“Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1925 Monkey Trial

The “Monkey Trial” March 1925. • On 21st March 1925 Tennessee passed the Butler Act which stated: • That it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the Story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals. Proposer of the act: John Washington Butler. Religion vs. Science. • (State Representative) John W. Butler, a Tennessee farmer and head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, lobbied state legislatures to pass the anti-evolution law. The act is challenged. • John Thomas Scopes' involvement in the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial came about after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case challenging the constitutionality of the Butler Act if they could find a Tennessee teacher willing to act as a defendant. • Photograph of John Scopes taken one month before the trial. Opportunistic Bush Lawyers? • A band of businessmen in Dayton, Tennessee, led by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea, saw this as an opportunity to get publicity for their town and approached Scopes. • Rappleyea pointed out that while the Butler Act prohibited the teaching of human evolution, the state required teachers to use the assigned textbook, Hunter's Civic Biology (1914), which included a chapter on evolution. • Rappleyea argued that teachers were essentially required to break the law. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

The Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan Kari Lynn Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Kari Lynn, "Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 96. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/96 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIX DAYS OF TWENTY-FOUR HOURS: THE SCOPES TRIAL, ANTIEVOLUTIONISM, AND THE LAST CRUSADE OF WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by KARI EDWARDS May 2012 Copyright Kari Edwards 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The academic study of the Scopes Trial has always been approached from a traditional legal interpretation. This project seeks to reframe the conventional arguments surrounding the trial, treating it instead as a significant religious event, one which not only altered the course of Christian Fundamentalism and the Creationist movement, but also perpetuated Southern religious stereotypes through the intense, and largely negative, nationwide publicity it attracted. Prosecutor William Jennings Bryan's crucial role is also redefined, with his denial of a strictly literal interpretation of Genesis during the trial serving as the impetus for the shift toward ultra- conservatism and young-earth Creationism within the movement after 1925. -

Ally Advocacy, Identity Reconfiguration, and Political Change

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “THE FIGHT IS YOURS”: ALLY ADVOCACY, IDENTITY RECONFIGURATION, AND POLITICAL CHANGE William Howell, Doctor of Philosophy, 2020 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Trevor Parry-Giles, Department of Communication Since at least 1990, scholars and activists have used the term “ally” to describe and theorize a distinct sociopolitical role: someone from a majority identity group working to end that group’s oppression of another identity group. While the term is recent, “allies” are present throughout America’s constant struggle to actualize equality and justice. The identity-rooted ideologies that empowered allies disempowered the groups for and with whom they sought justice and equality. But those empowering identities were pieces, more or less salient, of complex intersectional people. Given the shared nature of identity, this process also necessarily pitted allies against those with whom they shared an identity. In this project, I ask two questions about past ally advocacy—questions that are often asked about contemporary ally advocacy. First, in moments of major civil rights reform, how did allies engage their own intersecting identities—especially those ideologically-charged identities with accrued power from generations of marginalizing and oppressing? Second, how did allies engage other identities that were not theirs—especially identities on whose oppression their privilege was built? In asking these two questions—about self-identity and others’ identity—I assemble numerous rhetorical fragments into “ally advocacy.” This bricolage is in recognition of rhetoric’s fragmentary nature, and in response to Michael Calvin McGee’s call to assemble texts for criticism. I intend to demonstrate that ally advocacy is such a text, manifesting (among other contexts) around the women’s suffrage amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the marriage equality movement. -

The Roosevelt Myth

THE ROOSEVELT MYTH BY JOHN T. FLYNN (1948) Flynn was a political reporter who supported the populist objectives of FDR early in his career but became an ardent critic later on, as he saw the blunders and corruption of the Roosevelt administration covered up by a compliant press. FDR was always portrayed as a peace-loving populist on the side of the "little guy" while many of his advisors were war mongers, communist sympathizers, and agents of Wall Street. This expose is a much needed corrective to the 'myth' of Roosevelt populism. TABLE OF CONTENTS BOOK I: TRIAL AND ERROR NEW DEALER TAKES THE DECK ............................................................... 3 THE HUNDRED DAYS ....................................................................................................................................... 7 THE BANKING CRISIS .................................................................................................................................... 11 THE NEW NEW DEAL..................................................................................................................................... 21 THE RABBITS GO BACK IN THE HAT ............................................................................................................ 26 THE DANCE OF THE CRACKPOTS ................................................................................................................. 38 AN ENEMY IS WELCOMED ............................................................................................................................ -

Carol Inskeep's Book List on Woman's Suffrage

Women’s Lives & the Struggle for Equality: Resources from Local Libraries Carol Inskeep / Urbana Free Library / [email protected] Cartoon from the Champaign News Gazette on September 29, 1920 (above); Members of the Chicago Teachers’ Federation participate in a Suffrage Parade (right); Five thousand women march down Michigan Avenue in the rain to the Republican Party Convention hall in 1916 to demand a Woman Suffrage plank in the party platform (below). General History of Women’s Suffrage Failure is Impossible: The History of American Women’s Rights by Martha E. Kendall. 2001. EMJ From Booklist - This volume in the People's History series reviews the history of the women's rights movement in America, beginning with a discussion of women's legal status among the Puritans of Boston, then highlighting developments to the present. Kendall describes women's efforts to secure the right to own property, hold jobs, and gain equal protection under the law, and takes a look at the suffrage movement and legal actions that have helped women gain control of their reproductive rights. She also compares the lifestyles of female Native Americans and slaves with those of other American women at the time. Numerous sepia photographs and illustrations show significant events and give face to important contributors to the movement. The appended list of remarkable women, a time line, and bibliographies will further assist report writers. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement by Sally G. McMillen. 2008. S A very readable and engaging account that combines excellent scholarship with accessible and engaging writing. -

2010 Women's Committee Report

Report of the CWANational Women's Committee to the 72nd Annual Convention Communications Workers of America July 26-28, 2010 Washington, D.C. Introduction The National Women's Committee is deviating from our usual reporting format this year to celebrate and acknowledge two historic anniversaries in the women's suffrage movement. First, this year marks the 90th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, granting women full voting rights. The committee members are wearing gold, white and purple sashes like the ones worn by the suffragettes in parades and demonstrations. The color gold signifies coming out of darkness into light, white stands for purity and purple is a royal color which represents victory. The committee members will now introduce you to six courageous women who fought to obtain equal rights and one which continues that fight today. 1 Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm I November 30, 1924 - January 1, 2005 Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was born Novem- several campus and community groups where she ber 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York, to Barbadi- developed a keen interest in politics. an parents. Chisholm was raised in an atmosphere that was both political and religious. Chisholm After graduating cum laude from Brooklyn received much of her primary education in her College in 1946, Chisholm began to work as a parents' homeland, Barbados, under the strict nursery school teacher and later as a director of eye of her maternal grandmother. Chisholm, who schools for early childhood education. In 1949 returned to New York when she was ten years she married Conrad Chisholm, a Jamaican who old, credits her educational successes to the well- worked as a private investigator. -

“Inciting a Riot”: Silent Sentinels, Group Protests, and Prisoners’ Petition and Associational Rights

“Inciting a Riot”: Silent Sentinels, Group Protests, and Prisoners’ Petition and Associational Rights Nicole B. Godfrey* CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................1113 I. THE SUFFRAGISTS’ PROTESTS ..........................................................1118 A. Alice Paul and Lessons Learned from the Suffragettes ..............1119 B. The Silent Sentinels’ Protests .....................................................1120 C. In-Prison Petitions and Protests ................................................1123 II. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND PRISONER PETITION AND ASSOCIATIONAL RIGHTS .....................................................................1130 A. Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc.................1132 B. The Flaws of Deference to Prison Officials ...............................1135 III. IMPORTANCE OF PROTECTING PRISONER ASSOCIATIONAL AND PETITION RIGHTS .................................................................................1139 A. “Inciting a Riot” .........................................................................1140 B. Modern Prisoner Protests ...........................................................1143 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................1145 INTRODUCTION In January 1917, a group of women led by Alice Paul began a two- and-a-half year protest in support of women’s suffrage.1 As the first activists to ever picket the White House,2 these women became known as * Visiting -

Creating a Primary Source Lesson Plan

Women’s Fight for Equality Katy Mullen and Scott Gudgel Stoughton High School London arrest of suffragette. Bain News Service. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-ggbain-10397, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.10397/ This unit on women in US History examines gender roles, gender stereotypes, and interpretations of significant events in women’s history. This leads students to discover gender roles in contemporary society. Overview Objectives: Students will: Knowledge • Analyze women’s history and liberation • Analyze the different interpretations of significant historical events Objectives: Students will: Skills • Demonstrate critical thinking skills • Develop writing skills • Collaborative Group work skills Essential “Has the role of women changed in the United States?” Question Recommended 13 50-minute class periods time frame Grade level 10th –12th grade Materials Copies of handouts Personal Laptops for students to work on Missing! PowerPoint. Library time Wisconsin State Standards B.12.2 Analyze primary and secondary sources related to a historical question to evaluate their relevance, make comparisons, integrate new information with prior knowledge, and come to a reasoned conclusion B.12.3 Recall, select, and analyze significant historical periods and the relationships among them B.12.4 Assess the validity of different interpretations of significant historical events B.12.5 Gather various types of historical evidence, including visual and quantitative data, to analyze issues of -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

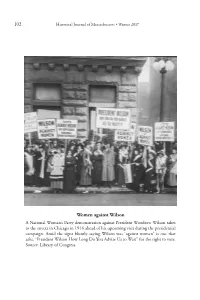

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

National Women's Party Lesson Plan

The National Women’s Party: Jailed for Freedom Lesson Plan by Erica W. Benson; M.A. North American History, M.A. Secondary Education: Teaching, B.A. History, B.S. Journalism Objective: • Was the justice system fair and Constitutional in its treatment of the National Women’s Party picketers? • What role did the Occoquan Workhouse play in the women’s suffrage movement? Grade Level: 9th- 12th Time Frame: • At least one 45/50-minute class period, if you plan it for a longer class period you have the opportunity to show clips of the HBO film Iron Jawed Angels. • Question 13 can be assigned for homework and submitted online or written by hand. Pre-requisites: It is helpful if students have studied WWI so they can understand the context of the final push for suffrage and the messaging and strategy used by the NWP to pressure President Wilson. Materials: • Primary Source Document sets for pair groupings (upload online if students have computers or print) • Phased guided questions/position questions – one copy for each student • A projector to play film clips (you can typically find Iron Jawed Angels for free online, or you can purchase the DVD – you won’t regret it!) Procedures: Step-by-step plan of instruction: 1. Open the class with a 3-minute quick write: “What free speech rights do Americans have? Is it ever limited, if so, when?” After a few minutes post/reveal the 1st Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” a.