Chipman, Fanny S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1925 Monkey Trial

The “Monkey Trial” March 1925. • On 21st March 1925 Tennessee passed the Butler Act which stated: • That it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the Story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals. Proposer of the act: John Washington Butler. Religion vs. Science. • (State Representative) John W. Butler, a Tennessee farmer and head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, lobbied state legislatures to pass the anti-evolution law. The act is challenged. • John Thomas Scopes' involvement in the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial came about after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case challenging the constitutionality of the Butler Act if they could find a Tennessee teacher willing to act as a defendant. • Photograph of John Scopes taken one month before the trial. Opportunistic Bush Lawyers? • A band of businessmen in Dayton, Tennessee, led by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea, saw this as an opportunity to get publicity for their town and approached Scopes. • Rappleyea pointed out that while the Butler Act prohibited the teaching of human evolution, the state required teachers to use the assigned textbook, Hunter's Civic Biology (1914), which included a chapter on evolution. • Rappleyea argued that teachers were essentially required to break the law. -

The Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan Kari Lynn Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Kari Lynn, "Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 96. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/96 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIX DAYS OF TWENTY-FOUR HOURS: THE SCOPES TRIAL, ANTIEVOLUTIONISM, AND THE LAST CRUSADE OF WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by KARI EDWARDS May 2012 Copyright Kari Edwards 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The academic study of the Scopes Trial has always been approached from a traditional legal interpretation. This project seeks to reframe the conventional arguments surrounding the trial, treating it instead as a significant religious event, one which not only altered the course of Christian Fundamentalism and the Creationist movement, but also perpetuated Southern religious stereotypes through the intense, and largely negative, nationwide publicity it attracted. Prosecutor William Jennings Bryan's crucial role is also redefined, with his denial of a strictly literal interpretation of Genesis during the trial serving as the impetus for the shift toward ultra- conservatism and young-earth Creationism within the movement after 1925. -

Ally Advocacy, Identity Reconfiguration, and Political Change

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “THE FIGHT IS YOURS”: ALLY ADVOCACY, IDENTITY RECONFIGURATION, AND POLITICAL CHANGE William Howell, Doctor of Philosophy, 2020 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Trevor Parry-Giles, Department of Communication Since at least 1990, scholars and activists have used the term “ally” to describe and theorize a distinct sociopolitical role: someone from a majority identity group working to end that group’s oppression of another identity group. While the term is recent, “allies” are present throughout America’s constant struggle to actualize equality and justice. The identity-rooted ideologies that empowered allies disempowered the groups for and with whom they sought justice and equality. But those empowering identities were pieces, more or less salient, of complex intersectional people. Given the shared nature of identity, this process also necessarily pitted allies against those with whom they shared an identity. In this project, I ask two questions about past ally advocacy—questions that are often asked about contemporary ally advocacy. First, in moments of major civil rights reform, how did allies engage their own intersecting identities—especially those ideologically-charged identities with accrued power from generations of marginalizing and oppressing? Second, how did allies engage other identities that were not theirs—especially identities on whose oppression their privilege was built? In asking these two questions—about self-identity and others’ identity—I assemble numerous rhetorical fragments into “ally advocacy.” This bricolage is in recognition of rhetoric’s fragmentary nature, and in response to Michael Calvin McGee’s call to assemble texts for criticism. I intend to demonstrate that ally advocacy is such a text, manifesting (among other contexts) around the women’s suffrage amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the marriage equality movement. -

The Roosevelt Myth

THE ROOSEVELT MYTH BY JOHN T. FLYNN (1948) Flynn was a political reporter who supported the populist objectives of FDR early in his career but became an ardent critic later on, as he saw the blunders and corruption of the Roosevelt administration covered up by a compliant press. FDR was always portrayed as a peace-loving populist on the side of the "little guy" while many of his advisors were war mongers, communist sympathizers, and agents of Wall Street. This expose is a much needed corrective to the 'myth' of Roosevelt populism. TABLE OF CONTENTS BOOK I: TRIAL AND ERROR NEW DEALER TAKES THE DECK ............................................................... 3 THE HUNDRED DAYS ....................................................................................................................................... 7 THE BANKING CRISIS .................................................................................................................................... 11 THE NEW NEW DEAL..................................................................................................................................... 21 THE RABBITS GO BACK IN THE HAT ............................................................................................................ 26 THE DANCE OF THE CRACKPOTS ................................................................................................................. 38 AN ENEMY IS WELCOMED ............................................................................................................................ -

Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Författare: Olga Grinchtein © Handledare: Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Vårterminen 2021 ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Olga Grinchtein Titel och undertitel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Engelsk titel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Handledare Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Ventileringstermin: Höstterm. (år) Vårterm. (år) Sommartermin (år) 2021 The portrait of sculptor emerged in the sixteenth century, where the sitter’s occupation was indicated by his holding a statue. This thesis has focus on portraits of sculptors at the turn of 1900, which have indications of profession. 60 artworks created between 1872 and 1927 are analyzed. The goal of the thesis is to identify new facets that modernism introduced to the portraits of sculptors. The thesis covers the evolution of artistic convention in the depiction of sculptor. The comparison of portraits at the turn of 1900 with portraits of sculptors from previous epochs is included. The thesis is also a contribution to the bibliography of portraits of sculptors. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Karin Wahlberg Liljeström for her help and advice. I also thank Linda Hinners for providing information about Annie Bergman’s portrait of Gertrud Linnea Sprinchorn. I would like to thank my mother for supporting my interest in art history. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

“Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”1

“Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”1 Mallory Durlauf Junior Division Individual Historical Paper Women, it rests with us. We have got to bring to the President, individually, day by day, week in and week out, the idea that great numbers of women want to be free, will be free, and want to know what he is going to do about it. - Harriot Stanton Blatch, 19172 An important chapter in American history is the climax of the battle for woman suffrage. In 1917, members of the National Woman’s Party escalated their efforts from lobbying to civil disobedience. These brave women aimed their protests at President Woodrow Wilson, picketing the White House as “Silent Sentinels” and displaying statements from Wilson’s speeches to show his hypocrisy in not supporting suffrage. The public’s attention was aroused by the arrest and detention of these women. This reaction was strengthened by the mistreatment of the women in jail, particularly their force-feeding. In 1917, when confronted by the tragedy of the jailed suffragists, prominent political figures and the broader public recognized Wilson’s untenable position that democracy could exist without national suffrage. The suffragists triumphed when Wilson changed his stance and announced his support for the federal suffrage amendment. The struggle for American woman suffrage began in 1848 when the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. The movement succeeded in securing suffrage for four states, but slipped into the so-called “doldrums” period (1896-1910) during which no states adopted suffrage.3 After the Civil War, the earlier suffrage groups merged into the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but their original aggressiveness waned.4 Meanwhile, in Britain, militant feminism had appeared. -

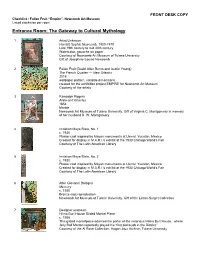

Checklist by Room

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I. -

Antoine Bourdelle, Grand Guerrier / 2019 1

e XIX siècle / France / Sculpture Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen – Parc des sculptures Étude d’une œuvre… ANTOINE BOURDELLE (Montauban, 1861 – Le Vésinet, 1929) Grand Guerrier 1894-1900 Fiche technique Bronze 212 x 154 x 59 cm Dépôt du Musée Bourdelle Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen / Étude d’une œuvre : Antoine Bourdelle, Grand Guerrier / 2019 1 ÉLÉMENTS BIOGRAPHIQUES 1861 : Naissance à Montauban, son père est menuisier, il en gardera un attachement important au savoir-faire, à la technicité. Il entre à 15 ans à l'École des beaux-arts de Toulouse. 1893 : Il intègre l’atelier de Rodin où il est engagé comme praticien (c'est-à- dire simple exécutant). Il collabore plus de quinze ans avec le maître. Il participe entre autres à la réalisation des Bourgeois de Calais et devient un proche de Rodin. 1900 : Bourdelle s’émancipe peu à peu de l’emprise artistique de Rodin avec sa Tête d’Apollon . 1905 : Sa première exposition personnelle est organisée par le fondeur Hebrard qui, en le dispensant des frais de fonte, lui octroie une liberté opportune. 1908 : Il quitte définitivement l’atelier de Rodin. 1909 : Il réalise Héraclès archer et commence à enseigner à la Grande Chaumière où il aura pour élèves de nombreux artistes tels qu’Alberto Giacometti, Germaine Richier ou encore Maria Helena Vieira Da Silva. 1913 : Il conçoit le décor de la façade et les reliefs de l'atrium du théâtre des Champs-Élysées construit par Auguste Perret. À l’Armory Show, première manifestation d'art contemporain sur le sol américain, les œuvres de Bourdelle côtoient celles de Duchamp, Brancusi ou Picabia. -

Bourdelle (1861-1929)

Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929) Né à Montauban (Tarn et Garonne) le 30 octobre 1861, Antoine Bourdelle est le petit- fils d’un chevrier et le fils d’un menuisier- ébéniste. A 13 ans, il quitte l’école pour devenir apprenti auprès de son père et apprend à tailler le bois. Le soir, il suit des cours de dessin et de modelage et se fait remarquer des amateurs montalbanais. En 1876, il obtient une bourse pour étudier à l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Toulouse, il a 15 ans. En 1884, il vient à Paris et, reçu second au concours d’admission, entre à l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, dans l’atelier du sculpteur Alexandre Falguière (1831-1900). Il reçoit aussi les conseils de Jules Dalou. Il quitte Falguière en 1887, mais gardera toujours de l’estime pour son ancien maître. En 1885, i loue un atelier à Montparnasse où il vit et travaille jusqu’à sa mort : c’est aujourd’hui le musée Bourdelle. Il participe pour la première fois au Salon des Artistes Français. A partir de 1891, il expose au Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. En 1888, apparaît la figure de Beethoven , un motif qu’il reprendra tout au long de sa vie. Pour gagner sa vie, il entre en 1893 comme praticien dans l’atelier de Rodin : il y reste 15 ans (jusqu’en 1908) et une véritable amitié s’établit entre les deux hommes. En 1895, il reçoit de sa ville natale la commande du Monument aux Combattants et Défenseurs du Tarn- et-Garonne de 1870 (1897-1900). -

BEACON PRESS Random House Adult Green

BEACON PRESS Random House Adult Green Omni, Fall 2013 Beacon Press Gaga Feminism : Sex, Gender, and the End of Summary: A roadmap to sex and gender for the twenty- Normal first century, using Lady Gaga as a symbol for a new kind J. Jack Halberstam of feminism 9780807010976 Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 Why are so many women single, so many men resisting $16.00/$18.00 Can. marriage, and so many gays and lesbians having babies? 184 pages Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) In Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal, J. Social Science / Gender Studies Jack Halberstam answers these questions while attempting to Territory: World except United Kingdom make sense of the tectonic cultural shifts that have Ctn Qty: 24 transformed gender and sexual politics in the last few 5.500 in W | 8.500 in H decades. This colorful landscape is popula... 140mm W | 216mm H Author Bio: J. Jack Halberstam is the author of four books, including Female Masculinity and The Queer Art of Failure. Currently a professor of American studies and of ethnicity and gender studies at the University of Southern California, Halberstam regularly speaks and writes on queer culture and gender issues and blogs at BullyBloggers. Random House Adult Green Omni, Fall 2013 Beacon Press The Long Walk to Freedom : Runaway Slave Summary: In this groundbreaking compilation of first-person Narratives accounts of the runaway slave phenomenon, editors Devon Devon W. Carbado, Donald Weise W. Carbado and Donald Weise have recovered twelve 9780807069097 narratives spanning eight decades-more than half of which Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 have been long out of print. -

Emile-Antoine Bourdelle (1861 - 1929)

EMILE-ANTOINE BOURDELLE (1861 - 1929) Head of Apollo on a Square Base or Apollo in Battle Bronze proof with brown patina with rich green nuances and partially gilded Sand-cast by Alexis Rudier, probably between 1913 and 1925 Founder's signature (on the back of the base): ALEXIS RUDIER. FONDEUR. PARIS. Signed and dated (in a cartouche): EMILE ANTOINE BOURDELLE 1900 Note (in the lower part of the cartouche): REPRODUCTION INTERDITE (Reproduction prohibited) Monogrammed (under the right ear): B 67 x 23.7 x 28.2 cm Provenance Sotheby’s, Monaco, 25 November 1979, lot 55 Private European collection Selective bibliography Jianou, Ionel et Dufet, Michel, Bourdelle, 2nd English edition with a complete and numbered catalogue of the sculptures, Arted, 1978, n°266. Lenormand-Romain, Antoinette, « La Tête d’Apollon, la ‘cause du divorce’ entre Rodin et Bourdelle » ("The Head of Apollo, 'the cause of the divorce' between Rodin and Bourdelle"), in. La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France, n°3, June, 1990, p.212-220. De Degas à Matisse, la collection d’art moderne du musée Toulouse- Lautrec, Alès, Musée Bibliothèque Pierre-André Benoit, 2006, repr. p.19 (of the one in the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum). Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929), passeur de la modernité (conveyer of modernity), Bucarest – Paris, une amitié franco-roumaine, exhibition catalogue, Bucarest, Romanian National Museum of Art, September 28, 2005 – January 24, 2006, Paris, Bourdelle Museum, repr. p.187 (of the one in the Bourdelle Museum, Inv. MB br300). Cantarutti, Stéphanie, Bourdelle, Paris, Art en scène, 2013, repr. p.101 (of the one in the Bourdelle Museum, Inv. -

Sparks Letter to the Editor Sourcing Contextualizing Close Reading

WWW. HISTORICALT HINKINGM ATTERS. ORG — SCOPES T RIAL Document A: Sparks Letter to the Editor Many citizens wrote letters to Tennessee’s newspapers in response to the Butler Act. Below is an excerpt from a letter written by a parent. Editor of the Nashville Tennessean: At the time the bill prohibiting the teaching of evolution in our public schools was passed by our legislature I could not see why the mothers in greater number were not conveying their appreciation to the members for this act of safeguarding their children from one of the destructive forces which . will destroy our civilization. I for one felt grateful for their standing for the right against all criticism. And grateful, too, that we have a Christian man for governor who will defend the Word of God against this so-called science. The Bible tells us that the gates of Hell shall not prevail against the church. Therefore we know there will always be standard-bearers for the cross of Christ. But in these times of materialism I am constrained to thank God deep down in my heart for . every . one whose voice is raised for the uplift of humanity and the coming of God’s kingdom. Mrs. Jesse Sparks Pope, Tennessee Source: Mrs. Jesse Sparks, letter to the editor, Nashville Tennessean, July 3, 1925. Sourcing 1. Why does Mrs. Sparks care about what is taught in schools? Contextualizing 2. To what does Mrs. Sparks refer when she says “these times of materialism”? Close Reading 3. Find all of the words that suggest the presence of a great danger.