, district or other territorial division as constituted on the 1st day of May, 1976.] ____________________________________________________________________ 1. Published with the Ministry or Law Notification No. S.R.O. 385, dated the 10th August, 1950, Gazette of India, Extraordinary, 1950, Part II, Section 3, page 163. 2. Subs. by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Lists (Modification) Order, 1956. 3. -

Consolidated Statement Showing Scheduled Castes, Scheduled

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I INDIA PART V-B (iii) Consolidated Statement Showing Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Denotified Communities and other Communities of Similar Status III Different Statute ~Censllses Starting from 1921 ~---""" ~ \\EE!f1.i1At: 7i1?;" ~ .. ;,-,..- - -.., .... ', '" , ~ r "","II' " t:( ., 'DR~ r " Y;;. t -;.. \. ~-," 0 .. ", ~ ) ~ '" .".._\... ./,~ '''':' ......", '-. -.-- _-"EY '* 'Vi.w D-'--~\· - , A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service Registrar General and ex-officio Census Commissioner for JnQia CENSUS OF INDIA 1961-UNION PUBLICATIONS .. General Report on the Census: PART I-A General Report PART I-A (i) (Text) Levels of Regional Development in India PART I-A (ii) (Tables) Levels of Regional Development in India PART I-B Vital Statistics of the decade PART I-C Subsidiary Tables -EART II .. .. Cemu" Tables on Population: )PART If-A(i) General Population Tables PART lI-A(ii) Union Primary CenslIs Abstracts PART IT-D(i) General Economic Tables ( B-1 to B-IV) PART IT-B(ii) General Economic Tables (B-V) PART If-f3(iii) General Economic Tables (B-VI to B-IX) PART JI. -C(i) Social and Cultural Tables PART H-C(ii) Language' Tables PART II-C(iii) Migration Tables ( D-T to D-V) PART II-C(iv) Migration Tables CD-VI) PART III . " HOllsehold Economic Tables: PART rrr (i) lIomehold Economic Tables (14 States) PA RT ITT Oi) Household Economic Tables (India, Uttar Pradesh and Union Territories) PART IV .. .. Report on Housing and Establishments PART IV--A(i) Housing Report PART IV-A(ii) Report on Industrial Establish\!)ents PART IV-A(iii)Housc Types and Village layouts PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V . -

Affiliated Colleges & Recognised Institutions Part

AFFILIATED COLLEGES & RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS PART (A) AFFILIATED COLLEGES ARTS COLLEGES : (14) BD ARTS (024) B. D. Arts College for Women, City Campus, Opp. Din bai Tower, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad – 380 001. (Founded 1956) (G) (NAAC - B Grade) Time : 12-00 to 5-00 (079) 25500004 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Economics, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Home Science, Psychology, Sanskrit, Sociology, B.A. (Subsi.) Persian, Prakrit, Political Science, Statistical Method, M.A. Home Science, Sanskrit. Principal : Dr. Geetaben P. Mehta (079) 26611940 (M) 9825017019 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected] CU ARTS ( 036) C. U. Shah Arts College, Lal Darwaja, Nr. Dinbai Tower, Ahmedabad – 380 001. (Founded 1960) (E+G) (NAAC - B Grade) Time : 7-45 to 12-40 Tele Fax : (079) 25506703 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Gujarati, Hindi, Sanskrit, English, Economics, Political Science, History, Statistical Method, Psychology, Sociology, M.A. Psychology. Principal : Dr. S. K. Trivedi (Offg) (079) 27461233 (M) 9426048955 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] MANI ARTS (384) Goverment Arts College, Bihari mill compound, Khokhra road, Maninagar (East), Ahmedabad – 380 008. (Founded 2007) (G) Time : 11-00 to 16-00 (079) 22932516 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Economics, English, Gujarati, Psychology, Sanskrit, (Subsi.) Indology Principal : Dr. Geetaben G. Pandya (079) 26302184 (M) 9426709133 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected] LD ARTS (005) L. D. Arts College, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad – 380 009. (Founded 1937) (E + G) (NAAC - A Grade) Time : 7-30 to 12-30 (079) 26306619 Fax : 26302260 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) English, Sanskrit, Gujarati, History, Economics, Hindi, Political Science, Psychology, Sociology, Geography, B.A. -

Gujarat UPG List 2018

State People Group Primary Language Religion Pop. Total % Christian Gujarat Adi Andhra Telugu Hinduism 350 0 Gujarat Adi Karnataka Kannada Hinduism 70 0 Gujarat Agamudaiyan Tamil Hinduism 40 0 Gujarat Agamudaiyan Nattaman Tamil Hinduism 20 0 Gujarat Agaria (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 460 0 Gujarat Ager (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 1390 0 Gujarat Agri Marathi Hinduism 62370 0 Gujarat Ahmadi Urdu Islam 5550 0 Gujarat Andh Marathi Hinduism 240 0 Gujarat Ansari Urdu Islam 127030 0 Gujarat Arab Arabic, Mesopotamian Islam 270 0 Gujarat Arain (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 150 0 Gujarat Arayan Malayalam Hinduism 150 0 Gujarat Arora (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 464520 0 Gujarat Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other / Small 1110 0 Gujarat Assamese (Muslim traditions) Assamese Islam 20 0 Gujarat Atari Urdu Islam 1300 0 Gujarat Babria Gujarati Hinduism 25520 0 Gujarat Badhai (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 586470 0 Gujarat Badhai (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 2870 0 Gujarat Badhai Gandhar Gujarati Hinduism 21590 0 Gujarat Badhai Kharadi Gujarati Hinduism 3050 0 Gujarat Bafan Kacchi Islam 460 0 Gujarat Bagdi Hindi Hinduism 540 0 Gujarat Bagdi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism 460 0 Gujarat Bahna (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 50 0 Gujarat Bahrupi Marathi Hinduism 60 0 Gujarat Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 419280 0 Gujarat Baiti Bengali Hinduism 60 0 Gujarat Bajania Gujarati Hinduism 24990 0 Gujarat Bakad Kannada Hinduism 960 0 Gujarat Balasantoshi Marathi Hinduism 3270 0 Gujarat Balija (Hindu traditions)