Shell Identification Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHELKS Scientific Names: Busycon Canaliculatum Busycon Carica

Colloquial Nicknames: Channeled Whelk Knobbed Whelk WHELKS Scientific names: Busycon canaliculatum Busycon carica Field Markings: The shell of open with their strong muscular foot. As both species is yellow-red or soon as the valves open, even the tiniest orange inside and pale gray amount, the whelk wedges in the sharp edge outside. of its shell, inserts the proboscis and Size: Channeled whelk grows up devours the soft body of the clam. to 8 inches long; knobbed whelk Mating occurs by way of internal grows up to 9 inches long and 4.5 inches wide fertilization; sexes are separate. The egg casing of the whelk is a Habitat: Sandy or muddy bottoms long strand of yellowish, parchment-like disks, resembling a Seasonal Appearance: Year-round necklace - its unique shape is sculpted by the whelk’s foot. Egg cases can be two to three feet long and have 70 to 100 capsules, DISTINGUISHING FEATURES AND each of which can hold 20 to 100 eggs. Newly hatched channeled BEHAVIORS whelks escape from small holes at the top of each egg case with Whelks are large snails with massive shells. The two most their shells already on. Egg cases are sometimes found along common species in Narragansett Bay are the knobbed whelk the Bay shoreline, washed up with the high tide debris. and the channeled whelk. The knobbed whelk is the largest marine snail in the Bay. It Relationship to People is pear-shaped with a flared outer lip and knobs on the shoulder Both channeled and knobbed whelks scavenge and hunt for of its shell. -

Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220)

Reprint as at 1 October 2017 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220) Paul Reeves, Governor-General Order in Council At Wellington this 2nd day of September 1986 Present: The Right Hon G W R Palmer presiding in Council Pursuant to section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1983, His Excellency the Governor-Gener- al, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. Contents Page 1 Title, commencement, and application 4 2 Interpretation 4 Part 1 Southland area Total prohibition 3 Total prohibitions 15 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this official reprint. Note 4 at the end of this reprint provides a list of the amendments incorporated. These regulations are administered by the Ministry for Primary Industries. 1 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Reprinted as at Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 1 October 2017 Certain fishing methods prohibited 3A Certain fishing methods prohibited in defined areas 16 3AB Set net fishing prohibited in defined area from Slope Point to Sand 18 Hill Point Minimum set net mesh size 3B Minimum set net mesh size 19 3BA Minimum net mesh for queen scallop trawling 20 Set net soak times 3C Set net soak times 20 3D Restrictions on fishing in paua quota management areas 21 3E Labelling of containers for paua taken in any PAU 5 quota 21 management area 3F Marking of blue cod pots and fish holding pots [Revoked] 21 Trawling 4 Trawling prohibited -

Faunistic Assemblages of a Sublittoral Coarse Sand Habitat of the Northwestern Mediterranean

Scientia Marina 75(1) March 2011, 189-196, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.2011.75n1189 Faunistic assemblages of a sublittoral coarse sand habitat of the northwestern Mediterranean EVA PUBILL 1, PERE ABELLÓ 1, MONTSERRAT RAMÓN 2,1 and MARC BAETA 3 1 Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, 08003 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centre Oceanogràfic de les Balears, Moll de Ponent s/n, 07015 Palma de Mallorca, Spain. 3 Tecnoambiente S.L., carrer Indústria, 550-552, 08918 Badalona, Spain. SUMMARY: The sublittoral megabenthic assemblages of a northwestern Mediterranean coarse sandy beach exploited for the bivalve Callista chione were studied. The spatial and bathymetric variability of its distinctive faunal assemblages was characterised by quantitative sampling performed with a clam dredge. The taxa studied were Mollusca Bivalvia and Gastropoda, Crustacea Decapoda, Echinodermata and Pisces, which accounted for over 99% of the total biomass. Three well- differentiated species assemblages were identified: (1) assemblage MSS (Medium Sand Shallow) in medium sand (D50=0.37 mm) and shallow waters (mean depth =6.5 m), (2) assemblage CSS (Coarse Sand Shallow) in coarse sand (D50=0.62 mm) in shallow waters (mean depth =6.7 m), and (3) assemblage CSD (Coarse Sand Deep) in coarse sand (D50=0.64 mm) in deeper waters (mean depth =16.2 m). Assemblage MSS was characterised by the codominance of the bivalves Mactra stultorum and Acanthocardia tuberculata. C. chione was dominant in both density and biomass in assemblages CSS and CSD. -

Ring Test Bulletin – RTB#52

www.nmbaqcs.org Ring Test Bulletin – RTB#52 Tim Worsfold David Hall Søren Pears (Images) APEM Ltd. March 2017 E-mail: [email protected] RING TEST DETAILS Ring Test #52 Type/Contents – Targeted - Bivalvia Circulated – 12/11/16 Results deadline – 16/12/16 Number of Subscribing Laboratories – 24 Number of Participating Laboratories – 21 Number of Results Received – 21* *multiple data entries per laboratory permitted Summary of differences Total differences for 21 Specimen Genus Species Size returns Genus Species RT5201 Thyasira flexuosa 2-3mm 0 1 RT5202 Abra alba 10mm 0 1 RT5203 Cochlodesma praetenue 3-5mm 5 5 RT5204 Thyasira equalis 2-4mm 3 9 RT5205 Abra nitida 4-6mm 0 1 RT5206 Fabulina fabula 3-5mm 1 1 RT5207 Cerastoderma edule 1mm 6 13 RT5208 Tellimya ferruginosa 3-4mm 0 0 RT5209 Nucula nucleus 8-9mm 0 3 RT5210 Nucula nitidosa 2-3mm 1 3 RT5211 Asbjornsenia pygmaea 2-3mm 1 1 RT5212 Abra prismatica 3-5mm 1 1 RT5213 Chamelea striatula 3-4mm 7 9 RT5214 Montacuta substriata 1-2mm 5 5 RT5215 Spisula subtruncata 1mm 4 6 RT5216 Adontorhina similis 1-2mm 4 4 RT5217 Goodallia triangularis 1-2mm 0 0 RT5218 Scrobicularia plana 1mm 20 20 RT5219 Cerastoderma edule 2-3mm 9 13 RT5220 Arctica islandica 1mm 4 4 RT5221 Kurtiella bidentata 2-3mm 2 2 RT5222 Venerupis corrugata 2-3mm 9 9 RT5223 Barnea parva 10-20mm 0 0 RT5224 Abra alba 4-5mm 1 2 RT5225 Nucula nucleus 2mm 0 11 Total differences 83 124 Average 4.0 5.9 differences /lab. NMBAQC RT#52 bulletin Differences 10 15 20 25 0 5 Arranged in order of increasing number of differences (by specific followed by generic errors). -

Marine Bivalve Molluscs

Marine Bivalve Molluscs Marine Bivalve Molluscs Second Edition Elizabeth Gosling This edition first published 2015 © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd First edition published 2003 © Fishing News Books, a division of Blackwell Publishing Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

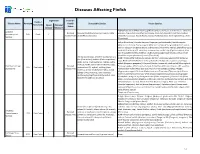

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Paleoenvironmental Interpretation of Late Glacial and Post

PALEOENVIRONMENTAL INTERPRETATION OF LATE GLACIAL AND POST- GLACIAL FOSSIL MARINE MOLLUSCS, EUREKA SOUND, CANADIAN ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Shanshan Cai © Copyright Shanshan Cai, April 2006. All rights reserved. i PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT A total of 5065 specimens (5018 valves of bivalve and 47 gastropod shells) have been identified and classified into 27 species from 55 samples collected from raised glaciomarine and estuarine sediments, and glacial tills. -

Morphological Variations of the Shell of the Bivalve Lucina Pectinata

I S S N 2 3 47-6 8 9 3 Volume 10 Number2 Journal of Advances in Biology Morphological variations of the shell of the bivalve Lucina pectinata (Gmelin, 1791) Emma MODESTIN PhD of Biogeography, zoology and Ecology University of the French Antilles, UMR AREA DEV ABSTRACT In Martinique, the species Lucina pectinata (Gmelin, 1791) is called "mud clam, white clam or mangrove clam" by bivalve fishermen depending on the harvesting environment. Indeed, the individuals collected have differences as regards the shape and colour of the shell. The hypothesis is that the shape of the shell of L. pectinata (P. pectinatus) shows significant variations from one population to another. This paper intends to verify this hypothesis by means of a simple morphometric study. The comparison of the shape of the shell of individuals from different populations was done based on samples taken at four different sites. The standard measurements (length (L), width or thickness (E - épaisseur) and height (H)) were taken and the morphometric indices (L/H; L/E; E/H) were established. These indices of shape differ significantly among the various populations. This intraspecific polymorphism of the shape of the shell of P. pectinatus could be related to the nature of the sediment (granulometry, density, hardness) and/or the predation. The shells are significantly more elongated in a loose muddy sediment than in a hard muddy sediment or one rich in clay. They are significantly more convex in brackish environments and this is probably due to the presence of more specialised predators or of more muddy sediments. Keywords Lucina pectinata, bivalve, polymorphism of shape of shell, ecology, mangrove swamp, French Antilles. -

Performance of the New England Hydraulic Dredge for the Harvest Of'stimpson~Surf Clams

PERFORMANCE OF THE NEW ENGLAND HYDRAULIC DREDGE FOR THE HARVEST OF'STIMPSON~SURF CLAMS Inv d Experimental Biology Division*. Deparhnent of Fisheries and Oceans Canada Maurice Lamontagne Instihite 850 route de la Mer f O00 Mont-Joli (~uébec) G5H 324 Canadian Industry Report of isheries and Aquatic Sciences 235 ? nadian Industry Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences canaain the ~e?iaIts:Bf ramh and develotrment iradustq fof MkF irnmedia~elar Iutuw1appdkashn. They are da.r.ected pfimarbly tmard indiziduak .h $ha primary and secondary çccrors of the fishing and marine mduaries. ?i,o ratlrMhn k phced on sulbjmt mcta and the series reflects the broad inoemrs and p~2ek5&oh Department d Fisher& and Oceans. aamely. fishiesad aqwticsc+awe~,. .' 1t@u~rr5reprts m. be cimed & full pnsblicatbns. The cornkt citatian aowars . abri the abatracr of each report. Eacb rekl is a&rrxad in Awair %ie.nr& ifid . technical publicatio . Sumber;l-9li e lndustrial Devel- opsnent BranCh. Technical Reports of th. lndiausrrkf ikxelo~mentÉranch. a& - ,Tecknical Reports of the &-sk*an's Servk Branch. kumkrs 62- I tO Giztaisseed as . Dapan~enzof Fishsies and the Em-i~onment.Fisher& and Màrine Service fndustry Reports. The current ysies name kas chmgel ~ithreport number 111. lndwsrr! reports are produc& rqiortdk bur are numkred nationrtlty. Requests .for indi\ idual rqporfs w il1 be fifkd by the issuing~rqblishmentl~tcdon the front cûvw and title page. Out-of-stwk feports-will k svpplied for fw? b'J; commacia~agents. Les rapporis 4 1'indlasrrk am t knmf k résultats des acîivitis de mher&c et de diveloppern-enl qui peuvent &se utiles a I'industrie gour des applications immédiates ou fatures. -

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum Undatum in North Wales

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Marine Environmental Protection MSc Redacted version September 2014 School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University Bangor University Bangor Gwynedd Wales LL57 2DG Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the M.Sc. in Marine Environmental Protection. The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references and a bibliography is appended. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: Date: 12/09/2014 i Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Abstract A mark-recapture study and fisheries data analysis for the common whelk, Buccinum undatum, was undertaken for catches on a commercial fishing vessel operating from The fishing location, north Wales, from June-July 2014. Laboratory experiments were conducted on B.undatum to investigate tag retention rates and behavioural responses after being exposed to a number of treatments. Thick rubber bands were found to have a 100 % tag retention rate after four months. Riddling, tagging and air exposure do not affect the behavioural responses of B.undatum. The mark-recapture study was used to estimate population size and movement. 4007 whelks were tagged with thick rubber bands over three tagging events. -

The Impact of Hydraulic Blade Dredging on a Benthic Megafaunal Community in the Clyde Sea Area, Scotland

Journal of Sea Research 50 (2003) 45–56 www.elsevier.com/locate/seares The impact of hydraulic blade dredging on a benthic megafaunal community in the Clyde Sea area, Scotland C. Hauton*, R.J.A. Atkinson, P.G. Moore University Marine Biological Station Millport (UMBSM), Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland, KA28 0EG, UK Received 4 December 2002; accepted 13 February 2003 Abstract A study was made of the impacts on a benthic megafaunal community of a hydraulic blade dredge fishing for razor clams Ensis spp. within the Clyde Sea area. Damage caused to the target species and the discard collected by the dredge as well as the fauna dislodged by the dredge but left exposed at the surface of the seabed was quantified. The dredge contents and the dislodged fauna were dominated by the burrowing heart urchin Echinocardium cordatum, approximately 60–70% of which survived the fishing process intact. The next most dominant species, the target razor clam species Ensis siliqua and E. arcuatus as well as the common otter shell Lutraria lutraria, did not survive the fishing process as well as E. cordatum, with between 20 and 100% of individuals suffering severe damage in any one dredge haul. Additional experiments were conducted to quantify the reburial capacity of dredged fauna that was returned to the seabed as discard. Approximately 85% of razor clams retained the ability to rapidly rebury into both undredged and dredged sand, as did the majority of those heart urchins Echinocardium cordatum which did not suffer aerial exposure. Individual E. cordatum which were brought to surface in the dredge collecting cage were unable to successfully rebury within three hours of being returned to the seabed. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos

A Chave Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2017 Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (2017): Nomes galegos dos moluscos recomendados pola Chave. http://www.achave.gal/wp-content/uploads/achave_osnomesgalegosdos_moluscos.pdf 1 Notas introdutorias O que contén este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas). En total, achéganse nomes galegos para 534 especies de moluscos. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica que considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos. Aquí apúntase, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos que hai en cada familia. A seguir vén o corpo do documento, onde se indica, especie por especie, alén do nome científico, os nomes galegos e ingleses de cada molusco (nalgún caso, tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles). Ao final inclúese unha listaxe de referencias bibliográficas que foron utilizadas para a elaboración do presente documento. Nalgunhas desas referencias recolléronse ou propuxéronse nomes galegos para os moluscos, quer xenéricos quer específicos. Outras referencias achegan nomes para os moluscos noutras linguas, que tamén foron tidos en conta. Alén diso, inclúense algunhas fontes básicas a respecto da metodoloxía e dos criterios terminolóxicos empregados. 2 Tratamento terminolóxico De modo moi resumido, traballouse nas seguintes liñas e cos seguintes criterios: En primeiro lugar, aprofundouse no acervo lingüístico galego. A respecto dos nomes dos moluscos, a lingua galega é riquísima e dispomos dunha chea de nomes, tanto específicos (que designan un único animal) como xenéricos (que designan varios animais parecidos).