From Genotype to Phenotype: Unraveling the Complexities of Cold Adaptation in Forest Trees1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Genetic Terms for Teachers

Student Name: Date: Class Period: Page | 1 Basic Genetic Terms Use the available reference resources to complete the table below. After finding out the definition of each word, rewrite the definition using your own words (middle column), and provide an example of how you may use the word (right column). Genetic Terms Definition in your own words An example Allele Different forms of a gene, which produce Different alleles produce different hair colors—brown, variations in a genetically inherited trait. blond, red, black, etc. Genes Genes are parts of DNA and carry hereditary Genes contain blue‐print for each individual for her or information passed from parents to children. his specific traits. Dominant version (allele) of a gene shows its Dominant When a child inherits dominant brown‐hair gene form specific trait even if only one parent passed (allele) from dad, the child will have brown hair. the gene to the child. When a child inherits recessive blue‐eye gene form Recessive Recessive gene shows its specific trait when (allele) from both mom and dad, the child will have blue both parents pass the gene to the child. eyes. Homozygous Two of the same form of a gene—one from Inheriting the same blue eye gene form from both mom and the other from dad. parents result in a homozygous gene. Heterozygous Two different forms of a gene—one from Inheriting different eye color gene forms from mom mom and the other from dad are different. and dad result in a heterozygous gene. Genotype Internal heredity information that contain Blue eye and brown eye have different genotypes—one genetic code. -

Molecular Biology and Applied Genetics

MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS FOR Medical Laboratory Technology Students Upgraded Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Jimma University MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS For Medical Laboratory Technician Students Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Upgraded - 2006 In collaboration with The Carter Center (EPHTI) and The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health Jimma University PREFACE The problem faced today in the learning and teaching of Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology for laboratory technologists in universities, colleges andhealth institutions primarily from the unavailability of textbooks that focus on the needs of Ethiopian students. This lecture note has been prepared with the primary aim of alleviating the problems encountered in the teaching of Medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology course and in minimizing discrepancies prevailing among the different teaching and training health institutions. It can also be used in teaching any introductory course on medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology and as a reference material. This lecture note is specifically designed for medical laboratory technologists, and includes only those areas of molecular cell biology and Applied Genetics relevant to degree-level understanding of modern laboratory technology. Since genetics is prerequisite course to molecular biology, the lecture note starts with Genetics i followed by Molecular Biology. It provides students with molecular background to enable them to understand and critically analyze recent advances in laboratory sciences. Finally, it contains a glossary, which summarizes important terminologies used in the text. Each chapter begins by specific learning objectives and at the end of each chapter review questions are also included. -

From Genotype to Phenotype: Inferring Relationships Between Microbial Traits and Genomic Components

From genotype to phenotype: inferring relationships between microbial traits and genomic components Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf vorgelegt von Aaron Weimann aus Oberhausen D¨usseldorf,29.08.16 aus dem Institut f¨urInformatik der Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Mathemathisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨atder Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf Referent: Prof. Dr. Alice C. McHardy Koreferent: Prof. Dr. Martin J. Lercher Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung: 24.02.17 Selbststandigkeitserkl¨ arung¨ Hiermit erkl¨areich, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation eigenst¨andigund ohne fremde Hilfe angefertig habe. Arbeiten Dritter wurden entsprechend zitiert. Diese Dissertation wurde bisher in dieser oder ¨ahnlicher Form noch bei keiner anderen Institution eingereicht. Ich habe bisher keine erfolglosen Promotionsversuche un- ternommen. D¨usseldorf,den . ... ... ... (Aaron Weimann) Statement of authorship I hereby certify that this dissertation is the result of my own work. No other person's work has been used without due acknowledgement. This dissertation has not been submitted in the same or similar form to other institutions. I have not previously failed a doctoral examination procedure. Summary Bacteria live in almost any imaginable environment, from the most extreme envi- ronments (e.g. in hydrothermal vents) to the bovine and human gastrointestinal tract. By adapting to such diverse environments, they have developed a large arsenal of enzymes involved in a wide variety of biochemical reactions. While some such enzymes support our digestion or can be used for the optimization of biotechnological processes, others may be harmful { e.g. mediating the roles of bacteria in human diseases. -

Genotype-Independent Near Whole Genome Next Generation Assays for HCV Resistance Evaluation How Do We Test for HCV Ravs?

How do we test for HCV RAVs? A Technology Based Presentation Genotype-Independent Near Whole Genome Next Generation Assays for HCV Resistance Evaluation Anita Howe, Ph.D. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS British Columbia, Canada Objectives 1. Overview of key virology assays 2. Sanger population sequencing and RECall 3. Near Whole Genome HCV Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) 4. Random Primer NGS assay for Mixed Infection 5. Probe Enrichment Key HCV Assays for Resistance Testing Viral Load Genotyping Sequencing Phenotypic Assays Branched DNA Line-Probe Sanger Population ® VERSANT HCV RNA Hybridization Sequencing F.L. Stable Replicons 3.0 branched DNA VERSANT® HCV High throughput • GT1a_H77 (Bayer/Siemens) GENOTYPE 2.0 [LIPA] LOD ~20% • GT1b_con1 (Innogenetics) • GT 2a_JFH1 RT-PCR Clonal Sequencing • GT 3a_S52 • ABBOTT REAL- RT-PCR Labor intensive • GT 4a_ED43 TIME HCV RT-PCR ABBOTT REAL-TIME HCV • GT 5a_SA1 (Abbott) Linkage of mutations GENOTYPE II (Abbott) • GT 6a_consensus • HCV SUPERQUANT (National Genetics Allele-specific Real-time Institute) Direct Sequencing Chimeric/Transient • COBAS AmpliPrep/ TRUGENE DIRECT DNA PCR Replicons in Limit to known mutations COBAS TaqMan HCV SEQUENCING (Bayer/ • GT1a_H77 Siemens) TEST (Roche • GT1b_con1 Molecular Systems) • GT2a_JFH1 Serotyping Next Generation Transcription- MUREX HCV Sequencing Infectious HCV SEROTYPING (Abbott) Mediated Illumina, Ion Torrent, 454 • GT1a_H77 Amplification (Roche), PyroMark (Qiagen), • GT 2a_JFH1 VERSANT HCV RNA ABI SOLiD, SMRT (Pac Bio) (Siemens) Ø Sensitive Reporter Assay Ø 5’UTR/Core/NS5B Ø GT1 – 6 Ø Medium-high throughput SEAP for NS3 Ø High costs Ø 5’UTR/Core Ø Limited subtype Ø 9.6 – 108 IU/mL information Enzymatic assays NS3, NS5B RECall Web Based Sequence Analysis http://pssm.cfenet.ubc.ca/account/login Woods et al. -

Punnett Squares

What is Genetics? Genetics is the scientific study of heredity What is a Trait? A trait is a specific characteristic that varies from one individual to another. Examples: Brown hair, blue eyes, tall, curly What is an Allele? Alleles are the different possibilities for a given trait. Every trait has at least two alleles (one from the Examples of Alleles: A = Brown Eyes mother and one from the a = Blue Eyes father) B = Green Eyes b = Hazel Eyes Example: Eye color – Brown, blue, green, hazel What are Genes? Genes are the sequence of DNA that codes for a protein and thus determines a trait. Gregor Mendel Father of Genetics 1st important studies of heredity Identified specific traits in the garden pea and studied them from one generation to another Mendel’s Conclusions 1.Law of Segregation – Two alleles for each trait separate when gametes form; Parents pass only one allele for each trait to each offspring 2.Law of Independent Assortment – Genes for different traits are inherited independently of each other Dominant vs. Recessive Dominant - Masks the other trait; the trait that shows if present Represented by a capital letter R Recessive – An organism with a recessive allele for a particular trait will only exhibit that trait when the dominant allele is not present; Will only show if both alleles are present Represented by a lower case letter r Dominant & Recessive Practice T – straight hair t - curly hair TT - Represent offspring with straight hair Tt - Represent offspring with straight hair tt - Represents offspring with curly hair Genotype vs. Phenotype Genotype – The genetic makeup of an organism; The gene (or allele) combination an organism has. -

Genotype to Phenotype V2

From Genotype to Phenotype: Understanding the Introduction of Phenotypic Variations by Random Mutation Background In biology, the term phenotype refers to the observable traits of individuals that arise from the causal interaction of their genotype with the environment. “Observable” is meant in the scientific sense and so is not limited to traits that are directly visible. Any testable trait, whether physical or behavioral, is part of an organism’s phenotype so long as it has a genetic basis. For instance, a scientist may be interested in whether a strain of bacteria can metabolize some sugar, say glucose. One organism that can perform this testable function—ability to metabolize glucose—is positive for the trait (Glu+) and a second that cannot is negative for it (Glu-). Some difference between these organisms’ genotypes determines which phenotypes they exhibit; perhaps a gene in the first produces an enzyme that makes glucose metabolism possible or some genetic sequence in the second changes the timing of a metabolic mechanism. One may, of course, think of these possibilities as phenotypic traits themselves—again, any observable trait with a genetic basis will count as part of the organism’s phenotype. Similarly, in Avida-ED, phenotypic variation depends upon genotypic variations. As in nature, different sequences of instructions in an Avidian’s genome produce whatever different traits it can exhibit, from the performance (or non-performance) of the possible functions of its virtual metabolism to its gestation time, viability and so on. Your goal in this exercise is to look at how changes in genetic sequence can lead to variation of phenotypic functions. -

Glossary in Evolutionary Biology Compiled by Prof

Glossary evolutionary biology. Page 1 Glossary in Evolutionary Biology Compiled by Prof. Dieter Ebert This list contains terms, which a student in evolutionary biology should know. The terms denoted with an * are for an advanced level (Courses in evolutionary and quantitative genetics). This Glossary has been compiled with the help of the following books: • J.R. Krebs & N.B. Davies; An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology. 3. Ed., Blackwell UK. 1993. • S.C. Stearns & R.F. Hoeckstra; Evolution: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2005. • D.A. Roff; The Evolution of life histories. Chapman & Hall. 1992. ____________________________________________________________________ Adaptation: A state that evolved because it improved reproductive performance, to which survival contributes. Also the process that produces that state. Adaptive evolution: The process of change in a population driven by variation in reproductive success that is correlated with heritable variation in a trait. *Additive genetic variance: The part of total genetic variance that can be modelled by allelic effects whose influence on the phenotype in heterozygotes is additive (Additive means that the phenotype of the heterozygote is halfway between the phenotype of the two homozygotes). This part of genetic variance determines the response to selection by quantitative traits. Aging (=Ageing): (See Senescence). Allele: One of the different homologous forms of a single gene; at the molecular level, a different DNA sequence at the same place in the chromosome. Allele frequency: Proportion the copies of a given allele among all alleles at the locus of interest. Allometry: Relationship between the size of two organisms or their parts. E.g. larger organisms produce larger offspring. -

Recitation 4 Slides

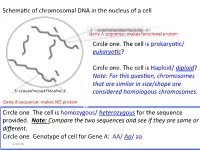

Schema'c of chromosomal DNA in the nucleus of a cell Gene A sequence: makes func'onal protein Circle one. The cell is prokaryo'c/ eukaryo(c? Circle one . The ce ll is Haploid/ diploid? Note: For this ques(on, chromosomes that are similar in size/shape are 5’-CCAGAATACGGATTACGTAC-3’ considered homologous chromosomes. Gene A sequence: makes NO protein Circle one. The cell is homozygous/ heterozygous for the sequence provided. Note: Compare the two sequences and see if they are same or different. Circle one. Genotype of cell for Gene A: AA/ Aa/ aa. 9/24/18 Summary slide Figure 1: The mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see: Marston, A.L., and A. Amon. "Meiosis: cell-cycle controls shuffle and deal." Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology volume 5(2004): 983–997. 9/24/18 Nucleus of a cell ( genotype AaBb) undergoes mitosis. A A A a B B B b DNA Replica'on a a ( S phase) b b Draw the alignment of chromosome during Metaphase Draw the chromosome A a A a and show the B b + B b arrangement of respec've alleles in each daughter cell Daughter cell 1 Daughter cell 2 9/24/18 Cell ( genotype AaBbdd) undergoes NON-disjunc.on during mitosis. A A B B A a a a b b B b DNA Replica'on d d d ( S phase) d d d Draw the alignment of chromosome during Metaphase Draw the chromosome A a and show the A + a B bB b arrangement of d d respec've alleles in d d each daughter cell 9/24/18 Daughter cell 1 Daughter cell 2 Cell ( genotype AaBbdd) undergoes Meiosis A A a a A A a a A a B B b b B B b b B b Replica'on OR D D d d d d D D -

The Unforeseen Challenge: from Genotype-To-Phenotype in Cell Populations

IOP Reports on Progress in Physics Reports on Progress in Physics Rep. Prog. Phys. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78 (2015) 036602 (51pp) doi:10.1088/0034-4885/78/3/036602 78 Review Article 2015 The unforeseen challenge: from © 2015 IOP Publishing Ltd genotype-to-phenotype in cell populations ROP Erez Braun 036602 Department of Physics and Network Biology Research Laboratories, Technion, Haifa 32000, Israel E-mail: [email protected] Received 27 June 2014, revised 4 December 2014 E Braun Accepted for publication 18 December 2014 Published 26 February 2015 Printed in the UK Abstract Biological cells present a paradox, in that they show simultaneous stability and fexibility, ROP allowing them to adapt to new environments and to evolve over time. The emergence of stable cell states depends on genotype-to-phenotype associations, which essentially refect the organization of gene regulatory modes. The view taken here is that cell-state organization is a dynamical 10.1088/0034-4885/78/3/036602 process in which the molecular disorder manifests itself in a macroscopic order. The genome does not determine the ordered cell state; rather, it participates in this process by providing a set of constraints on the spectrum of regulatory modes, analogous to boundary conditions in physical 0034-4885 dynamical systems. We have developed an experimental framework, in which cell populations are exposed to unforeseen challenges; novel perturbations they had not encountered before along their 3 evolutionary history. This approach allows an unbiased view of cell dynamics, uncovering the potential of cells to evolve and develop adapted stable states. In the last decade, our experiments have revealed a coherent set of observations within this framework, painting a picture of the living cell that in many ways is not aligned with the conventional one. -

Cross-Training and Curiosity Interdisciplinarity and an Open Mind

Cross-training and Curiosity Interdisciplinarity and an Open Mind Norman Ellstrand Professor of Genetics UC-Riverside Ph.D years – 1974-1978 Plant Population Genetics + Sex Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte Georges Seurat “He wasn’t talking about botany; he was talking about aaaaaaaaaaaaaag-riculture!” - S. M., March 1978 Applied and Basic Science Silos or a Bridge?… The dilemma Basic research – the grand ivory tower, or angels dancing on the head of a pin? Applied research – dirty or saving the world? UT – to – Duke – to UCR September 1979 Department of “Botany and Plant Sciences” Applied or Basic? Department of “Botany & Plant Sciences”? A brief history 1907 UC Citrus Experiment Station 1954 UC College of Letters & Sciences in Riverside 1960 UCR “General Campus” Department of “Botany & Plant Sciences”? A brief history Separate Departments of Horticulture Agronomy Vegetable Crops “Botanists” in Department of Biology Department of Plant Sciences Mid 1970’s “Department of Botany & Plant Sciences” UCR Basic Applied Paternity Gene flow Plant paternity studies at UCR - 1980’s Rationale – Select small, isolated population – Genotype all plants – Harvest seeds from some plants – Genotype seed – Subtract mother’s contribution – Compare remaining contribution to possible fathers – When you find a match, that’s the father! Basic scientific significance – Precise matching of parents provides information about male fitness, multiple paternity, gender, intermate distance, etc. Who’s the Father? Part 1 Genotype Gene I Gene II Gene -

Genetics, DNA, and Heredity

Genetics, DNA, and Heredity The Basics What is DNA? It's a history book - a narrative of the journey of our species through time. It's a shop manual, with an incredibly detailed blueprint for building every human cell. And it's a transformative textbook of medicine, with insights that will give health care providers immense new powers to treat, prevent and cure disease." - Francis Collins What Does DNA Look Like? A T G C Every cell in our body has the same DNA…. Eye cell Karyotype Lung cell Toe cell How much DNA is in one cell? Genome = 46 chromosomes Genome = approx. 3 billion base pairs One base pair is 0.00000000034 meters DNA sequence in any two people is 99.9% identical – only 0.1% is unique! What makes one cell different from another? DNA = “the life instructions of the cell” Gene = segment of DNA that tells the cell how to make a certain protein. Allele = one of two or more different versions of a gene Sequence for normal adult hemoglobin: Sequence for mutant hemoglobin: Wild-type Hemoglobin Protein Mutant Protein Normal Red Blood Cell Abnormal Red Blood Cell The Human Genome Project Goals • To sequence (i.e. determine the exact order of nucleotides (A,T,G,C) for ALL of the DNA in a human cell • To determine which sections of DNA represent individual genes (protein-coding units). The HGP: International effort to decipher the blueprint of a human being. How It Was Done Samples sent to Human Genome DNA samples collected from Project centers across the world thousands of volunteers Scientists at centers perform DNA sequencing and analysis • February 2001: Draft of the sequence published in Nature (public effort )and Science (Celera – private company). -

Human Genome Variation and the Concept of Genotype Networks Dall'olio Giovanni Marco1, Bertranpetit Jaume1, Wagner Andreas2,3,4, Laayouni Hafid1

Human Genome Variation and the concept of Genotype Networks Dall'Olio Giovanni Marco1, Bertranpetit Jaume1, Wagner Andreas2,3,4, Laayouni Hafid1 1 Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), 08003 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain 2 Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich. 3 The Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Bioinformatics, Quartier Sorge, Batiment Genopode, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 4 The Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA Page: 1 / 31 Abstract Genotype networks are a method used in systems biology to study the “innovability” of a set of genotypes having the same phenotype. In the past they have been applied to determine the genetic heterogeneity, and stability to mutations, of systems such as metabolic networks and RNA folds. Recently, they have been the base for re-conciliating the two neutralist and selectionist schools on evolution. Here, we adapted the concept of genotype networks to the study of population genetics data, applying them to the 1000 Genomes dataset. We used networks composed of short haplotypes of Single Nucleotide Variants (SNV), and defined phenotypes as the presence or absence of a haplotype in a human population. We used coalescent simulations to determine if the number of samples in the 1000 Genomes dataset is large enough to represent the genetic variation of real populations. The result is a scan of how properties related to the genetic heterogeneity and stability to mutations are distributed along the human genome. We found that genes involved in acquired immunity, such as some HLA and MHC genes, tend to have the most heterogeneous and connected networks; and we have also found that there is a small, but significant difference between networks of coding regions and those of non-coding regions, suggesting that coding regions are both richer in genotype diversity, and more stable to mutations.