Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMBODIA FOOD PRICE and WAGE BULLETIN Agricultural Marketing November 2013, Issue 57 Office, DPS, MAFF

ព្រឹត្តិបព្ត្䏒លៃ讶莶រ និងព្ាក់⏒ួលន រលក插មនៅក插ុពᾶ CAMBODIA FOOD PRICE AND WAGE BULLETIN Agricultural Marketing November 2013, Issue 57 Office, DPS, MAFF HIGHLIGHTS Food purchasing power of households decreased in rural areas by 4.8% and increased by 9.1% in urban areas on a month-on-month basis. Retail price of lowest quality rice in rural and urban areas decreased by 0.8% and 4.0% on a month-on-month basis, respectively. Wholesale price of mixed rice decreased by 2.0% month-on-month and by 9.3% on a year-on-year basis. The Inflation Rate was 4.2% in October. Month-on-month food prices increased by 0.2% while gasoline prices remained stable. FAO Food Price Index averaged 206.3 points, a month-on-month increase of 0.2%; it remained almost unchanged due to stable meat and dairy prices. Thai and Vietnamese Export price of rice: Thai rice prices decreased by 5.2% while Vietnamese rice prices increased by 3.6% on a month- on-month basis. Overview CONTENT 1 This Bulletin is a joint publication by the Agricultural Marketing Overview...................................................................................................... 1 Office (Department of Planning and Statistics) of the Ministry of International Food and Rice Prices .................................................... 1 Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (AMO MAFF) and the United Regional Rice Wholesale Prices ........................................................... 1 Nations World Food Programme Cambodia. It monitors the price of Cambodia Consumer Price Index (CPI) ............................................. 2 food commodities and wage rates of unskilled labor on a monthly basis. It also aims to detect changes and identify trends in the food Local Food Commodity Prices ............................................................. -

Ggácmnmucrmhvisambaøkñú

01116406 F1/3.1 ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįО ď ďijЊ ⅜₤Ĝ ŪĮйņΉ˝℮Ūij GgÁCMnMuCRmHvisamBaØkñúgtulakarkm <úCa Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Royaume du Cambodge Chambres Extraordinaires au sein des Tribunaux Cambodgiens Nation Religion Roi Β₣ðĄеĕНеĄŪņйijНŵŁũ˝еĮРŲ Supreme Court Chamber Chambre de la Cour suprême TRANSCRIPT OF APPEAL PROCEEDINGS PUBLIC Case File Nº 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SC 6 July 2015 Before the Judges: KONG Srim, Presiding The Accused: NUON Chea Ya Narin KHIEU Samphan Agnieszka KLONOWIECKA-MILART SOM Sereyvuth Chandra Nihal JAYASINGHE Lawyers for the Accused: MONG Monichariya Victor KOPPE Florence N. MWACHANDE-MUMBA LIV Sovanna SON Arun KONG Sam Onn Trial Chamber Greffiers/Legal Officers: Arthur VERCKEN Volker NERLICH SEA Mao Sheila PAYLAN Lawyers for the Civil Parties: Paolo LOBBA Marie GUIRAUD PHAN Thoeun HONG Kimsuon SIN Soworn TY Srinna For the Office of the Co-Prosecutors: VEN Pov Nicholas KOUMJIAN SONG Chorvoin For Court Management Section: UCH Arun 01116407 F1/3.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Supreme Court Chamber – Appeal Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SC 06/07/2015 I N D E X Mr. TOIT Thoeurn (SCW-5) Questioning by The President KONG Srim ......................................................................................... page 2 Questioning by Mr. KOPPE .................................................................................................................. page 6 Questioning by Mr. VERCKEN .......................................................................................................... -

Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017

〔AREIPGR Vol. 34 : 102-117, 2018〕 doi:10.24514/00001134 Original Paper Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017 Hiroshi MATSUNAGA 1), Makoto YOKOTA 2), Mat LEAKHENA 3), Sakhan SOPHANY 3) 1) Institute of Vegetable and Floriculture Science, NARO, Kusawa 360, Ano, Tsu, Mie 514-2392, Japan 2) Kochi Agriculture Research Center, 1100, Hataeda, Nangoku, Kochi 783-0023, Japan 3) Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, National Road 3, Prateahlang, Dangkor, P. O. Box 01, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Communicated by K. FUKUI (Genetic Resources Center, NARO) Received Nov. 1, 2018, Accepted Dec. 14, 2018 Corresponding author: H. MATSUNAGA (Email: [email protected]) Summary The National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) and the Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI) have collaborated since 2014 under the Plant Genetic Resources in Asia (PGRAsia) project to survey the vegetable genetic resources available in Cambodia. As part of this project, three field surveys of Solanaceae crops were conducted in November 2014, 2015 and 2016 in western, eastern and northern Cambodia, respectively. In November 2017, we conducted a fourth field survey in southern Cambodia, including the Svay Rieng, Prey Veng, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Kou Kong, Sihanoukville, Kampot and Takeo provinces. We collected 56 chili pepper (20 Capsicum annuum, 36 C. frutescens) and 4 eggplant (4 Solanum spp.) fruit samples from markets, farmers’ yards, farmers’ fields and an open space. After harvesting seeds from the collected fruits, the seeds were divided equally and half were conserved in the CARDI and the other half were transferred to the Genetic Resource Center, NARO using the standard material transfer agreement (SMTA). -

Grid Reinforcement Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 53324-001 August 2020 Proposed Loan and Administration of Grants Kingdom of Cambodia: Grid Reinforcement Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 July 2020) Currency unit – riel/s (KR) KR1.00 = $0.00024 $1.00 = KR4,096 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BESS – battery energy storage system CEF – Clean Energy Fund COVID-19 – coronavirus disease EDC – Electricité du Cambodge EMP – environmental management plan LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan MME Ministry of Mines and Energy PAM – project administration manual SCF – Strategic Climate Fund TA – technical assistance WEIGHTS AND MEASURES GWh – gigawatt-hour ha – hectare km – kilometer kV – kilovolt kWh – kilowatt-hour MW – megawatt GLOSSARY Congestion relief – Benefit of using battery energy storage system by covering peak loads exceeding the load carrying capacity of an existing transmission and distribution equipment Curtailment reserve – The capacity to provide power output in a given amount of time during power shortcuts and shortages Output smoothing – The process of smoothing power output to provide more stability and reliability of fluctuating energy sources Primary frequency – A crucial system which fixes the effects of power imbalance response between electricity -

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit and Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT AND REGIONAL BUREAU FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Reintegration programmes for refugees in South-East Asia Lessons learned from UNHCR’s experience By Brett Ballard EPAU/2002/01 April 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation and relevance. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province

Project Number: 46009-001 October 2012 Cambodia: Flood Damage Emergency Reconstruction Project Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province Prepared by: Ministry of Rural Development By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographical area, or by using the term "country" in the website, ADB does not intend to make any judgment as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Boundaries, colors, denominations or any other information shown on maps do not imply, on the part of ADB, any judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries, colors, denominations, or information. Location Map of Flood Damaged Rural Roads in Kampong Cham Province 480000 487500 495000 502500 510000 517500 525000 532500 540000 547500 555000 562500 570000 577500 585000 592500 600000 607500 615000 622500 630000 637500 645000 652500 660000 m Tho 1375000 g 1375000 pon #0 Legend Kam #0 Tuol Sambuor #0 Ou Mlu Ta Prok #0 #0 Flood Damaged Rural Road 1367500 1367500 Dang Kdar Areaks Tnaot #0 #0 Cheyyou National Roads Chamkar Andoung Lvea Leu #0#0 2 1$ Spueu 2 2 tu K #0 #0 Krouch#0 Chhmar#0 Preah Andoung ra Ckhum 1360000 Chamkar#0 Leu t 1360000 Me Sar Chrey #0 1$Peam Kaoh#0 Sna #0 ie Svay Teab Krouch Chhmar #0 Preaek Kak #0 Khpob Ta Nguon Roka Khnaor 1$ Csrok Soupheas 1$ Svay Khleang#0 2 #0 #0 #0C #0 1 K tu7#0 Stueng TrangTrea Peus Pir UV Chumnik Peus Muoy .! Ckhet 1352500 1352500 Ta Ong #0 Tuol Preah Khleang #0 #0 Water way #0 Preaek Bak #0 #0 Preaek a Chi Sampong -

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia Code of Province / Municipality and District 01 BANTEAY MEANCHEY 08 KANDAL 16 RATANAK KIRI 1608 0102 Mongkol Borei 0801 Kandal Stueng 1601 Andoung Meas 2204 0103 Phnum Srok 0802 Kien Svay 1602 Krong Ban Lung 1903 0104 Preah Netr Preah 0803 Khsach Kandal 1603 Bar Kaev 2202 2205 1303 2201 0105 Ou Chrov 0804 Kaoh Thum 1604 Koun Mom 1609 0106 Krong Serei Saophoan 0805 Leuk Daek 1605 Lumphat 0107 2203 0107 Thma Puok 0806 Lvea Aem 1606 Ou Chum 0108 Svay Chek 0807 Mukh Kampul 1607 Ou Ya Dav 1302 1601 0109 Malai 0808 Angk Snuol 1608 Ta Veaeng 1307 0110 Krong Paoy Paet 0809 Ponhea Lueu 1609 Veun Sai 0103 1714 1606 0108 1712 0810 S'ang 1304 1904 02 BATTAMBANG 0811 Krong Ta Khmau 17 SIEM REAP 1308 0201 Banan 1701 Angkor Chum 1701 1602 1603 1713 1905 0202 Thma Koul 09 KOH KONG 1702 Angkor Thum 0110 0105 1901 0203 Krong Battambang 0901 Botum Sakor 1703 Banteay Srei 0106 0104 1706 1702 1703 1301 1607 0204 Bavel 0902 Kiri Sakor 1704 Chi Kraeng 0109 1604 0205 Aek Phnum 0903 Kaoh Kong 1706 Kralanh 0102 1707 1306 1605 0206 Moung Ruessei 0904 Krong Khemarak Phoumin 1707 Puok 0210 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0905 Mondol Seima 1709 Prasat Bakong 1710 1305 0208 Sangkae 0906 Srae Ambel 1710 Krong Siem Reab 0211 1709 0209 Samlout 0907 Thma Bang 1711 Soutr Nikom 0202 0205 0204 1711 1902 0210 Sampov Lun 1712 Srei Snam 1704 0211 Phnom Proek 10 KRATIE 1713 Svay Leu 0212 0203 0212 Kamrieng 1001 Chhloung 1714 Varin 0213 Koas Krala 1002 Krong Kracheh 0208 0604 0606 1102 0214 Rukhak Kiri 1003 Preaek Prasab 18 PREAH SIHANOUK -

List of Provinces, Ods, Health Facilities

Impact Evaluation of Service Delivery Grants Public Disclosure Authorized to Improve Quality of Health Care Delivery in Cambodia Baseline Study Report Public Disclosure Authorized Somil Nagpal, Sebastian Bauhoff, Kayla Song, Theepakorn Jithitikulchai, Sreytouch Vong, Manveen Kohli April 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This baseline report was a mammoth undertaking. The H-EQIP pooled fund partners and the study authors sincerely acknowledge the support, guidance, inputs and insights received from several institutions and individuals, without whom this study would not have been possible. Our gratitude commences with immense appreciation and kind thanks to the Royal Government of Cambodia team, particularly the project management of H-EQIP (H.E. Prof. Eng Huot, H.E. Dr. Yuok Sambath and Dr. Lo Veasnakiry) as well as all the heads and officials of provincial health departments, operational district offices, and health centers that supported this study. Mr. Khun Vibol provided very valuable coordination support which is deeply acknowledged. Continued support of Australian Aid, German Development Cooperation (through KfW) and KOICA as H- EQIP pooled fund partners with World Bank, jointly provided the financial resources to undertake this impact evaluation. Financial support from KOICA for the baseline survey costs helped commence the baseline effort even before the pooled TA funding mechanism for H-EQIP was set up. Priya Agarwal- Harding closely supported the pooled fund partners’ coordination efforts and her support is gratefully recognized. Sebastian Bauhoff (now at Harvard School of Public Health and then with the Centre for Global Development) provided technical leadership for the research team in the survey design, sampling methodology and data analysis. -

Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia

Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER I608-P Prepared in cooperation with the ^<ryr>s. Government of Cambodia under the t auspices of the United States Agency rf for International Development \ Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia By W. C. RASMUSSEN and G. M. BRADFORD CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF ASIA AND OCEANIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-P Prepared in cooperation with the Government of Cambodia under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1977 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Rasmussen, William Charles, 1917-73 Ground-water resources of Cambodia. (Geological Survey water-supply paper; 1608-P: Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania) "Prepared in cooperation with the Govern ment of Cambodia under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development." 1. Water, Underground Cambodia. I. Bradford, G. M., joint author. II. Cambodia. III. United States. Agency for International Development. IV. Title. V. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Water-supply paper ; 1608-P. VI. Series: Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania. TC801.U2 no. 1608-P [GB1144.C3] 627'.08s [553'.79'09596] 74-20781 For sale by the Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey, 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract __________________________________________ -

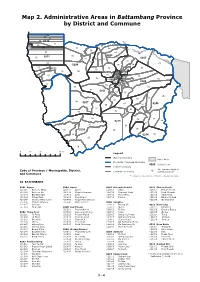

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 05 0202 05 0211 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

Department of Potable Water Supply, Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy Kingdom of Cambodia

DEPARTMENT OF POTABLE WATER SUPPLY, MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY, MINES AND ENERGY KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE PROJECT ON ADDITIONAL NEW WATER TREATMENT PLANTS FOR KAMPONG CHAM AND BATTAMBANG WATERWORKS IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NIHON SUIDO CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. WATER AND SEWER BUREAU, CITY OF KITAKYUSHU CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. Summary 1. Overview of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1) Natural Condition The total landmass of the Kingdom of Cambodia (hereinafter referred to as Cambodia) is approximately 181,000 km2 (a little less than the half of Japan’s total area). The Mekong River traverses the country from north to south, crossing the boundary with Lao PDR in the north. The Tonle Sap Lake and the river systems are the dominant features forming the Central Plains which cover three quarters of the country’s area. The Tonle Sap River runs off the Tonle Sap Lake and joins together with the Mekong River at the capital city of Phnom Penh. To the north and northeast, near the boundaries with Viet Nam and Lao PDR, are mountain ranges with dense virgin forests and diverse wildlife. According to the 2008 census, Cambodia has an estimated population of 1,340,000 people. Cambodia, lying entirely within the tropics, has a hot and humid climate, which is divided into wet (June to October) and dry (November to May) seasons. Severe heat occurs especially in the second half of the dry season (February to May) and the day time temperature can rise up to 30 to 40 ℃. -

Address of ACLEDA Bank Plc.

Address of ACLEDA Bank Plc. NO. OFFICE NAME OFFICE TYPE ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL VARIATION 1 HEADQUARTERS HQ (OPD) #61, Preah Monivong Blvd., Sangkat Srah Chork, Tel: (855) 23 430 999 / 998 777 (OPERATION DIVISION) Khan Daun Penh, Phnom Penh. Fax: (855) 23 430 555 / 998 666 P.O. Box: 1149 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.acledabank.com.kh SWIFT Code: ACLBKHPP For Customer Inquiry Call: Tel: (855) 23 994 444 (855) 15 999 233 E-mail: [email protected] OPERATION DIVISION Tel: (855) 23 998 357 Fax: (855) 15 900 444 E-mail: [email protected] 2 SIEM REAP PB #1,2,3 & 4 , Sivatha Street, Phum Mondul 2 , Tel: (855) 63 963 251 / 660 Sangkat Svay Dangkum, Krong Siem Reap, (855) 15 900 396 Siem Reap Province. Fax: (855) 63 963 280 / 63 966 070 P.O. Box: 1149 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.acledabank.com.kh SWIFT Code: ACLBKHPP 3 BANTEAY SREI DISTRICT DBC Group 5, Banteay Srei Village, Khnar Sanday Commune, Tel: (855) 15 900 164 BRANCH-KHNAR SANDAY Banteay Srei District, Siem Reap Province. Fax: (855) 63 963 280 / 63 966 070 E-mail: [email protected] COMMUNE 4 BANTEAY SREI DISTRICT DBC Group 10, Preah Dak Village, Preah Dak Commune, Tel: (855) 15 600 246 BRANCH-PREAH DAK COMMUNE Banteay Srei District, Siem Reap Province. Fax: (855) 63 963 280 / 63 966 070 E-mail: [email protected] 5 BANTEAY MEANCHEY PB Group 3, Kourothan Village, Sangkat Ou Ambel, Tel: (855) 54 958 821 / 958 634 / 958 541 Krong Serei Saophoan, Banteay Meanchey Province.