Bach Notes No. 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

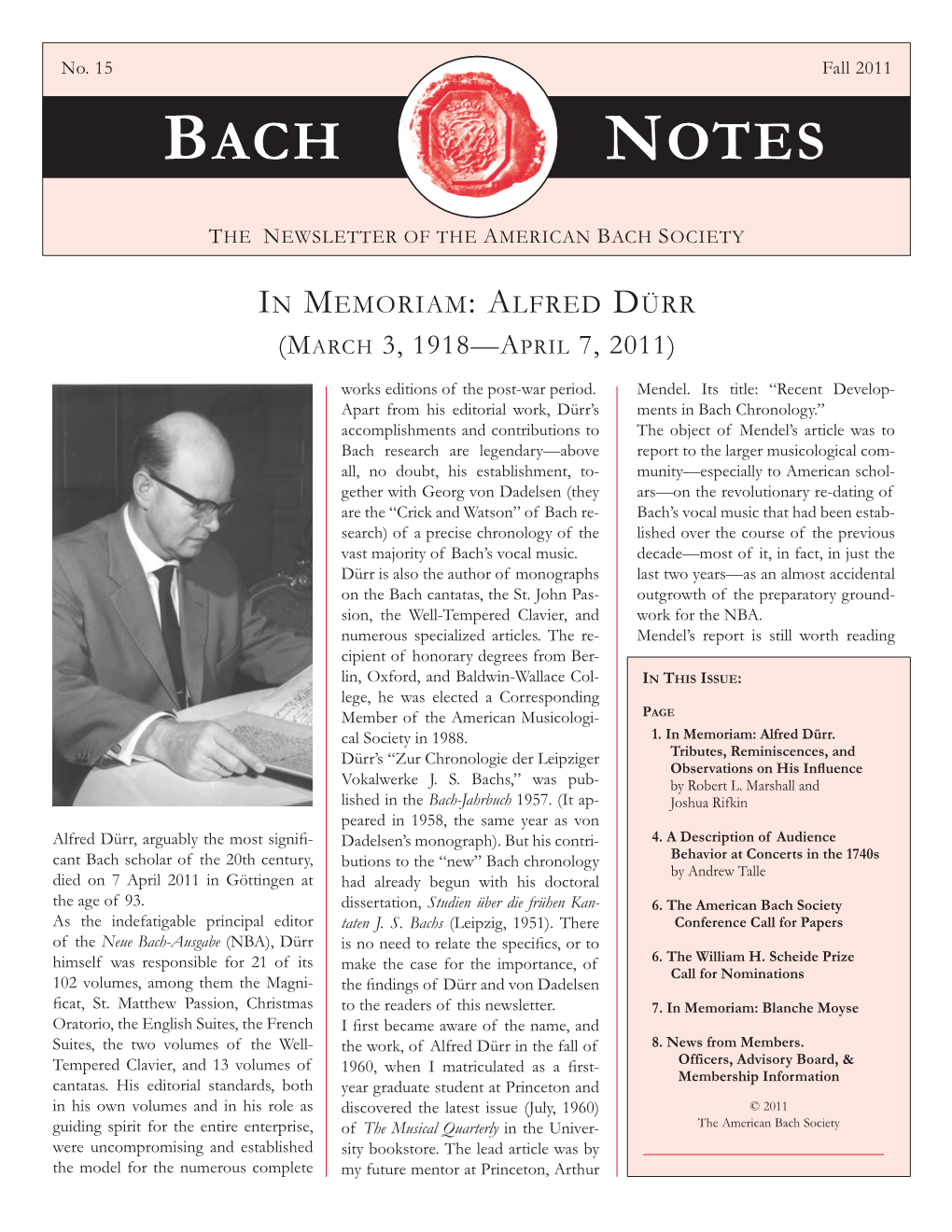

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

Bach: Goldberg Variations

The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge Final Logo Brand Extension Logo 06.27.12 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay | harp PARKER RAMSAY Parker Ramsay was the first American to hold the post of Organ Scholar at King’s, from 2010–2013, following a long line of prestigious predecessors. Organ Scholars at King’s are undergraduate students at the College with a range of roles and responsibilities, including playing for choral services in the Chapel, assisting in the training of the probationers and Choristers, and conducting the full choir from time to time. The position of Organ Scholar is held for the duration of the student’s degree course. This is Parker’s first solo harp recording, and the second recording by an Organ Scholar on the College’s own label. 2 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay harp 3 CD 78:45 1 Aria 3:23 2 Variatio 1 1:57 3 Variatio 2 1:54 4 Variatio 3 Canone all’Unisono 2:38 5 Variatio 4 1:15 6 Variatio 5 1:43 7 Variatio 6 Canone alla Seconda 1:26 8 Variatio 7 al tempo di Giga 2:24 9 Variatio 8 2:01 10 Variatio 9 Canone alla Terza 1:49 11 Variatio 10 Fughetta 1:45 12 Variatio 11 2:22 13 Variatio 12 Canone alla Quarta in moto contrario 3:21 14 Variatio 13 4:36 15 Variatio 14 2:07 16 Variatio 15 Canone alla Quinta. Andante 3:24 17 Variatio 16 Ouverture 3:26 18 Variatio 17 2:23 19 Variatio 18 Canone alla Sesta 1:58 20 Variatio 19 1:45 21 Variatio 20 3:10 22 Variatio 21 Canone alla Settima 2:31 23 Variatio 22 alla breve 1:42 24 Variatio 23 2:33 25 Variatio 24 Canone all’Ottava 2:30 26 Variatio 25 Adagio 4:31 27 Variatio 26 2:07 28 Variatio 27 Canone alla Nona 2:18 29 Variatio 28 2:29 30 Variatio 29 2:04 31 Variatio 30 Quodlibet 2:38 32 Aria da Capo 2:35 4 AN INTRODUCTION analysis than usual. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Du Treuer Gott Leipzig Cantatas BWV 101 - 115 - 103

Johann Sebastian Bach Du treuer Gott Leipzig Cantatas BWV 101 - 115 - 103 Collegium Vocale Gent Philippe Herreweghe Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott, BWV 101 Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit, BWV 115 Ihr werdet weinen und heulen, BWV 103 Dorothee Mields Soprano Damien Guillon Alto Thomas Hobbs Tenor Peter Kooij Bass Collegium Vocale Gent Philippe Herreweghe Menu Tracklist ------------------------------ English Biographies Français Biographies Deutsch Biografien Nederlands Biografieën ------------------------------ Sung texts Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott, BWV 101 [1] 1. Coro: Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott ______________________________________________________________7’44 [2] 2. Aria (tenor): Handle nicht nach deinen Rechten ________________________________________________________3’30 [3] 3. Recitativo e choral (soprano): Ach! Herr Gott, durch die Treue dein__________________________________2’13 [4] 4. Aria (bass): Warum willst du so zornig sein? ___________________________________________________________ 4’14 [5] 5. Recitativo e choral (tenor): Die Sünd hat uns verderbet sehr _________________________________________ 2’11 [6] 6. Aria (soprano, alto): Gedenk an Jesu bittern Tod _______________________________________________________5’59 [7] 7. Choral: Leit uns mit deiner rechten Hand _______________________________________________________________0’55 Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit, BWV 115 [8] 1. Coro: Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit ____________________________________________________________________4’00 -

JB17 Poeschel 2018 10 30 Familie Graun in Preußen Manuskript WP2

Wilhelm Poeschel – Familie Graun in Preußen 3. Quellen zu biografischen Daten der Familien Johann Gottlieb und Carl Heinrich Graun (Auswahl) Samuel Schmiel Bestattungsbuch St. Petri, ELAB Sig. 5820-1, S. 107 (*1658; †1.9.1734) 1734 I September I 1. Herr Samuel Schmiel, Königl. Geheimer Kammer Diener, 77. Jahr, am Schlagfluß, den 5. Anna Regina Schmiel, Bestattungsbuch St. Petri, ELAB Sig. 5820-1, S. 8 geb. Thering 1704 Aug. 15. Hr. Geheimer Cammerdiener Schmieles Ehe Frau, in S.P. (*um 1680; †15.8.1704) Friederich Schmiel Taufbuch St. Petri, ELAB Sig. 5789-2, S. 596 (*17.5.1700; †2.8.1700) Pr: Herr Samuel Schmiel Ser: churfürstlichen Herrn (?) brandng geheimer Cammer-Diener I Mr: Fr: Anna Regina geborene Theringen laßen Tauffen am 17 May ihr am 14 deßelbh Monath zwischen 3 und ½ 4 Uhr geborenes Söhn- lein mit dem Nahmen I Friedrich I Die Gevattern waren I S: Churfürstl. Durch- laucht Friederich an deßen Platz der Hoffmarschall Excellents d(er) Herr von Wusrau (?) zugegen gewest. I Herr Lucas Heinrich Therig Archediaconus d(er) Peter Kirch. Die Fr: Kriegs Rähtin v. Kraut, geborene Schindlern, Die Frau Mommortin, Loff […][…] (?) Bestattungsbuch St. Petri, ELAB Sig. 5820-1, S. 1536 1700, Augt. 2. Herr Geheimer Cammerdiener Schmiels Kind, zu S.P. Anna Theodora Schmiel, Taufbuch Friedrich Werdersche Kirche, ELAB Sig. 5117-1, S. 151 geb. Simonetti, 1684, 27 December Inf: Anna Theodora I Pat: Johann Simonetti, Stucator156 I Mat: Euphrosina Hoffekuntzin I Pathen I 1 Hr. Christian Kuntzleben. 2 Hr. (#27.12.1684; †15.5.1708) Peter Jenicke. 3 Jfr: Scharlotta …(?) 4 Fr […] 5 Fr. -

MTO 19.3: Brody, Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn (Cambridge University Press, 2012) Christopher Brody KEYWORDS: Bach, Bach reception, Mozart, fugue, chorale, Well-Tempered Clavier Received July 2013 [1] Historical research on Johann Sebastian Bach entered its modern era in the late 1950s with the development, spearheaded by Alfred Dürr, Georg von Dadelsen, and Wisso Weiss, of the so-called “new chronology” of his works.(1) In parallel with this revolution, the history of the dissemination and reception of Bach was also being rewritten. Whereas Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel wrote, in 1945, that “Bach and his works ... [were] practically forgotten by the generations following his” (358), by 1998 Christoph Wolff could describe the far more nuanced understanding of Bach reception that had arisen in the intervening years in terms of “two complementary aspects”: on the one hand, the beginning of a more broadly based public reception of Bach’s music in the early nineteenth century, for which Mendelssohn’s 1829 performance of the St. Matthew Passion represents a decisive milestone; on the other hand, the uninterrupted reception of a more private kind, largely confined to circles of professional musicians, who regarded Bach’s fugues and chorales in particular as a continuing challenge, a source of inspiration, and a yardstick for measuring compositional quality. (485–86) [2] In most respects it is with the latter (though chronologically earlier) aspect that Matthew Dirst’s survey Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn concerns itself, serving as a fine single-volume introduction to the “private” side of Bach reception up to about 1850. -

Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig from 1723 to 1750*

Understanding Bach, 12, 111–125 © Bach Network UK 2017 Young Scholars’ Forum Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig * from 1723 to 1750 NOELLE HEBER It was his post as Music Director and Cantor at the Thomasschule that primarily marked Johann Sebastian Bach’s twenty-seven years in Leipzig. The tension around the unstable income of this occupation drove Bach to write his famous letter to Georg Erdmann in 1730, in which he expressed a desire to seek employment elsewhere.1 The difference between his base salary of 100 Thaler and his estimated total income of 700 Thaler was derived from legacies and foundations, funerals, weddings, and instrumental maintenance in the churches, although many payment amounts fluctuated, depending on certain factors such as the number of funerals that occurred each year. Despite his ongoing frustration at this financial instability, it seems that Bach never attempted to leave Leipzig. There are many speculations concerning his motivation to stay, but one could also ask if there was a financial draw to settling in Leipzig, considering his active pursuit of independent work, which included organ inspections, guest performances, private music lessons, publication of his compositions, instrumental rentals and sales, and, from 1729 to 1741, direction of the collegium musicum. This article provides a new and detailed survey of these sources of revenue, beginning with the supplemental income that augmented his salary and continuing with his freelance work. This exploration will further show that Leipzig seems to have been a strategic location for Bach to pursue and expand his independent work. -

A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-2-2014 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Labadorf, Thomas A., "A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 332. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/332 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf, D. M. A. University of Connecticut, 2014 A new transcription of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy is presented to offset limitations of previous transcriptions by other editors. Certain shortcomings of the clarinet are addressed which add to the difficulty of creating an effective transcription for performance: the inability to sustain more than one note at a time, phrase length limited by breath capacity, and a limited pitch range. The clarinet, however, offers qualities not available to the keyboard that can serve to mitigate these shortcomings: voice-like legato to perform sweeping scalar and arpeggiated gestures, the increased ability to sustain melodic lines, use of dynamics to emphasize phrase shapes and highlight background melodies, and the ability to perform large leaps easily. A unique realization of the arpeggiated section takes advantage of the clarinet’s distinctive registers and references early treatises for an authentic wind instrument approach. A linear analysis, prepared by the author, serves as a basis for making decisions on phrase and dynamic placement. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

A Non-Definitive List of Most of the Concerts and Work (And the Odd Function) Presented, Promoted and Performed by the Bach Society of Queensland and the Bach Choir

A non-definitive list of most of the concerts and work (and the odd function) presented, promoted and performed by The Bach Society of Queensland and the Bach Choir. Regular occasions such as The Annual Bach Prizes, some Messiah Performances, Carol Singing and Soirees have not all been listed individually each and every year. Blue denotes items of significance. 1971 8 Jul First Fundraising Concert: JS Bach Sonata No 2 for Violin and Harpsichord; Granados Six Tornadillas; German lieder songs; Prokofiev 4th Piano Sonata 1 Aug The Inaugural Bach Society Concert JS Bach Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, the B-Minor Flute Suite, The Coffee Cantata 1972 18 Jun The Bach Choir under John Thompson: Vivaldi Four Violin Concertos, Klavier Concerto in B Minor; JS Bach Sinfonia Concertante in A Minor Plus three items by (their premier performance) Aug/Sept Sponsored Recitals by internationally acclaimed harpsichordist Dorothy White 27 Nov “Monday-Evening-with-Bach” free 1973 18 Feb JS Bach Concerto in F Major; Telemann Concerto in C Minor 15 Apr QYO Brass Ensemble: two Gabrieli Canzone; JS Bach Sonata No 3 for unaccompanied ‘Cello, Brandenburg Concerto No 3 21 July An instructive evening on Bach’s Preludes and Fugues 10/11 Aug JS Bach St Matthew Passion: rarely heard in Brisbane before 11 Nov JS Bach Cantata #10 Meine Seel erhebt den Herren, Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D 1974 21 Apr At home - soiree. The first of many. JS Bach Ah My Savior from Christmas Oratorio, Have Mercy Lord from St Matthew Passion 1975 26 May Together with Concert Society Orchestra - JS Bach Magnificat : (the biggest challenge the choir had yet faced); Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia in E for Two Orchestras, Op 18 No 5; JS Bach The Third Brandenburg Concerto in G for Strings 16 Jun Bach-B-Que at Rosevale, near Ipswich the first of many. -

The American Bach Society the Westfield Center

The Eastman School of Music is grateful to our festival sponsors: The American Bach Society • The Westfield Center Christ Church • Memorial Art Gallery • Sacred Heart Cathedral • Third Presbyterian Church • Rochester Chapter of the American Guild of Organists • Encore Music Creations The American Bach Society The American Bach Society was founded in 1972 to support the study, performance, and appreciation of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the United States and Canada. The ABS produces Bach Notes and Bach Perspectives, sponsors a biennial meeting and conference, and offers grants and prizes for research on Bach. For more information about the Society, please visit www.americanbachsociety.org. The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific 2 Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance. -

A Polonaise Duet for a Professor, a King and a Merchant: on Cantatas BWV 205, 205A, 216 and 216A by Johann Sebastian Bach 1

Understanding Bach , 2, 19-36 © Bach Network UK 2007 A Polonaise Duet for a Professor, a King and a Merchant: on Cantatas BWV 205, 205a, 216 and 216a by Johann Sebastian Bach 1 SZYMON PACZKOWSKI Bach’s cantata Zerreißet, zersprenget, zertrümmert die Gruft ( Der zufriedengestellte Aeolus or Aeolus Pacified , BWV 205) was composed in 1725 for the name-day of August Friedrich Müller, a professor of philosophy at the University of Leipzig. 2 Bach’s Collegium Musicum performed the piece on the evening of 3 August 1725 in front of the professor’s house at 2 Katharinenstraße in Leipzig. Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander) wrote the libretto 3 with its allegorical allusions to the professor’s philosophical ideas. The libretto has attracted its fair share of scholarly criticism, and indeed derision. 4 However, the circumstances of its 1 This article is part of Szymon Paczkowski’s research project, ‘The Polish Style in German Music of the Eighteenth Century: Functions and Meaning on the Example of the Work of Johann Sebastian Bach (2004–2007)’, sponsored by the State Committee for Scientific Research of the Republic of Poland. It has been prepared for publication as part of a book entitled Polish Studies on Baroque Music (in preparation) which brings together the papers presented by Polish speakers at the 12th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music in Warsaw (26–30 July 2006), and appears in ‘Understanding Bach’ courtesy of the book’s publishers, the Institute of Musicology at Warsaw University. 2 Hans-Joachim Schulze, Christoph Wolff, Bach-Compendium . Analytisch-bibliographisches Repertorium der Werke Johann Sebastian Bachs , Vokalwerke: Teil IV (further abbreviated to Bach- Compendium IV) (edn Peters, Leipzig: 1989), p. -

Bach Notes No. 14

No. 14 Spring 2011 BACH NOTES THE NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN BACH SOCIETY A NEWLY EXPANDED RESEARCH LIBRARY RENOVATIONS AT THE BACH-ARCHIV LEIPZIG has grown steadily. The primary emphasis on books and scores is supplemented by numerous special collections, including recordings, images, sculptures, posters, programs, coins, and medals, for a total of more than fifty thousand items. The constant growth of the collection over the past few decades eventually led to a lack of space. This problem was temporarily solved by removing certain materials to repositories outside After two years of renovations, the of documents and materials IN THIS ISSUE: Bach-Archiv Leipzig has moved pertaining to the life and works of PAGE back into the Bosehaus on the Johann Sebastian Bach and other 1. A Newly Expanded Research Library Thomaskirchhof. The house was musicians of his family. The core by Kristina Funk-Kunath originally built in the 16th century of the holdings consist of valuable and renovated in 1711 by J.S. manuscripts and early prints of the 2. The Bach-Jahrbuch 2010 Bach’s neighbor, Georg Heinrich 18th and 19th centuries, including by Peter Wollny Bose, who lived there with his wife the original performing materials 3. Raymond Erickson’s The Worlds of and their many musically inclined for the cycle of chorale cantatas Johann Sebastian Bach children. The renovations, which Bach composed during his second by Jason B. Grant took place under the auspices of the year in Leipzig (1724-25). Bach-Archiv’s Director, Christoph Initially conceived as an aid for 5. Markus Rathey’s book on C.