Ambient Concentrations of Selected Organochlorines in Estuaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

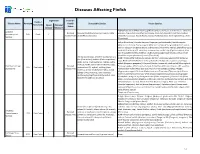

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum Undatum in North Wales

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Marine Environmental Protection MSc Redacted version September 2014 School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University Bangor University Bangor Gwynedd Wales LL57 2DG Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the M.Sc. in Marine Environmental Protection. The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references and a bibliography is appended. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: Date: 12/09/2014 i Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Abstract A mark-recapture study and fisheries data analysis for the common whelk, Buccinum undatum, was undertaken for catches on a commercial fishing vessel operating from The fishing location, north Wales, from June-July 2014. Laboratory experiments were conducted on B.undatum to investigate tag retention rates and behavioural responses after being exposed to a number of treatments. Thick rubber bands were found to have a 100 % tag retention rate after four months. Riddling, tagging and air exposure do not affect the behavioural responses of B.undatum. The mark-recapture study was used to estimate population size and movement. 4007 whelks were tagged with thick rubber bands over three tagging events. -

Shellfish Size at Maturity Review

Shellfish Size at Maturity Review Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 American hard-shelled clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Crawfish (Palinurus spp.) ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Edible/brown crab (Cancer pagurus) ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Grooved carpetshell clam (Ruditapes decussatus) ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Lobster (Homarus gammarus) ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) -

First Detection of Tetrodotoxin in Bivalves and Gastropods from the French Mainland Coasts

toxins Article First Detection of Tetrodotoxin in Bivalves and Gastropods from the French Mainland Coasts Vincent Hort 1,*, Nathalie Arnich 2, Thierry Guérin 1 , Gwenaëlle Lavison-Bompard 1 and Marina Nicolas 1 1 Université Paris-Est, ANSES, Laboratory for Food Safety, F-94701 Maisons-Alfort, France; [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (G.L.-B.); [email protected] (M.N.) 2 ANSES, Risk Assessment Directorate, F-94701 Maisons-Alfort, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-1-4977-4671 Received: 13 August 2020; Accepted: 11 September 2020; Published: 16 September 2020 Abstract: In 2015, tetrodotoxins (TTXs) were considered a potential threat in Europe since several studies had shown the presence of these toxins in European bivalve molluscs. In this study, we investigated the occurrence of TTXs in 127 bivalve samples (mussels and oysters) and in 66 gastropod samples (whelks) collected all along the French mainland coasts in 2017 and 2018. Analyses were carried out after optimization and in-house validation of a performing hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography associated with tandem mass spectrometry (HILIC-MS/MS) method. The concentration set by European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) not expected to result in adverse effects (44 µg TTX equivalent/kg) was never exceeded, but TTX was detected in three mussel samples and one whelk sample (1.7–11.2 µg/kg). The tissue distribution of TTX in this whelk sample showed higher concentrations in the digestive gland, stomach and gonads (7.4 µg TTX/kg) than in the rest of the whelk tissues (below the limit of detection of 1.7 µg TTX/kg). -

MOLLUSCS Species Names – for Consultation 1

MOLLUSCS species names – for consultation English name ‘Standard’ Gaelic name Gen Scientific name Notes Neologisms in italics der MOLLUSC moileasg m MOLLUSCS moileasgan SEASHELL slige mhara f SEASHELLS sligean mara SHELLFISH (singular) maorach m SHELLFISH (plural) maoraich UNIVALVE SHELLFISH aon-mhogalach m (singular) UNIVALVE SHELLFISH aon-mhogalaich (plural) BIVALVE SHELLFISH dà-mhogalach m (singular) BIVALVE SHELLFISH dà-mhogalaich (plural) LIMPET (general) bàirneach f LIMPETS bàirnich common limpet bàirneach chumanta f Patella vulgata ‘common limpet’ slit limpet bàirneach eagach f Emarginula fissura ‘notched limpet’ keyhole limpet bàirneach thollta f Diodora graeca ‘holed limpet’ china limpet bàirneach dhromanach f Patella ulyssiponensis ‘ridged limpet’ blue-rayed limpet copan Moire m Patella pellucida ‘The Virgin Mary’s cup’ tortoiseshell limpet bàirneach riabhach f Testudinalia ‘brindled limpet’ testudinalis white tortoiseshell bàirneach bhàn f Tectura virginea ‘fair limpet’ limpet TOP SHELL brùiteag f TOP SHELLS brùiteagan f painted top brùiteag dhotamain f Calliostoma ‘spinning top shell’ zizyphinum turban top brùiteag thurbain f Gibbula magus ‘turban top shell’ grey top brùiteag liath f Gibbula cineraria ‘grey top shell’ flat top brùiteag thollta f Gibbula umbilicalis ‘holed top shell’ pheasant shell slige easaig f Tricolia pullus ‘pheasant shell’ WINKLE (general) faochag f WINKLES faochagan f banded chink shell faochag chlaiseach bhannach f Lacuna vincta ‘banded grooved winkle’ common winkle faochag chumanta f Littorina littorea ‘common winkle’ rough winkle (group) faochag gharbh f Littorina spp. ‘rough winkle’ small winkle faochag bheag f Melarhaphe neritoides ‘small winkle’ flat winkle (2 species) faochag rèidh f Littorina mariae & L. ‘flat winkle’ 1 MOLLUSCS species names – for consultation littoralis mudsnail (group) seilcheag làthaich f Fam. -

Shelled Molluscs

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) Archimer http://www.ifremer.fr/docelec/ ©UNESCO-EOLSS Archive Institutionnelle de l’Ifremer Shelled Molluscs Berthou P.1, Poutiers J.M.2, Goulletquer P.1, Dao J.C.1 1 : Institut Français de Recherche pour l'Exploitation de la Mer, Plouzané, France 2 : Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France Abstract: Shelled molluscs are comprised of bivalves and gastropods. They are settled mainly on the continental shelf as benthic and sedentary animals due to their heavy protective shell. They can stand a wide range of environmental conditions. They are found in the whole trophic chain and are particle feeders, herbivorous, carnivorous, and predators. Exploited mollusc species are numerous. The main groups of gastropods are the whelks, conchs, abalones, tops, and turbans; and those of bivalve species are oysters, mussels, scallops, and clams. They are mainly used for food, but also for ornamental purposes, in shellcraft industries and jewelery. Consumed species are produced by fisheries and aquaculture, the latter representing 75% of the total 11.4 millions metric tons landed worldwide in 1996. Aquaculture, which mainly concerns bivalves (oysters, scallops, and mussels) relies on the simple techniques of producing juveniles, natural spat collection, and hatchery, and the fact that many species are planktivores. Keywords: bivalves, gastropods, fisheries, aquaculture, biology, fishing gears, management To cite this chapter Berthou P., Poutiers J.M., Goulletquer P., Dao J.C., SHELLED MOLLUSCS, in FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE, from Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, Oxford ,UK, [http://www.eolss.net] 1 1. -

Juvenile Mortality in Benthic Marine Invertebrates

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 146: 265-282, 1997 Published January 30 Mar Ecol Prog Ser REVIEW Juvenile mortality in benthic marine invertebrates Louis A. Gosselin*,Pei-Yuan Qian Department of Biology, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Clear Water Bay, Kowloon, Hong Kong ABSTRACT Th~rtyyears ago Thorson (1966 Neth J Sea Res 3 267-293) calculated that juvenile mor- tallty in manne bivalves could exceed 98 6% Subsequently juvenile mortality rates have been assumed to be high and to influence the evolution of life history traits However there have been no attempts to establish whether high luvenile mortality IS common or to determine if lnterspecific trends in luven~lemortality exist To address th~sIssue we revlewed 30 studies of age-specif~cmortality among bivalves, gastropods, barnacles ascid~ans,bryozoans and echinoderms High juvenile mortality is widespread among benthic marlne Invertebrates with 20 of the 30 stud~esreporting levels of luve- n~lemortal~ty >90% Mortal~tyis part~cularlyh~gh during the first moments of luvenile life and can exceed 30% during the f~rstday Pool~ngsurv~vorship data from all species revealed a general trend with survivorsh~pdecreasing exponentially during the first days or weeks of juvenile life until by the age of 4 mo, virtually all cohorts were reduced to <20% of their ~nitialnumbers ~nortalityremained low thereafter We suggest that extreme vulnerability at the onset of luvenile life is a shared tra~tthat is largely responsible for the surv~vorshiptrend Natural variation within this trend -

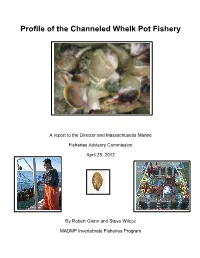

Profile of the Channeled Whelk Pot Fishery

Profile of the Channeled Whelk Pot Fishery A report to the Director and Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Advisory Commission April 25, 2012 By Robert Glenn and Steve Wilcox MADMF Invertebrate Fisheries Program Background The channeled whelk fishery in Massachusetts has traditionally been small scale, with a small number of full- time fishermen and a moderate number of part-time fishermen who fished for whelk seasonally. The majority of channeled whelks are harvested through directed effort with “conch” pots, and a smaller portion harvested as by-catch from draggers and clam dredgers operating in Nantucket Sound. From 1950 to the late 1970’s whelk landings in MA (channeled and knobbed) were less than 250,000 lbs annually (source NMFS). In the 1980’s whelk landings increased substantially, exceeding 1,000,000 lbs for the first time, presumably from an increase in market demand. It was first possible to differentiate between channeled whelk and knobbed whelk landings in the early 1990’s with improvements to the landings data reporting system. Channeled whelk landings varied roughly between 1.5 and 2 million pounds from the 1990’s through the early 2000’s (Figure 1). Some of the variation in the landings during this time period is likely explained by fluctuations in lobster landings and effort (Figure 1). Many lobstermen fish for channeled whelk seasonally to supplement their income. When lobster were abundant and landings were high there appears to be a drop in channeled whelk landings. Conversely, when lobster abundance and landings declined, channeled whelk landings and effort increased. This is especially apparent after 2002 when the lobster population in Southern New England started to collapse. -

Marine Invasive Species in Nordic Waters - Fact Sheet

NOBANIS - Marine invasive species in Nordic waters - Fact Sheet Rapana venosa Author of this species fact sheet: Kathe R. Jensen, Zoological Museum, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 København Ø, Denmark. Phone: +45 353-21083, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Jensen, Kathe R. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Rapana venosa – From: Identification key to marine invasive species in Nordic waters – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Species name Rapana venosa, (Valenciennes, 1846) – Veined rapa whelk Synonyms Purpura venosa Valenciennes, 1846; Rapana thomasiana Crosse, 1861; ?Rapana marginata (Valenciennes, 1846); ?Rapana pechiliensis Grabau & King, 1928; Rapana pontica Nordsieck, 1969. Common names Veined rapa whelk, Asian rapa whelk (USA, UK); Thomas’ whelk (English common name for Black Sea whelks identified as R. thomasiana); Cocozza, Bobolone (IT); Geaderde stekelhoorn (NL); Bai top shell (commercial name for Bulgarian Black Sea specimens); Akanishi (JP). Taxonomic note The genus Rapana is sometimes referred to the family Muricidae (e.g., DAISIE, 2006), sometimes to Thaididae (e.g., Koutsoubas & Voultsiadou-Koukoura, 1991; Mann & Harding, 2000). According to World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) the family should be Muricidae, and the Thaididae is considered a synonym of Rapaninae, a subfamily of Muricidae (see Bouchet & Rocroi, 2005). Identification Rapana venosa is a large, 9-16 cm shell length, species with a heavy, strongly sculptured shell. Specimens up to 17.5 cm have been recorded in the Black Sea (Micu et al., 2008). The spire is relatively short, less than half the height of the aperture. -

The Abundance, Movement and Site Fidelity of the Adult Whelk, Buccinum Undatum, in the Territorial Waters of the Isle of Man

The abundance, movement and site fidelity of the adult whelk, Buccinum undatum, in the territorial waters of the Isle of Man A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Marine Environmental Protection Bangor University 2015 Matthew Robinson BSc Marine Biology (2010, University of Liverpool) School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Menai Bridge, Anglesey, LL59 5EY, UK www.bangor.ac.uk [email protected] Submitted in September, 2015 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. Candidate: Date: 18/09/2015 This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the MSc in Marine Environmental Protection. Candidate: Date: 18/09/2015 The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Candidate: Date: 18/09/2015 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Candidate: Date: 18/09/2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Michel Kaiser, Dr Isobel Bloor and Sam Dignan for their support and guidance during the project. I am immensely grateful to Jon Jo Skillen, skipper of ‘Boy Shayne’, and Jordan Corkill for their efforts and enthusiasm for making the project a success. Thank you also to Lucy May for her help during the tag making and tagging phase of the project, and for her support throughout. The abundance, movement and site fidelity of the adult whelk, Buccinum undatum, in the territorial waters of the Isle of Man Abstract The maximum and daily movements of the common whelk (Buccinum undatum) were investigated in Ramsey Bay, northeast Isle of Man from June to July 2015. -

The Molluscan Fisheries of Germany* P

The Molluscan Fisheries of Germany* p MATIHIASN. L SEAMAN FisheriesBiology Department Institute for MarineResearch 24105 Kiel, Germany MAARTENRUTH FisheriesAgency State of Schleswig-Holstein 24148 Kiel, Germany ABSTRACT The German molluscan fishery has always concentrated on the North Sea. Mollusks occur in the Baltic Sea, but are not as marketable. In prehistory and the Middle Ages, coastal inhabitants gathered mussels, Mytilus edulis, cockles, Cerastoderma edule, and flat oysters, Ostrea edulis, for food and also used mussels as agricultural fertilizer. An organized oyster fisherydeveloped in the 16th century and had considerable economic importance for 300 years. Oysters were dredged with sailing vessels near the coast, as well as far offshore. Catches peaked in the second half of the l 9th century at 3-5 million oysters per year. They declined dramatically in the following decades due to permanent recruitment failures, and the flat oyster finally disappeared from the German coast in the l 950's. An organized fishery for freshwater pearl mussels, Margaritifera margaritifera, also developed at the end of the Middle Ages, but mismanagement and environmental degradation since the late 19th century have brought this species to the brink of extinction as well. Other mollusks harvested on a smaller scale in the past have been softshell clams, Mya arenaria, and whelks, Buccinum undatum. The modern mussel fishery for human food began in 1929 with the introduction of novel dredging methods. Annual catches were in the order of a few thousand tons during the first half of this century and have attained 20,000-60,000 tons since the early l 980's; concomitantly, prices have increased five-fold in recent decades. -

Shell Whelk Dog Whelk Turret It Could Be a Periwinkle Shell (Nucella Lapillus) Shell Spire Shell Thick Top Shell (Osilinus Lineatus) Dark Stripes Key on Body

It could be a type of It could be a type of It could be a It could be a type of topshell whelk Dog whelk turret It could be a periwinkle Shell (Nucella lapillus) shell spire shell Thick top shell (Osilinus lineatus) Dark stripes Key on body Egg Underside capsules Actual size It could be a type of (Hydrobia sp) Common periwinkle spiral worm White ‘Colar’ (Littorina littorea) Flat periwinkle (Littorinasp) Yes Roughly ‘ribbed’ shell. Very high up shore ‘Tooth inside (Turitella communis) opening (Spirorbis sp) Does it have 6 Common whelk No (Buccinum undatum) Yes or more whorls Brown, speckled Netted dog whelk body (twists)? Painted topshell (Nassarius reticulatus) (Calliostoma zizyphinum) No Rough periwinkle Flattened spire Yes Is it long, thin (Littorina saxatilis) Yes Yes and cone shaped Is it permanently No like a unicorn’s horn? attached to Is there a groove or teeth No Is there mother No a surface? in the shell opening? of pearl inside It could be a type of the shell opening? bivalve Yes Yes Common otter-shell (Lutraria lutraria) Bean-like tellin No Is the shell in (Fabulina fabula) Is it 2 parts? spiraled? Common cockle (Cerastoderma edule) It could be a Flat, rounded No sand No Great scallop mason It could be a Is the shell a (Pecten maximus) shell Razor shell worm keel worm Wedge-shaped Is the case dome or (Ensis sp) No Pacific oyster shell made from Yes cone shape? (Crassostrea gigas) Shell can be Peppery furrow shell very large (Scrobicularia plana) sand grains? Elongated and and doesn’t (Lanice conchilega) deep-bodied fully close with large ‘frills’ No (Pomatoceros sp) Yes It could be a type of sea urchin It could be a type of An acorn Native oyster Empty barnacle barnacle Does it have that may be found in estuaries and shores in the UK.