To Ask Freedom for Women 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Form Teacher's Guide for Fight of the Century: Alice Paul

Long-Form Teacher’s Guide for Fight of the Century: Alice Paul Battles Woodrow Wilson for the Vote by Barb Rosenstock and illustrated by Sarah Green Book Synopsis When Woodrow Wilson was elected President, he didn't know that he would be participating in one of the greatest fights of the century: the battle for women's right to vote. The formidable Alice Paul was a leader in the women's suffrage movement and saw President Wilson's election as an opportunity to win the vote for women. She battered her opponent with endless strategic arguments and carefully coordinated protests, calling for a new amendment granting women the right to vote. With a spirit and determination that never quit--even when peaceful protests were met with violence and even when many women were thrown in jail--Paul eventually convinced President Wilson to support her cause, changing the country forever. Cleverly framed as a boxing match, this book provides a fascinating and compelling look at an important moment in American history. Historical Background Alice Paul was born on January 11, 1885 to Tracie and William Paul in New Jersey. Raised as a Quaker, she and her siblings learned the importance of equality and education, believing that women and men were equal and deserved equal rights in society. In the early 1900s, Alice attended the Universities of London and Birmingham and while there she joined the Women's Social and Political Union, a suffragette organization founded by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903. (It is important to note that the term “suffragette” was only used in relation to the suffrage movement in England, while the term “suffragist” was used in relation to the movement in the United States). -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Women's Suffrage Movement

Women’s Suffrage Movement 15th Amendment Things to think about… The right of citizens . Did this law help women of the United States achieve their goal? to vote shall not be denied or abridged . How would you feel if by the United States you were a woman at or by any state on this time? account of race, . Were the methods the color, or previous women were using condition of effective? servitude. Alice Paul (1885-1977) . Very well educated Quaker . Influenced by Pankhursts – Leaders of the British suffrage movement . Engaged in direct action-disrupting male meetings and breaking windows. Alice joined their struggle . 1912- returns to US and joins forces with Lucy Burns . Dramatic Woman Suffrage Procession the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson- 1913 . 1916 – National Woman’s Party – more radical group . 1917-Picket the White House-”Silent Sentinels” Silent Sentinels Lucy Burns in prison .1918- Wilson came out in support of the amendment- .Took more than 2 years for the measure to pass Congress .19th amendment was finally approved in 1920 .http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gj YtacfcgPU Carrie Chapman Catt . 1880 – she was the only woman among 18 graduates . Became a paid suffrage organizer . She would write, speak, lobby, organize, campaign and get support through persuasion . Anthony’s hand picked successor . 1916- winning plan to press for the vote and the local, state, and federal levels . Supervised the campaign that won the vote for women in NYS . 1918- Wilson came out in support of the suffrage amendment 1920- 19th amendment is passed. Tennessee was the final state to approve the amendment- by 1 vote . -

2010 Women's Committee Report

Report of the CWANational Women's Committee to the 72nd Annual Convention Communications Workers of America July 26-28, 2010 Washington, D.C. Introduction The National Women's Committee is deviating from our usual reporting format this year to celebrate and acknowledge two historic anniversaries in the women's suffrage movement. First, this year marks the 90th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, granting women full voting rights. The committee members are wearing gold, white and purple sashes like the ones worn by the suffragettes in parades and demonstrations. The color gold signifies coming out of darkness into light, white stands for purity and purple is a royal color which represents victory. The committee members will now introduce you to six courageous women who fought to obtain equal rights and one which continues that fight today. 1 Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm I November 30, 1924 - January 1, 2005 Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was born Novem- several campus and community groups where she ber 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York, to Barbadi- developed a keen interest in politics. an parents. Chisholm was raised in an atmosphere that was both political and religious. Chisholm After graduating cum laude from Brooklyn received much of her primary education in her College in 1946, Chisholm began to work as a parents' homeland, Barbados, under the strict nursery school teacher and later as a director of eye of her maternal grandmother. Chisholm, who schools for early childhood education. In 1949 returned to New York when she was ten years she married Conrad Chisholm, a Jamaican who old, credits her educational successes to the well- worked as a private investigator. -

“Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”1

“Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”1 Mallory Durlauf Junior Division Individual Historical Paper Women, it rests with us. We have got to bring to the President, individually, day by day, week in and week out, the idea that great numbers of women want to be free, will be free, and want to know what he is going to do about it. - Harriot Stanton Blatch, 19172 An important chapter in American history is the climax of the battle for woman suffrage. In 1917, members of the National Woman’s Party escalated their efforts from lobbying to civil disobedience. These brave women aimed their protests at President Woodrow Wilson, picketing the White House as “Silent Sentinels” and displaying statements from Wilson’s speeches to show his hypocrisy in not supporting suffrage. The public’s attention was aroused by the arrest and detention of these women. This reaction was strengthened by the mistreatment of the women in jail, particularly their force-feeding. In 1917, when confronted by the tragedy of the jailed suffragists, prominent political figures and the broader public recognized Wilson’s untenable position that democracy could exist without national suffrage. The suffragists triumphed when Wilson changed his stance and announced his support for the federal suffrage amendment. The struggle for American woman suffrage began in 1848 when the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. The movement succeeded in securing suffrage for four states, but slipped into the so-called “doldrums” period (1896-1910) during which no states adopted suffrage.3 After the Civil War, the earlier suffrage groups merged into the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but their original aggressiveness waned.4 Meanwhile, in Britain, militant feminism had appeared. -

“Inciting a Riot”: Silent Sentinels, Group Protests, and Prisoners’ Petition and Associational Rights

“Inciting a Riot”: Silent Sentinels, Group Protests, and Prisoners’ Petition and Associational Rights Nicole B. Godfrey* CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................1113 I. THE SUFFRAGISTS’ PROTESTS ..........................................................1118 A. Alice Paul and Lessons Learned from the Suffragettes ..............1119 B. The Silent Sentinels’ Protests .....................................................1120 C. In-Prison Petitions and Protests ................................................1123 II. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND PRISONER PETITION AND ASSOCIATIONAL RIGHTS .....................................................................1130 A. Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc.................1132 B. The Flaws of Deference to Prison Officials ...............................1135 III. IMPORTANCE OF PROTECTING PRISONER ASSOCIATIONAL AND PETITION RIGHTS .................................................................................1139 A. “Inciting a Riot” .........................................................................1140 B. Modern Prisoner Protests ...........................................................1143 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................1145 INTRODUCTION In January 1917, a group of women led by Alice Paul began a two- and-a-half year protest in support of women’s suffrage.1 As the first activists to ever picket the White House,2 these women became known as * Visiting -

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

REMEMBER: UPDATE THE FOLIO THE COUNTY COLLEGE OF MORRIS’ AWARD-WINNING STUDENT NEWSPAPER YOUNGTOWN VOL. 105, NO. 3 WEDNESDAY, OCT. 14, 2020 EDITION RANDOLPH, N.J. CCM commemorates centennial anniversary of 19th amendment BY ADAM GENTILE Editor-in-Chief The ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 recognized a woman’s right to vote in the United States. To celebrate the centennial anniversary of the historic event CCM Professor Mark Washburne, of the his- tory and political science de- partment, hosted Dr. Rozella G. Clyde, education director for the Morristown chapter of the League of Women Voters (LWV) on Sept. 30. Clyde provided stu- dents with a brief history of the women’s suffrage movement. Formed in 1919, the LWV is a nonpartisan grassroots or- ganization that worked in as- PHOTO COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS sociation with the National PHOTO BY BUCK G.V PHOTO COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Susan B. Anthony (sitting) and Elizabeth Cady American Woman Suffrage As- Suffrage March in New York City circa 1912. Stanton. sociation (NAWSA), according to the LWV Morristown’s web- of the 1830s and 1840s. Notable adopted strategies from aboli- Women’s Suffrage Associa- “The years leading up to site after the passing of the 19th abolitionist Frederick Douglass tionists, such as hosting rallies, tion (AWSA) founded by Lucy World War 1 were really im- amendment, the LWV replaced spoke at the Seneca Falls Con- speaking at public meetings, and Stone, Henry Brown Blackwell, portant,” Clyde said. “Because the NAWSA. vention, an event dedicated to even implementing economic among others. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

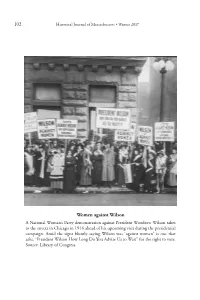

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

Silent Sentinels and Hunger Strikes (1917-1919)

1 Silent Sentinels and Hunger Strikes (1917-1919) National Woman’s Party picketing the White House in 1917. Courtesy of Library of Congress. On January 10, 1917, Alice Paul and a dozen women from the National Woman’s Party were fi rst people to ever picket the White House. For nearly two and a half years, almost 2000 women engaged in picketing outside the White House six days a week until June 4, 1919, when the suff rage amendment fi nally passed both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. Calling themselves the “Silent Sentinels,” the women carried banners with messages such as: “Mr. President - How Long Must Women Wait For Liberty?” and “Mr. President – What Will You Do For Woman Suff rage?” In the wake of World War I, the banners accused President Wilson of hypocrisy for fi ghting for world democracy while leaving American women without rights. One year after the picketing began, President Wilson announced his support for the suff rage amendment. The suff ragists continued their protest and were harassed, arrested, jailed, and even force fed when they went on hunger strikes in the Occoquan Workhouse prison. On the night of November 14, 1917, known as the “Night of Terror,” the prison superintendent ordered forty guards to brutalize the imprisoned suff ragists, who were chained, beaten, choked, and tortured. Their mistreatment angered many Americans and created more support for the suff rage movement. By the time the suff rage amendment passed, a U.S. Court of Appeals had also cleared the suff ragists of charges for their civil disobedience, creating important legal precedents that paved the way for generations of protestors.