Feeling Like a Holy Warrior: Western Authors' Attributions of Emotion As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Historical Association

ANNUAL REPORT OP THB AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE YEAR 1913 IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I WASHINGTON 1916 LETTER OF SUBMITTAL. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, Washington, D. O., September '131, 1914. To the Oongress of the United States: In accordance with the act of incorporation o:f the American His toricaJ Association, approved January 4, 1889, I have the honor to submit to Congress the annual report of the association for the year 1913. I have the honor to be, Very respectfully, your obedient servant, CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Secretary. 3 AOT OF INOORPORATION. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Andrew D. White, of Ithaca, in the State of New York; George Bancroft, of Washington, in the District of Columbia; Justin Winsor, of Cam bridge, in the State of Massachusetts; William F. Poole, of Chicago, in the State of Illinois; Herbert B. Adams, of Baltimore, in the State of Maryland; Clarence W. Bowen, of Brooklyn, in the State of New York, their associates and successors, are hereby created, in the Dis trict of Columbia, a body corporate and politic by the name of the American Historical Association, for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of historical manuscripts, and for kindred purposes in the interest of American history and o:f history in America. Said association is authorized to hold real and Jilersonal estate in the District of Columbia so far only as may be necessary to its lawful ends to an amount not exceeding five hundred thousand dollars, to adopt a constitution, and make by-laws not inconsistent with law. -

World History Chapter 9 Study Guide 9-1 1100-1199 Political History 1

Name:________________________________________ Date:____________________ Period:__________ World History Chapter 9 Study Guide 9-1 1100-1199 Political History 1. Which century corresponds with the years 1100-1199? 2. What Catholic military order was founded in 1119, and were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades, and grew rapidly in membership and power? 3. Who was the king of England from 1100 to 1135, and seized the English throne when his brother died in a hunting accident in 1100, and was considered a harsh but effective ruler, and died without a surviving male heir to the throne? 4. Who was king of England from 1135 to 1154, and his reign was marked by a civil war with his cousin and rival, the Empress Matilda, and was succeeded by her son upon his death in 1154? 5. What civil war in England and Normandy took place between 1135 and 1153, and resulted in a widespread breakdown of law and order? 6. What medieval state existed in northwest Italy from 1115 to 1532? 7. What monarchy on the Iberian Peninsula existed from 1139 to 1910? 8. What major campaign launched from Europe to reclaim the County of Edessa from Muslim forces from 1147 to 1149? 9. Who was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 to 1190, and challenged papal authority and sought to establish German dominance in Western Europe, and died in Asia Minor while leading an army in the Third Crusade, and is considered one of the greatest medieval emperors? 10. Who ruled as king of England from 1154 to 1189, and controlled England, large parts of Wales, the eastern half of Ireland, and the western half of France—an area that would later come to be called the Angevin Empire? 11. -

Salutare Animas Nostras: the Ideologies Behind the Foundation of the Templars

SALUTARE ANIMAS NOSTRAS: THE IDEOLOGIES BEHIND THE FOUNDATION OF THE TEMPLARS A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, HUMANITIES, PHILOSOPHY, AND POLITICAL SCIENCE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By Rev. Fr. Thomas Bailey, OSB NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI MAY 2012 Salutare Animas Nostras 1 Running Head: SALUTARE ANIMAS NOSTRAS Salutare Animas Nostras: The Ideologies Behind the Foundation of the Templars Rev. Fr. Thomas Bailey, OSB Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Thesis Advisor Date Dean of Graduate School Date Salutare Animas Nostras 2 Abstract From beginning to end, the Knights Templar were a mysterious order. Little is known of their origins, and most of their records were destroyed during the suppression in the fourteenth century. In addition, they combined seemingly incompatible objectives: warriors and monks, as well as laity and clergy. This study bridges those divides, providing the historical developments from a secular and religious context. To understand the Templars’ foundation, it needs to be based on a premise that combines the ideologies of the priestly and knightly classes–salvation and the means to attain it. The conclusions were drawn following a multi-disciplinary approach. The primary source materials included the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, patristic authors, medieval literature, canon law, the Templars’ rules, in addition to monastic cartularies and chronicles. The secondary sources were a similar collection from various disciplines. The approach allowed for the examination of the Templars from multiple angles, which helped to highlight their diversified origins. The Knights Templar were the product of a long evolution beginning with the Pauline imagery of the Christian as a soldier battling his/her own spiritual demons and continuing through the call for a crusade to defend the Patrimony of Christ. -

The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich

medieval sermon studies, Vol. 56, 2012, 30–45 The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich Scholars have dealt extensively with the sermon held by Urban II at the Council of Clermont to launch the First Crusade. There is indeed much room for speculation, since the original text has been lost and we have to rely on the reports of it in chronicles. But the scholarly discussion is mostly based on the same sort of sources: the chronicles and their references to letters and charters. Not much attention has been paid so far to the genre of papal synodal sermons in the Middle Ages. In this article, I focus on the tradition of papal oratory, using this background to look at the call for crusade from a new perspective. Firstly, I analyse the versions of the Clermont sermon in the crusading chronicles and compare them with the only address held by Urban II known from a non-narrative source. Secondly, I discuss the sermons of Gregory VII as they are recorded in synodal protocols and in historiography. The results support the view that only the version reported by Fulcher of Chartres corresponds to a sort of oratory common to papal speeches in the eleventh century. The speech that Pope Urban II delivered at Clermont in 1095 to launch the First Crusade is probably one of the most discussed sermons from the Middle Ages. It was a popular motif in medieval chronicles and is still an important source for the history of the crusades.1 Since we only have the reports of chroniclers and not the manuscript of the pope himself, each analysis of this address faces a fundamental problem: even the three writers who attended the Council of Clermont recorded three different versions, quite distinctive both in content and style. -

"Contra Haereticos Accingantur": the Union of Crusading and Anti-Heresy Propaganda

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2018 "Contra haereticos accingantur": The nionU of Crusading and Anti-heresy Propaganda Bryan E. Peterson University of North Florida Suggested Citation Peterson, Bryan E., ""Contra haereticos accingantur": The nionU of Crusading and Anti-heresy Propaganda" (2018). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 808. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/808 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2018 All Rights Reserved “CONTRA HAERETICOS ACCINGANTUR”: THE UNION OF CRUSADING AND ANTI-HERESY PROPAGANDA by Bryan Edward Peterson A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES June, 2018 ii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL The thesis of Bryan Edward Peterson is approved (Date) ____________________________________ _____________________ Dr. David Sheffler ____________________________________ ______________________ Dr. Philip Kaplan ____________________________________ ______________________ Dr. Andrew Holt Accepted for the Department of History: _________________________________ _______________________ Dr. David Sheffler Chair Accepted for the College of Arts and Sciences: _________________________________ -

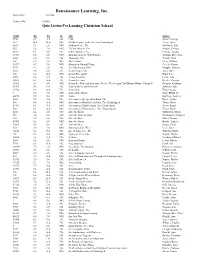

Accelerated Reader List Sorted by Titles in ABC Order (PDF)

Renaissance Learning, Inc. Todays Date: 3/4/2008 Customer No. 134580 Quiz Listing ForLansing Christian School Quiz# RL Pts IL Title Author 5976 8.9 17.0 UG 1984 Orwell, George 523 10.0 28.0 MG 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 6651 3.3 1.0 MG 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 593 5.6 7.0 MG 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 8851 6.1 9.0 UG A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 11901 5.5 4.0 MG Abandoned on the Wild Frontier Jackson, Dave/Neta 6030 6.0 8.0 UG Abduction, The Newth, Mette 101 5.9 3.0 MG Abel's Island Steig, William 11577 4.7 7.0 MG Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 5252 4.2 6.0 UG Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5253 5.6 2.0 UG Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 102 6.6 10.0 MG Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 6901 4.6 8.0 UG Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 18801 6.3 10.0 UG Across the Lines Reeder, Carolyn 17602 5.5 4.0 MG Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon Trail Diary of Hattie Campbell Gregory, Kristiana 11701 4.8 8.0 UG Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me Johnston, Julie 16702 9.4 42.0 UG Adam Bede Eliot, George 1 6.5 9.0 MG Adam of the Road Gray, Elizabeth 64976 5.9 5.0 MG Adara Gormley, Beatrice 8601 7.7 2.0 UG Adventure of the Speckled Band, The Doyle, Arthur 501 6.6 18.0 MG Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The (Unabridged) Twain, Mark 52301 8.1 11.0 MG Adventures of Robin Hood, The (Unabridged) Green, Roger 502 8.1 12.0 MG Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The (Unabridged) Twain, Mark 8551 4.4 5.0 UG After the Bomb Miklowitz, Gloria 351 3.8 8.0 MG After the Dancing Days Rostkowski, Margaret 352 -

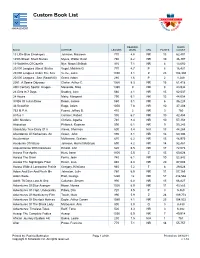

Custom Book List

Custom Book List MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 4.8 NR 15 62,401 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 6.2 NR 10 36,397 19 Varieties Of Gazelle Nye, Naomi Shihab 910 7.1 NR 6 13,050 20,000 Leagues (Great Illustra Vogel, Malvina G. 770 4.7 P 6 16,431 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Verne, Jules 1030 8.1 Z 23 106,330 20,000 Leagues...Sea (Read180) Grant, Adam 280 1.6 P 2 1,289 2001, A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. 1060 8.3 NR 15 61,418 20th Century Sports: Images... Meserole, Mike 1380 9 NR 8 23,934 24 Girls In 7 Days Bradley, Alex 680 4.1 NR 15 62,537 24 Hours Mahy, Margaret 790 6.1 NR 12 44,054 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 5.1 NR 6 36,224 33 Snowfish Rapp, Adam 1050 7.8 NR 10 37,208 763 M.P.H. Fuerst, Jeffrey B. 410 2 NR 3 760 8 Plus 1 Cormier, Robert 930 6.7 NR 10 42,484 ABC Murders Christie, Agatha 740 8.4 NR 10 57,358 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 6.1 NR 9 55,243 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 3.4 N/A 13 44,264 Abundance Of Katherines, An Green, John 890 8.1 NR 16 60,306 Acceleration McNamee, Graham 670 6.2 NR 13 46,975 Accidents Of Nature Johnson, Harriet McBryde 690 4.2 NR 14 52,481 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 6.5 NR 17 72,073 Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 1100 5.5 Z 15 60,628 Across The Grain Ferris, Jean 740 6.1 NR 10 52,842 Across The Nightingale Floor Hearn, Lian 840 6.4 NR 20 87,008 Across Wide & Lonesome Prairie Gregory, Kristiana 940 5.2 T 8 29,628 Adam And Eve And Pinch Me Johnston, Julie 760 6.5 NR 11 57,165 Adam Bede Eliot, George 1260 12 NR 57 216,566 Adrift: 76 Days Lost At Sea Callahan, Steven 990 6.8 NR 15 66,827 Adventures Of Blue Avenger Howe, Norma 1020 6.9 NR 11 43,553 Adventures Of Capt. -

040 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books Mn. VVI LCI AM S1I .A. K- li- S 1^ -A. 1^. t/ S COMEDIES, HISTORICS, & TRAGED1E S. Pulliihid accorv LO 0 Priqtedty like laggard, aod Ed.Blount. 1 <5i}- Facsimile of the title-page of the First Folio Shakespeare, dated 1623 From the original in the New York Public Library, New York THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME I From Chaucer to Gray W//A Introductions and Notes Volume 40 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1910 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. S. A. CONTENTS GEOFFREY CHAUCER PAGE THE PROLOGUE TO THE CANTERBURY TALES n THE NUN'S PRIEST'S TALE 34 TRADITIONAL BALLADS THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY 51 THE TWA SISTERS 54 EDWARD 5 6 BABYLON: OR, THE BONNIE BANKS O FORDIE 58 HIND HORN 59 LORD THOMAS AND FAIR ANNET 61 LOVE GREGOR 65 BONNY BARBARA ALLAN 68 THE GAY GOSS-HAWK 69 THE THREE RAVENS 73 THE TWA CORBIES 74 SIR PATRICK SPENCE 74 THOMAS RYMER AND THE QUEEN OF ELFLAND 76 SWEET WILLIAM'S GHOST 78 THE WIFE OF USHER'S WELL 80 HUGH OF LINCOLN 81 YOUNG BICHAM 84 GET UP AND BAR THE DOOR 87 THE BATTLE OF OTTERBURN 88 CHEVY CHASE 93 JOHNIE ARMSTRONG 101 CAPTAIN CAR 103 THE BONNY EARL OF MURRAY 107 KINMONT WILLIE ' 108 BONNIE GEORGE CAMPBELL 114 THE DOWY HOUMS O YARROW 115 MARY HAMILTON 117 THE BARON OF BRACKLEY 119 BEWICK AND GRAHAME 121 A GEST OF ROBYN HODE 128 1 2 CONTENTS ANONYMOUS PAG* BALOW 186 THE OLD CLOAK 188 JOLLY GOOD ALE AND OLD .. -

The Count of Saint-Gilles and the Saints of the Apocalypse

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2015 The ounC t of Saint-Gilles and the Saints of the Apocalypse: Occitanian Piety and Culture in the Time of the First Crusade Thomas Whitney Lecaque University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Recommended Citation Lecaque, Thomas Whitney, "The ounC t of Saint-Gilles and the Saints of the Apocalypse: Occitanian Piety and Culture in the Time of the First Crusade. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3434 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Thomas Whitney Lecaque entitled "The ounC t of Saint-Gilles and the Saints of the Apocalypse: Occitanian Piety and Culture in the Time of the First Crusade." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Jay Rubenstein, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Burman, Jacob Latham, Rachel Golden Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official student records.) The Count of Saint-Gilles and the Saints of the Apocalypse: Occitanian Piety and Culture in the Time of the First Crusade A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Thomas Whitney Lecaque August 2015 ii Copyright © 2015 by Thomas Whitney Lecaque All rights reserved. -

Communities of Saint Martin

Communities ofSa int Martin Communities of Saint Martin LEGEND AND RITUAL IN MEDIEVAL TouRs Sharon Farmer Cornell University Press ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1991 by Cornell University First paperback printing 2019 The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2391-8 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-4059-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-4060-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-4061-9 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Cover illustration: Saint Martin. Courtesy of Bibliothèque Municpale, Tours. Contents List of Illustrations vii List of Tables Vlll Preface lX Introduction I PART I. MARTIN's TowN: FROM UNITY TO DuALITY Introduction 1 I 1. Martinopolis (ca. 37I-I050) 13 2. Excluding the Center: Monastic Exemption and Liturgical Realignment in Tours 38 PART 2. MARMOUTIER Introduction 65 3. History, Legitimacy, and Motivation in Marmoutier's Literature fo r the Angevins 78 4· Marmoutier and the Salvation of the Counts of Blois 96 5· Individual Motivation, Collective Responsibility: Reinforcing Bonds of Community I I 7 6. -

Peter the Hermit: Straddling the Boundaries of Lordship, Millennialism, and Heresy Stanley Perdios Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 peter the hermit: straddling the boundaries of lordship, millennialism, and heresy Stanley Perdios Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Perdios, Stanley, "peter the hermit: straddling the boundaries of lordship, millennialism, and heresy" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12431. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12431 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peter the Hermit: Straddling the boundaries of lordship, millennialism, and heresy by Stelios Vasilis Perdios A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Michael D. Bailey, Major Professor John W. Monroe Jana Byars Kevin Amidon Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Stelios Vasilis Perdios, 2012. All Rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Chapter Page Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Crisis of Secular Lordship 7 Chapter Three: The Crisis of Spiritual Lordship 35 Chapter Four: Lordship on the Eve of the Millennium 65 Chapter Five: Conclusion 95 Bibliography 99 1 Chapter One: Introduction When is a hermit not a hermit? When he is Peter the Hermit who led the Popular Crusade in the year 1096. -

Indulgences: Practice V. Theology Caitlin Vest This Paper Was Written for Dr

Indulgences: Practice v. Theology Caitlin Vest This paper was written for Dr. Shirley!s Medieval Church and Papacy course. It was presented at the 2009 Regional Phi Alpha Theta Conference at St. Leo University. It is presented here in abstract. In 1095, Pope Urban II granted the first full – or plenary – indulgence to those who died fighting, or intending to fight, the Muslims in the First Crusade. Soon, indulgences were used to raise an army and revenue for the Catholic Church. The increased use of indulgences led to a dramatic increase in the power of the Medieval papacy. It was not until a century after the first use of indulgences, however, that the theology of indulgences began to be developed. The fact that the practice of granting indulgences preceded the development of indulgence theology suggests that indulgences were necessary for reasons unrelated to theology. A plenary indulgence was the complete remission of penance for sin. This remission required no service or exchange from the penitent. All forms of commutations and indulgences required the penitent to have confessed and received absolution. These different types of indulgences evolved over time based on the needs of the church. They allowed the Church to compete with secular powers and also clearly defined the church hierarchy, headed by the pope. Having developed the practice of granting indulgences, the church needed to develop a theology to support it. Because of the belief that the Church was infallible, it was necessary to create theology to support the Church!s practice. The theology was influenced by, and served to justify, the practice.