Teaching the Japanese American Experience: an Educator's Tool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amache Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary

Annotated Resource Set (ARS) Amache Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary Title/Content Area: Amache /US History Developed by: Kelly Jones-Wagy Grade Level: 9-12 Contextual Paragraph During World War II, 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps—including one in southeastern Colorado called the Granada Relocation Center, or “Amache.” Camp Amache was one of ten War Relocation Authority, or internment, camps where US authorities forced Japanese Americans to live after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Home to nearly 7,300 internees from 1942 to 1945, Amache now is a National Historic Landmark. Governor Ralph L. Carr took an unpopular stance, inviting Japanese Americans to stay in Colorado after the war and publicly stating his opinion that internment was unconstitutional. Amache officially closed in October 1945 following the end of World War II. However, for many of the Japanese internees, there was no home to return to. Some chose to stay in Colorado, as they were welcomed by Governor Carr. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, awarding $20,000 to every surviving internee and essentially apologizing for the internment process. 1 Resource Set Title Letter from Governor Letter from Robert D. Executive Order 9066 Map of Concentration Battle Honors for the Ralph Carr to Mrs. J.A. Elder to Governor Camps 442nd Hughes Ralph Carr Description March 6, 1942‐ March 1, 1942‐State February 19, 1942‐ Map shows where the Two letters from Governor Carr Senator Robert Elder President Roosevelt 10 relocation centers generals in 1945 responds to a woman requests that the uses executive power were located in the outlining the in La Junta who is governor refuse to to confine people of United States, their distinguished concerned that the allow the Japanese Japanese descent for populations, and the performance and internment camp is into Colorado and the duration of the type of each center. -

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

The Voices of Children: Re-Imagining the Internment of Japanese Americans Through Poetry

Social Studies and the Young Learner 25 (4), pp. 30–32 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies The Voices of Children: Re-imagining the Internment of Japanese Americans through Poetry Elizabeth M. Frye and Lisa A. Hash In this article, we describe just one activity from an interdisciplinary social justice unit1 taught to two fifth-grade social studies classes with the use of Cynthia Kadohata’s multicultural historical fiction novel Weedflower.2 Often, our younger students feel their voices are silenced...their messages are not heard. Like many of our fifth-grade students, the main characters in Kadohata’s novel are marginalized peoples whose voices were kept silent during a time of war hysteria. In this historical novel, Sumiko, a young Japanese American girl and her family are forced to relocate to Poston Internment Camp after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Poston, located in southwestern Arizona, was the largest of the ten internment camps (or “prison camps,” as many of its former residents called it) operated by the U.S. government during World War II. While at Poston, Sumiko befriends Frank, a young Mojave Indian who lives on the neighboring reservation. The Constitution’s Promises and Principles American was ever found guilty of endangering the U.S. during While learning about the internment camps, students also learn World War II. (Indeed, President Roosevelt recognized that the about the U.S. Constitution—how its promises were first violated, then-territory of Hawaii would collapse without its business and then, many years later, partially redeemed. leaders, administrators, engineers, and other civil servants—most The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution states, of whom were of Japanese American descent. -

WW2 Timeline QR Coded

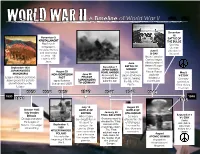

WORLD WAR II A Timeline of World War II December 16 November 9 BATTLE OF KRISTALLNACHT THE BULGE Nazi’s torch Last big synagogues, German vandalize homes June 6 offensive in and businesses D-DAY the west. of Jews - kill Secret Operation close to 100 Overlord begins. Jews June Allied invasion of BATTLE OF Western Europe - September 1931 December 7 MIDWAY Normandy, JAPAN INVADES JAPAN BOMBS August 23 PEARL HARBOR U.S defeats France. France MANCHURIA May 9 NON AGGRESSION June 22 As a result, the Japan at Midway would be V-E DAY FRANCE League of Nations protested. PACT United States Islands, turning liberated 3 Germany Japan ignored the protests signed between SURRENDERS joins the war months later TO GERMANY the tide in the surrenders. and withdrew from the German and USSR Pacific. Allied victory League in Europe 1935 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1944 1930 1946 1931 1945 July 10 August 23 October 1935 BATTLE OF BATTLE OF Italy Invades BRITAIN January 20 STALINGRAD Ethiopia FINAL SOLUTION September 2 Hitler begins Germany V-J DAY Ethiopia protests to bombing Britain in Germans meet to attacks the city discuss the 'Final Japan the League of his quest to of Stalingrad. surrenders. September 1, solution of the Nations. The League conquer the Five months American does nothing 1939 Jewish Question'. country. Britain The 'Final later, Germany victory over HITLER INVADES never surrenders surrenders Japan. POLAND solution' was a August and after more code name for This marks the ATOMIC BOMBS than a year Hitler the murder of all beginning of World gives up. -

Grade 6 Social Studies Canada: a Country of Change (1867 to Present)

Grade 6 Social Studies Canada: A Country of Change (1867 to Present) A Foundation for Implementation GRADE 6 SOCIAL STUDIES CANADA: A COUNTRY OF CHANGE (1867 TO PRESENT) A Foundation for Implementation 2006 Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth Cataloguing in Publication Data 372.8971 Grade 6 social studies : Canada : a country of change (1867 to present) : a foundation for implementation Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-7711-3581-1 ISBN-10: 0-7711-3581-5 1. Canada—History—1867- —Study and teaching (Elementary). 2. Social sciences—Study and teaching (Elementary). 3. Social sciences—Study and teaching (Elementary)—Manitoba. I. Manitoba. Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth. II. Title: Canada : a country of change (1867 to present) : a foundation for implementation. Copyright © 2006, the Crown in Right of Manitoba as represented by the Minister of Education, Citizenship and Youth. Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth, School Programs Division, 1970 Ness Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3J 0Y9. Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Sincere thanks to the authors and publishers who allowed their original material to be adapted or reproduced. Some images © 2006 www.clipart.com GRADE Acknowledgements 6 Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following individuals in the development of Grade 6 Social Studies: Canada: A Country of Change (1867 to Present): A Foundation for Implementation. Manitoba Framework Development Team Kindergarten to Grade 4 Norma Armstrong Bairdmore School Pembina Trails S.D. -

C H a P T E R 25 World War II

NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 826 CHAPTER 25 World War II This World War II poster depicts the many nations united in the fight against the Axis powers. In reality there were often disagreements. Notice that to the right, the American sailor is marching next to Chinese and Soviet soldiers. Within a few years after victory, they would be enemies. (University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library) American Stories A Native American Boy Plays at War N. Scott Momaday, a Kiowa Indian born in Lawton, Oklahoma, in 1934, grew up on Navajo,Apache, and Pueblo reservations. He was only 11 years old when World War II ended, yet the war had changed his life. Shortly after the United States entered the war, Momaday’s parents moved to New Mexico, where his father got a job with an oil company and his mother worked in the civilian personnel office at an army air force 826 NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 827 CHAPTER OUTLINE base. Like many couples, they had struggled through the hard times of the Depression. The Twisting Road to War The war meant jobs. Foreign Policy in a Global Age Momaday’s best friend was Billy Don Johnson, a “reddish, robust boy of great good Europe on the Brink of War humor and intense loyalty.” Together they played war, digging trenches and dragging Ethiopia and Spain themselves through imaginary minefields. They hurled grenades and fired endless War in Europe rounds from their imaginary machine guns, pausing only to drink Kool-Aid from their The Election of 1940 canteens.At school, they were taught history and math and also how to hate the enemy Lend-Lease and be proud of America. -

A Conversation on Japanese American Incarceration & Its Relevance to Today

CONVERSATION KIT Courtesy of the National Archives Tuesday, May 17, 2016 1:00-2:00 pm EDT, 10:00-11:00 am PDT Smithsonian National Museum of American History Kenneth E. Behring Center IN WORLD WAR II NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT . 3 Introduction . 3 Program Details . 4 Regional Summit Locations . 4 When, Where, and How to Participate . 4 Join the Conversation . 5 Central Questions . 6 Panelists and Participants . 7 Common Core State Standards . 9 National Standards for History . 10 SECTION II: LANGUAGE . 11 Statement on Terminology . 12 SECTION III: LESSON PLANS . 14 Lesson Plans and Resources on Japanese American Incarceration . 15 Lesson Ideas for Japanese American Incarceration and Modern Parallels . 17 SECTION IV: YOUTH LEADERSHIP AND TAKING ACTION . 18 What Can You Do? . 19 SECTION V: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES . .. 21 NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 3 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT Thank you for participating in the Smithsonian’s National Youth Summit on Japanese American Incarceration. This Conversation Kit is designed to provide you with lesson activities and ideas for leading group discussions on the issues surrounding Japanese American incarceration and their relevance today. This kit also provides details on ways to participate in the Summit. The National Youth Summit is a program developed by the National Museum of American History in collaboration with Smithsonian Affiliations. This program is funded by the Smithsonian’s Youth Access Grants. Pamphlet, Division of Armed Forces History, Office of Curatorial Affairs, National Museum of American History Smithsonian Smithsonian National Museum of American History National Museum of American History Kenneth E. -

Australian Army Transport Journal

AUSTRALIAN ARMY TRANSPORT JOURNAL PAR ONERI The Official Journal of the Royal Australian Corps of Transport Collectors Edition ISSUE 46, 2014 RACT Equal to the Task Royal Australian Corps of Transport RACTHOC Cell MERCHANDISE SALES Banner Parade Print: $10 Banner Parade DVD Set: $11 Banner Parade Port: $20 Tobruk Dinner Port: $10 Banner Parade Port Set: $77 Corps Tie (100% Silk): $40 Princess Alice & Anne Glass Set: $15 Please Note: • Banner parade memorabilia is only available while stocks last so don’t miss out; • Member discounts apply to all financial members of the Corps fund; • Payment is by EFT and orders dispatched on receipt of payment; and • Packaging and postage are extra. Please email your order to [email protected] 2 | AUSTRALIAN ARMY TRANSPORT JOURNAL 2014 CORPS MATTERS TRADE MATTERS GENERAL INTEREST UNIT LINES CORPS MATTERS OPERATIONS GENERAL INTEREST UNIT LINES RACT CELEBRATING 41 YEARS RACT RACT CELEBRATING 40 YEARS Equal to the Task Royal Australian Corps of Transport Corps Conference 2014 2 - 4 April 2014 Puckapunyal Military Area Further information will be made available on the RACT Website in the New Year. Above: HQ Army School of Transport staff outside their “new” Headquarters Building 3 | AUSTRALIAN ARMY TRANSPORT JOURNAL 2014 CORPS MATTERS TRADE MATTERS GENERAL INTEREST UNIT LINES CONTENTS PAGE TITLE 67 DSCMA UPDATE 5 HOC MESSAGE 72 12 MONTHS AS A TPT MANAGER AT GOOGLE 6 DHOC MESSAGE 74 IT WAS THE BEST & WORST OF TRADES 7 CRSM MESSAGE 75 CORPS COL-IN-CHIEF, WHAT’S THE POINT? 8 REP COL COMDT MESSAGE -

The Internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II

The Internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II Instructor: Robert Finkelstein Executive Order 9066 Public Law 503 Internment Most of the Japanese–Americans were released in early 1945 My Interests and Biases Naturalization Act of 1790 Amended in 1795, and 1798 Under John Adams Repealed in 1952 -McCarran-Walter Immigration Act Alien and Sedition Acts 1798 Quasi-War with France The Sedition Act and the Alien Friends Act were allowed to expire in 1800 and 1801, respectively Enemy Aliens Act did not expire American Nativism Nation of Immigrants Irish Immigration American Party – “Know Nothing” Blaine Amendment Nordic Race 14th Amendment Post Civil War Changed the balance with State Rights United States v. Wong Kim Ark In 1898 the Supreme Court decision in granted citizenship to an American-born child of Chinese parents Not been tested with other people Chinese and Japanese Immigration Chinese were ridiculed Japanese were praised this changed over time Lived in their own communities – similar to Irish, Italians, Jews, Polish, etc. Japanese immigrants arrive in Hawaii - 1868 Japanese immigrants arrive to the mainland United States 1869 Anti-Immigration Laws Welcoming Europeans – Statue of Liberty Chinese Exclusion Act is passed, prohibiting immigration from China. It was enforced between 1882 and 1892 San Francisco School Board passes a regulation sending all Japanese children to the segregated Chinese school Russo-Japanese War Feb. 8, 1904 Sneak Attack on the Russian Fleet in Port Arthur Japan was winning the war Treaty in Portsmouth, NH – Teddy Roosevelt – Noble Peace Prize Non white race defeats white race Theodore Roosevelt Theodore Roosevelt (like Taft after him) used the influence of the White House to prevent open anti-Japanese discrimination T. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Fighting the War

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > ANCHOR > The Great Depression and World War II (1929 and 1945) > Fighting the War Fighting the War [1] Share it now! U.S. involvement in World War II lasted for nearly four years, and more Americans died than in any war except the Civil War — though even those numbers paled in comparison to the carnage other nations endured. For six months after Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces took island after island in the Pacific, and Americans feared an invasion of the West Coast of the United States. In the summer of 1942 the tide of the war in the Pacific began to turn, and for three years, Allied forces fought their way through the Pacific to the shores of Japan. In Europe, the Soviet Union desperately fought the Germans in the east, while American and British troops fought their way through North Africa, invaded Italy, and finally opened a second front in France in 1944. In this chapter you’ll follow the progress of the war from 1942 to 1945. Documentary film, radio broadcasts, contemporary magazine articles, battle maps, and oral histories will help you explore some of the war’s major events. Section Contents The United States in World War II [2] Timeline of World War II: 1942–1945 [3] The Science and Technology of World War II [4] The USS North Carolina [5] Midway [6] D-Day [7] Landing in Europe [8] Liberating France [9] The Battle of the Bulge [10] Iwo Jima [11] The Holocaust [12] User Tags: Chapter Cover [13] D-Day [14] history [15] holocaust [16] Iwo Jima [17] North Carolina History [18] -

The Attack Will Go on the 317Th Infantry Regiment in World War Ii

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II Dean James Dominique Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Dominique, Dean James, "The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 3946. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATTACK WILL GO ON THE 317TH INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts In The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Dean James Dominique B.S., Regis University, 1997 August 2003 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS........................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1