2008-Sgipos-8.Pdf

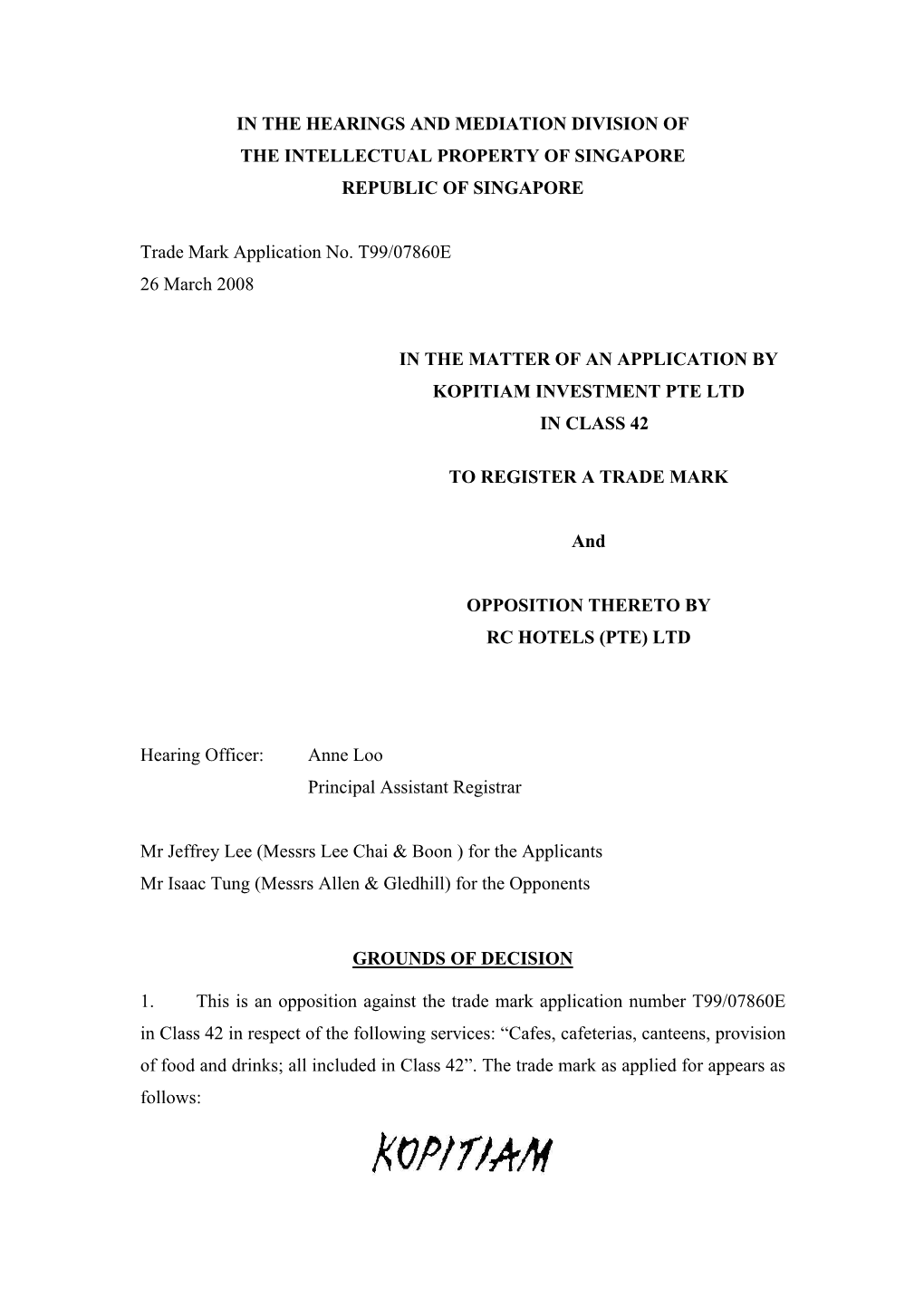

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A MODERN-SINGAPOREAN CHRISTMAS Top Stories

Presenting A MODERN-SINGAPOREAN CHRISTMAS Top Stories Shine & sizzle with a Mod-Sin spin this Christmas to spice up your festive table! 16% Early Bird Discount for festive takeaway items. All-you-can-eat Buffet (served à la carte). Sleigh into to our heritage building for a yummy fulfilment to kick- start your festive celebrations this Christmas. Exclusive News Christmas Eve Dinner Dazzle yourself with a 24th Dec 2020 Modern-Singaporean 2 seatings: (Mod-Sin) Christmas... jolly 1800 - 1930 hrs tables filled with ingredients 1930 - 2100 hrs of a truly Merry Christmas Adult: $58++ seasoned with love & a dash Child: $29++ of enchantment. Christmas Day Tantalise your taste buds Brunch with our unique festive 25th Dec 2020 dishes; from our savoury 2 seatings: Laksa Turkey Pie to our sweet Ang Ku Kueh Log 1100 - 1230 hrs Cake, be marvelled by 1230 - 1400 hrs Assam Nenas ‘Carbonara’ Gratin Lobster choices aplenty. Adult: $48++ ++ All prices for dine-in are quoted in Singapore dollars and are subject to 10% service charge & prevailing government taxes (e.g. GST). Child: $24 CONNECT WITH US FLIP FOR MORE @BABACHEWSSG @BABACHEWS Festive Takeaways Let your spirits run high with our Mod- Sin rendition of the Christmas turkey. Our Turkey Ngoh Hiang ‘Golden Pillow’ is turkey breast rolled into a roulade with fillings of minced meat and vegetables & enveloped in a beancurd skin. Another local favourite with a modern spin is our Laksa Turkey Pie - a combination of the holiday pie with Singapore’s staple of our local favourite dish. Turkey Ngoh Hiang ‘Golden Pillow’ ‘Kopi C’ Flavoured BBQ Pork Spareribs Baba’s Beef Rendang Laksa Turkey Pie Your usual festive spread with a Mod-Sin twist that will make you go “Baba-Mia”! Seafood lovers will enjoy our Assam Nenas ‘Carbonara’ Gratin Lobster - Bamboo lobster in assam curry sauce“ gratinated with cream and cheese. -

SNACKS) Tahu Gimbal Fried Tofu, Freshly-Grounded Peanut Sauce

GUBUG STALLS MENU KUDAPAN (SNACKS) Tahu Gimbal Fried Tofu, Freshly-Grounded Peanut Sauce Tahu Tek Tek (v) Fried Tofu, Steamed Potatoes, Beansprouts, Rice Cakes, Eggs, Prawn Paste-Peanut Sauce Pempek Goreng Telur Traditional Fish Cakes, Egg Noodles, Vinegar Sauce Aneka Gorengan Kampung (v) Fried Tempeh, Fried Tofu, Fried Springrolls, Traditional Sambal, Sweet Soy Sauce Aneka Sate Nusantara Chicken Satay, Beef Satay, Satay ‘Lilit’, Peanut Sauce, Sweet Soy Sauce, Sambal ‘Matah’ KUAH (SOUP) Empal Gentong Braised Beef, Coconut-Milk Beef Broth, Chives, Dried Chili, Rice Crackers, Rice Cakes Roti Jala Lace Pancakes, Chicken Curry, Curry Leaves, Cinnamon, Pickled Pineapples Mie Bakso Sumsum Indonesian Beef Meatballs, Roasted Bone Marrow, Egg Noodles Tengkleng Iga Sapi Braised Beef Ribs, Spicy Beef Broth, Rice Cakes Soto Mie Risol Vegetables-filled Pancakes, Braised Beef, Beef Knuckles, Egg Noodle, Clear Beef Broth 01 GUBUG STALLS MENU SAJIAN (MAIN COURSE) Pasar Ikan Kedonganan Assorted Grilled Seafood from Kedonganan Fish Market, ‘Lawar Putih’, Sambal ‘Matah’, Sambal ‘Merah’, Sambal ‘Kecap’, Steamed Rice Kambing Guling Indonesian Spices Marinated Roast Lamb, Rice Cake, Pickled Cucumbers Sapi Panggang Kecap – Ketan Bakar Indonesian Spices Marinated Roast Beef, Sticky Rice, Pickled Cucumbers Nasi Campur Bali Fragrant Rice, Shredded Chicken, Coconut Shred- ded Beef, Satay ‘Lilit’, Long Beans, Boiled Egg, Dried Potato Chips, Sambal ‘Matah’, Crackers Nasi Liwet Solo Coconut Milk-infused Rice, Coconut Milk Turmeric Chicken, Pumpkin, Marinated Tofu & -

Entree Beverages

Beverages Entree HOT/ COLD MOCKTAIL • Sambal Ikan Bilis Kacang $ 6 Spicy anchovies with peanuts $ 4.5 • Longing for Longan $ 7 • Teh Tarik longan, lychee jelly and lemon zest $ 4.5 • Kopi Tarik $ 7 • Spring Rolls $ 6.5 • Milo $ 4.5 • Rambutan Rocks rambutan, coconut jelly and rose syrup Vegetables wrapped in popia skin. (4 pieces) • Teh O $ 3.5 • Mango Madness $ 7 • Kopi O $ 3.5 mango, green apple and coconut jelly $ 6.5 • Tropical Crush $ 7 • Samosa pineapple, orange and lime zest Curry potato wrapped in popia skin. (5 pieces) COLD • Coconut Craze $ 7 coconut juice and pulp, with milk and vanilla ice cream • Satay $ 10 • 3 Layered Tea $ 6 black tea layered with palm sugar and Chicken or Beef skewers served with nasi impit (compressed rice), cucumber, evaporated milk onions and homemade peanut sauce. (4 sticks) • Root Beer Float $ 6 FRESH JUICE sarsaparilla with ice cream $ 10 $ 6 • Tauhu Sumbat • Soya Bean Cincau $5.5 • Apple Juice A popular street snack. Fresh crispy vegetables stuff in golden deep fried tofu. soya bean milk served with grass jelly • Orange Juice $ 6 • Teh O Ais Limau $ 5 • Carrot Juice $ 6 ice lemon tea $ 6 • Watermelon Juice $ 12 $ 5 • Kerabu Apple • freshAir Kelapa coconut juice Muda with pulp Crisp green apple salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with deep $ 5 fried chicken. • Sirap Bandung Muar rose syrup with milk and cream soda COFFEE $ 5 • Dinosaur Milo $ 12 malaysian favourite choco-malt drink • Beef Noodle Salad $ 4.5 Noodle salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with marinated beef. -

Kopi Luwak Coffee

KOPI LUWAK KOPI LUWAK “THE WORLD’S MOST EXPENSIVE COFFEE” “THE WORLD’S MOST EXPENSIVE COFFEE” An Asian palm civet eating the red berries of an Indonesian coffee plant. An Asian palm civet eating the red berries of an Indonesian coffee plant. Most expensive coffee in the world? Maybe. Kopi Luwak, or Civet Coffee, is really expensive. Most expensive coffee in the world? Maybe. Kopi Luwak, or Civet Coffee, is really expensive. We’re talking $60 for 4 ounces, or in some Indonesian coffee shops, $10 per cup. It is We’re talking $60 for 4 ounces, or in some Indonesian coffee shops, $10 per cup. It is undoubtedly a very rare cup of coffee. undoubtedly a very rare cup of coffee. Tasting notes: vegetabley, tea-like and earthy Tasting notes: vegetabley, tea-like and earthy *We sourced these beans from a small coffee farmer in Bali, Indonesia *We sourced these beans from a small coffee farmer in Bali, Indonesia and the roasting is done here in the states. and the roasting is done here in the states. So, what is Kopi Luwak? So, what is Kopi Luwak? Coffee beans are actually seeds found in the pit of cherry-sized fruits on the coffee plant. Coffee beans are actually seeds found in the pit of cherry-sized fruits on the coffee plant. Before coffee beans are ready to be sold to the consumer, they are separated from the flesh of Before coffee beans are ready to be sold to the consumer, they are separated from the flesh of the fruit, fermented, and roasted. -

Halal Kopitiam Choices Among Young Muslim Consumers in Northern Region of Peninsular Malaysia

Volume: 4 Issues: 21 [June, 2019] pp. 13 -21] Journal of Islamic, Social, Economics and Development (JISED) eISSN: 0128-1755 Journal website: www.jised.com HALAL KOPITIAM CHOICES AMONG YOUNG MUSLIM CONSUMERS IN NORTHERN REGION OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA Ismalaili Ismail1 Nik Azlina Nik Abdullah2 Syazwani Ya3 Rozihana Sheikh Zain4 Noor Asyikin Mohd Noor5 1Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Perlis Branch, Malaysia, (E-mail: [email protected]) 2Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Perlis Branch, Malaysia, (E-mail: [email protected]) 3Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Perlis Branch, Malaysia, (E-mail: [email protected]) 4Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Perlis Branch, Malaysia, (E-mail: [email protected]) 5Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Perlis Branch, Malaysia, (E-mail: [email protected]) Accepted date: 13-04-2019 Published date: 01-07-2019 To cite this document: Ismail, I., Nik Abdullah, N. A., Ya, S., Sheikh Zain, R., & Mohd Noor, N. A. (2019). Halal Kopitiam Choices among Young Muslim Consumers in Northern Region of Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Islamic, Social, Economics and Development (JISED), 4(21), 13-21. ___________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Recently, there is an increasing statistic towards Halal industry which 60 percent of the annual global market value is generated from Halal food business including Halal kopitiam and restaurants. Halal defined as permissible and lawful according to Quran and Sharia. In Malaysian context, food producers such as Halal kopitiam are compulsory to follow the standards set by JAKIM and Islamic law in handling their food preparation. -

Product Catalog

Gin Seng Industrial (M) Sdn. Bhd. IPOH TONGKAT ALI WHITE COFFEE Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Ipoh tongkat ali white coffee 4 in 1 10 sachets x 20g MUSANG KING DURIAN BISCUIT Category Biscuits Brand KingStar Description Cholesterol FREE Trans fat FREE Low in sodium Source of dietary fibre 6pcs X 40g 1 of 5 DURIAN WHITE COFFEE Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Durian white coffee 4 in 1 10 sachets x 30g IPOH WHITE COFFEE CAPPUCCINO 3 in 1 Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Ipoh white coffee cappuccino 3 in 1 10 sachets x 40g RAHMAN IPOH WHITE MILK TEA Category White Tea Brand KingStar Description Rahman ipoh white milk tea 3 in 1 12 sachets x 25gm 2 of 5 KOPI LUWAK Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Kopi luwak 3 in 1 9 sachets 25g IPOH WHITE COFFEE CAPPUCCINO 2 in 1 Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Ipoh white coffee cappuccino 2 in 1 No added sugar 15 sachets x 25gm HAZELNUT IPOH WHITE COFFEE Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Hazelnut ipoh white coffee 4 in 1 10 sachets x 30g Mangosteen White Coffee Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Mangosteen Ipoh White Coffee 4 in 1 10 sachets x 30g (1.05oz) Paquetes 3 of 5 StarGold Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description StarGold Ipoh White Coffee 3 in 1 15 sachets X 30g Cordyceps White Coffee Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Cordyceps White Coffee 4 in 1 10 sachets x 30g 4 of 5 Blue Mountain Coffee Category Instant Coffee Brand KingStar Description Blue Mountain Coffee 3 in 1 10 sachets x 30g Gin Seng Industrial (M) Sdn. -

Take Away Menu MF31 Milo (Cold) $ 3.90 MF32 Milo (Hot) $ 3.50

Malaysian Favourites MF01 Lychee Grass Jelly $ 5.90 MF02 Fresh Lemon Honey (Hot) $ 3.50 MF03 Lemon Tea with Honey $ 3.50 MF04 Red Bean $ 4.90 MF05 Fresh Lemon Honey (Cold) $ 3.90 MF06 Lemon Tea $ 3.90 MF07 Barley (Cold) $ 3.90 MF08 Barley Grass Jelly $ 4.20 MF09 Organic Soya Milk (Cold) $ 3.90 MF10 Soya Milk Grass Jelly $ 4.20 MF11 Soya Milk + Sesame Ice Cream $ 5.80 MF12 Soya Milk Jelly $ 4.90 MF13 Soya Milk Pudding $ 4.90 MF14 Soya Milk Pudding + Grass Jelly $ 4.90 MF15 Teh (Hot) $ 3.50 MF16 Kopi (Hot) $ 3.50 MF17 Kopi O (Hot) $ 3.50 MF18 Kopi Cham Milo (Hot) $ 3.80 MF19 Teh (Cold) $ 3.90 MF20 Kopi (Cold) $ 3.90 MF21 Kopi O (Cold) $ 3.90 MF22 Kopi Cham Milo (Cold) $ 4.20 MF23 Milo Dinosaur $ 4.90 MF24 Chocolate (Cold) $ 4.20 MF25 Teh + Jelly $ 4.90 MF26 Teh C Special $ 3.90 MF27 Barley (Hot) $ 3.50 MF28 Organic Soya Milk (Hot) $ 3.50 MF29 Jasmine Tea $ 1.50 MF30 Chocolate (Hot) $ 3.50 Take Away Menu MF31 Milo (Cold) $ 3.90 MF32 Milo (Hot) $ 3.50 Pappa Delicious Concoctions PD01 Ribena Melon $ 5.90 PD02 Mango Mania $ 5.90 Melbourne CBD PD03 Matcha Rocks $ 7.20 Shop 11, Qv Square, PD04 Open Sesame $ 7.20 Qv Building, Melbourne, Italian Coffee Selection VIC 3000 IC01 Cappuccino (Regular) $ 3.30 03 9654 2682 IC02 Cappucino (Large) $ 3.80 IC03 Latte (Regular) $ 3.30 IC04 Latte (Large) $ 3.80 Chadstone IC05 Flat White (Regular) $ 3.30 Shop F029, Chadstone IC06 Flat White (Large) $ 3.80 Shopping Centre, IC07 Expresso (Regular) $ 3.30 VIC 3148 IC08 Long Black (Regular) $ 3.30 IC09 Long Black (Large) $ 3.80 03 9568 3323 IC10 Macchiato (Short) -

Kopi Teman Sejati Introduction

KOPI TEMAN SEJATI INTRODUCTION • “Kopi Teman Sejati” is Created by 2 brothers whose have passion in F&B Industry • We have the passion to serve Indonesian with fine and authentic coffee taste from Indonesian local grown coffee beans. • We will bring the modern mix coffee and also bring back the old style coffee mixing drinks. • We will also serve our future customers with Tea and milk based drinks as for complementary. • In modern lifestyle there’s demand for coffee drinks to support their hectic lifestyle, that’s why Indonesia coffee market keep growing with Coffee drinker and also other Mixed drinks. Our Main Customers mostly are • Genders : Male & Female • Age : 18 – 34 Years Old • Social Class : Middle & Middle TARGET Up Class • Occupation : College Students, MARKET Working young Adult, Young Housewife Psychographic : • Young Peoples with hectic lifestyle which in needs for Energy and Mood booster to seize the day. BRAND IDENTITY • Brand Personality • Authentic • Energetic • Joyful • Confident • Tagline : • “Selalu ada menemani” DESIGN BRIEF LOGO DESIGN BRIEF • We need a new logo design for new brand “Kopi Teman Sejati” • The logo need to be shown : • Friends Bonding relationship • Authentic • Boosting Energy dan Mood • Happy Feeling • There are so many coffee brand in the market but we want to make it distinct from all those brands • Our Brand logo need to easy recognize COLOR COMBINATION • Main Combination Colors abaikan logo perhatikan warna saja : Orange & Dark Charcoal Grey Color • Orange combines the energy of Red and the Combination happiness of Yellow. • Orange also represents enthusiasm, fascination, happiness, creativity, determination, attraction, success, encouragement, and stimulation • orange is associated with healthy food and stimulates appetite LOGO DESIGN BRIEF • The Logo has to represent the authenticity of our products which our product will be serve from small kiosk which is more space efficient so it help to reduce the cost. -

(Kopi Luwak) and Ethiopian Civet Coffee

Food Research International 37 (2004) 901–912 www.elsevier.com/locate/foodres Composition and properties of Indonesian palm civet coffee (Kopi Luwak) and Ethiopian civet coffee Massimo F. Marcone * Department of Food Science, Ontario Agricultural College, Guelph, Ont., Canada N1G 2W1 Received 19 May 2004; accepted 25 May 2004 Abstract This research paper reports on the findings of the first scientific investigation into the various physicochemical properties of the palm civet (Kopi Luwak coffee bean) from Indonesia and their comparison to the first African civet coffee beans collected in Ethiopia in eastern Africa. Examination of the palm civet (Kopi Luwak) and African civet coffee beans indicate that major physical differences exist between them especially with regards to their overall color. All civet coffee beans appear to possess a higher level of red color hue and being overall darker in color than their control counterparts. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that all civet coffee beans possessed surface micro-pitting (as viewed at 10,000Â magnification) caused by the action of gastric juices and digestive enzymes during digestion. Large deformation mechanical rheology testing revealed that civet coffee beans were in fact harder and more brittle in nature than their control counterparts indicating that gestive juices were entering into the beans and modifying the micro-structural properties of these beans. SDS–PAGE also supported this observation by revealing that proteolytic enzymes were penetrating into all the civet beans and causing substantial breakdown of storage proteins. Differences were noted in the types of subunits which were most susceptible to proteolysis between civet types and therefore lead to differences in maillard browning products and therefore flavor and aroma profiles. -

Menukaart-ENG-A3.Indd

SIDE DISHES per portion DRINKS Nasi Putih (white rice) 3 Soft drinks Lontong (compressed rice in cubes) 3.5 Non Sparkling water / Sparkling water 2.95 Nasi Kuning (yellow rice with coconut) 3.5 Coca Cola Original / Light / Zero 2.95 Bami Goreng (fried noodles with egg) mild or spicy 3.5 Fanta 2.95 Nasi Goreng (fried rice with egg) mild or spicy 3.5 Fernandes Green / Red 2.95 Nasi Goreng Ikan Roa 4.5 Ice Tea Sparkling / Green 2.95 Bami Goreng Ikan Roa 4.5 Sprite 2.95 Tonic 2.95 Kerupuk (deep fried prawn crackers) 2 Bitter Lemon 2.95 Emping (deep fried melinjo nuts crackers) 3 Teh Botol (Indonesian ice tea) 2.95 Susuroos Siroop 3.25 Serundeng (homemade fried coconut fakes) 2 Mazaa Lychee / Mango Juice 3.75 Peanut sauce (homemade) 2.5 Warm drinks Tea (various tastes) 2.95 Teh Jawa (Javanese tea) 3.75 SNACKS Coffee 2.75 Coffee Decaf 2.95 Lumpia (chicken / vega) 3.10 Cappuccino 3.95 Spring roll flled with (chicken), bamboo shoots and tofu Coffee Latte 4.75 Espresso 3.25 Pisang Goreng 3.10 Double Espresso 4.25 Deep fried banan Kopi Tubruk (Indonesian black coffee) 4.5 Rissoles (chicken / vega) 3.10 Indonesian croquette flled with chicken ragout / INDONESIAN VIRGIN COCKTAIL vegetable ragout and carrot MENU Es Lemon Grass 4.5 Pastei (chicken / vega) 3.10 Homemade iced tea from fresh lemon, ginger and Fried pasty flled with (chicken), rice vermicelli lemongrass ENGLISH and vegetables Hot Lemon Grass 4.5 Indonesische kroket 3.10 Homemade hot tea from fresh lemon, ginger and Indonesian potato croquette flled with minced beef lemongrass and vegetables -

Rames Schotel Rijsttafel

A LA CARTE RAMES SCHOTEL CHICKEN DISHES PER PORTION Sayur Lodeh 3 A mix of cabbage, beans, carrots and corn in Gado-Gado 8 Rames BANDUNG from 11* Ayam Suwir 5 coconut sauce A mix of steamed bean sprouts, cabbage and green Nasi Putih* | Ayam Cashew | Daging Semur Jakarta | Mild spicy grated chicken in coconut sauce beans, fried tofu and tempe with hard-boiled egg. Sambal Goreng Buncis | Sambal Goreng Telor | Kerupuk Sambal Goreng Terong 5 Served with homemade peanut sauce dressing Ayam Cashew 5 Spicy eggplant with homemade sambal sauce Rames VEGA from 11* Sweet chicken with cashew nuts, bell pepper and onions Tahu Petis 10 Nasi Putih* | Kacang Panjang | Sayur Lodeh | Tempe Tahu Tauco 5 Compressed rice cake (lontong) with tofu, Tumis Tahu Tauge | Acar Ketimun | Emping Ayam Semur Betawi 5 Mild spicy tempe and tofu with tauco sauce bean sprouts and petis dressing Sweet chicken thigh with sweet soy sauce Rames CIREBON from 14* Tempe Cabe Ijo 5 Tahu Telor 10.5 Nasi Putih* | Daging Semur Jakarta | Ayam Suwir | Ayam Garing 5 Sweet, spicy fried tempe with green pepper Indonesian omelet filled with tofu and vegetables. Tumis Tahu Tauge | Kacang Panjang | Sambal Goreng Telor Mild spicy crispy chicken thigh Served with homemade peanut sauce dressing | Acar Ketimun | Kerupuk Tempe Kering 5 Ayam Paniki 5 Sweet, crispy tempe Ketoprak 10 Rames KOPI KOPI SPECIAAL from 16* Spicy chicken with lemongrass Vegetarian dish consisting of tofu, vegetables, Nasi Putih* | Ayam Semur Betawi | Daging Rendang | Sambal Goreng Tahu Pete 5 compressed rice cake, rice vermicelli. Served with Sambal Goreng Buncis | Sate Ayam (2 stokjes) | Mild spicy tofu with pete beans in coconut sauce homemade peanut sauce dressing Sambal Goreng Telor | Acar Ketimun | Kerupuk BEEF DISHES PER PORTION Sambal Goreng Telor 1.75 Mie Ayam Istimewa 12.5 Daging Rendang 5.5 Spicy fried egg Thin noodles with chicken (ayam garing / ayam suwir / SOUP Spicy beef in coconut milk ayam paniki / ayam kecap with mushrooms) and vegetables. -

Buffet Hi Tea Tonka Bean Café Deli

BUFFET HI TEA TONKA BEAN CAFÉ DELI SATURDAY Seafood on Ice N.Z. Half Shell Mussels, Poached live Tiger Prawns, Flower Crab Oyster on Crushed Ice Condiments: Lemon wedges, cocktail sauce & Tabasco Cold Platter 2 Types of Homemade Smoked Fish 3 Types of Cold Cuts Japanese Counter Sashimi Fresh Salmon, Tuna, Deluxe selection of Sushi and Maki with Japanese Condiments Condiments: Wasabi, Kikkoman Soya Sauce, Pickled Ginger Appetizer Beef Salad with Local Spices & Mango Salad Gado-Gado with Peanut Sauce Tauhu Sumbat (Beancurd Stuffed with vegetables salad and thai chili sauce) Begedil Ayam Deep fried potato patty Acar Buah Fruit chutney Kerabu Mangga, Kerabu Daging, Kerabu Udang Rojak Buah Keropok Ikan & Papadom Ulam-Ulam empatan Condiments Sambal Belacan, Sambal Tempoyak, Sambal Mangga & Kicap Pedas Manis Cold Selections Mango, Avocado & Green Vegetable Salad Corn, Tomato & Chicken Toast Salad Pineapple with Sausage Salad Thai Green Mango with Prawn Salad Greek salad Toss your own healthy Salad 8 types of Assorted Mesclun Greens 7 types of Sauce & Dressings 8 types of Fresh Assorted Vegetables Salad Caesar Salad Station Romain Lettuce, Grated Parmegano, Crouton, Chopped Beef Strips, Ceasar Dressing Make your own Hot Sandwiches Counter Choice of Tuna, Chicken Mayo, Smoked Salmon, Roasted Beef & Vegetable Confit With cheese, tomato, cucumber, lettuce and dips Antipasti Grilled Mediterranean Vegetables, Roasted Garlic & Shallot Confit Soup Cream of Mushroom Soup With pesto crouton Chinese Herbal Chicken Soup Bread Station with Lavosh, Bread Stick, Butter & Margarine Selection of cheese with condiments Kids Corner Fish Finger French Fries Pisang & Keledek Goreng, Cucur Sayur Pop Corn Candy Floss Cartoon Pancake Waffle with condiments Apam Balik Condiments Tomato ketchup.