Tenth Quarterly Report Part 1 – Eastern Ghouta February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/515 安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 日至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日和 31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 6 月 27 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-56095 (C) 231012 241012 *1256095C* S/2012/515 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [Original: Arabic] Wednesday, 27 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 27 June 2012 at 2200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in the area of Qastal. 2. At 0200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in the vicinity of the Industry School in Ra's al-Nab‘, Qatana. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group attacked and detonated explosive devices at the Syrian Ikhbariyah satellite channel building in Darwasha in the vicinity of Khan al-Shaykh, killing Corporal Ma'mun Awasu, Conscript Tal‘at al-Qatalji, Conscript Mash‘al al-Musa and Conscript Abdulqadir Sakin. Several employees were also killed, including Sami Abu Amin, Muhammad Shamsah and employee Zayd Ujayl. Another employee was wounded , 11 law enforcement officers were abducted, and 33 rifles were seized. 4. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group opened on fire on and fired rocket-propelled grenades at a law enforcement checkpoint in Hurnah between Ma‘araba bridge and Tall. -

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

FSS Wos Response Analysis

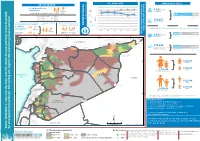

SO1 RESPONSE MARCH 2017 CYCLE Y PEOPLE IN NEED N I 8 B G Food & Livelihood 7.0 7.0 7.0 I 9 7 6.3 6.3 6.3 5.38million Assistance HED OR Food Basket Million C e 6 l Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 6.16 D SO1 5.8 5.89 5.78 5 N 4 M m 1.16.338m M 5.38 3.35 Target REA September 2015 8.7 Million 5.15 A From within Syria From neighbouring e 4 countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA ES ES Million peop I nc September 2016 9.0 Million 129,657 3 Cash and Voucher ITI LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING AR ta OVERALL TARGET MARCH 2017 RESPONSE 2 BENEFICIARIES Reached s FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher i Beneficiaries 1 Food Basket, ICI Cash & Voucher - ODAL Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided ss 7 EF 5.38 0 life sustaining Million M 9 Million OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR N a E nsecure Million Emergency i d B 2 Response (77%) of SO1 Target o 608,654 1.84 M Million Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.45million From within Syria From neighbouring od 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E Bread-Flour fo countries 7 7 o c 1 Cizre- f 1 0 g! i 0 ng 2 Nusaybin-Al i 2 Kiziltepe-Ad l T U R K E Y Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y Darbasiyah n Ayn al g! ! g! h g Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras c b Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya 170,555 r Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa tai Akcakale-Tall ! Emergency Response with 116,265 a g! g! g g! 54,290 u Bab As Abiad Ready to Eat Ration From neighbouring M Salama Cobanbey g! From within Syria - countries ssessed g! g! p sus ) a 1 t e Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H fe -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

Blitzkrieg: the Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht's

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2021 Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era Briggs Evans East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Briggs, "Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3927. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3927 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ______________________ by Briggs Evans August 2021 _____________________ Dr. Stephen Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry Antkiewicz Dr. Steve Nash Keywords: Blitzkrieg, doctrine, operational warfare, American military, Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, World War II, Cold War, Soviet Union, Operation Desert Storm, AirLand Battle, Combined Arms Theory, mobile warfare, maneuver warfare. ABSTRACT Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era by Briggs Evans The evolution of United States military doctrine was heavily influenced by the Wehrmacht and their early Blitzkrieg campaigns during World War II. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

Hard Offensive Counterterrorism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2019 The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism Daniel Thomas Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Thomas, Daniel, "The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism" (2019). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2101. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2101 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF FORCE: HARD OFFENSIVE COUNTERTERRORISM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DANIEL THOMAS B.A., The Ohio State University, 2015 2019 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Defense Date: 8/1/19 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel Thomas ENTITLED The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _______________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Thesis Director ________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ______________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. -

Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals

Documentation of 72 Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals Identifying 801 Individuals Who Appeared in Caesar Photographs, the US Congress Must Pass the Caesar Act to Provide Accountability Monday, October 21, 2019 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R190912 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction and methodology of the report II. The Syrian Network for Human Rights’ cooperation with the UN Rapporteur on deaths due to Torture III. The toll of victims who died due to torture according to the SNHR’s database IV. The most notable methods of torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers Physical torture Health neglect, conditions of detention and deprivation Sexual violence Psychological torture and humiliation of human dignity Forced labor Torture in military hospitals Separation V. New identification of 29 individuals who appeared in Caesar photographs leaked from military hospitals VI. Examples of individuals shown in Caesar photographs who we were able to identify VII. Various testimonies of torture incidents by survivors of the Syrian regime’s detention centers VIII. The most notable individuals responsible for torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers according to the SNHR’s database IX. Conclusions and recommendations 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org I. Introduction and methodology of the report: Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have been subjected to abduction (detention) by Syrian Regime forces; according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights’ (SNHR) database, at least 130,000 individuals are still detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime since the start of the popular uprising for democracy in Syria in March 2011. -

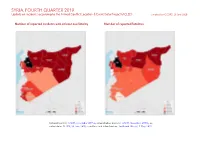

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen.