The Molluscan Fisheries of Germany* P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

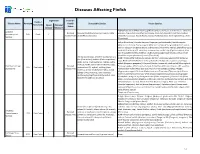

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

An Integrated Marine Data Collection for the German Bight

Discussions https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2021-45 Earth System Preprint. Discussion started: 16 February 2021 Science c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Open Access Open Data An Integrated Marine Data Collection for the German Bight – Part II: Tides, Salinity and Waves (1996 – 2015 CE) Robert Hagen1, Andreas Plüß1, Romina Ihde1, Janina Freund1, Norman Dreier2, Edgar Nehlsen2, Nico Schrage³, Peter Fröhle2, Frank Kösters1 5 1Federal Waterways Engineering and Research Institute, Hamburg, 22559, Germany 2Hamburg University of Technology, Hamburg, 21073, Germany ³Bjoernsen Consulting Engineers, Koblenz, 56070, Germany Correspondence to Robert Hagen ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0002-8446-2004) 10 Abstract The German Bight within the central North Sea is of vital importance to many industrial nations in the European Union (EU), which have obligated themselves to ensure the development of green energy facilities and technology, while improving natural habitats and still being economically competitive. These ambitious goals require a tremendous amount of careful planning and considerations, which depends heavily on data availability. For this reason, we established in close cooperation with 15 stakeholders an open-access integrated, marine data collection from 1996 to 2015 for bathymetry, surface sediments, tidal dynamics, salinity, and waves in the German Bight for science, economy, and governmental interest. This second part of a two-part publication presents data products from numerical hindcast simulations for sea surface elevation, current velocity, bottom shear stress, salinity, wave parameters and wave spectra. As an important improvement to existing data collections our model represents the variability of the bathymetry by using annually updated model topographies. -

Commercial Performance of Blue Mussel (Mytilus Edulis, L.) Stocks at a Microgeographic Scale

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Commercial Performance of Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis, L.) Stocks at a Microgeographic Scale Efflam Guillou 1, Carole Cyr 2, Jean-François Laplante 2, François Bourque 3, Nicolas Toupoint 1,2,* and Réjean Tremblay 1 1 Institut des Sciences de la Mer de Rimouski (ISMER), Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR), 310 Allée des Ursulines, CP 3300, Rimouski, QC G5L 3A1, Canada; Effl[email protected] (E.G.); [email protected] (R.T.) 2 MERINOV, Centre d’Innovation de l’aquaculture et des pêches du Québec, Secteur Aquaculture, 107-125 Chemin du Parc, Cap-aux-Meules, QC G4T 1B3, Canada; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (J.-F.L.) 3 Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Québec (MAPAQ - Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec), Fisheries and commercial aquaculture branch, 101-125, Chemin du Parc, Cap-aux-Meules, QC G4T 1B3, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(418)-986-4795 (#3227) Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 23 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Bivalve aquaculture is an important component of the economy in eastern Canada. Because of current social, environmental, economic, and resource constraints, offshore mussel cultivation seems to be a promising strategy. With the objective of optimizing farming strategies that support the sustainability and development of the mussel industry at a microgeographic scale, we evaluated, after a traditional two year production cycle, the commercial performance of spat from several mussel (Mytilus edulis) stocks originating from sites separated by less than 65 km and cultivated at two different grow-out sites (shallow lagoon and offshore waters). -

Morsum 1.4.Pub

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse an der Ferienwohnung Sylter Rabe! ANREISE NACH SYLT Die Ferienwohnung Sylter Rabe liegt im Ort Morsum auf der Insel Sylt. Sylt ist die wohl bekannteste deutsche Ferieninsel und in der Nordsee gelegen. Für die Anreise stehen die Bahn (Personen– und Autozug), die Fähren, oder das Flugzeug zur Verfügung. Das dabei am häufigsten genutzte Verkehrsmittel, ist zweifelsfrei die Bahn (Autozug für PKW Hin- und Rückfahrt ab Niebüll derzeit 92,00€ / stand Frühjahr 2016). Der größte Andrang am Autozug (Verladung erfolgt im Ort Niebüll) ist samstags, da der Samstag der klassische Wechseltag auf der Insel im Bereich der Ferienunterkünfte ist. Das bedeutet, dass die meisten Mieter bis 10.00 Uhr Ihre Unterkünfte räumen müssen und sich je Autozug nach Westerland nach Wetterlage aufmachen, die Insel zu verlas- sen. Bei schlechtem Wetter wollen alle gleich weg, bei gutem Wetter verbringt man den Tag noch auf der Insel. Diese Umstände gilt es zu berücksichti- gen, wenn man Wartezeiten am Zug vermeiden möchte. Auch wenn sich die Bahn auf Spitzenzei- ten in Verbindung mit Ferien- und Feiertagen einstellt, kann es durchaus vorkommen, dass man nicht mehr auf den geplanten Zug kommt, da be- reits einige andere Fahrzeuge in den vielen War- tespuren stehen. Dann kommt es zu Wartezeiten von 30 Min. oder länger — die Abfahrt- zeiten können online unter www.sylt-shuttle.de ebenso abgefragt werden, wie die aktuelle Lage an der Autoverladung. Seit 2016 fährt auch die RDC Deutschland einige Zeiten. Bei der Anreise können Sie an einem der vielen DRIVE-IN Schaltern in Niebüll u.a. be- quem mit EC Karte zahlen und das Rückfahrtticket gleich mitbuchen. -

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum Undatum in North Wales

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Marine Environmental Protection MSc Redacted version September 2014 School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University Bangor University Bangor Gwynedd Wales LL57 2DG Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the M.Sc. in Marine Environmental Protection. The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references and a bibliography is appended. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: Date: 12/09/2014 i Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Abstract A mark-recapture study and fisheries data analysis for the common whelk, Buccinum undatum, was undertaken for catches on a commercial fishing vessel operating from The fishing location, north Wales, from June-July 2014. Laboratory experiments were conducted on B.undatum to investigate tag retention rates and behavioural responses after being exposed to a number of treatments. Thick rubber bands were found to have a 100 % tag retention rate after four months. Riddling, tagging and air exposure do not affect the behavioural responses of B.undatum. The mark-recapture study was used to estimate population size and movement. 4007 whelks were tagged with thick rubber bands over three tagging events. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos

A Chave Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2017 Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (2017): Nomes galegos dos moluscos recomendados pola Chave. http://www.achave.gal/wp-content/uploads/achave_osnomesgalegosdos_moluscos.pdf 1 Notas introdutorias O que contén este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas). En total, achéganse nomes galegos para 534 especies de moluscos. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica que considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos. Aquí apúntase, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos que hai en cada familia. A seguir vén o corpo do documento, onde se indica, especie por especie, alén do nome científico, os nomes galegos e ingleses de cada molusco (nalgún caso, tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles). Ao final inclúese unha listaxe de referencias bibliográficas que foron utilizadas para a elaboración do presente documento. Nalgunhas desas referencias recolléronse ou propuxéronse nomes galegos para os moluscos, quer xenéricos quer específicos. Outras referencias achegan nomes para os moluscos noutras linguas, que tamén foron tidos en conta. Alén diso, inclúense algunhas fontes básicas a respecto da metodoloxía e dos criterios terminolóxicos empregados. 2 Tratamento terminolóxico De modo moi resumido, traballouse nas seguintes liñas e cos seguintes criterios: En primeiro lugar, aprofundouse no acervo lingüístico galego. A respecto dos nomes dos moluscos, a lingua galega é riquísima e dispomos dunha chea de nomes, tanto específicos (que designan un único animal) como xenéricos (que designan varios animais parecidos). -

Ambient Concentrations of Selected Organochlorines in Estuaries

Ambient concentrations of selected organochlorines in estuaries Organochlorines Programme Ministry for the Environment June 1999 Authors Sue Scobie Simon J Buckland Howard K Ellis Ray T Salter Organochlorines in New Zealand: Ambient concentrations of selected organochlorines in estuaries Published by Ministry for the Environment PO Box 10-362 Wellington ISBN 0 478 09036 6 First published November 1998 Revised June 1999 Printed on elemental chlorine free 50% recycled paper Foreword People around the world are concerned about organochlorine contaminants in the environment. Research has established that even the most remote regions of the world are affected by these persistent chemicals. Organochlorines, as gases or attached to dust, are transported vast distances by air and ocean currents – they have been found even in polar regions. Organochlorines are stored in body fat and accumulate through the food chain. Even a low concentration of emission to the environment can contribute in the long term to significant risks to the health of animals, including birds, marine mammals and humans. The contaminants of concern include dioxins (by-products of combustion and of some industrial processes), PCBs, and a number of chlorinated pesticides (for example, DDT and dieldrin). These chemicals have not been used in New Zealand for many years. But a number of industrial sites are contaminated, and dioxins continue to be released in small but significant quantities. In view of the international concern, the Government decided that we needed better information on the New Zealand situation. The Ministry for the Environment was asked to establish an Organochlorines Programme to carry out research, assess the data, and to consider management issues such as clean up targets and emission control standards. -

ADVENTURE GUIDE Getting Away from It All on Sylt

ADVENTURE GUIDE Getting away from it all on Sylt. Sylt Shuttle: the fast and relaxed way to travel. You can rely on our decades of experience. We offer the highest capacity and guarantee to get you on the move with our double-decker car trains. Running 14,000 trains a year, we are there for you from early morning to late evening: your fast, safe and reliable shuttle service. We look forward to welcoming you aboard. More information at bahn.de/syltshuttle 14,000 trains a year. The Sylt Shuttle. www.sylt.de Last update November 2019 Anz_Sylt_Buerostuhl_engl_105x210_mm_apu.indd 1 01.02.18 08:57 ADVENTURE GUIDE 3 SYLT Welcome to Sylt Boredom on Sylt? Wrong! Whether as a researcher in Denghoog or as a dis- coverer in the mudflats, whether relaxed on the massage bench or rapt on a surfboard, whether as a daydreamer sitting in a roofed wicker beach chair or as a night owl in a beach club – Sylt offers an exciting and simultaneously laid-back mixture of laissez-faire and savoir-vivre. Get started and explore Sylt. Enjoy the oases of silence and discover how many sensual pleasures the island has in store for you. No matter how you would like to spend your free time on Sylt – you will find suitable suggestions and contact data in this adventure guide. Content NATURE . 04 CULTURE AND HISTORY . 08 GUIDED TOURS AND SIGHTSEEING TOURS . 12 EXCURSIONS . 14 WELLNESS FOR YOUR SOUL . 15 WELLNESS AND HEALTH . 16 LEISURE . 18 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS . .26 SERVICE . 28 SYLT ETIQUETTE GUIDE . 32 MORE ABOUT SYLT . -

Lesson (PDF 76

Common Life in the Marine Biome Instructions: Scientists use dichotomous keys to organize and identify specimens. Dichotomous means dividing into two parts – a dichotomous key provides two choices in each step. For example: to divide a package of multi-coloured pens into two groups, you might decide to divide the pens by “has blue ink” and “does not have blue ink”. Work together at each station and use the available tools and key information to identify the different specimens. Record your answers on your results page. Station 1 – Echinoderms 1. a. Specimen has arms…………………………………………………………………….………..go to 2 b. Specimen does not have arms………………………………………………..………….go to 4 2. a. Specimen usually has 5 arms………………………..……………………………..…...go to 3 b. Specimen usually has more than 5 arms (when intact)………………………………………………………………………………………Common sun star 3. a. Specimen has a central, armoured disc with long, thin arms…………………………………………………………………………………………...Daisy brittle star b. Specimen does not armoured disc, and has large, thicker arms………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Sea star There are different species of sea star in Nova Scotian waters. Often, the easiest identification relates to colour. For example, the northern sea star and Forbes’ sea star can both have colorful bodies (purple, tan, red, etc.), however the northern sea star has a pale yellow madreporite and the Forbes’ sea star has a bright orange madreporite. 4. a. Specimen is round and flat with short, fuzz-like spines (live) or smooth without spines (dead)…..………………………………………………………………....Sand dollar b. Specimen has a dome shape with long, thicker spines (live) or lacks spines (dead).…………………………………………………………………………..Green sea urchin Common Life in the Marine Biome Page 2 of 4 Station 2 – Gastropods 1. -

Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat - September 2003 Update

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF FISHING IMPACTS ON HABITAT - SEPTEMBER 2003 UPDATE Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission SEPTEMBER 2003 GSMFC No.: 115 Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat - September 2003 Update Edited by Jeffrey K. Rester Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission September 2003 Introduction This is the third in a series of updates to the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat originally produced in February 2000. The Commission’s Habitat Subcommittee felt that the gathering of pertinent literature should continue. The third update contains 52 new articles since the publication of the last update. The update uses the same criteria that the original bibliography and first and second updates used to compile articles. It attempts to compile a listing of papers and reports that address the many effects and impacts that fishing can have on habitat and the marine environment. The bibliography is not limited to scientific literature only. It includes technical reports, state and federal agency reports, college theses, conference and meeting proceedings, popular articles, and other forms of nonscientific literature. This was done in an attempt to gather as much information on fishing impacts as possible. Researchers will be able to decide for themselves whether they feel the included information is valuable. Fishing, both recreational and commercial, can have many varying impacts on habitat and the marine environment. Whether a fisher prop scars seagrass, drops an anchor on a coral reef, or drags a trawl across the bottom, each act can alter habitat and affect fish populations. -

Shellfish Regulations

Town of Nantucket Shellfishing Policy and Regulations As Adopted on March 4, 2015 by Nantucket Board of Selectmen Amended March 23, 2016; Amended April 20, 2016 Under Authority of Massachusetts General Law, Chapter 130 Under Authority of Chapter 122 of the Code of the Town of Nantucket TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 – Shellfishing Policy for the Town of Nantucket/Purpose of Regulations Section 2 – General Regulations (Applying to Recreational, Commercial and Aquaculture Licenses) 2.1 - License or Permit Required 2.2 - Areas Where Recreational or Commercial Shellfishing May Occur 2.3 - Daily Limit 2.4 - Landing Shellfish 2.5 - Daily Time Limit 2.6 - Closures and Red Flag 2.7 - Temperature Restrictions 2.8 - Habitat Sensitive Areas 2.9 - Bay Scallop Strandings 2.10 - Poaching 2.11 - Disturbance of Licensed or Closed Areas 2.12 - Inspection on Demand 2.13 - Possession of Seed 2.14 - Methods of Taking 2.15 – SCUBA Diving and Snorkeling 2.16 - Transplanting, Shipping, and Storing of Live Shellfish 2.16a - Transplanting Shellfish Outside Town Waters 2.16b - Shipping of Live Shellfish for Broodstock Purposes 2.16c - Transplanting Shellfish into Town Waters 2.16d - Harvesting Seed from the Wild Not Allowed 2.16e - Wet Storage of Recreational Shellfish Prohibited. 2.17 - By-Catch 2.18 - Catch Reports Provided to the Town 2.18a - Commercial Catch Reports 2.18b - Recreational Catch Reports Section 3 – Recreational (Non-commercial) Shellfishing 3.1 - Permits 3.1a - No Transfers or Refunds 3.1b - Recreational License Fees 3.2 - Cannot Harvest for Commerce -

Cook's Basics Cook's Basics Cook's Basics

cook'scook's basics basics Helen of Troy bathed in it, biblical figures drank it, Hippocrates prescribed it as medicine, soldiers cleaned their wounds with it during World War I, and today, it is one of the most healthful and widely used condiments. What is this miraculous substance you ask? It's simply vinegar, the product of the fermentation of acetic acid and water. Its beginnings have been traced back 7,000 years ago to the Sumerian civilization, where it was utilized for it cleaning. ALL Today, vinegar is used for innumerable ABOUT BIVALVES To give you the lowdown on bivalves, we shuck these hard-shelled aquatic creatures Words Marisse Gabrielle reyes styling yOyO ZHOU photographs CHarles Chua rECIPE MUriel OpianO Amable RecipE imagE 123rF Brain-less and mostly eye-less and sedentary, these strange creatures are actually living relics of ancient aquatic life. Although their roots trace back to over 500 million years ago, there are currently over 9,000 species of bivalves, with many of them edible. These filter feeders have evolved to include a hard and heavy hinged shell to protect them from predators and other elements. This armor makes them slow-moving and, unfortunately for them, easy to catch. In the case of venus clams, la-la, and cockles, bivalves can be cheap and plentiful. But in the case of oysters, scallops, and abalone, bivalves can be among the most luxurious and expensive foods. These interesting animals can be found in virtually every body of water (such as salty oceans, brackish lakes, and freshwater canals); can be farmed or wild caught; can be eaten raw or cooked; and can be found all over the world.