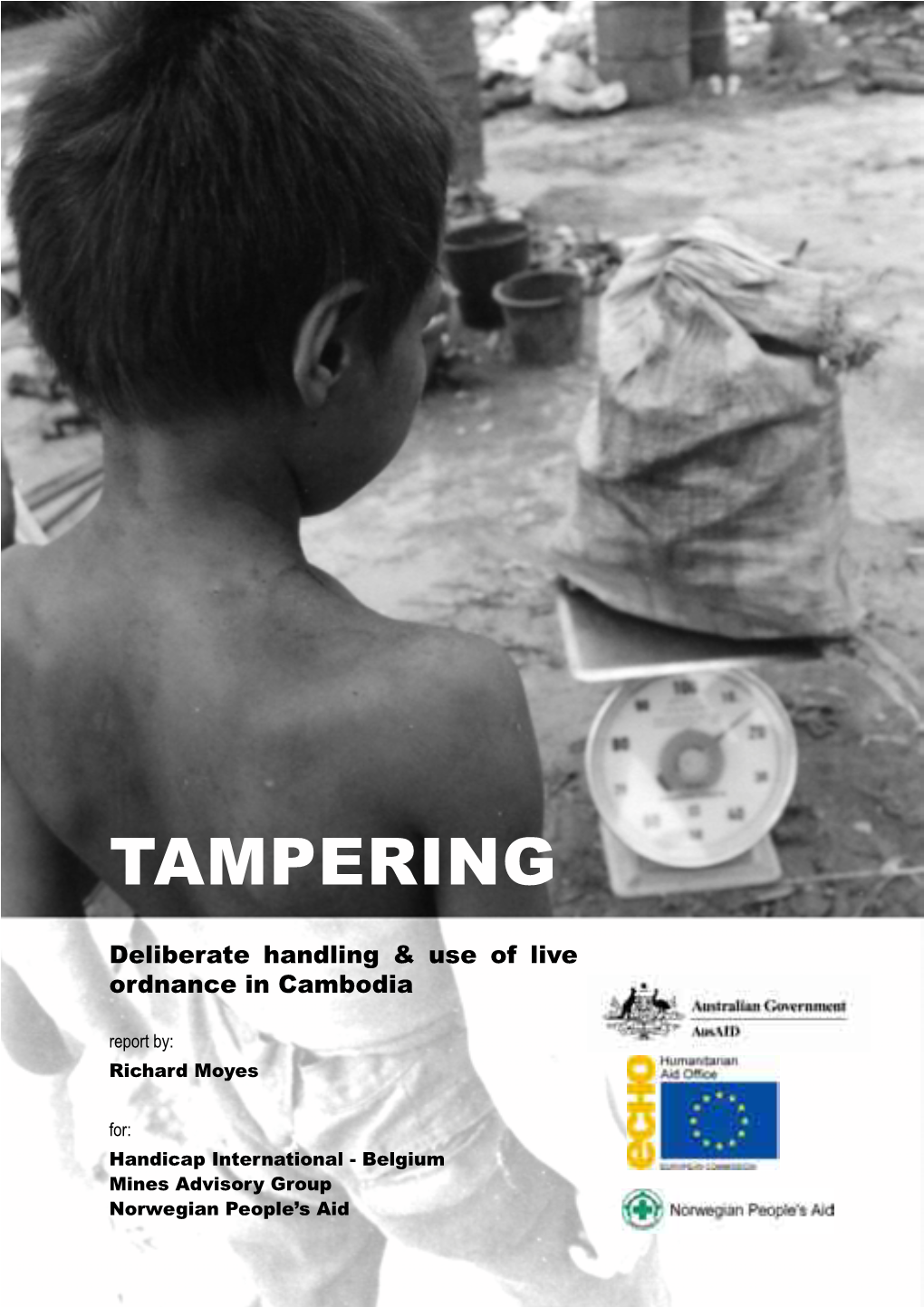

Tampering: Deliberate Handling & Use of Live Ordnance in Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Administration and Reform Project Mid-Term Evaluation

Local Administration and Reform Project Mid-Term Evaluation March – May 2009 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared under USAID/Cambodia—Checchi and Company Consulting, Inc. Contract GS-10F-0425M, Order No. 442-M-00-07-00009-00. The report was authored by Michael Calavan (Team Leader), Ashley Barr and Harry Blair. Cambodia MSME Evaluation Page ii Local Administration and Reform Project Mid-Term Evaluation DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Table of Contents ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................. ii MAP OF CAMBODIA..................................................................................................................iii 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 1 2. CONTEXT.................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Cambodia’s political and social situation ............................................................................. 4 2.2 USAID/Cambodia’s Strengthening Governance and Accountability Program.................... 5 3. THE LOCAL ADMINISTRATION AND REFORM PROJECT.............................................. 6 3.1 USAID’s -

CAMBODIA FOOD PRICE and WAGE BULLETIN Agricultural Marketing November 2013, Issue 57 Office, DPS, MAFF

ព្រឹត្តិបព្ត្䏒លៃ讶莶រ និងព្ាក់⏒ួលន រលក插មនៅក插ុពᾶ CAMBODIA FOOD PRICE AND WAGE BULLETIN Agricultural Marketing November 2013, Issue 57 Office, DPS, MAFF HIGHLIGHTS Food purchasing power of households decreased in rural areas by 4.8% and increased by 9.1% in urban areas on a month-on-month basis. Retail price of lowest quality rice in rural and urban areas decreased by 0.8% and 4.0% on a month-on-month basis, respectively. Wholesale price of mixed rice decreased by 2.0% month-on-month and by 9.3% on a year-on-year basis. The Inflation Rate was 4.2% in October. Month-on-month food prices increased by 0.2% while gasoline prices remained stable. FAO Food Price Index averaged 206.3 points, a month-on-month increase of 0.2%; it remained almost unchanged due to stable meat and dairy prices. Thai and Vietnamese Export price of rice: Thai rice prices decreased by 5.2% while Vietnamese rice prices increased by 3.6% on a month- on-month basis. Overview CONTENT 1 This Bulletin is a joint publication by the Agricultural Marketing Overview...................................................................................................... 1 Office (Department of Planning and Statistics) of the Ministry of International Food and Rice Prices .................................................... 1 Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (AMO MAFF) and the United Regional Rice Wholesale Prices ........................................................... 1 Nations World Food Programme Cambodia. It monitors the price of Cambodia Consumer Price Index (CPI) ............................................. 2 food commodities and wage rates of unskilled labor on a monthly basis. It also aims to detect changes and identify trends in the food Local Food Commodity Prices ............................................................. -

Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017

〔AREIPGR Vol. 34 : 102-117, 2018〕 doi:10.24514/00001134 Original Paper Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017 Hiroshi MATSUNAGA 1), Makoto YOKOTA 2), Mat LEAKHENA 3), Sakhan SOPHANY 3) 1) Institute of Vegetable and Floriculture Science, NARO, Kusawa 360, Ano, Tsu, Mie 514-2392, Japan 2) Kochi Agriculture Research Center, 1100, Hataeda, Nangoku, Kochi 783-0023, Japan 3) Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, National Road 3, Prateahlang, Dangkor, P. O. Box 01, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Communicated by K. FUKUI (Genetic Resources Center, NARO) Received Nov. 1, 2018, Accepted Dec. 14, 2018 Corresponding author: H. MATSUNAGA (Email: [email protected]) Summary The National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) and the Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI) have collaborated since 2014 under the Plant Genetic Resources in Asia (PGRAsia) project to survey the vegetable genetic resources available in Cambodia. As part of this project, three field surveys of Solanaceae crops were conducted in November 2014, 2015 and 2016 in western, eastern and northern Cambodia, respectively. In November 2017, we conducted a fourth field survey in southern Cambodia, including the Svay Rieng, Prey Veng, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Kou Kong, Sihanoukville, Kampot and Takeo provinces. We collected 56 chili pepper (20 Capsicum annuum, 36 C. frutescens) and 4 eggplant (4 Solanum spp.) fruit samples from markets, farmers’ yards, farmers’ fields and an open space. After harvesting seeds from the collected fruits, the seeds were divided equally and half were conserved in the CARDI and the other half were transferred to the Genetic Resource Center, NARO using the standard material transfer agreement (SMTA). -

Grid Reinforcement Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 53324-001 August 2020 Proposed Loan and Administration of Grants Kingdom of Cambodia: Grid Reinforcement Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 July 2020) Currency unit – riel/s (KR) KR1.00 = $0.00024 $1.00 = KR4,096 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BESS – battery energy storage system CEF – Clean Energy Fund COVID-19 – coronavirus disease EDC – Electricité du Cambodge EMP – environmental management plan LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan MME Ministry of Mines and Energy PAM – project administration manual SCF – Strategic Climate Fund TA – technical assistance WEIGHTS AND MEASURES GWh – gigawatt-hour ha – hectare km – kilometer kV – kilovolt kWh – kilowatt-hour MW – megawatt GLOSSARY Congestion relief – Benefit of using battery energy storage system by covering peak loads exceeding the load carrying capacity of an existing transmission and distribution equipment Curtailment reserve – The capacity to provide power output in a given amount of time during power shortcuts and shortages Output smoothing – The process of smoothing power output to provide more stability and reliability of fluctuating energy sources Primary frequency – A crucial system which fixes the effects of power imbalance response between electricity -

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit and Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT AND REGIONAL BUREAU FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Reintegration programmes for refugees in South-East Asia Lessons learned from UNHCR’s experience By Brett Ballard EPAU/2002/01 April 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation and relevance. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province

Project Number: 46009-001 October 2012 Cambodia: Flood Damage Emergency Reconstruction Project Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province Prepared by: Ministry of Rural Development By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographical area, or by using the term "country" in the website, ADB does not intend to make any judgment as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Boundaries, colors, denominations or any other information shown on maps do not imply, on the part of ADB, any judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries, colors, denominations, or information. Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province 480000 487500 495000 502500 510000 517500 525000 532500 540000 547500 555000 562500 570000 577500 585000 592500 600000 607500 615000 622500 630000 637500 645000 652500 660000 m Tho 1375000 g 1375000 pon #0 Legend Kam #0 Tuol Sambuor #0 Ou Mlu Ta Prok #0 #0 Flood Damaged Rural Road 1367500 1367500 Dang Kdar Areaks Tnaot #0 #0 Cheyyou National Roads Chamkar Andoung Lvea Leu #0#0 2 1$ Spueu 2 2 tu K #0 #0 Krouch#0 Chhmar#0 Preah Andoung ra Ckhum 1360000 Chamkar#0 Leu t 1360000 Me Sar Chrey #0 1$Peam Kaoh#0 Sna #0 ie Svay Teab Krouch Chhmar #0 Preaek Kak #0 Khpob Ta Nguon Roka Khnaor 1$ Csrok Soupheas 1$ Svay Khleang#0 2 #0 #0 #0C #0 1 K tu7#0 Stueng TrangTrea Peus Pir UV Chumnik Peus Muoy .! Ckhet 1352500 1352500 Ta Ong #0 Tuol Preah Khleang #0 #0 Water way #0 Preaek Bak #0 #0 Preaek a Chi Sampong -

For: Review Kingdom of Cambodia Country Strategy and Programme Evaluation

Document: EC 2018/100/W.P.2/Rev.1 Agenda: 3 Date: 23 Feburary 2018 E Distribution: Public Original: English Kingdom of Cambodia Country strategy and programme evaluation Note to Evaluation Committee members Focal points: Technical questions: Dispatch of documentation: Oscar A. Garcia Alessandra Zusi Bergés Director Senior Governing Bodies Officer Independent Office of Evaluation of IFAD Governing Bodies Tel.: +39 06 5459 2274 Tel.: +39 06 5459 2092 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Fumiko Nakai Senior Evaluation Officer Tel.: +39 06 5459 2283 e-mail: [email protected] Evaluation Committee — 100th Session Rome, 23 March 2018 For: Review EC 2018/100/W.P.2/Rev.1 Contents Executive summary ii Appendix I. Agreement at Completion Point 1 II. Main report Kingdom of Cambodia – Country strategy and programme evaluation 7 i EC 2018/100/W.P.2/Rev.1 Executive summary A. Background 1. In 2017, the Independent Office of Evaluation of IFAD (IOE) undertook the first country strategy and programme evaluation (CSPE) for the Kingdom of Cambodia. The CSPE reviewed the evolution of the strategy, results and performance of the partnership between IFAD and the Royal Government of Cambodia since the Fund started operations in 1997, but with a focus on the last decade, particularly with respect to the investment portfolio. The CSPE covers the investment portfolio (seven projects that were approved between 2000 and 2016), complementary (non-lending) activities (knowledge management, partnership-building and policy dialogue, including grants), as well as country programme strategy and management. 2. Objectives. The CSPE had two main objectives: (i) to assess the results and performance of the IFAD-financed strategy and programme; and (ii) to generate findings and recommendations for the future partnership between IFAD and the RoyalGovernment of Cambodia for enhanced development effectiveness and rural poverty eradication. -

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia Code of Province / Municipality and District 01 BANTEAY MEANCHEY 08 KANDAL 16 RATANAK KIRI 1608 0102 Mongkol Borei 0801 Kandal Stueng 1601 Andoung Meas 2204 0103 Phnum Srok 0802 Kien Svay 1602 Krong Ban Lung 1903 0104 Preah Netr Preah 0803 Khsach Kandal 1603 Bar Kaev 2202 2205 1303 2201 0105 Ou Chrov 0804 Kaoh Thum 1604 Koun Mom 1609 0106 Krong Serei Saophoan 0805 Leuk Daek 1605 Lumphat 0107 2203 0107 Thma Puok 0806 Lvea Aem 1606 Ou Chum 0108 Svay Chek 0807 Mukh Kampul 1607 Ou Ya Dav 1302 1601 0109 Malai 0808 Angk Snuol 1608 Ta Veaeng 1307 0110 Krong Paoy Paet 0809 Ponhea Lueu 1609 Veun Sai 0103 1714 1606 0108 1712 0810 S'ang 1304 1904 02 BATTAMBANG 0811 Krong Ta Khmau 17 SIEM REAP 1308 0201 Banan 1701 Angkor Chum 1701 1602 1603 1713 1905 0202 Thma Koul 09 KOH KONG 1702 Angkor Thum 0110 0105 1901 0203 Krong Battambang 0901 Botum Sakor 1703 Banteay Srei 0106 0104 1706 1702 1703 1301 1607 0204 Bavel 0902 Kiri Sakor 1704 Chi Kraeng 0109 1604 0205 Aek Phnum 0903 Kaoh Kong 1706 Kralanh 0102 1707 1306 1605 0206 Moung Ruessei 0904 Krong Khemarak Phoumin 1707 Puok 0210 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0905 Mondol Seima 1709 Prasat Bakong 1710 1305 0208 Sangkae 0906 Srae Ambel 1710 Krong Siem Reab 0211 1709 0209 Samlout 0907 Thma Bang 1711 Soutr Nikom 0202 0205 0204 1711 1902 0210 Sampov Lun 1712 Srei Snam 1704 0211 Phnom Proek 10 KRATIE 1713 Svay Leu 0212 0203 0212 Kamrieng 1001 Chhloung 1714 Varin 0213 Koas Krala 1002 Krong Kracheh 0208 0604 0606 1102 0214 Rukhak Kiri 1003 Preaek Prasab 18 PREAH SIHANOUK -

Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience

Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 104 Vol. 5 No.2 February 2018: 104-126 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2018.5.2.104 Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience Rem Samnang Hay Chanthol1 Faculty of Sociology and Community Development, University of Battambang, Cambodia Abstract As the second most populous province in Cambodia, Battambang also exhibits an increasing number of urban poor areas. This research focuses on the economic situation of slum areas in Battambang and how people in slum areas are affected by climate change. This research report describes socioeconomics of people living in slum areas in 4 villages in Battambang City. An investigation will be made on motivation of moving to slum areas, access to water, access to sanitation, access to electricity, transport and delivery, access to health care, access to education, security of tenure, cost of living in slum, literacy, and access to finance. We also explore the policy of the public sector toward climate change in Cambodia. Keywords: slum, climate change, climate resilience, poverty 1 All correspondence concerning to this paper should be addressed to Hay Chantol at the University of Battambang, National Road 5, Sangkat Preaek Preah Sdach, Battambang City, Battambang Province, Cambodia or by email at [email protected]. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 105 Vol. 5 No.2 February 2018: 104-126 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2018.5.2.104 Introduction Battambang is a rice bowl of Cambodia. The total rice production in the province accounted for 8.5% of the total rice production of 9.3 million tons in 2013. -

Buddhist Policy Chart of Witness Evidence from Each

ERN>01462446</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC ANNEX E BUDDHIST POLICY CHART OF WITNESS EVIDENCE FROM EACH DK ZONE TABLE OF CONTENTS Southwest Zone [SWZ] 2 East Zone [EZ] 12 Sector 505 Kratie [505S] 21 Sector 105 Mondulkiri [105S] 24 Northeast Zone [NEZ] 26 North Zone [NZ] 28 Northwest Zone [NWZ] 36 West Zone [WZ] 43 Phnom Penh Special Zone Phnom Penh Autonomous Municipality [PPSZ PPAM] 45 ’ Co Prosecutors Closing Brief in Case 002 02 Annex E Page 1 of 49 ERN>01462447</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC SOUTHWEST ZONE [SWZ] Southwest Zone No Name Quote Source Sector 25 Koh Thom District Chheu Khmau Pagoda “But as in the case of my family El 170 1 Pin Pin because we were — we had a lot of family members then we were asked to live in a monk Yathay T 7 Feb 1 ” Yathay residence which was pretty large in that pagoda 2013 10 59 34 11 01 21 Sector 25 Kien Svay District Kandal Province “In the Pol Pot s time there were no sermon El 463 1 Sou preached by monks and there were no wedding procession We were given with the black Sotheavy T 24 Sou ” 2 clothing black rubber sandals and scarves and we were forced Aug 2016 Sotheavy 13 43 45 13 44 35 Sector 25 Koh Thom District Preaek Ph ’av Pagoda “I reached Preaek Ph av and I saw a lot El 197 1 Sou of dead bodies including the corpses of the monks I spent overnight with these corpses A lot Sotheavy T 27 of people were sick Some got wounded they cried in pain I was terrified ”—“I was too May 2013 scared to continue walking when seeing these -

List of Provinces, Ods, Health Facilities

Impact Evaluation of Service Delivery Grants Public Disclosure Authorized to Improve Quality of Health Care Delivery in Cambodia Baseline Study Report Public Disclosure Authorized Somil Nagpal, Sebastian Bauhoff, Kayla Song, Theepakorn Jithitikulchai, Sreytouch Vong, Manveen Kohli April 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This baseline report was a mammoth undertaking. The H-EQIP pooled fund partners and the study authors sincerely acknowledge the support, guidance, inputs and insights received from several institutions and individuals, without whom this study would not have been possible. Our gratitude commences with immense appreciation and kind thanks to the Royal Government of Cambodia team, particularly the project management of H-EQIP (H.E. Prof. Eng Huot, H.E. Dr. Yuok Sambath and Dr. Lo Veasnakiry) as well as all the heads and officials of provincial health departments, operational district offices, and health centers that supported this study. Mr. Khun Vibol provided very valuable coordination support which is deeply acknowledged. Continued support of Australian Aid, German Development Cooperation (through KfW) and KOICA as H- EQIP pooled fund partners with World Bank, jointly provided the financial resources to undertake this impact evaluation. Financial support from KOICA for the baseline survey costs helped commence the baseline effort even before the pooled TA funding mechanism for H-EQIP was set up. Priya Agarwal- Harding closely supported the pooled fund partners’ coordination efforts and her support is gratefully recognized. Sebastian Bauhoff (now at Harvard School of Public Health and then with the Centre for Global Development) provided technical leadership for the research team in the survey design, sampling methodology and data analysis. -

Ysssbf

ERN>01620233</ERN> D384 2 ANNEX ~ LIST OF CIVIL PARTY APPLICATIONS INADMISSIBLE 3|b SifIffe Full Name Reasons for Inadmissibility Finding Province Foreign Lawyer Isis \b 2 The Applicant described the following enslavement and OIA at various locations murder of her father and s I uncle s family in Siem Reap Province While it is recognised that these are traumatising events they do not UTH Rathana }tctf Banteay Meanchey 5 Chet Vanly S relate to any matter which would permit the admission of the Applicant to be joined as a civil party as they fall a Q Sr 5 outside of the territorial scope of the Case File ~~ n 3 The Applicant described being ordered to carry out hard labour from 1975 onwards including at Trapeang 23 ru I Thma Dam However her identification document confirmed in the information entered in her VIF state that 02 CHEN Savey she was bom in 1974 and was thus an infant in 1975 While this is traumatising these inconsistencies make it Banteay Meanchey s Chet Vanly s 02 ~ to deduce that it is more than not to be true that she suffered as a of one of the 3 ~~ impossible likely consequence crimes ~~ charged n 3 s ¦02 The Applicant s VIF and Supplementary Information are contradictory The Applicant was not sent to 3 a Khnol Security Centre He was a RAK soldier throughout DK While he witnessed various crimes and NHOEK Yun c Banteay Meanchey 5 Chet Vanly S numerous members of his family died during the Regime it is not established that it is more likely than not to b 3 Q £ a true that the Applicant suffered as a result of one of the crimes