Sources: Galileo's Correspondence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunting the White Elephant. When and How Did Galileo

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 97 (1998) Jürgen Renn, Peter Damerow, Simone Rieger, and Michele Camerota Hunting the White Elephant When and how did Galileo discover the law of fall? ISSN 0948-9444 1 HUNTING THE WHITE ELEPHANT WHEN AND HOW DID GALILEO DISCOVER THE LAW OF FALL? Jürgen Renn, Peter Damerow, Simone Rieger, and Michele Camerota Mark Twain tells the story of a white elephant, a present of the king of Siam to Queen Victoria of England, who got somehow lost in New York on its way to England. An impressive army of highly qualified detectives swarmed out over the whole country to search for the lost treasure. And after short time an abundance of optimistic reports with precise observations were returned from the detectives giving evidence that the elephant must have been shortly before at that very place each detective had chosen for his investigations. Although no elephant could ever have been strolling around at the same time at such different places of a vast area and in spite of the fact that the elephant, wounded by a bullet, was lying dead the whole time in the cellar of the police headquarters, the detectives were highly praised by the public for their professional and effective execution of the task. (The Stolen White Elephant, Boston 1882) THE ARGUMENT In spite of having been the subject of more than a century of historical research, the question of when and how Galileo made his major discoveries is still answered insufficiently only. It is mostly assumed that he must have found the law of fall around the year 1604 and that only sev- 1 This paper makes use of the work of research projects of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, some pursued jointly with the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, and the Istituto Nazionale die Fisica Nucleare in Florence. -

The Spectrumspectrum the Calendar 2 Membership Corner 3 the Newsletter for the Buffalo Astronomical a Letter from Mike 4

Inside this issue: TheThe SpectrumSpectrum The Calendar 2 Membership Corner 3 The Newsletter for the Buffalo Astronomical A Letter from Mike 4 Obs Report 5 The Banquet 6 Stay Warm and 9 Cozy Astro Day Poster 11 March/April The Galileo Affair 12 Volume 17, Issue 2 Gallery 18 May Star Chart 19 March Star Chart 19 April Star Chart 20 Our Newly Redesigned Website is Live! If you haven’t checked out BuffaloAstronomy.com recently, it’s time for a visit. Our new site, designed by webmaster and club member Gene Timothy is up and running. The interface is clean and organized and much easier to update with club news and astronomy content. You can now register for the April Banquet, join the club and pay dues using a PayPal account or a major credit card. Coming soon is a new log-in area which will allow members to communicate with each other, share a profile and access special features, including BAA historical information and an archive of Spectrum issues dating back many decades. Come visit and share your comments, thoughts and ideas on how we can make the site better and more useful to the club. A BIG thank you to Gene and the BAA Board for their hard work and creativity! 1 BAA Schedule of Astronomy Fun for 2015 BAA Schedule of Astronomy Fun for 2015 Mar 13: BAA Meeting at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College Mar 20: New Moon Mar 20: Total Solar Eclipse (Arctic) Mar 21-22: Maple Syrup Festival at BMO 9am-3pm Need help for Solar viewing Mar 21: Messier Marathon Dusk till Dawn at Beaver Meadow Observatory Apr 4: First Public Night at Beaver Meadow Observatory April 4: Total Lunar Eclipse Apr 11: BAA Annual Dinner Meeting at Risottos April 18; New Moon Apr 18/19: NEAF who wants to car pool?? April 21-22: Lyrids Meteor Shower Apr 25: Astronomy Day at Buffalo Museum of Science details TBA May 2: Public Night BMO May 8: BAA Meeting at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College May 18: New Moon Jun 6: Public Night BMO Jun 12: BAA Meeting/Elections at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College Jun 17 New Moon July 4: Public Night BMO – I will need help as I have family obligations that day. -

The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(S): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(s): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 2013), pp. 29-36 Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/19654 Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, (2013) Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Nicholas Overgaard “Obedience should be blind and prompt,” Ignatius of Loyola reminded his Jesuit brothers a decade after their founding in 1540.1 By the turn of the seventeenth century, the incumbent Superior General Claudio Aquaviva had reiterated Loyola’s expectation of “blind obedience,” with specific regard to Jesuit support for the Catholic Church during the Galileo Affair.2 Interpreting the relationship between the Jesuits and Copernicans like Galileo Galilei through the frame of “blind obedience” reaffirms the conservative image of the Catholic Church – to which the Jesuits owed such obedience – as committed to its medieval traditions. In opposition to this perspective, I will argue that the Jesuits involved in the Galileo Affair3 represent the progressive ideas of the Church in the early seventeenth century. To prove this, I will argue that although the Jesuits rejected the epistemological claims of Copernicanism, they found it beneficial in its practical applications. The desire to solidify their status as the intellectual elites of the Church caused the Jesuits to reject Copernicanism in public. However, they promoted an intellectual environment in which Copernican studies – particularly those of Galileo – could develop with minimal opposition, theological or otherwise. -

The Harper Anthology of Academic Writing

The Harper P\(\·::�·::::: ...:.:: .� : . ::: : :. �: =..:: ..·. .. ::.:·. · ..... ·.' · .· Anthology of . ;:·:·::·:.-::: Academic Writing S T U D E N T A U T H 0 R S Emily Adams Tina Herman Rosemarie Ruedi Nicole Anatolitis Anna Inocencio Mary Ellen Scialabba Tina Anatolitis Geoff Kane Jody Shipka Mario Bartoletti David Katz Susan Shless Marina Blasi Kurt Keifer Carrie Simoneit Jennifer Brabec Sherry Kenney Sari Sprenger Dean Bushek Kathy Kleiva Karen Stroehmann Liz Carr Gail Kottke Heather To llerson Jennifer Drew-Steiner Shirley Kurnick Robert To manek Alisa Esposito Joyce Leddy Amy To maszewski Adam Frankel James Lee Robert Van Buskirk Steve Gallagher Jan Loster Paula Vicinus Lynn Gasier Martin Maney Hung-Ling Wan Christine Gernady Katherine Marek Wei Weerts ·:-::::·:· Joseph L. Hazelton Philip Moran Diana Welles Elise Muehlhausen Patty Werber Brian Ozog Jimm Polli Julie Quinlan Santiago Ranzzoni Heidi Ripley I S S U E V I I 1 9 9 5 The Harper Anthology of Academic Writing Issue VII 1995 \Y/illiam Rainey Harper College T h e Harper Anthology Emily Adams "Manic Depression: a.k.a. Bipolar Disorder" Table (Psychology) 1 Nicole Anatolitis, Tina Anatolitis, Lynn Gasier and Anna Inocencio "Study Hard" of (Reading) 7 Mario Bartoletti "Zanshin: Perfect Posture" Contents (English) 8 Marina Blasi "To Parent or Not to Parent ... That Is the Question (English) 11 Jennifer Brabec "Nature Journal" (Philosophy) 15 Dean Bushek "A Piece of My Life" (English) 17 Liz Carr "Betrayal" (English) 20 Jennifer Drew-Steiner "First Exam: Question Four" (Philosophy) 24 Alisa Esposito "The Trouble with Science" (English) 25 Adam Frankel "Form, Subject, Content" (Art) 27 Table of Contents Steve Gallagher Joyce Leddy "Galileo Galilei" "Is Good Design A Choice?" (Humanities) 28 (Interior Design) 62 Christine Gernady James Lee "Stresses of Office Work, Basic Causes "Scientific Integrity" and Solutions" (Physics) 63 (Secretarial Procedures) 34 Jan Loster Joseph L. -

Words of Thanks by Dan Sapone

Words of Thanks By Dan Sapone “And yet it moves" (in the original Italian: “Eppur si muove”) — Galileo Galilei, Gentleman of Florence = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = "The Sun, with all its planets revolving around it and depending upon it, still can find the time to ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do." — Galileo Galilei, 1632 This line first captured my imagination when I saw it on the back label of a bottle of red wine (where else would I look for memorable, meaningful words, eh?). I was looking for some wine for our Thanksgiving dinner table, the family was going to be there, and I would be offering a Thanksgiving Toast — I thought these words were perfect. When the time came, with the bottle in my hand I mentioned that we all have so much to be thankful for: our families, our homes, the work we do, the people who are kind to us, the food and wine we enjoy, and the good times we have. Then, using Galileo’s words, I gave thanks for The Sun, representing all of the ‘greater powers’ that contribute to all of that goodness — whatever and whomever they might be. The words were fun, appropriate to the occasion, and they brought smiles. We lifted our glasses and said “Thanks’ to each other. Galileo’s words helped us do that. A Random Bunch of Thanksgiving Photos “And yet it moves.” Thanksgiving, 2017 Page 1 of 4 Galileo’s Words In Context So, if we let our minds drift back 385 years to Galileo’s time, we learn that he caused quite a kerfuffle, to say the least, when he first used these words. -

Galileo and Bellarmine

The Inspiration of Astronomical Phenomena VI ASP Conference Series, Vol. 441 Enrico Maria Corsini, ed. c 2011 Astronomical Society of the Pacific Galileo and Bellarmine George V. Coyne, S.J. Vatican Observatory, Vatican City State Abstract. This paper aims to delineate two of the many tensions which bring to light the contrasting views of Galileo Galilei and of Cardinal Robert Bellarmine with respect to the Copernican-Ptolemaic controversies of the 16th and 17th centuries: their respective positions on Aristotle’s natural philosophy and on the interpretation of Sa- cred Scripture. Galileo’s telescopic observations, reported in his Sidereus Nuncius, were bringing about the collapse of Aristotle’s natural philosophy and he taught that there was no science in Scripture. 1. Introduction This paper investigates the tensions between two of the principal protagonists in the controversies involved in the birth of modern science, Galileo Galilei and Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, and how they were resolved or not in a spirit of accommodation. Bellarmine’s fellow Jesuits at the Roman College confirmed Galileo’s Earth-shaking observations, reported in his Sidereus Nuncius. Aristotle’s physics was crumbling. Would Aristotelian philosophy, which was at the service of theology, also collapse? Controversies over the nature of sunspots and of comets seemed to hold implications for the very foundations of Christian belief. Some Churchmen saw the threat and faced it with an astute view into the future; others, though pioneers as scientists, could not face the larger implications of the scientific revolution to which they with Galileo con- tributed. Much of what occurred can be attributed to the strong personalities of the individual antagonists and Bellarmine will prove to be one of the most important of those personages. -

Article De Fond, Réalisation

ARTICLE DE FOND, RÉA LISATION QUATOR PLANETIS CIRCUM IOVIS : MEDICEA SIDERA Pierre Le Fur (MPSI, Institut Supérieur d'Électronique et du Numérique Toulon, formateur académique en astronomie –Nice) Résumé : Suivons les traces de Galilée en étudiant ses observations sur les quatre satellites médicéens de Jupiter telles qu’elles furent décrites dans le "sidereus nuncius". Nous montrerons qu’à partir de ces relevés on peut retrouver certaines lois ignorées du savant Toscan. Enfin nous proposerons la construction d’un "Jovilab" qualitatif, sorte de tables d’éphémérides de positions de ces quatre satellites. Si, en l’an de grâce 2009, nous souhaitons fêter quasi impossible à déterminer, aurait été dignement l’Année Mondiale de l’Astronomie, immédiate par simple différence entre l’heure la lecture de " sidereus nuncius ", œuvre solaire locale et cette "heure universelle jo- étincelante de Galileo Galilei, s’impose à nous. vienne"; cela aurait constitué une deuxième Elle constitue l’allumette déclenchant l’incendie révolution, moins intellectuelle mais économi- qui embrasa la physique aristotélicienne et ses quement et militairement exceptionnelle. partisans religieux. Les observations récoltées par Galilée pendant Cette œuvre peut être facilement consultée sur les années qui suivirent la publication de le site de l’Université de Strasbourg à "sidereus nuncius " lui permettront d’obtenir un l’adresse [10]. La force et la simplicité de cet outil de prévisions de la position de ces ouvrage apparaît d’emblée, même si l’on ignore satellites : le Jovilab. tout du latin… Les gravures intégrées au texte Je vous propose de suivre les traces de Galilée ; nous suggèrent autant le contenu des d’examiner ses observations médicéennes ; de découvertes décrites par Galilée que le génie de montrer comment on peut retrouver certaines son interprétation. -

C:\Data\WP\F\200\Catalogue Sections\Aaapreliminary Pages.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 200 Proofs Science, Medicine, Natural History, Bibliography, & Much More Introduction & Selective Subject Index on Following Pages Introduction TWO HUNDRED CATALOGUES in thirty-three years: more than 35,000 books and manuscripts have been described in these catalogues. Thousands of other books, including many of the most important and unusual, never found their way into my catalogues, having been quickly sold before their descriptions could appear in print. In the last fifteen years, since my Catalogue 100 appeared, many truly exceptional books passed through my hands. Of these, I would like to mention three. The first, sold in 2003 was a copy of the first edition in Latin of the Columbus Letter of 1493. This is now in a private collection. In 2004, I was offered a book which I scarcely dreamed of owning: the Narratio Prima of Rheticus, printed in 1540. Presenting the first announcement of the heliocentric system of Copernicus, this copy in now in the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri. Both of the books were sold before they could appear in my catalogues. Finally, the third book is an absolutely miraculous uncut copy in the original limp board wallet binding of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Appearing in my Catalogue 178, this copy was acquired by the Library of Congress. This is the first and, probably the last, “personal” catalogue I will prepare. -

Recieved Notice Today That It Did Not Go Through

Scientists are People, Too: Biographies of Astronomical Scientists as a Literary Introduction to the Heliocentric Theory Autry McMorris Welch Middle School INTRODUCTION The Setting and Objectives One of the teaching tools that teachers often use is to take advantage of their students’ prior knowledge. This allows students to connect with the author or subject. Many students have had astronomical awareness or experiences as simple as Aristotle’s in 320 BC – that the Earth must be round because it casts a crescent shape on the moon. For me, it was an incidental thing that I sometimes noticed the moon out in the mornings and evenings when I walked my dogs. Almost as a type of entertainment, I started to anticipate where the moon would be positioned on my next walk. I found myself exhilarated as I could correctly anticipate its position. The key for me was that the moon was moving west, but because of the Earth’s rotation, it appeared to be moving east. At that moment, I shared an icon of truth with the great masters. Astronomy is very complex, to say the least. Some students, aware of their limitations, would not begin to broach the subject except from a non-threatening position. What if an introductory course were to be available that introduced the periphery of the subject? What if selected writings, biographies, autobiographies, theories and the like were a part of a curriculum to superimpose our literary devices of today on great works that were written hundreds of years ago? Copernicus described himself somewhat as candid and clear enough that both the unlearned as well as the learned might see that he was not seeking to flee from the judgment of any man, even if someone provided a guard against the bites of slanderers, the proverb holds that there is no medicine for the bite of a sycophant. -

Operations of the Geometric and Military Compass

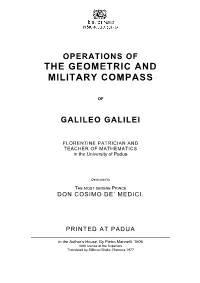

OPERATIONS OF THE GEOMETRIC AND MILITARY COMPASS OF GALILEO GALILEI FLORENTINE PATRICIAN AND TEACHER OF MATHEMATICS in the University of Padua Dedicated to THE MOST SERENE PRINCE DON COSIMO DE’ MEDICI. PRINTED AT PADUA in the Author’s House, By Pietro Marinelli. 1606 With license of the Superiors Translated by Stillman Drake, Florence 1977 CONTENTS Dedication............................................................................................................................ 5 Prologue .............................................................................................................................. 6 Operation I Division of a line .................................................................................................................. 7 Operation II How in any given line we can take as many parts as may be required .............................. 8 Operation III How these same lines give us two, and even infinitely many, scales for altering one map into another larger or smaller ............................................................................... 8 Operation IV The rule-of-three solved by means of a compass and these same Arithmetic Lines .................................................................................................................................... 9 Operation V The inverse rule-of-three resolved by means of the same lines ......................................... 10 Operation VI Rule for monetary exchange .............................................................................................. -

Here from the Main Rings to Enceladus M.K

Block Schedule Wednesday 7/27 Thursday 7/28 Friday 7/29 8:30 Introduction 8:40 Ring Objects 9:00 Dense Ring Ring 9:20 Structure Composition 9:40 10:00 10:20 10:40 Dense Ring Ring F ring 11:00 Structure Particle 11:20 (continued) Properties 11:40 12:00 12:20 12:40 Lunch Lunch 13:00 Lunch 13:20 13:40 14:00 Ring Particle Ring Origins 14:20 Sizes 14:40 Dusty Rings 15:00 OPUS 15:20 15:40 Intro to Posters Ring 16:00 Dusty Rings Evolution 16:20 and 16:40 Ring Environments Poster 17:00 Session 17:20 Discussion Discussion 17:40 18:00 18:30 19:00 Dinner on Campus BBQ at Treman Park Open 19:30 2 Wedsneday Morning, July 27 8:30-8:40 Welcome, Introduction 8:40-9:00 Revisiting the Self-Gravity Wakes Granola Bar Model: More Data, More Parameters J. E. Colwell, R. G. Jerousek, J. H. Cooney 9:00-9:20 Self-Gravity Wakes and the Viscosity of Dense Planetary Rings G. R. Stewart 9:20-9:40 B Ring Gray Ghosts in Cassini UVIS Occultations M. Sremˇcevi´c L.W. Esposito, J.E. Colwell, N. Albers 9:40-10:00 Simulating the B ring M. Lewis 10:00-10:20 Break 10:20-10:40 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: I. The Cassini Division R. G. French, P. D. Nicholson, J. Colwell, E. A. Marouf, N. J. Rappaport, M. Hedman, K. Lonergan, C. McGhee-French, and T. Sepersky 10:40-11:00 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: II. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Original Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days / Angelini, Emma; Grassini, Sabrina; Parvis, Marco; Parvis, Luca; Gori, Andrea. - ELETTRONICO. - (2020), pp. 1-6. ((Intervento presentato al convegno 15th IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications - MeMeA2020 tenutosi a Bari, Italy nel 1-3 June 2020 [10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339]. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2841349 since: 2020-08-25T14:41:07Z Publisher: IEEE Published DOI:10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright IEEE postprint/Author's Accepted Manuscript ©2020 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating new collecting works, for resale or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works. (Article begins on next page) 07 October 2021 Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Emma Angelini Sabrina Grassini Department of Applied Science and Technology Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Politecnico di Torino Torino, Italy Torino, Italy [email protected]