NEWSLETTER See Our Web Page at October 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

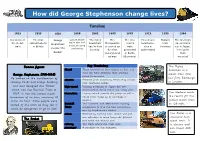

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

The Rainhill Trials Worksheet (Version 2)

The Rainhill Trials Worksheet (Version 2) In 1829 the building of the Liverpool to Manchester railway was nearly complete. The owners of the new railway were unsure which type of train should run on the new train line. They created a competition to help them decide which was the most suitable and fastest train. The winning train would not only be chosen to run on the line, but it would also win £500 prize money. The competition at Rainhill took nine days to complete and over 10,000 people turned up to watch. Rather than travel the whole distance from Liverpool to Manchester, each train was required to travel back and forth along a much shorter 1 mile track. This was to re-create the total 30-mile distance between the two cities. Five trains took part in the Rainhill Trails. They were: The Novelty, The Perseverance, The Sans-Pareil, The Cycloped and The Rocket. Four of the five were machines that were powered by steam. They all had small coal fires on them that would heat water. The steam from the water would be fed into cylinders, the force of the steam would push metal pistons around which in turn would make the wheels turn. The Cycloped was the strangest of all the completion entries and was operated not by steam, but by a horse. The horse ran on a conveyor belt, like a treadmill in a gym. This movement pulled the train wheels along the track. The winner of the completion was of course The Rocket. It covered the 30 miles of track in 3 hours. -

Hackworth Family Archive

Hackworth Family Archive A cataloguing project made possible by the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives Science Museum Group 1 Description of Entire Archive: HACK (fonds level description) Title Hackworth Family Archive Fonds reference code GB 0756 HACK Dates 1810’s-1980’s Extent & Medium of the unit of the 1036 letters with accompanying letters and associated documents, 151 pieces of printed material and printed images, unit of description 13 volumes, 6 drawings, 4 large items Name of creator s Hackworth Family Administrative/Biographical Hackworth, Timothy (b 1786 – d 1850), Railway Engineer was an early railway pioneer who worked for the Stockton History and Darlington Railway Company and had his own engineering works Soho Works, in Shildon, County Durham. He married and had eight children and was a converted Wesleyan Methodist. He manufactured and designed locomotives and other engines and worked with other significant railway individuals of the time, for example George and Robert Stephenson. He was responsible for manufacturing the first locomotive for Russia and British North America. It has been debated historically up to the present day whether Hackworth gained enough recognition for his work. Proponents of Hackworth have suggested that he invented of the ‘blast pipe’ which led to the success of locomotives over other forms of rail transport. His sons other relatives went on to be engineers. His eldest son, John Wesley Hackworth did a lot of work to promote his fathers memory after he died. His daughters, friends, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and ancestors to this day have worked to try and gain him a prominent place in railway history. -

Locomotive: a Powered Railway Vehicle Used for Pulling Trains. The

Lesson 1: What were the Rainhill trials? Vocabulary- Locomotive: a powered railway vehicle used for pulling trains. The meanings of words in bold can be found in the glossary below. In 1829, when the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was approaching completion, the directors ran a competition find the best way of pulling the carriages. Locomotives that were entered were to be subjected to a variety of tests and conditions. Several tests of speed, strength, and efficiency were run over a period of days to see which locomotive would best suit the railway. A prize of £500 (worth over £11,000 today) would also be awarded to the entry chosen. Have a look at the competitors. Who do you think won and who do you think lost? Which do you think was the fastest? Which was the most efficient? (used less fuel) Which ones do you think broke? Disclaimer: The real trains were not made from Lego as this happened over 100 years before Lego was invented. Activity: Read what happened to each of the locomotives (on the next page) and then either write a diary, draw a picture of make a model of what happened that day. Cycloped was the only entry of the five that ran that did not use steam power. It instead relied on a horse-powered drive belt. Built by one of the railway's former directors, people believed it would have an unfair advantage. Cycloped was disqualified for not meeting the contest's rules. Perseverance was the second entry to drop out. It was damaged en route to the site of the trials, and its builder spent five days repairing it. -

Born in 1834 at Killingworth Hall, Northumberland, He Was The

Sir Lindsay Wood Born in 1834 at Killingworth Hall, Northumberland, he was the youngest son of Nicholas Wood, colliery owner and engineer who worked alongside George Stephenson during the early years of locomotive development as well as experimenting with a miners’ safety lamp. He was educated at Kepier Grammar School, Houghton-le-Spring and Kings College ,London. He served an apprenticeship as a mining engineer while working at the Hetton Collieries owned by the Hetton Coal Company. His father was manager of the Hetton Collieries and in 1858 Lindsay was appointed viewer (manager) of the North Hetton Colliery (Moorsley Pit). Shortly afterwards he became assistant to his father as manager of Hetton Collieries and when his father died in 1866 he became Managing Director of the Hetton Collieries which comprised the Lyons Colliery, Moorsley Colliery, the Hazard Pit as well as Eppleton and Elemore Collieries. He continued in this position until the company was sold in 1911 to Lord Joicey’s company. Lindsay Wood was married in 1873 to Emma Barrett of Heighington Hall near Darlington. They initially lived at Hetton Hall but moved to The Hermitage at Chester-le-Street. They had four sons and two daughters the eldest son being Mr. Arthur, Nicholas Lindsay Wood born in 1875. Mr Wood, like his father became a mining engineer and was also a captain in The Northumberland Artillery, a territorial regiment. In 1891 Mrs Emma Wood died suddenly in the late spring at the Hermitage, a great loss to the family. BY the 1870s Lindsay Wood was a managing partner in the North Hetton Coal Company as well as the Harton Coal Company. -

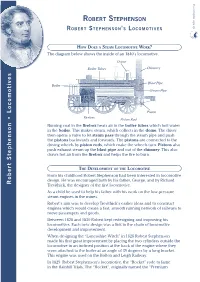

R O B E Rt S Te P H E N S O N • L O C O M O Tiv

ROBERT STEPHENSON ROBERT STEPHENSON’S LOCOMOTIVES HOW DOES A STEAM LOCOMOTIVE WORK? The diagram below shows the inside of an 1840’s locomotive. Dome Boiler Tubes Chimney Blast Pipe Boiler Steam Pipe Piston Firebox Piston Rod Burning coal in the fi rebox heats air in the boiler tubes which boil water in the boiler. This makes steam, which collects in the dome. The driver then opens a valve to let steam pass through the steam pipe and push the pistons backwards and forwards. The pistons are connected to the driving wheels by piston rods, which make the wheels turn. Pistons also push exhaust steam up the blast pipe and out of the chimney. This also draws hot air from the fi rebox and helps the fi re to burn. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LOCOMOTIVE From his childhood Robert Stephenson had been interested in locomotive design. He was encouraged both by his father, George, and by Richard Robert Stephenson • Locomotives Trevithick, the designer of the fi rst locomotive. As a child he used to help his father with his work on the low-pressure steam engines in the mines. Robert’s aim was to develop Trevithick’s earlier ideas and to construct engines which would create a fast, smooth running network of railways to move passengers and goods. Between 1828 and 1830 Robert kept redesigning and improving his locomotives. Each new design was a link in the chain of locomotive development and improvement. When designing the “Lancashire Witch” in 1828 Robert Stephenson made his fi rst great improvement by placing the two cylinders outside the locomotive in an inclined position at the back of the engine where they were attached to the boiler at an angle of 39 degrees by a long bracket. -

Old Newcastle

N O R T H U M B E R L A N D S T St Andrew’s Tyneside Cinema Explore Church A B C D E Find 1 Central Arcade Old Newcastle T EE Theatre Royal TR Amen Corner D3 T S The RKE Bigg Market C2 Gate MA Black Gate D3 Bridge Hotel D4 Grainger Town Castle Keep D3 Castle Stairs D4 Cloth / Flesh Market C2 Blackfriars Cathedral Church of D2 St. Nicholas & Chinatown Rutherford Fountain Church of St. John the Baptist B3 2 BI George Stephenson Monument B3 GG MK Grey Street Literary & Philosophical Society C3 T C North of England C3 LO map and guide heritage Free TH Gateshead Institute of Mining / F LE and Mechanical Engineers S begins story the Where Old G H R O M A Millennium Bridge A Old General Post Office C3 T R K Newcastle M E A T Statue of Queen Victoria D2 R Old Newcastle K E Vermont Hotel D3 T Heritage The Tyne Quayside Y Statue of Queen Victoria R A All Saints’ ChurchTheatre E M N Cathedral Church of St. Nicholas E A S L BALTIC 3 Church of St. John the Baptist ST Explore O OD Centre for Contemporary Art R O NER W S OR G E T C Bessie Surtees House Brandling IN AR MEN Village LL H N A O C I C N C The Sage TO H George Stephenson Monument N Quayside Newcastle E Old General O University Jesmond Vale D Medical L Trinity House School Library Post Office A Welcome to Old Newcastle, Where the Story Begins North of England Institute of Mining S S Discovery & Stephenson Great North Museum and Mechanical EngineersOne square T Black Gate T represents Northern NewcastleE S approximately Visit Old Newcastle to explore nearly There are many more subtle layers and Discovery Museum St. -

Nicholas Wood (1795 – 1865)

Nicholas Wood (1795 – 1865) Nicholas Wood was born at Ryton, a small village on the banks of the River Tyne. He was the son of Nicholas and Ann Wood and he was born on the 24th April 1795. His father was the mining engineer at Crawcrook Colliery close to Ryton, and it was he who would influence his son to follow in his footsteps. Nicholas junior attended the village school in Crawcrook and by 1811 he had started work as an apprentice colliery viewer (manager) at Killingworth colliery some miles to the east of his birthplace. It was here that he became a close associate and friend of the colliery enginewright George Stephenson. Early in their careers both became interested in a revolutionary safety lamp for miners. Wood followed up Stephenson’s work and made drawings of the lamp which eventually was referred to as the “Geordie Lamp” made under supervision by Stephenson. Stephenson who by 1815 had also become interested in the development of the locomotive “Blucher” at Killingworth encouraged Wood to take an active part in the development of the locomotive. Nicholas Wood designed a system of actuating valves and eccentrics for the locomotive and by 1818 he was carrying out experiments on the laminated springs and lubrication of the locomotive’s working parts as well as measuring. There is no question that Wood played a significant role in determining the best type of early locomotive while experimentation was going on. In 1814 he described a single cylinder machine with a flywheel at Wylam colliery as being very troublesome. -

Names in Multi-Lingual

Richard Coates, England 209 A Natural History of Proper Naming in the Context of Emerging Mass Production: The Case of British Railway Locomotives before 1846 Richard Coates England Abstract The early history of railway locomotives in Britain is marked by two striking facts. The first is that many were given proper names, even where there was no objective need to distinguish them in such a way. The second is that those names tended strongly to suggest essential attributes of the machines themselves, sometimes real as in the case of Puffing Billy, or metaphorical or mythologized as in the cases of Rocket and Vulcan. However when, before long, locomotives came to be produced to standard types, namegiving remained the norm for at least some types but the names themselves tended to be typed, and naturally in a less constrained way than earlier ones. The later onymic types veered sharply away from being literally or metaphorically descriptive. The sources of these second-order onymic types are of some interest, both culturally and anthropologically, and some types tended to be of very long currency in Britain. This paper explores the early history of namegiving in an underexplored area, and proposes a general model for the evolution of name-bestowal practices. *** In this paper, I offer an analysis of the names given to steam railway locomotives in Britain between the creation of the first such machine in 1803–4 and the year 1846, chosen semi- arbitrarily as the cut-off date because of the introduction in 1845–6 of the innovative engines designed by Thomas Crampton. -

Unsung Hero of the Railway Celebrated with Upgraded Listings

Unsung hero of the railway celebrated with upgraded listings June 17, 2021 The County Durham residence of pioneering railway engineer Timothy Hackworth (1786 – 1850) has been upgraded to Grade II* by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport on the advice of Historic England, giving it greater protection and recognition. Soho House in Shildon, part of the railway museum at Locomotion, was built for Hackworth by mid-1833 as his main residence. It was originally listed at Grade II in 1986 but has now been elevated into the top 10% of England’s most important historic buildings in recognition of Hackworth’s huge contribution to the success and international influence of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR). As the first Superintendent of Locomotives for the S&DR between 1825 and 1840, Hackworth played a vital role in developing steam engines that met the significant demands of freight and passenger travel. By sharing his experience with visiting engineers and rail promoters he also directly influenced the development of railways on both sides of the Atlantic. When the S&DR was formally opened on 27 September 1825, it marked a crucial step towards the birth of the modern railway network. This was largely thanks to the vision and skill of George Stephenson who designed Locomotion No.1, the first locomotive to run on the S&DR and his business partner Edward Pease, the main promoter of the railway. Together with Michael Longridge of Bedlington and Robert Stephenson they set up Robert Stephenson & Co to build locomotives, which they hoped to sell to emerging railways both in Britain and abroad. -

Great Steam Locomotives

Great Steam Locomotives Since George Stephenson’s Locomotion No. 1 carried its first excited passengers along the Stockton to Darlington railway in 1825, Britain has loved steam locomotives. Railways travelled by steam locomotives let people travel further than they had ever done before and businesses could now transport their goods to market much more quickly. Many great steam locomotives were made and some of them are still famous today. Rocket Flying Scotsman In 1829 father and son team George and Robert The Flying Scotsman was designed by Sir Nigel Stephenson entered their steam locomotive, Rocket, Gresley and built in Doncaster in 1923. The into the Rainhill Trials. This was a competition Flying Scotsman was named because it provided to find a locomotive for the new Liverpool to The Flying Scotsman passenger service between Manchester Railway line. Six locomotives started London and Edinburgh. the competition but the Rocket won. The Flying Scotsman was the first steam To many people the Rocket will always be the locomotive to travel non-stop from London to greatest steam locomotive. It was the fastest of its Edinburgh in 1928 and in 1934 it was the first day reaching a record speed of 29 miles per hour steam locomotive to reach a top speed of 100 in the Rainhill trials. miles per hour. Mallard Evening Star The Mallard was another of Sir Nigel Gresley’s The Evening Star was famous before it was even designs. It was very fast, sleek and could pull long built in 1960 because it was to be the last steam passenger trains at more than 100 miles per hour. -

Stephenson's Newcastle

Literary and Philosophical Society. Philosophical and Literary the Mining Institute and nearby nearby and Institute Mining the Robert left generous bequests to to bequests generous left Robert The Institution of Civil Engineers North East North Engineers Civil of Institution The that institution in 1847. In his will, will, his In 1847. in institution that who was Founder President of of President Founder was who 1849 and 1853 following his father father his following 1853 and 1849 of Mechanical Engineers between between Engineers Mechanical of also president of the Institution Institution the of president also of the Mining Institute and was was and Institute Mining the of Robert was elected vice president president vice elected was Robert was 15 years old. years 15 was commencing employment when he he when employment commencing INSTITUTION OFCIVILENGINEERS apprenticed to Nicholas Wood on on Wood Nicholas to apprenticed Robert Stephenson was was Stephenson Robert and friend of George Stephenson. Stephenson. George of friend and (manager), associate, colleague colleague associate, (manager), was a prominent Colliery Viewer Viewer Colliery prominent a was Wood Memorial Library. Nicholas Nicholas Library. Memorial Wood The building houses the Nicholas Nicholas the houses building The North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers Mechanical and Mining of Institute England of North The 5 Stephenson’s Newcastle Stephenson’s ICE 200 ICE projections housing figures depicting Stephenson’s spheres of activity. of spheres Stephenson’s depicting figures housing projections The monument depicts George Stephenson on the pedestal with corner corner with pedestal the on Stephenson George depicts monument The widened in 1894.