Names in Multi-Lingual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

60163 TORNADO New Steam for the Main Line

60163 TORNADO New Steam for the Main Line Thursday 28th April 2011 Dear fellow covenantor Changes to Tornado’s 2011 tours diary and Brunswick Green unveiling at the National Railway Museum There have been a number of developments since the enclosed edition of The Communication Cord went to press that the Trustees of The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust need to share with you. We regret that it has not been possible to reach an acceptable working arrangement with Train Operating Company West Coast Railways in spite of many attempts over the past three years. Tornado will continue to be operated on the Network Rail main line by DB Schenker, which has worked successfully with the Trust since the locomotive’s completion in 2008. This change is unrelated to the recently completed repairs to Tornado’s boiler which took place at DB Meiningen. Unfortunately, this late change will result in a significant re-working of Tornado’s tours diary for the early part of the summer. As a consequence of not being able to work with West Coast Railways, Tornado will not now be hauling ‘The Cathedrals Express’ on Thursday 26th May (London to Bath & Bristol and return), Saturday 4th June (London King's Cross to York and return) and Saturday 11th June (London to Shrewsbury and return) promoted by Steam Dreams. The promoter will be in contact separately with those of you who originally booked on ‘The White Rose’ and transferred to ‘The Cathedrals Express on 4th June. Although Tornado will be ready for traffic for 26th May, her first main line train in her new Brunswick Green livery will now be ‘The Canterbury Tornado’ on Saturday 18th June from Poole (Tornado from Willesden) to Canterbury and return promoted by Pathfinder. -

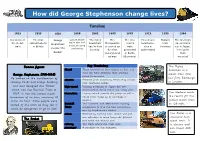

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

Serial Asset Type Active Designation Or Undertaking?

Serial Asset Type Active Description of Record or Artefact Registered Disposal to / Date of Designation, Designation or Number Current Designation Class Designation Undertaking? Responsible Meeting or Undertaking Organisation 1 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1995/01 Network Rail 22/09/1995 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Infrastructure Ltd associated Companies between 1833 and 1859 [operational property] 2 Disposed NO The Gooch Centrepiece 1995/02 National Railway 22/09/1995 Disposal Museum 3 Replaced NO Classes of Record: Memorandum and Articles 1995/03 N/A 24/11/1995 Designation of Association; Annual Reports; Minutes and working papers of main board; principal subsidiaries and any sub-committees whether standing or ad hoc; Organisation charts; Staff newsletters/papers and magazines; Files relating to preparation of principal legislation where company was in lead in introducing legislation 4 Disposed NO Railtrack Group PLC Archive 1995/03 National Railway 24/11/1995 Disposal Museum 5 YES Class 08 Locomotive no. 08616 (formerly D 1996/01 London & 22/03/1996 Designation 3783) (last locomotive to be rebuilt at Birmingham Swindon Works) Railway Ltd 6 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1996/02 BRB (Residuary) 22/03/1996 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Ltd associated Companies between 1833 and 1859 [Non-operational property] 7 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1996/02 Network Rail 22/03/1996 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Infrastructure -

BR Standard Class 6 'Clan Class' Drivers Guide

BR Standard Class 6 'Clan Class' Drivers Guide Steam locomotive expansion pack for Train Simulator BR Standard Class 6 'Clan Class' 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 Locomotives ...................................................................................................................... 4 Tenders ............................................................................................................................. 8 Coaches .......................................................................................................................... 11 The ‘Clan’ Project ............................................................................................................ 13 History ......................................................................................................................... 13 72010 modifications ..................................................................................................... 14 The ‘Clan’ Project Patron and President ...................................................................... 15 Where will the locomotive run and where will it be based? ........................................... 16 What will it cost? .......................................................................................................... 16 Find out more ............................................................................................................... 17 INSTALLATION ................................................................................................................. -

Lot 1066 (100% GST)BAY OR BROWN COLT Stable B 1 Foaled 22Nd September 2018 Branded : Nr Sh; 11 Over 8 Off Sh

Account of BYERLEY STUD, Sandy Hollow, NSW. Lot 1066 (100% GST)BAY OR BROWN COLT Stable B 1 Foaled 22nd September 2018 Branded : nr sh; 11 over 8 off sh Sire Bianconi Danzig ............................. Northern Dancer NICCONI Fall Aspen .................................... Pretense 2005 Nicola Lass Scenic .................................. Sadler's Wells Dubai Lass ................................ Bletchingly Dam Statue of Liberty Storm Cat .................................. Storm Bird LADY OF LIBERTY Charming Lassie ................... Seattle Slew 2013 Export Lady Export Price .................................... Habitat Lady Violet ................................. Old Crony NICCONI (AUS) (Bay 2005-Stud 2010). 6 wins-1 at 2, VRC Lightning S., Gr.1. Sire of 423 rnrs, 311 wnrs, 18 SW, inc. SW Nature Strip (ATC Galaxy H., Gr.1), Faatinah, Sircconi, Chill Party, Nicoscene, Niccanova, Time Awaits, Concealer, Tony Nicconi, Hear the Chant, State Solicitor, Caipirinha, Nistaan, It's Been a Battle, Ayers Rock, Quatronic, Exclusive Lass, Loved Up, SP Lankan Star, Niccovi, Akkadian, Mandylion, Shokora, etc. 1st dam LADY OF LIBERTY, by Statue of Liberty. Raced twice. Three-quarter-sister to TEMPEST TOST (dam of MILDRED). This is her first foal. 2nd dam EXPORT LADY, by Export Price. 2 wins at 1200m. Sister to NOTOIRE, Violet Haze (dam of SINO BRILHANTE), half-sister to TEMPEST TOST (dam of MILDRED), WELL KNOWN, Livigno, Tullamarine, Springburn (dam of (MY) NIKITA, HAPPY HIPPY). Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 5 winners, inc:- Black Bubble. 6 wins 1000m to 1200m, $150,450, VRC Aluminates Chemical Industries H., MRC Gecko Solutions Training H., San Domenico H. Sneem. 6 wins-4 in succession-to 1300m, QTC Paul Carter Solicitor H. 3rd dam LADY VIOLET, by Old Crony. -

The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive, 1803 to 1898 (1899)

> g s J> ° "^ Q as : F7 lA-dh-**^) THE EVOLUTION OF THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE (1803 to 1898.) BY Q. A. SEKON, Editor of the "Railway Magazine" and "Hallway Year Book, Author of "A History of the Great Western Railway," *•., 4*. SECOND EDITION (Enlarged). £on&on THE RAILWAY PUBLISHING CO., Ltd., 79 and 80, Temple Chambers, Temple Avenue, E.C. 1899. T3 in PKEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. When, ten days ago, the first copy of the " Evolution of the Steam Locomotive" was ready for sale, I did not expect to be called upon to write a preface for a new edition before 240 hours had expired. The author cannot but be gratified to know that the whole of the extremely large first edition was exhausted practically upon publication, and since many would-be readers are still unsupplied, the demand for another edition is pressing. Under these circumstances but slight modifications have been made in the original text, although additional particulars and illustrations have been inserted in the new edition. The new matter relates to the locomotives of the North Staffordshire, London., Tilbury, and Southend, Great Western, and London and North Western Railways. I sincerely thank the many correspondents who, in the few days that have elapsed since the publication: of the "Evolution of the , Steam Locomotive," have so readily assured me of - their hearty appreciation of the book. rj .;! G. A. SEKON. -! January, 1899. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. In connection with the marvellous growth of our railway system there is nothing of so paramount importance and interest as the evolution of the locomotive steam engine. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

The Communication Cord Is Rather “P2 from Acorns Grow”

60163 TORNADO 2007 PRINCE OF WALES 3403 ANON New Steam for the Main Line Building Britain’s Most Powerful Steam Locomotive Recreating Gresley’s last design THE COMMUNICATION CORD No. 61 Spring 2021 Simon Apsley/Frewer & Co. Engineers A superb rendering by Simon Apsley of the 3D CAD of Prince of Wales's front end, cut away to show the Lentz gearbox and the double Kylchap exhaust in the smokebox. POETRY IN MOTION? by Graham Langer Despite the difficulties of the past year has involved Frewer and Co. Engineers of No. 2007 – in consequence he has the P2 project continues to forge ahead undertaking the Computational Fluid been sending us the most impressive and we have reached the stage of fine- Dynamics [CFD] analysis of the cylinder renderings of parts and sections of tuning the design for the cylinders and block steam passageways and one of the new P2, some of which we are valve gear so that construction can be their team, Simon Apsley, has got a delighted to feature in this edition of The put out to tender. Part of the process bit carried away with the 3D CADs Communication Cord. TCC 1 CONTENTS EDITORIAL by Graham Langer FROM THE CHAIR by Steve Davies PAGE 1 Poetry in motion? As I write this towards the use of coal. However, the n recent weeks time, from Leicester to Carlisle via the physically meeting. Video conferencing is PAGE 2 editorial Tornado sector produces a tiny percentage of we have all felt spectacular Settle & Carlisle Railway. It probably here to stay but punctuated by Contents is still “confined to the country’s greenhouse gasses and Idrawn even might seem premature to say this, but I periodic ‘actual’ meetings. -

The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway

The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit Volume 1: Significance & Management October 2016 Archaeo-Environment for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton on Tees Borough Council. Archaeo-Environment Ltd for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Borough Council 1 The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. Executive Summary The ‘greatest idea of modern times’ (Jeans 1974, 74). This report arises from a project jointly commissioned by the three local authorities of Darlington Borough Council, Durham County Council and Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council which have within their boundaries the remains of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) which was formally opened on the 27th September 1825. The report identifies why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and sets out its significance and unique selling point. This builds upon the work already undertaken as part of the Friends of Stockton and Darlington Railway Conference in June 2015 and in particular the paper given by Andy Guy on the significance of the 1825 S&DR line (Guy 2015). This report provides an action plan and makes recommendations for the conservation, interpretation and management of this world class heritage so that it can take centre stage in a programme of heritage led economic and social regeneration by 2025 and the bicentenary of the opening of the line. More specifically, the brief for this Heritage Trackbed Audit comprised a number of distinct outputs and the results are summarised as follows: A. Identify why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and clearly articulate its significance and unique selling point. -

“How Strangely Chang'd”: the Re-Creation of Ovid by African

“How Strangely Chang’d”: The Re-creation of Ovid by African American Women Poets By Rachel C. Morrison Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ______________________________________ Chair: Emma Scioli ______________________________________ Pam Gordon ______________________________________ Tara Welch Date Approved: 10 May 2018 The thesis committee for Rachel C. Morrison certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: “How Strangely Chang’d”: The Re-creation of Ovid by African American Women Poets ______________________________________ Chair: Emma Scioli ______________________________________ Pam Gordon ______________________________________ Tara Welch Date Approved: 10 May 2018 ii Abstract This project examines the re-creation of Ovid by African American women poets. Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved Black woman writing in colonial America, engages with Ovid’s account of Niobe in her epyllion “Niobe in Distress.” Henrietta Cordelia Ray, who was active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, picks up where Wheatley left off in a sonnet called “Niobe.” Elsewhere, in “Echo’s Complaint,” Ray also imagines what Echo might say to Narcissus if she had full control over her words—an imaginative exercise that has resonances with Ovid’s Heroides. Finally, in her 1995 book Mother Love, the contemporary poet Rita Dove re-examines the tale of Demeter and Persephone from a number of different angles. In reworking the Metamorphoses, all three poets paint vivid images of vulnerable girls and bereft mothers. Moreover, Wheatley, Ray, and Dove play with Ovidian elements to explore themes of repetition, voice, motherhood, and power dynamics. -

The Royal Navy, October 1801

The Royal Navy October 1801 At Home San Josef 112 Ville de Paris 110 Royal George 100 Royal Sovereign 100 Atlas 98 Barfleur 98 Formidable 98 Glory 98 London 98 Neptune 98 Prince 98 Prince George 98 Princess Royal 98 Prince of Wales 98 Temeraire 98 Windsor Castle 98 Namur 90 Malta 80 Donegal 80 Juste 80 Hercule 74 Achilles 74 Belleisle 74 Bellerophon 74 Blenheim 74 Brunswick 74 Canada 74 Captain 74 Centaur 74 Courageux 74 Defiance 74 Edgar 74 Elephant 74 Excellent 74 Impetueux 74 Irresistible 74 Magnificent 74 Majestic 74 Mars 74 Monarch 74 Orion 74 Princess of Orange 74 Resolution 74 Robust 74 Saturn 74 Terrible 74 Theseus 74 Thunderer 74 Vengeance 74 1 Leyden 68 De Ruyter 68 Agamemnon 64 Ardent 64 Asia 64 Polyphemus 64 Raisonnable 64 Ruby 64 St. Albans 64 Standard 64 Veteran 64 York 64 Batavia 54 Beschermer 54 Isis 50 Loire 46 Amelia 44 Anson 44 Fisgard 44 FortunQe 44 Indefatigable 44 Revolutionnaire 44 Serapis 44 Vlieter 44 Acasta 40 Beaulieu 40 Cambrian 40 Desire 40 Princess Charlotte 40 San Firoenzo 40 Amazon 38 Amethyst 38 Boadecia 38 Clyde 38 Diamond 38 Diana 38 Hussar 38 Latona 38 Medusa 38 Naiade 38 Unité 38 Urania 38 Alceste 36 Ambuscade 36 Blanche 36 Dedaigneuse 36 Doris 36 Dryad 36 Glenmore 36 Immortalité 36 Nymphe 36 Oiseau 36 Phoebe 36 Sirius 36 Thalia 36 2 Trent 36 Surprize 34 Aquilon 32 Aeolus 32 Castor 32 Galathea 32 Lowestoffe 32 Magicienne 32 Maidstone 32 Narcissus 32 Shannon 32 Tartar 32 Triton 32 Unicorn 32 Arrow 30 Dart 30 Amphitrite 28 Brilliant 28 Enterprize 28 Heldin 28 Lapwig 28 Nemesis 28 Jamaica 26 Waakzamheid -

Steam-Engine

CHAPTER IV. .J.1JE MODERN STEAM-ENGINE. "THOSE projects which abridge distance bnve done most for the civiliza ..tion and happiness of our species."-MACAULAY. THE SECOND PERIOD OF APPLIC.ATION-18OO-'4O. STE.AM-LOCOMOTION ON RAILROADS. lNTRODUCTORY.-The commencement of the nineteenth century found the modern steam-engine fully developed in .. :.... �::�£:��r:- ::::. Fro. 40.-The First Railroad-Car, 1S25. a.11 its principal features, and fairly at work in many depart ments of industry. The genius of Worcester, and Morland, and Savery, and Dcsaguliers, had, in the first period of the · STEA�l-LOCOMOTION ON RAILROADS. 145 application of the po,ver of steam to useful ,vork, effected a beginning ,vhich, looked upon from a point of vie,v vvhich · exhibits its importance as the first step to,vard the wonder ful results to-day familiar to every one, appears in its true light, and entitles those great men to even greater honor than has been accorded them. The results actually accom plishecl, ho,vever, were absolutely. insignificant in compari son with those ,vhich marked the period of development just described. Yet even the work of Watt and of his con temporaries ,vas but a 1nere prelude to the marvellous ad vances made in the succeeding period, to which ,ve are now come, and, in · extent and importance, was insignificant in co1nparison ,vith that accomplishecl by tl1eir successors in · the development of all mechanical industries by the appli cation of the steam-engine to the movement of every kind of machine. 'fhe firstof the two periods of application saw the steam engine adapted simply to tl1e elevation of water and t,he drainage of mines ; during the second period it ,vas adapted to every variety of use£ul ,vork, and introduced ,vherever the muscular strength of men and animals, or the power of ,vind and of falling ,vater, ,vl1ich had previously been the only motors, had found application.