Syria, April 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Dissertation-Master-Cover Copy

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67x11827 Author Abu-Rish, Ziad Munif Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish 2014 © Copyright by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTAITON Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation broadens the inquiry into the history of state formation, economic development, and popular mobilization in Lebanon during the early independence period. The project challenges narratives of Lebanese history and politics that are rooted in exceptionalist and deterministic assumptions. It does so through an exploration of the macro-level transformations of state institutions, the discourses and practices that underpinned such shifts, and the particular series of struggles around Sharikat Kahruba Lubnan that eventual led to the nationalization of the company. The dissertation highlights the ways in which state institutions during the first decade of independence featured a dramatic expansion in both their scope and reach vis-à-vis Lebanese citizens. Such shifts were very much shaped by the contexts of decolonization, the imperatives of regime consolidation, and the norms animating the post-World War II global and regional orders. -

The Dynamics of Syria's Civil

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. RAND perspectives (PEs) present informed perspective on a timely topic that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND perspectives undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Perspective C O R P O R A T I O N Expert insights on a timely policy issue The Dynamics of Syria’s Civil War Brian Michael Jenkins Principal Observations One-third of the population has fled the country or has been displaced internally. -

Next Steps in Syria

Next Steps in Syria BY JUDITH S. YAPHE early three years since the start of the Syrian civil war, no clear winner is in sight. Assassinations and defections of civilian and military loyalists close to President Bashar Nal-Assad, rebel success in parts of Aleppo and other key towns, and the spread of vio- lence to Damascus itself suggest that the regime is losing ground to its opposition. The tenacity of government forces in retaking territory lost to rebel factions, such as the key town of Qusayr, and attacks on Turkish and Lebanese military targets indicate, however, that the regime can win because of superior military equipment, especially airpower and missiles, and help from Iran and Hizballah. No one is prepared to confidently predict when the regime will collapse or if its oppo- nents can win. At this point several assessments seem clear: ■■ The Syrian opposition will continue to reject any compromise that keeps Assad in power and imposes a transitional government that includes loyalists of the current Baathist regime. While a compromise could ensure continuity of government and a degree of institutional sta- bility, it will almost certainly lead to protracted unrest and reprisals, especially if regime appoin- tees and loyalists remain in control of the police and internal security services. ■■ How Assad goes matters. He could be removed by coup, assassination, or an arranged exile. Whether by external or internal means, building a compromise transitional government after Assad will be complicated by three factors: disarray in the Syrian opposition, disagreement among United Nations (UN) Security Council members, and an intransigent sitting govern- ment. -

Herding, Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence

Herding,Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence* Yiming Cao† Benjamin Enke‡ Armin Falk§ Paola Giuliano¶ Nathan Nunn|| 7 September 2021 Abstract: According to the widely known ‘culture of honor’ hypothesis from social psychology, traditional herding practices have generated a value system conducive to revenge-taking and violence. We test the economic significance of this idea at a global scale using a combination of ethnographic and folklore data, global information on conflicts, and multinational surveys. We find that the descendants of herders have significantly more frequent and severe conflict today, and report being more willing to take revenge in global surveys. We conclude that herding practices generated a functional psychology that plays a role in shaping conflict across the globe. Keywords: Culture of honor, conflict, punishment, revenge. *We thank Anke Becker, Dov Cohen, Pauline Grosjean, Joseph Henrich, Stelios Michalopoulos and Thomas Talhelm for useful discussions and/or comments on the paper. †Boston University. (email: [email protected]) ‡Harvard University and NBER. (email: [email protected]) §briq and University of Bonn. (email: [email protected]) ¶University of California Los Angeles and NBER. (email: [email protected]) ||Harvard University and CIFAR. (email: [email protected]) 1. Introduction A culture of honor is a bundle of values, beliefs, and preferences that induce people to protect their reputation by answering threats and unkind behavior with revenge and violence. According to a widely known hypothesis, that was most fully developed by Nisbett( 1993) and Nisbett and Cohen( 1996), a culture of honor is believed to reflect an economically-functional cultural adaptation that arose in populations that depended heavily on animal herding (pastoralism).1 The argument is that, relative to farmers, herders are more vulnerable to exploitation and theft because their livestock is a valuable and mobile asset. -

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(S): C

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(s): C. Ernest Dawn Source: Middle East Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1962), pp. 145-168 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4323468 Accessed: 27/08/2009 15:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mei. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal. http://www.jstor.org THE RISE OF ARABISMIN SYRIA C. Ernest Dawn JN the earlyyears of the twentiethcentury, two ideologiescompeted for the loyalties of the Arab inhabitantsof the Ottomanterritories which lay to the east of Suez. -

The Syrian Civil War a New Stage, but Is It the Final One?

THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR A NEW STAGE, BUT IS IT THE FINAL ONE? ROBERT S. FORD APRIL 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-8 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * 1 INTRODUCTION * 3 BEGINNING OF THE CONFLICT, 2011-14 * 4 DYNAMICS OF THE WAR, 2015-18 * 11 FAILED NEGOTIATIONS * 14 BRINGING THE CONFLICT TO A CLOSE * 18 CONCLUSION © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY Eight years on, the Syrian civil war is finally winding down. The government of Bashar al-Assad has largely won, but the cost has been steep. The economy is shattered, there are more than 5 million Syrian refugees abroad, and the government lacks the resources to rebuild. Any chance that the Syrian opposition could compel the regime to negotiate a national unity government that limited or ended Assad’s role collapsed with the entry of the Russian military in mid- 2015 and the Obama administration’s decision not to counter-escalate. The country remains divided into three zones, each in the hands of a different group and supported by foreign forces. The first, under government control with backing from Iran and Russia, encompasses much of the country, and all of its major cities. The second, in the east, is in the hands of a Kurdish-Arab force backed by the U.S. The third, in the northwest, is under Turkish control, with a mix of opposition forces dominated by Islamic extremists. The Syrian government will not accept partition and is ultimately likely to reassert its control in the eastern and northwestern zones. -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

Houses Built on Sand Ii

i Houses built on sand ii Series editors: Simon Mabon, Edward Wastnidge and May Darwich After the Arab Uprisings and the ensuing fragmentation of regime– society relations across the Middle East, identities and geopolitics have become increasingly contested, with serious implications for the ordering of political life at domestic, regional and international levels, best seen in conflicts in Syria and Yemen. The Middle East is the most militarised region in the world, where geopolitical factors remain predominant in shaping political dynamics. Another common feature of the regional landscape is the continued degeneration of communal relations as societal actors retreat into substate identities, while difference becomes increasingly violent, spilling out beyond state borders. The power of religion – and trans- state nature of religious views and linkages – thus provides the means for regional actors (such as Saudi Arabia and Iran) to exert influence over a number of groups across the region and beyond. This series provides space for the engagement with these ideas and the broader political, legal and theological factors to create space for an intellectual reimagining of socio- political life in the Middle East. Originating from the SEPAD project (www.sepad.org.uk), this series facilitates the reimagining of political ideas, identities and organisation across the Middle East, moving beyond the exclusionary and binary forms of identity to reveal the contingent factors that shape and order life across the region. iii Houses built on sand Violence, sectarianism and revolution in the Middle East Simon Mabon Manchester University Press iv Copyright © Simon Mabon 2020 The right of Simon Mabon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Aramaeans Outside of Syria 1. Assyria Martti Nissinen 1. Aramaeans

CHAPTER NINE OUTLOOK: ARAMAEANS OUTSIDE OF SYRIA 1. Assyria Martti Nissinen 1. Aramaeans and the Neo-Assyrian Empire (934–609 B.C.)1 Encounters between the Aramaeans and the Assyrians are as old as is the occupation of these two ethnic entities in the area between the Tigris and the Khabur rivers and in northern Mesopotamia. The first occurrence of the word ar(a)māyu in the Assyrian records is to be found in the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 B.C.), who gives an account of his confronta- tion with the “Aramaean Aḫlamaeans” (aḫlamû armāya) along the Middle Euphrates;2 however, the presence of the Aramaean tribes in this area is considerably older.3 The Assyrians had governed the Khabur Valley in the 13th century already, but the movement of the Aramaean tribes from the west presented a constant threat to the Assyrian supremacy in the area. Tiglath-Pileser I and his follower, Aššur-bēl-kala (1073–1056 B.C.), fought successfully against the Aramaeans, but in the long run, the Assyrians were not able to maintain control over the Lower Khabur–Middle Euphrates region. Assur-dān (934–912 B.C.) and Adad-nirari II (911–891 B.C.) man- aged to regain the area between the Tigris and the Khabur occupied by the Aramaeans, but the Khabur Valley was never under one ruler, and even the campaigns of Assurnasirpal II (883–859 B.C.) did not consolidate the Assyrian dominion. Under Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.) the area east of the Euphrates came under Assyrian control, but it was not until the 1 I would like to thank the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ, USA) for the opportunity of writing this article during a research visit in May–June, 2011. -

Syria Situation

SYRIA SITUATION The Syria situation entered its tenth year in 2020 with more than 5.5 million Syrian refugees hosted by neighbouring countries, of whom 45% are children and 21% are women. Living conditions are precarious, with more than UNHCR’s overall requirements for the Syria 60% of Syrian refugees living in poverty. UNHCR situation in 2020 stand at $1.991 billion. As of 25 and UNDP continue to co-lead the Regional August 2020, $684.9 million have been received. Refugee and Resilience Plan in response to the Flexible and country-level funds received by Syria crisis (3RP), coordinating the work of more UNHCR have allowed the organization to allocate than 270 partners in the five main hosting an additional $66.4 million to the Syria situation, countries. Inside the Syrian Arab Republic (Syria), raising the current funding level to 38%. These SYRIA UNHCR continues to support IDPs through low funding levels have forced UNHCR’s protection activities, core relief items and shelter operations in neighbouring countries to cut or SITUATION activities, while also mobilizing emergency reduce some programmes. Further cuts are responses to new displacement. expected in the second half of 2020 if more funding is not received. Three siblings walk with their father through the rubble of their neighbourhood in Homs. UNHCR/VIVIAN TOU’MEH © AFFECTED COUNTRIES KEY POPULATION DATA $1.991 BILLION (AS OF 30 JUNE 2020) UNHCR's financial requirements 2020, as of 25 August 2020 5.5 million Funding shortfall Syrian refugees and asylum- $1.240 BILLION TURKEY -

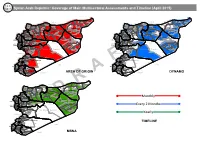

Monthly Every 2 Months Yearly

Syrian Arab Republic: Coverage of Main Multisectoral Assessments and Timeline (April 2015) Al-Malikeyyeh Al-Malikeyyeh Turkey Turkey Quamishli Quamishli Jarablus Jarablus Ras Al Ain Ras Al Ain Afrin Ain Al Arab Afrin Ain Al Arab Azaz Tell Abiad Azaz Tell Abiad Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al-Hasakeh Harim Harim Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Menbij Menbij Aleppo Aleppo Ar-Raqqa Idleb Ar-Raqqa Idleb Jisr-Ash-Shugur Jisr-Ash-Shugur As-Safira Ariha As-Safira Lattakia Ariha Ath-Thawrah Lattakia Ath-Thawrah Al-Haffa Idleb Al-Haffa Idleb Deir-ez-Zor Al Mara Deir-ez-Zor Al-Qardaha Al Mara Al-Qardaha As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia Jablah Jablah Muhradah Muhradah As-Salamiyeh As-Salamiyeh Hama Hama Banyas Banyas Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Tartous Tartous Dreikish Al Mayadin Dreikish Ar-Rastan Al Mayadin Ar-Rastan Tartous TartousSafita Al Makhrim Safita Al Makhrim Tall Kalakh Tall Kalakh Homs Syrian Arab Republic Homs Syrian Arab Republic Al-Qusayr Al-Qusayr Abu Kamal Abu Kamal Tadmor Tadmor Homs Homs Lebanon Lebanon An Nabk An Nabk Yabroud Yabroud Al Qutayfah Al Qutayfah Az-Zabdani Az-Zabdani At Tall At Tall Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Damascus Damascus Darayya Darayya Duma Duma Qatana Qatana Rural Damascus Rural Damascus IraqIraq IraqIraq Quneitra As-Sanamayn Quneitra As-Sanamayn Dar'a Quneitra Dar'a Quneitra Shahba Shahba Al Fiq Izra Al Fiq Izra As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida Dara Jordan AREA OF ORIGIN Dara Jordan