Relationships Between Container Terminals and Dry Ports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Importance of the Belgian Ports : Flemish Maritime Ports, Liège Port Complex and the Port of Brussels – Report 2006

Economic importance of the Belgian ports : Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels – Report 2006 Working Paper Document by Saskia Vennix June 2008 No 134 Editorial Director Jan Smets, Member of the Board of Directors of the National Bank of Belgium Statement of purpose: The purpose of these working papers is to promote the circulation of research results (Research Series) and analytical studies (Documents Series) made within the National Bank of Belgium or presented by external economists in seminars, conferences and conventions organised by the Bank. The aim is therefore to provide a platform for discussion. The opinions expressed are strictly those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. Orders For orders and information on subscriptions and reductions: National Bank of Belgium, Documentation - Publications service, boulevard de Berlaimont 14, 1000 Brussels Tel +32 2 221 20 33 - Fax +32 2 21 30 42 The Working Papers are available on the website of the Bank: http://www.nbb.be © National Bank of Belgium, Brussels All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. ISSN: 1375-680X (print) ISSN: 1784-2476 (online) NBB WORKING PAPER No. 134 - JUNE 2008 Abstract This paper is an annual publication issued by the Microeconomic Analysis service of the National Bank of Belgium. The Flemish maritime ports (Antwerp, Ghent, Ostend, Zeebrugge), the Autonomous Port of Liège and the port of Brussels play a major role in their respective regional economies and in the Belgian economy, not only in terms of industrial activity but also as intermodal centres facilitating the commodity flow. -

GREENTECH 2017! - ABC Recycling - Glencore There’S Less Than a Month Left to Green Marine’S Annual Conference, Greentech 2017

MAY 2017 L’INFOLETTREGREEN DE MARINE L’ALLIANCE NEWSLETTER VERTE IN THIS ISSUE New participants: 3,2,1… GREENTECH 2017! - ABC Recycling - Glencore There’s less than a month left to Green Marine’s annual conference, GreenTech 2017. This year’s conference will - Port of Belledune be held at the Hyatt Regency Pier Sixty-Six in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, from May 30th to June 1st. Most of the New supporters: exhibition showroom booths have been sold, the sponsored events await delegates, and registration continues. - Clean Foundation Along with busily preparing for GreenTech 2017, the Green Marine team is compiling the environmental - Port Edward performance results of the program’s participants and putting the final touches to Green Marine Magazine. Both - Prince Rupert the results and the magazine will be unveiled at the conference. - Protected Seas Industry success stories: - Seaspan NEW MEMBERS - Port NOLA - Desgagnés - Port of Hueneme - CSL Group GREEN MARINE PROUDLY WELCOMES THREE NEW - Neptune Terminals Spotlight on partners & supporters PARTICIPANTS - Ocean Networks Canada - Hemmera The Belledune Port Authority was incorporated as a federal not-for-profit commercial port authority on Events March 29, 2000, pursuant to the Canada Marine Act. The Port of Belledune offers modern infrastructure and GreenTech 2017 equipment, including a barge terminal, a roll-on/roll-off terminal and a modular component fabrication facility. The #BragAboutIt Port of Belledune is a year-round, ice-free, deep-water port that offers efficient List of all Green Marine members stevedoring services. The port has ample outdoor terminal storage space and several indoor storage facilities – a definite competitive advantage for bulk, breakbulk and general cargo handling. -

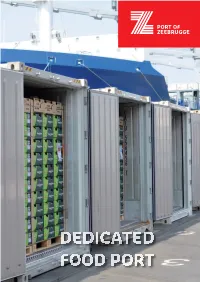

Port of Zeebrugge Is Located in the World’S Most Densely Populated Consumer Area So Your Importing And/Or Exporting Partner Is Never Far Away

DEDICATED FOOD PORT THE F OOD SECTOR Infrastructure Food cargo travels in many ways: in containers or RORO freight loads, in bulk or reefer ships. That’s why multiple installations for the reception, handling and storage of perishables are found in the port area. What’s more, the Port of Zeebrugge is located in the world’s most densely populated consumer area so your importing and/or exporting partner is never far away. CSP reefer C.RO roro P&O roro Pittmann Seafoods Acutra BIP European Food Zeebrugge Food Center (fish) Logsitics Borlix Zeebrugge ECS Breakbulk Terminal 2XL Flanders Cold Center II Flanders Cold Zespri Center I Belgian New Fruit Wharf Tropicana Tameco Seabridge Verhelst-Agri* Voeders Huys* Seaport Shipping & Trading* Group Depré* Oil Tank Terminal* *Agrobulk terminals located in the port of Bruges C ONCEPT Intercontinental food cargo We know that sensitive reefer cargo and frozen food transport and warehousing deserve a dedicated approach. That is why we have brought together all the official authorities involved with perishable cargo in our Border Control Post (BCP). In this specialised centre, veterinary clearance, customs and maritime police all work under the same roof to speed up the clearance of your cargo, which is completely segregated from other food cargo to avoid contamination with products. In the Port of Zeebrugge, your container can be dispatched to the market while the vessel is at berth; the food cargo can make its way to your customers or be temporarily stored in our deepfreeze warehouses. ContinentalContinental Europe Europe & & UK UK cargo cargo Food cargo originating from the EU travels freely within the unified European market. -

To: Mayor and Council City of Delta COUNCIL REPORT Regular

City of Delta COUNCIL REPORT F.06 Regular Meeting To: Mayor and Council File No. : 1160-01 From : Engineering Department Date: August 01, 2018 World Conference on Cities and Ports Delegation Report The following report has been reviewed and endorsed by the Acting City Manager. • RECOMMENDATION: THAT this report be received for information. • PURPOSE: The purpose of this report is to provide information on Delta's delegation to the 16th World Conference on Cities and Ports in Quebec City. • BACKGROUND: At the invitation of the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, the City of Delta sent a delegation to the 16th World Conference on Cities and Ports in Quebec City June 11-14, 2018, organized by AIVP and Port Quebec. AIVP is a France-based international non profit association that was established in 1988 with the main objective of improving dialogue between cities, ports, and their partners. The conference brought together policy makers, business professionals, and academics from around the world to explore the challenges facing port cities and solutions to those challenges adopted by successful port cities with a focus on sustainability. Delta's delegation included Mayor Lois E. Jackson; Steven Lan, Acting City Manager; and Paul Scholfield, Fire Chief and had been pre-approved by Council at the May 14 Regular Meeting. The Port of Vancouver delegation was led by Robin Silvester, President and CEO and Eugene Kwan, Vice Chair, Port of Vancouver Board of Directors. • DISCUSSION: Conference Summary The focus of Delta's delegation to the conference was to engage in dialogue about the port-city interface in other jurisdictions, review best practices from other parts of the world, and develop ideas for potential improvements in Delta. -

Annual Report 2012-Soaring to New Heights.Pdf

Administration portuaire de Québec Direction générale / Communications et relations publiques 150, rue Dalhousie, C.P. 80, Succursale Haute-Ville Québec (Québec) G1R 4M8 Canada Tél.: 418 648-3640 Fax: 418 648-4160 [email protected] www.portquebec.ca www.marinaportquebec.ca www.espacesdalhousie.com Design graphique : safran.ca SOARING TO NEW HEIGHTS 2012 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE QUÉBEC PORT AUTHORITY The mission of the Québec Port Authority (QPA) is to encourage and develop maritime trade, to serve the economic interests of the Québec region and Canada, and to ensure its profitability while respecting the community and the environment. The Québec Port Authority is a financially autonomous shared governance organization constituted under the Canada Marine Act to effectively manage all assets in its purview. The QPA oversees a section of the river measuring 35 square kilometers, and nearly 210 hectares of developed port land. 2012 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE QUÉBEC PORT AUTHORITY Photo courtesy: Louis Rhéaume, pilot for CLSLP CONTENTS 4 The Port of Québec by numbers 4 Handled tonnage 5 Cruises 5 Investments 5 Jobs creation 5 Events 7 A word from the Chairman of the Board 11 A word from the President and CEO 15 The Port of Québec, a gateway to the World 16 Maritime trade routes at a glance 19 A Favourite Port of Call for Cruise Passengers 19 Unprecedented passenger traffic 20 A port like no other 20 Casting its seductive charm 23 A One-of-a-kind Urban Space 23 A marina in the heart of town 24 The unique espaces dalhousie 26 Major event partners -

US Fabrication for Konecranes Rmgs APMT to Monetise Facilities

FEBRUARY 2018 US fabrication for Konecranes RMGs The steel structures for the and trolley, plus the spreader and The drives and controls for cranes), and multiple US ports eight new Konecranes widespan headblock. The gantry structures the GPA RMGs will be supplied for mobile harbour cranes. Im- RMGs ordered by the Georgia are not, however, included in by TMEIC, which is headquar- portantly, there is no blanket Ports Authority (GPA) for its the waiver, and Konecranes con- tered in Roanoke (VA), and is a waiver for container cranes as a Mason Mega Rail project will be firmed that these will be manu- wholly owned subsidiary of Ja- class, and a separate waiver must fabricated in the USA. factured in the US, but declined pan’s Toshiba Mitsubishi-Electric be sought for each purchase that The Mason Mega Rail project to name the fabricator at this stage. Industrial Systems Corporation. uses any federal grant, for the full received a US$44M grant from The RMGs are very large, TMEIC is also supplying drives price or part of it. the US Government’s FAST- with a span of 53.34m, and to the GPA for new and retrofit The question of whether to LANE programme. This funding 16.7m cantilevers. Capacity is STS cranes, and the RMG drives fabricate RMGs in the US will is subject to a ‘Buy America’ re- 40t, and lifting height is 11m. will have many common parts. come up every time. In the cur- quirement that stipulates a “do- WorldCargo News believes that The decision to use a US fab- rent political climate, where the Fully erect delivery of new cranes has become a familiar site in Savannah, but mestic manufacturing process” these will be the biggest contain- ricator sets an important prece- Trump administration is trying structures for the port’s eight new RMGs will be fabricated in the USA for the steel and iron products. -

Economic Importance of the Belgian Ports: Flemish Maritime Ports, Liège Port Complex and the Port of Brussels – Report 2012

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mathys, Claude Working Paper Economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels – Report 2012 NBB Working Paper, No. 260 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: Mathys, Claude (2014) : Economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels – Report 2012, NBB Working Paper, No. 260, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/144472 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die -

4ALLPORTS News Update March 2020

4ALLPORTS News Update March 2020 UNCTAD warns of $2 trillion shortfall following COVID-19 News in brief: would mark the end of countries (excluding Gothenburg continues rail investment: Gothenburg has the growth phase of China). The most badly announced plans for continued this cycle cannot be affected economies in expansion of the Gothenburg ruled out. this scenario will be oil Port Line, one of Sweden’s -exporting countries, most important railway links. The almost 10 km line is today a “Back in September we but also other com- single-track line with too low of were anxiously scan- modity exporters, a standard to meet future ning the horizon for which stand to lose traffic needs. An expansion of possible shocks given more than one per- the Port Line to double-track is required to increase both the the financial fragilities centage point of amount of rail traffic and the left unaddressed since growth, as well as total amount of freight traffic. the 2008 crisis and the those with strong Recently, construction of the persistent weakness in trade linkages to the final stage began, which is the The spread of the coro- signs of spreading con- 1.9-kilometer-long stretch demand,” said Richard initially shocked econ- navirus is a significant tagion, the analysis between Eriksberg and Pölsebo. Kozul-Wright, omies. economic threat accord- says. The new section opens for UNCTAD’s director of traffic in 2023. ing to United Nations globalization and de- According to UNCTAD, Conference on Trade However, a combina- Port of Hull deploys electric velopment strate- growth decelerations and Development tion of asset price de- forklifts: A fleet of six, electric gies. -

The Economic Importance of the Belgian Ports: Flemish Maritime Ports, Liège Port Complex and the Port of Brussels – Report 2016

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Coppens, François; Mathys, Claude; Merckx, Jean-Pierre; Ringoot, Pascal; Van Kerckhoven, Marc Working Paper The economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels – Report 2016 NBB Working Paper, No. 342 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: Coppens, François; Mathys, Claude; Merckx, Jean-Pierre; Ringoot, Pascal; Van Kerckhoven, Marc (2018) : The economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels – Report 2016, NBB Working Paper, No. 342, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182219 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

DEDICATED AGRIBULK PORT a GRIBULK & L O G I S T I C

DEDICATED AGRIBULK PORT A GRIBULK & LOGISTIC Terminals Shipping companies / Brokers Actors in the port ZIP reefer APMT reefer C.RO roro P&O roro Pittmann Seafoods Acutra BIP European Food Zeebrugge Food Center (fi sh) Logsitics Borlix Zeebrugge ECS Breakbulk Terminal Flanders Cold Center II 2XL Zespri Tropicana Belgian New Fruit Wharf Flanders Cold Center Tameco Seabridge Seaport Shipping & Trading* Group Depré* Oil Tank Terminal* *Agrobulk terminals located in the port of Bruges W HY P ort O F Z eebrugge Strategically located at the crossroads of cargo flows between the continent and the U.K., Scandinavia and Southern Europe Intercontinental bulk & container shipping services A port with full nautical accessibility and excellent hinterland connections by road, rail and barge Dedicated infrastructure for dry & liquid agribulk products Strong tradition & unique knowhow in the storage, handling, distribution, freight forwarding and final delivery of agribulk cargo Value added activities e.g. toasting & extruding, de-hulling, bagging, sieving, mixing, etc. Reaching over 60% of E.U. buying power within a 550 km. range Tailor-made distribution & investment options M arket S coV ered / S H ort S ea SHORTSEA RORO LINES Cobelfret / CldN DFDS Seaways EML Finnlines Flota Suardiaz KESS / K-Line P&O Ferries SOL Toyofuji UECC SHORTSEA LOLO LINES CMA CGM Containerships DFDS Container Line SCS Multiport CLDN Portconnect Port Authority Zeebrugge | MBZ Isabellalaan 1 B-8380 Zeebrugge/Belgium T +32 (0)50 54 32 11 F +32 (0)50 54 32 24 www.portofzeebrugge.be [email protected] M ARKETS COVERED / I NTERCONTINENTAL Shipping lines C ONTACT US We are glad to point you towards the best possible transport solutions for your needs or offer professional support in setting up your value-added logistics operations. -

Treasure Committee – Oral Evidence Session – the UK’S Economic Relationship with the European Union

House of Commons – Treasure Committee – Oral Evidence Session – The UK’s economic relationship with the European Union 5th of June 2018 Joachim Coens, President-CEO The port of Zeebrugge Historic link UK – Bruges Now: intermodal hub and gateway for the EU market Zeebrugge bridgehead for the U.K. distribution P&O PSA Top 5 shipping C.Ro companies Zeebrugge – UK: ICO WWL ICO C.Ro ICO TOYOTA ICO Kemi Oulu UK is our main trade partner. We provide Finland tailormade solutions for all traffic to UK. Rauma Uusikaupunki Kotka St.Petersburg Totaal UK 2017: Helsinki Hanko 17.174.003 ton Sweden Ust Luga Thames area: 8.874.119 ton Bergen Norway Paldiski Humber area: 5.596.801 ton OSLO Tees area: 1.751.647 ton Drammen Moss Scotland: 635.119 ton Larvik Estonia Langesund Halden Russia Others: 316.317 ton Stavanger Kristiansand Wallhalm Göteborg Hirtshals Rosyth Den. Teesport Middlesbrough Esbjerg Malmö Hull Killingholme Immingham Gdynia Dublin Eire Grimbsy 46%Cuxhaven or 17.2 million tonnes in 2017 U.K. Emden Bremerhaven Mostly containers and RoRo Amsterdam Pologne Tilbury traffic Portbury Sheerness Neth. Purfleet Rotterdam Southampton 67% export, 33% import ZEEBRLorUemG ipsumGE EmploymentGermany : 5.000 jobs directly linked to UK traffic Belgium Added value: 500 million Le Havre EUR per year directlyCzech linked Rep. to UK traffic France Italy Vigo Livorno Santander Bilbao Pasajes Sète Leixoes Derince Borusan Barcelona Spain Yenikoy Portugal Tarragona Greece Turkey Sagunto Valencia Gioia Tauro Piraeus Malaga Tenerife Las Palmas Tanger Casablanca Mostaganem Tailormade solutions: 69 services a week Zeebrugge bridgehead for the U.K. distribution Day B : Day A : 24 hours 14.00 hrs: ‘order picking’ Delivery in the U.K. -

Port of Antwerp-Bruges Structure Port of Antwerp-Bruges Is a Limited

Port of Antwerp-Bruges Structure History Port of Antwerp-Bruges is a limited liability company under public law, in Early 2018 Start of discussions between the which the City of Antwerp and the City of Bruges are the sole shareholders. City of Antwerp and the City of Bruges with a view to closer Ownership of the shares is distributed as follows: collaboration City of Antwerp: 80.2% June 2018 Economic complementarity and robustness study City of Bruges: 19.8% Registered office: Zaha Hadidplein 1, B-2030 Antwerp December 2019 Start of negotiations Organisation 12 February Signature of the two-city 2021 agreement between the Board of directors municipal executives of Antwerp and Bruges . Chair: Annick De Ridder . Vice-chair: Dirk De fauw March 2021 Under approval of the municipal . City of Bruges: 3 representatives, including vice-chair Dirk De fauw councils of Antwerp and Bruges, . City of Antwerp: 6 representatives, including chair Annick De Ridder after which the proposal will be . Independent members: 4 representatives referred to the competition authorities Executive Committee Launch of integration process . Nominated CEO: Jacques Vandermeiren The transaction is subject to a number of customary suspensory conditions, including the need to obtain approval from the Belgian competition authorities. Both parties will endeavour to complete the transaction during the course of 2021. A world port ... By joining forces, the ports of Antwerp and Zeebrugge will strengthen their position within the global logistical chain. Port of Antwerp Port