Marine Invasive Species in Nordic Waters - Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Severe Introduced Predator Impacts Despite Attempted Functional Eradication

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.451788; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Severe introduced predator impacts despite attempted functional eradication 2 Brian S. Cheng1,2, Jeffrey Blumenthal3,4, Andrew L. Chang3,4, Jordanna Barley1, Matthew C. Ferner4,5, Karina J. Nielsen4, Gregory M. Ruiz2, Chela J. Zabin3,4 4 1Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA 01002 6 2Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Edgewater, MD, 21037 3Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Tiburon, CA 94920 8 4Estuary & Ocean Science Center, San Francisco State University, Tiburon, CA 94920 5San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, Tiburon, CA 94920 10 ORCID: BSC 0000-0003-1679-8398, ALC 0000-0002-7870-285X, MCF 0000-0002-4862-9663, KJN 0000-0002-7438-0240, JGB 0000-0002-8736-7950, CJZ 0000-0002-2636-0827 12 DECLARATIONS 14 Funding: Advancing Nature-Based Adaptation Solutions in Marin County, California State Coastal Conservancy and Marin Community Foundation. 16 Conflicts/Competing interests: The authors declare no conflicts or competing interests. Availability of data and code: All data and code has been deposited online at 18 https://github.com/brianscheng/CBOR Ethics approval: not applicable 20 Consent to participate: not applicable Consent for publication: not applicable 22 Page 1 of 37 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.451788; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

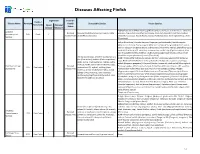

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Analysis of Synonymous Codon Usage Patterns in Sixty-Four Different Bivalve Species

Analysis of synonymous codon usage patterns in sixty-four diVerent bivalve species Marco Gerdol1, Gianluca De Moro1, Paola Venier2 and Alberto Pallavicini1 1 Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy 2 Department of Biology, University of Padova, Padova, Italy ABSTRACT Synonymous codon usage bias (CUB) is a defined as the non-random usage of codons encoding the same amino acid across diVerent genomes. This phenomenon is common to all organisms and the real weight of the many factors involved in its shaping still remains to be fully determined. So far, relatively little attention has been put in the analysis of CUB in bivalve mollusks due to the limited genomic data available. Taking advantage of the massive sequence data generated from next generation sequencing projects, we explored codon preferences in 64 diVerent species pertaining to the six major evolutionary lineages in Bivalvia. We detected remarkable diVerences across species, which are only partially dependent on phylogeny. While the intensity of CUB is mild in most organisms, a heterogeneous group of species (including Arcida and Mytilida, among the others) display higher bias and a strong preference for AT-ending codons. We show that the relative strength and direction of mutational bias, selection for translational eYciency and for translational accuracy contribute to the establishment of synonymous codon usage in bivalves. Although many aspects underlying bivalve CUB still remain obscure, we provide for the first time an overview of this phenomenon -

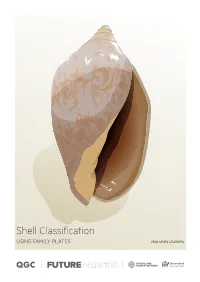

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

Biological Parameters and Feeding Behaviour of Invasive Whelk Rapana Venosa Valenciennes, 1846 in the South-Eastern Black Sea of Turkey

Journal of Coastal Life Medicine 2014; 2(6): 442-446 442 Journal of Coastal Life Medicine journal homepage: www.jclmm.com Document heading doi:10.12980/JCLM.2.2014J36 2014 by the Journal of Coastal Life Medicine. All rights reserved. 襃 Biological parameters and feeding behaviour of invasive whelk Rapana venosa Valenciennes, 1846 in the south-eastern Black Sea of Turkey Hacer Saglam*, Ertug Düzgünes Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Marine Science, Çamburnu 61530, Trabzon, Turkey PEER REVIEW ABSTRACT Peer reviewer Objective: To determine length-weight relationships, growth type and feeding behavior of the Diego Giberto, PhD in Biology, Methods:benthic predator Rapa whelk at the coast of Camburnu, south-eastern Black Sea. Researcher of the National Council Rapa whelk was monthly collected by dredge sampling on the south-eastern Black Sea of Scientific Research, Mar del Plata, at 20 m depth. The relationships between morphometric parameters of Rapa whelk were described A T rgentina. by linear and exponential models. he allomebt ric growth of each variable relative to shell length +54 223 4862586 ( ) Tel: SL was calculated fromt the function Y=aSL or logY=loga+blogSL. The functional regression b E-mail: [email protected] values were tested by -test at the 0.05 significance level if it was significantly different from Comments isometric growth. The total time spent on feeding either on mussel tissue or live mussels was rResults:ecorded for each individual under controlled conditions in laboratory. The paper is of broad interest for The length-weight relationships showed positive allometric growth and no inter-sex scientists working in invasive species variability. -

Down Effects of a Native Crab on a System of Native and Introduced Prey Emilyw

OPENQ ACCESS Freely available online e pLOSl- Preference Alters Consumptive Effects of Predators: Top- Down Effects of a Native Crab on a System of Native and Introduced Prey EmilyW. Grason"'', BenjaminG. Miner"' 1 WesternWashington University, Biology Department, Bellingham, Washington, United States of America,zshannon Point MarineCenter, Anacortes, Washington, UnitedStates of America Abstract Top-down effects of predators in systems depend on the rate at which predators consume prey, and on predator preferences among available prey. In invaded communities, these parameters might be difficult to predict because ecological relationships are typically evolutionarily novel. We examined feeding rates and preferences of a crab native to the Pacific Northwest, Cancer productus, among four prey items: two invasive species of oyster drill the marine whelks Urosaipinx cinerea and Ocenebra inornata! and two species of oyster Crassostrea gigas and Ostrea iurida! that are also consumed by U. cinerea and O. inornata. This system is also characterized by intraguild predation because crabs are predators of drills and compete with them for prey oysters!. When only the oysters were offered, crabs did not express a preferenceand consumedapproximately 9 juvenileoysters crab " day ". Wethen testedwhether crabs preferred adult drills of either U. cinerea or O. inornata, or juvenile oysters C. gigas!. While crabs consumed drills and oysters at approximately the same rate when only one type of prey was offered, they expressed a strong preference for juvenile oysters over drills when they were allowed to choose among the three prey items. This preference for oysters might negate the positive indirect effects that crabs have on oysters by crabs consuming drills trophic cascade! because crabs have a large negative direct effect on oysters when crabs, oysters, and drills co-occur. -

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum Undatum in North Wales

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Marine Environmental Protection MSc Redacted version September 2014 School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University Bangor University Bangor Gwynedd Wales LL57 2DG Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the M.Sc. in Marine Environmental Protection. The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references and a bibliography is appended. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: Date: 12/09/2014 i Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Abstract A mark-recapture study and fisheries data analysis for the common whelk, Buccinum undatum, was undertaken for catches on a commercial fishing vessel operating from The fishing location, north Wales, from June-July 2014. Laboratory experiments were conducted on B.undatum to investigate tag retention rates and behavioural responses after being exposed to a number of treatments. Thick rubber bands were found to have a 100 % tag retention rate after four months. Riddling, tagging and air exposure do not affect the behavioural responses of B.undatum. The mark-recapture study was used to estimate population size and movement. 4007 whelks were tagged with thick rubber bands over three tagging events. -

Diversity of Malacofauna from the Paleru and Moosy Backwaters Of

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2017; 5(4): 881-887 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 JEZS 2017; 5(4): 881-887 Diversity of Malacofauna from the Paleru and © 2017 JEZS Moosy backwaters of Prakasam district, Received: 22-05-2017 Accepted: 23-06-2017 Andhra Pradesh, India Darwin Ch. Department of Zoology and Aquaculture, Acharya Darwin Ch. and P Padmavathi Nagarjuna University Nagarjuna Nagar, Abstract Andhra Pradesh, India Among the various groups represented in the macrobenthic fauna of the Bay of Bengal at Prakasam P Padmavathi district, Andhra Pradesh, India, molluscs were the dominant group. Molluscs were exploited for Department of Zoology and industrial, edible and ornamental purposes and their extensive use has been reported way back from time Aquaculture, Acharya immemorial. Hence the present study was focused to investigate the diversity of Molluscan fauna along Nagarjuna University the Paleru and Moosy backwaters of Prakasam district during 2016-17 as these backwaters are not so far Nagarjuna Nagar, explored for malacofauna. A total of 23 species of molluscs (16 species of gastropods belonging to 12 Andhra Pradesh, India families and 7 species of bivalves representing 5 families) have been reported in the present study. Among these, gastropods such as Umbonium vestiarium, Telescopium telescopium and Pirenella cingulata, and bivalves like Crassostrea madrasensis and Meretrix meretrix are found to be the most dominant species in these backwaters. Keywords: Malacofauna, diversity, gastropods, bivalves, backwaters 1. Introduction Molluscans are the second largest phylum next to Arthropoda with estimates of 80,000- 100,000 described species [1]. These animals are soft bodied and are extremely diversified in shape and colour. -

Biodiversity, Habitats, Flora and Fauna

1 North East inshore Biodiversity, Habitats, Flora and Fauna - Protected Sites and Species 2 North East offshore 3 East Inshore Baseline/issues: North West Plan Areas 10 11 Baseline/issues: North East Plan Areas 1 2 4 East Offshore (Please note that the figures in brackets refer to the SA scoping database. This is • SACs: There are two SACs in the plan area – the Berwickshire and North available on the MMO website) Northumberland Coast SAC, and the Flamborough Head SAC (Biodiv_334) 5 South East inshore • Special Areas of Conservation (SACs): There are five SACs in the plan area • The Southern North Sea pSAC for harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) 6 South inshore – Solway Firth SAC, Drigg Coast SAC, Morecambe Bay SAC, Shell Flat and is currently undergoing public consultation (until 3 May 2016). Part of Lune Deep SAC and Dee Estuary SAC (Biodiv_372). The Sefton Coast the pSAC is in the offshore plan area. The pSAC stretches across the 7 South offshore SAC is a terrestrial site, mainly for designated for dune features. Although North East offshore, East inshore and offshore and South East plan areas not within the inshore marine plan area, the development of the marine plan (Biodiv_595) 8 South West inshore could affect the SAC (Biodiv_665) • SPAs: There are six SPAs in the plan area - Teesmouth and Cleveland 9 South west offshore • Special protection Areas (SPAs): There are eight SPAs in the plan area - Coast SPA, Coquet Island SPA, Lindisfarne SPA, St Abbs Head to Fast Dee Estuary SPA, Liverpool Bay SPA, Mersey Estuary SPA, Ribble and Castle SPA and the Farne Islands SPA, Flamborough Head and Bempton 10 North West inshore Alt Estuaries SPA, Mersey Narrows and North Wirral Foreshore SPA, Cliffs SPA (Biodiv_335) Morecambe Bay SPA, Duddon Estuary SPA and Upper Solway Flats and • The Northumberland Marine pSPA is currently undergoing public 11 North West offshore Marshes SPA (Biodiv_371) consultation (until 21 April 2016). -

Ambient Concentrations of Selected Organochlorines in Estuaries

Ambient concentrations of selected organochlorines in estuaries Organochlorines Programme Ministry for the Environment June 1999 Authors Sue Scobie Simon J Buckland Howard K Ellis Ray T Salter Organochlorines in New Zealand: Ambient concentrations of selected organochlorines in estuaries Published by Ministry for the Environment PO Box 10-362 Wellington ISBN 0 478 09036 6 First published November 1998 Revised June 1999 Printed on elemental chlorine free 50% recycled paper Foreword People around the world are concerned about organochlorine contaminants in the environment. Research has established that even the most remote regions of the world are affected by these persistent chemicals. Organochlorines, as gases or attached to dust, are transported vast distances by air and ocean currents – they have been found even in polar regions. Organochlorines are stored in body fat and accumulate through the food chain. Even a low concentration of emission to the environment can contribute in the long term to significant risks to the health of animals, including birds, marine mammals and humans. The contaminants of concern include dioxins (by-products of combustion and of some industrial processes), PCBs, and a number of chlorinated pesticides (for example, DDT and dieldrin). These chemicals have not been used in New Zealand for many years. But a number of industrial sites are contaminated, and dioxins continue to be released in small but significant quantities. In view of the international concern, the Government decided that we needed better information on the New Zealand situation. The Ministry for the Environment was asked to establish an Organochlorines Programme to carry out research, assess the data, and to consider management issues such as clean up targets and emission control standards. -

Rapana Venosa Potential in the GULF of MAINE Veined Rapa Whelk, Asian Rapa Whelk Invader

GUIDE TO MARINE INVADERS Rapana venosa Potential IN THE GULF OF MAINE veined rapa whelk, Asian rapa whelk Invader PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION • Rounded, heavily ribbed shell with a short spire and large body whorl • Can grow up to 7 in (18 cm) in length and is nearly as wide as it is long • Pronounced knobs leading to the spire • Gray to reddish-brown (often covered in mud in the field) with distinctive black veins throughout the shell • Distinctive deep orange color on the spire columella and aperture knobs orange Rapana venosa color HABITAT PREFERENCE body whorl • Young occupy hard substrate until reaching shell lengths greater than 2.7 in (7 cm) black veins • Adults migrate to sand and mud throughout © 2001. Juliana M. Harding where they burrow and forage on bivalves shell (e.g. clams, oysters) • Tolerates low salinities, water pollution, and oxygen deficient waters broad, flat columella Rob Gough 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 GUIDE TO MARINE INVADERS Rapana venosa Potential IN THE GULF OF MAINE veined rapa whelk, Asian rapa whelk Invader INVASION STATUS & ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS Not yet recorded in New England, this species is native to marine and estuarine waters of the western Pacific (Sea of Japan, Yellow Sea, East China Sea). It was introduced to the Black Sea (1940s), the coastlines of Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey (1959 to 1972), and Brittany (1997). The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) Trawl Survey Group collected the first specimen in the United States in 1998 at Hampton Roads, Virginia. Since then, over 18,000 specimens as well as egg cases (resembling small mats of yellow shag carpet) have been collected in the lower Chesapeake Bay. -

Growth and Development of Veined Rapa Whelk Rapana Venosa Veligers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by College of William & Mary: W&M Publish W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles 2006 Growth And Development Of Veined Rapa Whelk Rapana Venosa Veligers JM Harding Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harding, JM, "Growth And Development Of Veined Rapa Whelk Rapana Venosa Veligers" (2006). VIMS Articles. 447. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/447 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 25, No. 3, 941–946, 2006. GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF VEINED RAPA WHELK RAPANA VENOSA VELIGERS JULIANA M. HARDING Department of Fisheries Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, P. O. Box 1346, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 ABSTRACT Planktonic larvae of benthic fauna that can grow quickly in the plankton and reduce their larval period duration lessen their exposure to pelagic predators and reduce the potential for advection away from suitable habitats. Veined rapa whelks (Rapana venosa, Muricidae) lay egg masses that release planktonic veliger larvae from May through August in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Two groups of veliger larvae hatched from egg masses during June and August 2000 were cultured in the laboratory. Egg mass incubation time (time from deposition to hatch) ranged from 18–26 d at water temperatures between 22°C and 27°C.