Exposing Deliberate Indifference: the Struggle for Social and Environmental Justice in America's Prisons, Jails, and Concentration Camps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

public-Federal ___ structure ___ object Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing (and not yet determined) 110 20 buildings 14 8 sites 47 29 structures 23 7 objects 194 64 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register 0_ Name of related multiple property listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing.) N/A ============================================================================ 6. Function or Use ============================================================================ Historic Functions (Enter categories from instructions) Cat: Government Sub: Correctional Facility Domestic Institutional Housing Industry/Processing Manufacturing Facility Religion Religious Facility Recreation Sports Facility Agriculture/Subsistence Agricultural Field Agriculture/Subsistence Animal Facility Agriculture/Subsistence Agricultural Outbuilding Current Functions (Enter categories from instructions) Cat: Recreation Sub: Sports Facility Vacant/Not in use ============================================================================ 7. Description ============================================================================ Architectural Classification (Enter categories from instructions) Colonial Revival Beaux Arts Bungalow/Craftsman Materials (Enter categories from instructions) foundation brick, concrete roof slate, asbestos, asphalt, metal walls brick, weatherboard, concrete, metal other Narrative Description (Describe the historic and current condition of the property -

To Ask Freedom for Women 1

To Ask Freedom for Women 1 “To Ask Freedom for Women”: The Night of Terror and Public Memory Candi S. Carter Olson Department of Journalism and Communication, Utah State University Author note Candi Carter Olson https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5696-4907 To Ask Freedom for Women 2 On November 14, 1917, 33 suffrage picketers from the National Woman’s Party were sentenced for ostensibly obstructing traffic in front of the White House, where the so-called Silent Sentinels had been protesting President Wilson’s lack of intervention on women’s suffrage. Thirty-one of these women were transferred to Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. In what would become known as the “Night of Terror,” those women were greeted violently by Occoquan Superintendent W.H. Whittaker and around 441 club-wielding prison guards. They were kicked. Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, was widely reported to have had her arms twisted behind her, after which she was slammed over the back of an iron bench multiple times. Lucy Burns, who co-founded the National Woman’s Party (“NWP”) with Alice Paul, was handcuffed to the bars of her cell with her arms over her head. Stories of the Night of Terror were sensational, but contemporary memorialization of the event marked it as turning point in the fight for universal suffrage. Author Louise Bernikow (2004) wrote “For all the pain, this brutal night may have turned the tide…It would take three more years to win the vote, but the courageous women of 1917 had won a new definition of female patriotism” (para. -

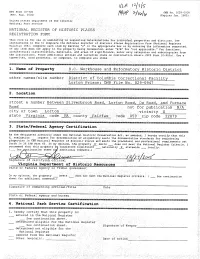

DC Workhouse and Reformatory National Register

D ISTRICT OF C OLUMBIA W ORKHOUSE AND R EFORMATORY National Register Nomination prepared for: County of Fairfax, Department of Planning and Zoning Fairfax, Virginia prepared by: John Milner Associates, Inc. Charlottesville and Alexandria, Virginia September 2005 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form D.C. Workhouse and Reformatory Historic District Fairfax County, Virginia Page 1 ============================================================================ NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires Jan. 2005) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ============================================================================ 1. Name of Property D.C. Workhouse and Reformatory Historic District ============================================================================ -

THE SUFFRAGE PICKETS and FREEDOM of SPEECH DURING WORLD WAR I Catherine J

Working Paper Series Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Year 2008 \We Are At War And You Should Not Bother The President": The Suffrage Pickets and Freedom of Speech During World War I Catherine J. Lanctot Villanova University School of Law, [email protected] This paper is posted at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/wps/art116 “WE ARE AT WAR AND YOU SHOULD NOT BOTHER THE PRESIDENT”: THE SUFFRAGE PICKETS AND FREEDOM OF SPEECH DURING WORLD WAR I Catherine J. Lanctot1 “GOVERNMENTS DERIVE THEIR JUST POWER FROM THE CONSENT OF THE GOVERNED.” – Banner carried by suffrage pickets, July 4, 1917 “You know the times are abnormal now. We are at war, and you should not bother the President.” – Judge Alexander Mullowney, sentencing pickets to jail, July 6, 1917 I. The Story of the 1917 Picketing Campaign. On November 7, 1917, suffrage leader Alice Paul lay quietly in a hospital bed in the jailhouse for the District of Columbia, having refused to eat for more than two days. The thirty- two year old Paul, one of the most notorious women in America, was the chairman of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), a small and militant suffrage offshoot of the mainstream National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Since early January, Paul had orchestrated an unprecedented campaign of picketing the White House as public protest against the failure of the Wilson Administration to support woman suffrage. Over time, the picketing campaign had transformed from a genteel demonstration for the vote into a full-scale legal battle with local police and Administration officials over the right to speak freely and to petition the government. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. HISTORICAL LANDMARKS AND LANDSCAPES19 OF LGBTQ LAW Marc Stein The American historical landscape is filled with sites where people who engaged in same-sex sex and transgressed gender binaries struggled to survive and thrive. In these locations, “sinners,” “deviants,” and “perverts” often viewed law as oppressive. Immigrants, poor people, and people of color who violated sex and gender norms had multiple reasons for seeing law as implicated in the construction and reconstruction of social hierarchies.